New Music for a New Age: Return to Nature!

by Adam Overton

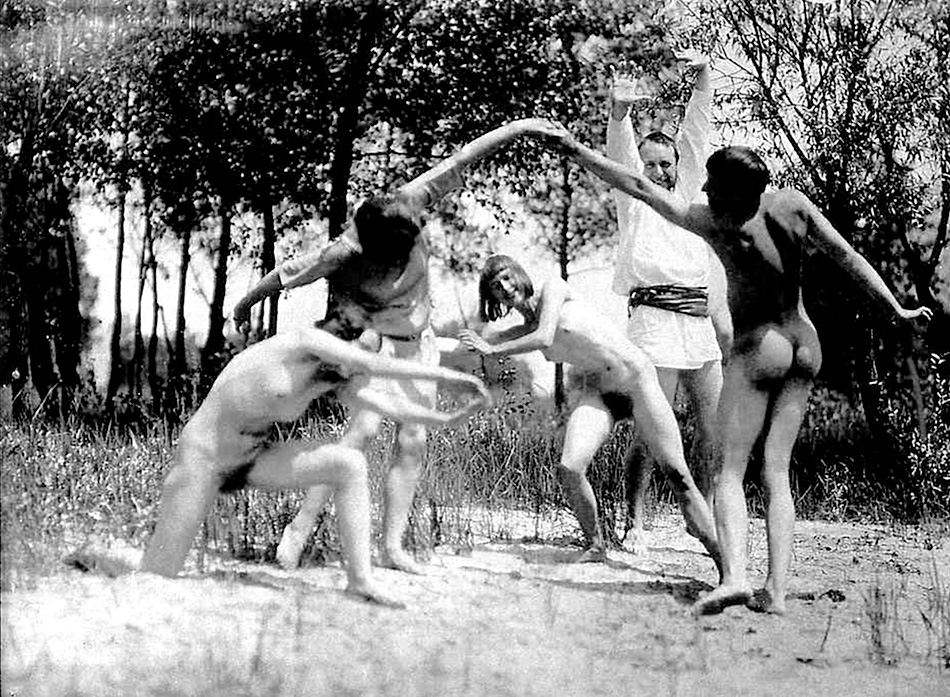

German choreographer Rudolf Laban and his dancers at Monte Verità in Ascona, Switzerland, 1914. Photo: Johann Adam Meisenbach.

With one foot planted squarely in new music and the other in avant-garde spirituality, Eden Ahbez, Anton Szandor LaVey, and Pauline Oliveros represent a motley survey of mystical-musical experimentation over the last century. Although such crossover isn’t unheard of, these three—the Nature Boy, the founder of the Church of Satan, and the founder of Deep Listening, respectively—in spite of their radically differing demeanors and manifestos, all share a remarkable affinity in their anxious plea for a return to nature. What follows is a glance at their music and their doctrines as seen from their distinct vantages.1

eden ahbez, the Voice of Nature

Men who no longer listen to the voice of nature become the victims of a thousand different diseases and miseries. But the creatures of pure nature, on the other hand, the animals of our forests, are free from sickness and from everything else as well that corresponds to the sins and vices of mankind.

—Adolf Just, Return to Nature! (1896)2

As the Industrial Revolution dramatically transformed the quality of life in 19th-century Germany, a lebensreform (life reform) movement responded to the newly polluted urban environment by looking to nature for solutions. There was an explosion of literature hyping topics like vegetarianism, raw foodism, nudism, and water therapy, to name but a few, as an increasingly anxious middle class began to experiment with lifestyle modification and “nature cures” to allay their fears and cure their ills. Countryside sanitariums were established to provide the ill access to fresh air, and a young wandering backpacking movement, the Wandervogel, fashioned a need for Germany’s first network of youth hostels. Some nature-cure advocates like Adolf Just promoted missions into the wilderness as a way to return to Eden and suggested that by simply listening to nature, one could hear the voice of God.3

