Et in Utah Erant: The Reel Works of J.G. Ballard, Tacita Dean, and Robert Smithson

by Rachel Valinsky

Tacita Dean, JG, 2013. Anamorphic 35mm film, color and black and white, optical sound. 26 1/2 min. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris, and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Everything about movies and moviemaking is archaic and crude. One is transported by this Archeozoic medium into the earliest known geological eras. The movieola becomes a “time machine” that transforms trucks into dinosaurs.1

At the end of film and at the beginning of film and at the heart of film is Tacita Dean. A pioneer of the medium at the time of its projected extinction by the accelerating rise of the digital, Dean maintains an artistic practice deeply rooted in film and its specificities. Her most recent work, JG, commissioned by the Arcadia University Art Gallery in Glenside, Pennsylvania, and recently exhibited at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, is a 26-1/2 minute, 35mm film named after the iconic science fiction writer J.G. Ballard and taking as its subject Robert Smithson’s monumental earthwork, Spiral Jetty (1970).

The story of this unusual triad of influences and interests begins in 1997 at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. Having heard that Smithson’s Jetty had risen above water levels after a long period of submersion in the Great Salt Lake, Dean went looking for the elusive earthwork, following vague directions faxed to her by the Utah Arts Council. She didn’t find the earthwork, but the effort resulted in a 27-minute-long sound piece, Trying to Find the Spiral Jetty, recorded after the fact and reconstructed from memory and verbal reports.

Following this failed attempt at finding the Jetty, and prompted by an enduring correspondence with Ballard about their shared interest in Smithson, Dean returned to Utah in the fall of 2009 for the first of two trips during which JG was filmed. She had grown fascinated by the resonances between the artist’s spiral earthwork and Ballard’s short story “The Voices of Time” (1960), particularly when she discovered that Smithson owned the book and had likely read it before creating his iconic spiral.

