Second Life: Chrysalis Magazine

by Jenni Sorkin

For our Second Life series, we work with writers and publishers to present selected essays, magazines, ephemera, and other previously published material that is out of print or hard to find, giving it a second life online.

Jenni Sorkin reflects on the feminist publication Chrysalis.

To download a PDF excerpt of Chrysalis: A Magazine of Women’s Culture, Issue 1 (1977), click here.

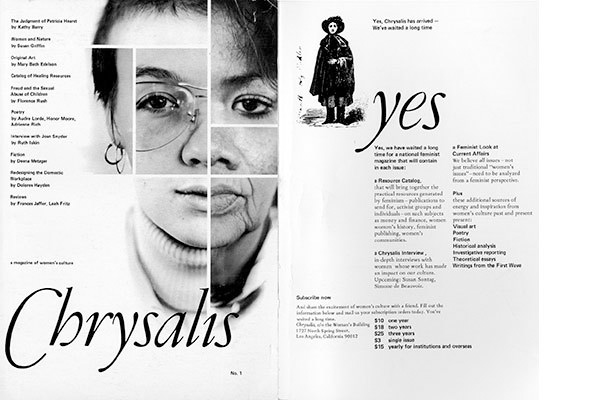

Chrysalis: A Magazine of Women’s Culture (1977-1980) was a short-lived, but influential feminist publication that was collectively produced by artists and writers active in the Los Angeles feminist movement. Chrysalis’ complete integration of art, literature, and cultural studies was distinct from other journals of the era, in particular, Heresies, which began the same year in New York. While Heresies remains the better-known publication, it is Chrysalis that engaged a broader public, covering progressive issues that affected the women’s community at large without taking an insular view of art world-only politics, or the thematic issues for which Heresies became widely known.

Through the efforts of editors Susan Rennie and Kirsten Grimstad, Chrysalis managed to cultivate a roster of high profile, nationally-known writers (Mary Daly, Robin Morgan, Adrienne Rich) and a modest circulation beyond greater Los Angeles, of roughly 13,000 subscribers. Housed at the Woman’s Building on Spring Street, in downtown Los Angeles, the journal collaged articles on women’s health, movement politics, as well as commissioning new fiction, poetry, and art portfolios. Throughout the 1970s, self-publication was critical to the success and maintenance of feminist communities. As a tenant at the Woman’s Building, this meant that Chrysalis had a built-in audience: the Feminist Studio Workshop, the separatist women’s art school that was the Building’s primary raison d’être.

Intended as a quarterly, the collective produced just ten issues over a span of three years, disbanding due to a chronic lack of funds. Yet Chrysalis was also mired in the bureaucracy of consensus, as editorial decisions were (for better or worse) the result of a collective process, in which everyone was compelled to agree to get to a decision. This leaderless approach was a syndrome of the feminist process itself, a by-product of the consciousness-raising structure. In making sure everyone had a voice, decision-making became woefully inefficient. Designed to foster the camaraderie and communalism, this philosophy had—and has—merit: in today’s era of extreme individualism, it feels like a breath of fresh air.