Though many of these nature cures might today seem quite usual and secular, leaders of this lifestyle revolution, like vegetarian preacher Eduard Baltzer, ultimately promoted their platform as an avant-garde proposal for spiritual revolution.4While lebensreform crept closer and closer to a full embrace of Germanic neopaganism, its call to embrace nature had its roots in evangelical Protestantism and focused on two primary objectives: personal lifestyle transformation as a form of spiritual development and an imperative to reach out and proselytize in order to bring the rest of society along.5

The oft-bearded, long-haired, wandering Naturemenschen (later known as the Nature Boys in the U.S.) were the most radical epitome of this ascetic movement and represented a young, esoteric drop-out culture predating the American hippies by more than half a century. In their pursuit of pure body, mind, and spirit, they criss-crossed their homeland, spreading their message along the way. They were popularized in the first decades of the 1900s by supporters like author Hermann Hesse, who sweetened their lonely mission with the validating tenets of Eastern philosophy.6Soon, a second generation of these German Nature Boy expatriates arrived in the U.S., eventually wandering to the West Coast to settle in Los Angeles, the Santa Monica Mountains, and the nearby desert oasis of Palm Springs.

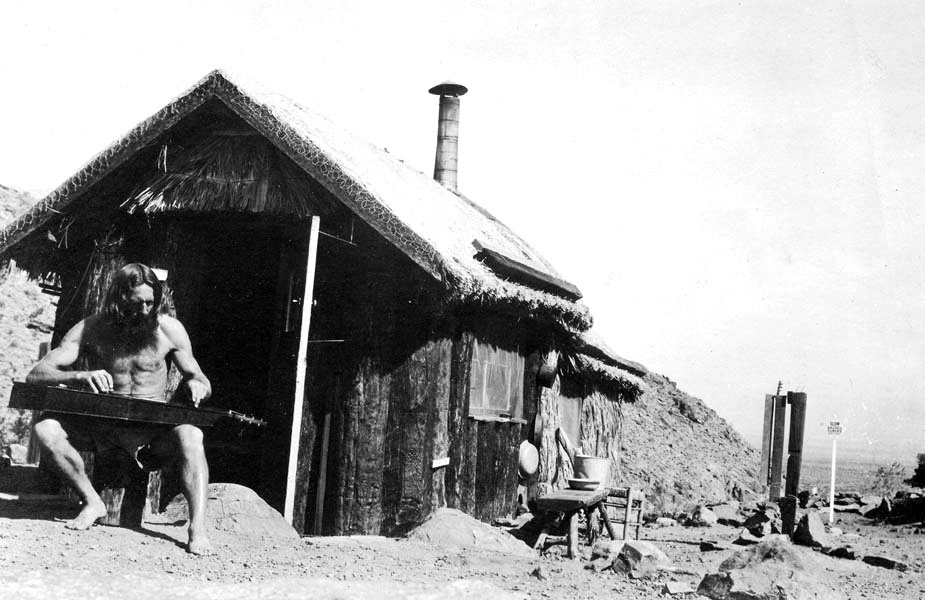

Stephen H. Willard, Bill Pester with his Guitar, ca. 1917. Gelatin silver print. Collection Palm Springs Art Museum.

In the early 1940s, American composer eden ahbez (1908–95) left his Midwestern life behind to become a third-generation Nature Boy, camping in the Hollywood Hills with his wife and child.7 A student of the nature cure, yoga, and the Naturemenschen who had come before him and sporting a Jesus beard and flowing hair, ahbez took the U.S. by storm in 1948, when Nat King Cole made his presumably autobiographical tune, “Nature Boy,” an instant hit.8 Within weeks, ahbez’s eccentric lifestyle was celebrated in Time, Newsweek, Life, and Boys’ Life, reaching into imaginations across America.9

There was a boy / A very strange enchanted boy

They say he wandered very far, very far / Over land and sea

A little shy / And sad of eye

But very wise / Was he

And then one day / A magic day he passed my way

And while we spoke of many things, fools and kings

This he said to me:

“The greatest thing / You’ll ever learn

Is just to love / And be loved in return”

The song featured an extremely exotic blend of influences for this pivotal post-war time: It was written by a messiah-like white man from the wilderness; it had a noticeably “Jewish-sounding” melody (allegedly lifted from a Yiddish composer who later successfully sued ahbez); and it was popularized by Cole, the first crossover African-American crooner.10While reinforcing a baby boom–era celebration of romantic love, ahbez’s vague lyrics also suggest he was preaching something much broader: the radical inclusive love of Christianity’s two-part great commandment to love God and thy neighbor, the latter of which would become central to the hippie and New Age movements. Cole’s adoption of the song is also telling, in that it positioned him as an equally exotic nature “boy”—a pre–Civil Rights era messenger extending the call for brotherly love.