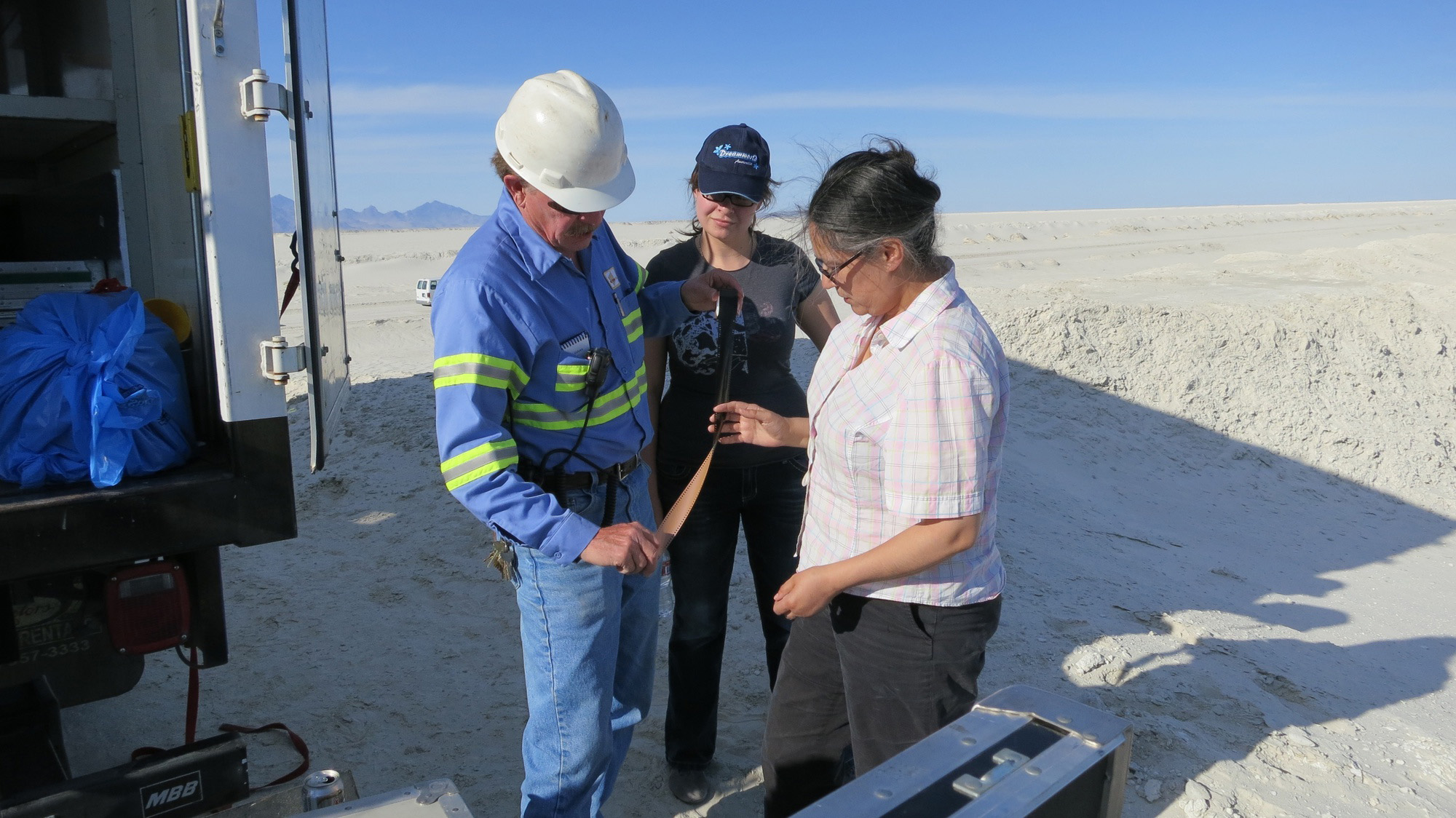

Tacita Dean on location for JG at Intrepid Potash, Wendover, Utah, with Ponds Supervisor, Russ Draper, and his daughter, Jessica (May 2012). Photo: Richard Torchia.

Her film postulates a possible response to a challenge Ballard posed to her in one of their last exchanges: to “treat [Spiral Jetty] as a mystery that your film will solve.”2 By 2012, Dean had shot in six locations across Utah and California, from the arid Death Valley desert—the driest place in North America—to the brine basin and tufa formations of Mono Lake, the red pool at Rozel Point (home to Jetty), the vast expanse of the Great Salt Lake, and the white salt flats of Wendover and its Intrepid Potash facility.

The film’s locations are interwoven through a technique developed and patented by the artist in collaboration with the architect Michael Bölling and first employed for her 2011 Turbine Hall commission, FILM, at Tate Modern. This remarkable new process, called aperture gate masking, employs 3-D printed stencils of various shapes—for the most part, elementary geometrical forms—placed inside the camera, directly onto the aperture gate. The film is thus made inside the camera: The filmstrip is exposed, rewound, and re-exposed, building into the single frame (or frames) a layering of spirals, circular openings, rectangles, and other shapes.3

Within this highly controlled and precise process is the constant risk of failure and error inherent in the blind operation—the inevitable risk of loss, the irrecoverability of film that has been ruined, and the impossibility of returning to the site—but also always the quality of the chance operation, the happening upon the unexpected that can only be discovered once the work has been done.4 It is precisely this tension that is at play in aperture gate masking, recalling the origins of celluloid film while expanding the medium’s potential at the very moment “when it is facing its apocalypse.”5

Tacita Dean, JG, 2013. Anamorphic 35mm film, color and black and white, optical sound. 26 1/2 min. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris, and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Ballard’s short story relates to Smithson’s Jetty at a very basic level through the motif of the spiral ideogram. The mandala figure brackets the story, which opens with the discovery of what appears to be “a huge solar disc, with four radiating diamond-shaped arms, a crude Jungian mandala,” carved into the floor of a rectangular pool, and ends in the construction of a monumental mandala made of concrete.6Ballard’s protagonist, Powers, is a retired scientist following in the footsteps of his predecessor, Whitby, a cryptic figure who spent the last days of his life in an apparent stupor, ritualistically making the pool carvings discovered at the outset of the story. After Whitby’s suicide, Powers maintains his colleague’s laboratory and continues his experiments with an irradiation machine called the Maxitron. The machine’s high radiation levels cause a “silent pair” of otherwise dormant, or inactive, genes to be activated in exposed organisms—various animal species and vegetation that subsequently undergo bizarre mutations and develop highly specialized sensory organs that seem to sense time and adapt their metabolisms to geological conditions and radiological climates. The Sleepers, an ever-growing subset of the population afflicted by a permanent slumber from which they cannot rise, all possess this “silent pair.” Both phenomena—animal and vegetable mutation and terminal human sleep—are closely linked, although the consequences of the as-yet-untested irradiation on humans possessing this set of special genes remains unclear.

By the end of the story, it emerges that Powers has been at work on the construction of a giant concrete mandala, a re-creation of Whitby’s ideogram. It’s implied that Powers—whose hours of wakefulness diminish increasingly each day—may have exposed himself to Maxitron irradiation, for when he pays his last visit to the concrete mandala, he seems to have developed a form of cosmic hearing. “He saw the dim red disc of Sirius, heard its ancient voice, untold millions of years, dwarfed by the huge spiral nebulae in Andromeda, a gigantic carousel of vanished universes, their voices almost as old as the cosmos itself.”7 As he approaches the center of the mandala, the tumult of the sounds becomes focused—he hears the archaic voices of the constellations across all times. Ballard describes time as a current originating in the cosmos, moving steadily toward Powers, and finally sweeping him away at the moment of his death. In that moment, as Powers gives himself to the current, all the surrounding landscape fades and his body slowly dissolves into the continuum, yet his eyes remain peeled on the mandala. Inscribing itself as retinal afterimage of a special sort, the spiral becomes a visual fixture: the image of a cosmic clock.

“The time in film is the time of time itself.”8

This cosmic swoop, the oceanic feeling of being engulfed by time, is precisely what Smithson recounts having experienced in his first encounter with the site of Spiral Jetty. He was drawn to Rozel Point because of its tomato-soup color, the water’s deep wine red caused by the algae in the brine. In his 1972 essay on Spiral Jetty, Smithson writes:

“As I looked at the site, it reverberated out to the horizons only to suggest an immobile cyclone while flickering light made the entire landscape appear to quake. A dormant earthquake spread into the fluttering stillness, into a spinning sensation without movement. This site was a rotary that enclosed itself in an immense roundness…The shore of the lake became the edge of the sun, a boiling curve, an explosion rising into fiery prominence. Matter collapsing into the lake mirrored the shape of a spiral…One seizes the spiral, and the spiral becomes a seizure.”9

Smithson’s allegorical recounting of this vision emphasizes the role of the artist as “site-seer.” It is his discovery of the site itself that engenders the eruption of its potentialities; it shatters before him into cracks and gaps from which meaning arises. Dashing backward into the future, Jetty exists as a striking cinematic vision before it acquires its sculptural form: Flickering light brings the site into chaotic focus, and the stillness of the landscape is wildly disturbed by a spinning sensation, like the spiraling of film on its reel that animates the still.

Spiral Jetty ultimately takes many forms: as an earthwork, a text, a series of photographs, and a film. Smithson’s film—a highly influential, experimental artwork in its own right—opens with an anamorphic sun expanding and exploding outward into blurry, fiery blasts. Transitional markers, where Smithson films a dirt road, first looking forward to the path ahead, and subsequently from the back of the car, looking at the dust-filled trail caused by the vehicle as he drives to and from the site of Jetty in Utah, occur in the film at five points. This continuous, placeless road going nowhere and coming from nowhere makes it clear that the film seeks to situate itself in a kind of lost or splintered world made of many places.

Smithson’s lost world is merged with the paleontological, where time is not experienced horizontally—like a road—but vertically, as layered, stratospheric phenomena. Attempting to find the location of Spiral Jetty, he consults maps of the geography of the Jurassic period. In one scene, shot at the Great Notch Quarry in New Jersey, Smithson’s wife, the artist Nancy Holt, is filmed throwing ripped-out pages of a book down a hill. As they amass on the caked and crackly surface of the ground, a voice-over announces, “The earth’s story seems at times like a story recorded in a book, each page of which is torn into small pieces. Many of the pages and some of the pieces of each page are missing.”10 In another scene, four books are stacked atop a mirrored surface—their spines read The Lost World, Mazes & Labyrinths, Sedimentation, and The Day of Dinosaurs. The Lost World alone does not find its reflection in the mirror.

As the film shifts to the desert land of Utah, Spiral Jetty causes the landscape of undifferentiated, barren sameness—in which nothing seems to have ever changed—to become radically altered. This is clear at once when shots of the slowly undulating red and pink currents of the waters at Rozel Point are supplanted in at least three instances by violent close-ups of front loaders, like technological dinosaurs—spasmodically dumping black basalt and limestone from the shore into the lake to form a spiral. Seen through sunburnt eyes, both sky and sea at Rozel Point are saturated with crimson hues: The spiral brings life to the site, the briny currents circulating like blood through veins.

Tacita Dean, JG, 2013. Anamorphic 35mm film, color and black and white, optical sound. 26 1/2 min. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris, and Frith Street Gallery, London.

“A film is a spiral made up of frames.“11

At the moment of the film’s focus on Jetty, we approach Dean’s film; for indeed, her work revolves around this same landscape and is certainly looking to Smithson’s film in the process.