With this success, ahbez quickly became a popular writer of a handful of love songs for a handful of other pop crooners like Sam Cooke and Herb Jeffries.11Although most of his music has since faded into obscurity, one can still find instrumental jazz renditions of “Nature Boy” by John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and dozens of others, and even a more recent version by David Bowie, which was the theme for the 2001 movie Moulin Rouge.12

Less well known, however, is ahbez’s 1960 concept album, Eden’s Island, which presents a much deeper glimpse into ahbez’s loving universe. Featuring his wooden flute and his beatnik poetry and singing, it honors the self-contented “thrill of loneliness” of the barefoot wanderer and a quiet life of fresh fruit, surfing, and meditation on the beach of his private, existential island. And yet despite these monastic vows, ahbez speaks glowingly of a love that fuels him and the other untroubled, fresh-aired island dwellers:

And in the evening

(When the sky is on fire)

Heaven and earth become my great open cathedral

Where all men are brothers

Where all things are bound by law

And crowned with love

Poor, alone and happy

I walk by the surf and make a fire on the beach

And as darkness covers the face of the deep

Lie down in the wild grass

And dream the dream that the dreamers dream

—eden ahbez, from “Full Moon,” on Eden’s Island13

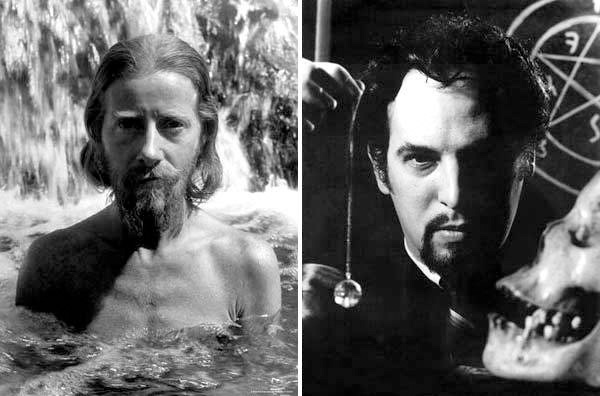

Left: Nature Boy eden ahbez, ca. 1945. Peter Stackpole Archive/Gift of the Stackpole Family © Peter Stackpole. Right: Anton Szandor LaVey, ca. 1960s.

Anton Szandor LaVey and the Satanic Music of the Jungle

Brother Satan I call forth this night, all of your forces, attain me…and the elevation…of the superior human animal. We are superior, and we are superior not by ethnic means, but by the superior force of the will, the imagination, the creativity, and the very essence of resourcefulness, and survival, that is the heart and the very soul of the Satanist.

—Anton Szandor LaVey, Invocation to Satan14

Although the Church of Satan was founded in San Francisco in April 1966, The Satanic Bible suggests that the groundwork was laid in the 1940s, when a 16-year-old Anton Szandor LaVey (1930–97) began working as a carnival organist.15The impressionable young musician was titillated as he played for both the Saturday-night striptease acts and the Sunday-morning tent-show evangelists, which often shared the same audience of “sinners.” 16

It was partly this desire to provide the giggling, licentious soundtrack to sensuality, sin, and the hypocritical dance of righteousness that buoyed the mischievous charter of the Church of Satan and the ascendance of LaVey as its Black Pope. Satanism embraces a disobedient, live-and-let-die attitude with roots in social Darwinism and the objectivism of Ayn Rand but with a greater interest in ceremonial witchcraft and the plundering of religious artifice.17By turning away from the unrealistic strictures of religion and “relearn[ing] the Law of the Jungle,” the satanist can become king/god of his own self-centered, materialist realm and indulge fully in “physical, mental, [and] emotional gratification.”18As a religious philosophy, LaVeyan satanism is ultimately a roaring attack against the Abrahamic quest to repress humanity’s natural urges.

Oddly enough, satanism shares a fundamental concern with the various avant-garde essence faiths that were beginning to gain traction in the 1960s and ’70s in nearby spiritual marketplaces like Esalen. These faiths emphasized a divinity to be found within the individual and sought to harness vast stores of human potential in order to help evolve humankind and effect change in the world.19According to most of these faiths, setting such transhuman hopes into motion would require an inwardly directed transformation of the self. LaVey and his church appreciated this egoistic pursuit but disagreed with its implementation. Instead, he preached that change could be better elicited by obeying our carnal desires and directing our powerful emotional energies outward onto the world. Much of The Satanic Bible (with portions of it appropriated from Ragnar Redbeard’s hedonistic 1890 manifesto, Might Is Right, or The Survival of the Fittest) therefore focuses less on meditative introspection than on using ceremonial magic to manipulate people and things in order to sate the material desires of the satanist.20

LaVey in his San Francisco house, ca. 1960s.

It was within this realm of ritual magic where LaVey’s musical skills reemerged. The Church of Satan grew out of his black-painted San Francisco home in the late 1960s, where he hosted black masses on Friday nights for a wide-eyed public and press corp. These were, essentially, psychodramas that parodied the religious services of the Roman Catholic Church, mocking the Church with a dose of its own steroidal self-importance. Naked women as altars, chants invoking various demons, and snide, grandiloquent diatribes from The Book of Satan delivered over LaVey’s subtle pipe organ were all part of the elaborate mise en scène. Evidence of these proceedings can be heard on The Satanic Mass, recorded and released in 1968.21

It’s clear in the black masses and LaVey’s public, costumed persona that early satanism was no secretive mystery cult—it was a spectacle conjured primarily by artists, who successfully employed a sensational array of props, language, and artist-celebrity cameos (Mick Jagger, Jayne Mansfield, Sammy Davis Jr., et al) in order to quickly mesmerize a nationwide audience. It wasn’t until the early 1970s that the public events ceased and a more reclusive LaVey decided it was time to “stop performing satanism and start practicing it.”22He declared that the black mass was theater that could be performed by anyone, whether satanist or not; the real satanic ceremony, however, was a more serious, intimate affair.23This admission suggests that The Satanic Mass and its underlying soundtrack are not, in fact, satanic. In addition, we’d also be dead wrong if we were to try locating the satanic in the heavy metal of the 1970s and ’80s or the Norwegian black metal of the early 1990s. LaVey was extremely disdainful of these forms, whose content and sheer volume seemed to only deaden the senses and emotions—a major “sin” in the satanic lexicon—and which he believed was using satanic symbolism as little more than marketing artifice.24

This all then begs the question—did LaVey, or anyone, ever successfully produce any truly satanic music?

Fast-forwarding past the short-lived satanic panic of the early 1980s and landing in the early ’90s, when satanism was rapidly disappearing from the public eye, we find LaVey ready to set the record straight. He reemerged with a media blitzkrieg, including a biography, a documentary film, and two new albums of his own “no bullshit” satanic music, all shortly before his death in 1997.25

Strange Music (1994) and Satan Takes a Holiday (1995) reveal something quite the opposite of metal’s thundering drums and amplified guitars: covers of Tin Pan Alley songs, with all melody, harmony, and rhythm parts played by the Black Pope himself (and an occasional guest vocalist) on at least six stacked synthesizers, all in one take.26At first glance, this grating collection of songs realized with canned synthesizer seems sentimental at best and comedic at worst, but a brief review of the tenets of satanism reveals that this unlikely music actually fits well within the Luciferian canon as outlined by its progenitor.