A male voice in JG tells us that Spiral Jetty “literally sees time.” The voice-over text, provided by British actor Jim Broadbent, reads excerpts from Ballard’s letters to Dean, the short stories “The Voices of Time” and “Prisoner of the Coral Deep,” and his 1997 essay “Robert Smithson as Cargo Cultist,” written for an exhibition catalog published by Williamsburg, Brooklyn–based gallery Pierogi 2000, on the occasion of a show in which Smithson’s Dead Tree was posthumously installed. Appearing intermittently throughout the film, the voice-over provides a continuous reminder of the parallels between Dean’s film and Smithson’s earthwork. Paraphrasing a question posed in Ballard’s essay, the voice asks what kind of “cargo might have birthed the Spiral Jetty,” that “labyrinth designed in the guise of a cargo terminal”; and Dean’s film opens nearly as a response to his question.12

A white, psychedelic sun emanating yellow rays in all directions, embedded in a deep orange background, casts its reflection below. This happens within the confines of a gigantic trapezoid, one of Dean’s aperture gate masks. The effect is chilling: The reflection becomes a solar double, a cool counterpart marked by its saline whiteness. It is a giant landing dock, quickly succeeded by a shot of Jetty, itself (or rather, another mask in its spiraling shape), red with fire, overtaken by the sun. The succession of images creates a likeness between the sun and the Jetty, positioning the Jetty, as a receptor of solar rays (a cargo terminal) but also as a landlocked likeness of the sun above.

In his film, Smithson presents a map of northwestern Utah showing the Great Salt Lake and its ancient predecessor, Lake Bonneville, which he explains in his voice-over was believed to connect to the Pacific Ocean by way of a subterranean channel. This ancient local lore, held through the 1870s, claimed the head of this channel—the site of the Jetty,—as the location of a mythological whirlpool lodged in the lake’s center, a vortex infinitely spiraling downward to the core of the earth. In geological terms: the beginning of time. Its positive mirror, then, is none other than Ballard’s mandala, reaching up and out into the infinities of cosmic time.

Dean’s and Smithson’s films hover around these two temporal poles, bringing them closer together than could be imagined. Both films radically engage with the shift from the still to the moving image and address the spatiotemporal gap that hangs at the interstice of the two as cosmic, geological, or historic phenomena. They also present the possibility of the equivalence of present and future, adopting Smithson’s notion that “the future doesn’t exist, or if it does, it is the obsolete in reverse. The future is always going backwards.”13

Tacita Dean, JG, 2013. Anamorphic 35mm film, color and black and white, optical sound. 26 1/2 min. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris, and Frith Street Gallery, London.

Exposing and expanding on what film is capable of, even as celluloid faces extinction, is one of Dean’s enduring preoccupations, both in the use of the medium and in the content of her work.14 There is a form of awe apparent here—a psychic life within the landscapes, an ecstatic quality that recurs in the slowness of her investigation, the pristine landscapes, the beauty of the site. It is an ecstasy of rediscovery that film uniquely allows. A lonely armadillo crawling out of itself, furrowing into the earth after emerging from its own shell, is treated with the same curiosity and interest as crystalline salt growth. Vibrantly colored stills alternate with deep black-and-white chiaroscuros, which model the rocky reliefs in the terrain, exposing the intricate details of rocks and stones through light and shadow in a way that anamorphic film is most adeptly suited to do.

Dean’s attunement to the particularities of the medium does not denote an entirely nostalgic approach. Rather, she is committed to film that is of and in the present, albeit with keen foresight of its looming obsolescence. The level of precision involved in her work is, in part, a slowing down of film, a rejection of the ease and speed of digital postproduction, and the distortion of proportions enabled by the digital.15 Dean’s technique is painstaking and meticulous; her process unfolds as the film unfolds, takes the time that film takes.

In “Robert Smithson as Cargo Cultist,” Ballard concludes that “the cargo was a clock, though one of a very special kind.”16 As the imagined cargo landing, then, Smithson’s Spiral Jetty provides a kind of harbor for time—a monumental berth that enables an understanding of time that the stillness and sameness of the Utah desert would otherwise preclude.

For Dean, this is the activity of film: bringing sound and motion to what has been seen and remembered as a silent image. Just as Smithson ends his film with a shot of the film editor’s table, where film is spliced and assembled and above which hangs a photograph of Spiral Jetty, Dean calls attention to the materiality of her film by interspersing single frames with triptychs throughout, using an Ektachrome sprocket hole mask as a framing device that visually transforms the film into a projected filmstrip.

Tacita Dean, JG, 2013. Anamorphic 35mm film, color and black and white, optical sound. 26 1/2 min. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris, and Frith Street Gallery, London.

For both artists, working more than 40 years apart, the filmmaker still has a visionary and near-scientific role, or, as Smithson put it, “the movie editor, [who] over such a chaos of ‘takes’ resembles a paleontologist sorting out glimpses of a world not yet together, a land that has yet to come to completion, the span of time unfinished, a spaceless limbo on some spiral reels.”17For her own part, Dean includes a shot of Ballard’s camera—given to her by the writer’s partner after his death—both as a form of commemoration and a reminder that film begins with the still photograph before it is brought to loop, spiral, and uncoil in time. As Ballard himself wrote, “If only one could unwind this spiral it would probably play back to us a picture of every landscape it’s ever seen.” 18