The albums contain more than two dozen deviant songs mostly from the early part of the 20th century and are packed with innuendo: “Softy, As in a Morning Sunrise” (1928), which speaks of the passion of casual lovemaking that often expires in the early-morning light; “Gloomy Sunday (The Suicide Song)” (1933), which purportedly drove people to suicide when they first heard it and which has been covered by everyone from Billie Holiday to Björk; and “Dixie” (c. 1859), the Confederate-era anthem made famous by black-faced minstrel performers, just to name a few. 27For satanists looking to manipulate the world around them, “anything which serves to intensify the emotions during a ritual will contribute to its success.”28LaVey seems convinced that these risqué songs serve as a kind of satanic DNA, indexing humankind’s innate sensual memory, and that through such wordplay and melody we can easily stimulate or synthesize an ecstatic, magical existence. In addition, preservation of our immoral history is fundamental to satanism because it connects today’s sensual desires to a carnal continuum that began with the birth of man. In the words of noise artist and self-proclaimed satanic priest Boyd Rice, LaVey is an “ecologist,” preserving the obscenity and natural urges poetically embedded in the popular music of previous generations “for a world that is yet to come.”29

Still, in the presence of his music, we’re faced with a challenging listen. The excessively MIDI-sampled instrumentation flattens 1930s cabaret songs like the “The Mooche,” rendering them comedic and circuslike and seeming to lack any tangible sensuousness.30But here again we find satanism—a two-faced creed of semigenuine religious foray. Although his music isn’t necessarily experimental in form, LaVey is an antagonistic avant-gardist who’s extremely hostile to the complacency and blandness of contemporary popular culture. The sound of satanism is therefore the sound of difference, the sound of a music that you don’t want to listen to. Contrast these “aesthetic terrorists” with the masters of assimilation—the musicians of late-20th-century Christianity, who have been extremely successful in composing a gospel resembling Disney songs, rock and roll, and even rap and Christian “metal.” LaVey’s one-man band demonstrates satanism’s infatuated embrace of uncompromising, self-satisfied, alienated individuality, similar in some ways to ahbez’s lonely wanderer. These albums, then, are the egomaniacal satanic masterworks of one man in a recorded universe where he is finally the king of his own masturbatory, musical jungle.

Pauline Oliveros’s Environmental Dialogue

Animals are Deep Listeners. When you enter an environment where there are birds, insects or animals, they are listening to you completely. You are received. Your presence may be the difference between life and death for the creatures of the environment. Listening is survival!

—Pauline Oliveros, Deep Listening31

Pauline Oliveros’s (b. 1932) early career was decidedly more humble and less prone to proselytizing than that of eden ahbez and Anton LaVey. She was a pioneer of experimental and electronic music in 1950s and ’60s San Francisco, and her new perspectives were primarily confined to the abstract world of avant-garde art music. Although she’s known for a number of advancements in these fields, perhaps the most interesting is her radical re-conceptualization of the relationship between the composer, the performer, and the audience member.32Rather than furthering the modernist view of the composer and performer as virtuosic geniuses delivering work from on high, she reimagined them as humble acoustic observers—sharing more in common with their audience—whose mission was to facilitate a consciousness-expanding group-listening experience.

The ♀ Ensemble performing Teach Yourself to Fly from Sonic Meditations, 1970, Rancho Santa Fe, CA, (foreground to the left around: Lin Barron, cello, Lynn Lonidier, cello, Pauline Oliveros, accordion, Joan George, bass clarinet. Center seated foreground to the left around voices: Chris Voigt, Shirley Wong, Bonnie Barnett and Betty Wong). Pauline Oliveros Papers. MSS 102. Mandeville Special Collections Library, Univerisity of California, San Diego.

After 30 years of experimentation in sonic meditation, Oliveros developed Deep Listening, a program of contemplative listening and sounding exercises that coaches participants to become exceptionally receptive acoustic observers. For Oliveros, the sounds of the environment—what we might liken in some ways to Adolph Just’s voice of nature—“carry intelligence” and require our protection from the encroachment of industrial and technological noises, which threaten to mask or silence them altogether.33 By striving to listen inwardly and outwardly 24 hours a day, practitioners aim first to foster their own personal transformation through dialogue with their environment. After practice, however, Deep Listening becomes a tool for something more significant; Deep Listeners form a humble cadre of acoustic ecologists, whose listening practices help connect them “to the whole of the environment and beyond,” potentially enabling them to help preserve our natural soundscapes for future generations.

Oliveros’s own transformation began in the late 1950s, when she made environmental recordings from the window of her home. After rewinding and listening back, she found that the recording had captured sounds that she hadn’t heard at the time of recording. She henceforth devoted herself to being more acoustically receptive by “listening to everything all the time,” even while performing.34 Then, in tandem with the 1960s American counterculture’s embrace of Indian music, Oliveros and contemporaries like La Monte Young began implementing long tones and drones, slowing tempos down to a near-standstill, so that listeners could more easily focus on “the beauty of the subtle shifts in timbre and the ambiguity of an apparently static phenomenon.”35 Such experiments marked, perhaps, the beginning of her interest in considering active listening in music as a form of sitting meditation.36

After nearly a decade investigating this textural depth of sound, Oliveros had a breakthrough in 1969, when she began merging the physical gestures of her solo voice and accordion improvisations with the deep breathing and slow movement of her t’ai chi ch’uan practice. The connection immediately lessened her anxiety and left her feeling physically and mentally refreshed.37 During the winter of 1973, she explored this discovery at the University of California in San Diego with a group of musicians and nonmusicians who met for nine weeks of near-daily experimentation. What emerged was a series of sonic meditations—Fluxus-like text scores with instructions that are delivered like guided meditations and require no musical training to perform. They focus instead on various forms of listening and responding, incorporating sounds heard, remembered, imagined, and generated by the listener herself, while exercising participants’ telepathic capabilities as well.38

This ushered in a dramatic shift in Oliveros’s personal focus that, during the next decade, positioned sonic meditation as her primary endeavor and her music as simply “a welcome by-product of this activity.”39With this new perspective, she left Southern California in 1981 for upstate New York, where she spent another decade studying “Zen, Tibetan Buddhism, yoga, and Taoist forms” alongside her musical practice. This eventually culminated in her first week-long Deep Listening retreat in 1991, and after interest continued to grow, a subsequent Deep Listening three-year certification program soon emerged in 1995 that qualified others to teach the discipline. Her retreats typically took place in remote, “unspoiled location[s] with very little technological sound intrusion” so that participants could practice listening to the intelligent sounds of the natural environment without the masking effects of urban living.40

Deep Listening Retreat held at Dartington Hall, Devon, England, July 20-24, 2009. Photo: Richard Povall. © Aune Head Arts

As with many of the essence faiths of the 1960s and ’70s, Deep Listening promotes the belief that an introspective spiritual practice might yield peaceful effects out in the world. Oliveros points to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to outline her conviction in such human potential: “There is no such thing as mere observing…every observation we make is bound to act on the object we observe.”41 And so like many of these faiths, Deep Listening provides tools that are partly combative, partly palliative—in this case, taking aim at an increasingly technologized, industrialized, and populated world that threatens to erase our natural sonic resources, while attempting to alleviate the anxiety facing those waging the battle.42Having witnessed such deterioration firsthand over her lifetime, Oliveros warns us that preservation of the intelligence of nature is essential for ensuring the survival of the human race.43Within this worldview, performance and spectatorship no longer need to be understood solely within a musical framework: The recasting of scores as meditation scripts and of listening as a form of meditation and sonic vigilance suggests a repurposing of the performance space into a listening temple, where we might rehearse for the variety of spiritual and social challenges that lie ahead.

Here musical and spiritual practices become co-supportive of, if not indistinguishable from, one another. As art historian Donald Preziosi puts it, art and religion together present approaches “to the same question of the ethics of the practice of the self, of how self-Other relations are to be coordinated.”44The Deep Listener comes to us as a healer and facilitator, aiming to listen to and soothe the anxieties of the self, the Other, and the world. Oliveros’s listening ethic proposes to realign and reinvigorate these relationships by simply returning to and listening to “the sounds from the environment.” The voices of nature carry with them the sounds of survival and communion and call us to act, to “reinforce” them. Through this simple process “a kind of music occurs naturally. Its beauty is not through intention, but is intrinsically the effectiveness of its healing power…the music relates to the people who make it through participation and sharing, as a stream or river whose waters offer refreshment and cleansing to those who find it.”45