The Surrealist Bungalow: William N. Copley and the Copley Galleries (1948-49)

by Jonathan Griffin

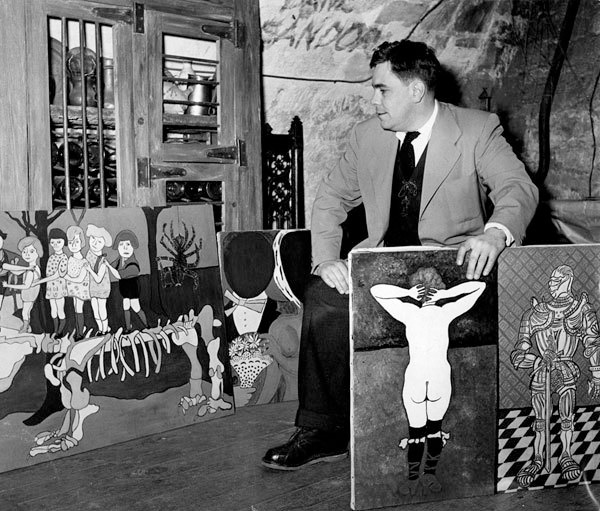

William N. Copley with his own paintings in Paris, 1951, two years after he closed the Copley Galleries and left Los Angeles. Photo: Mike De Dulmen. Courtesy the Estate of William N. Copley.

“No one in their right mind would have considered trying to open a Surrealist gallery in the California environment, which, of course, is what we decided to do late one whiskied evening,” wrote the artist and collector William N. Copley. “In the white haze of the morning after, we were both too proud to perish the thought.”1

It is fortunate for us that they didn’t. The Copley Galleries, founded by Copley and his brother-in-law, operated in Beverly Hills for just six months in 1948 and 1949. It may have been a spectacular failure, but it was also the inadvertent seed of one of the most important collections of Surrealist art in the United States. Years later, Copley would be the first owner of Marcel Duchamp’s masterwork Étant donnés (1946–66). He would also become recognized late in life as an accomplished and profoundly idiosyncratic painter.

In 1947, Copley, adopted son of newspaper tycoon Ira C. Copley, was 28 years old. As with many young men, his world was shattered by his wartime experiences of combat in Europe, and he returned to California divested of any convictions about the direction his future should take. It probably didn’t help that his family was fantastically wealthy, nor that he had been an aimless student while at school at Phillips Andover and Yale.

In a bid, perhaps, for domestic normalcy, Copley had found himself a wife, Marjorie Doris Wead, whom he married in 1945. Within three years they had a son, William, and a daughter, Claire.2 Within six, they were divorced. It was Marjorie’s sister’s eccentric husband, John Ployardt, who introduced Copley to a way of life that he had hitherto not even considered. Ployardt was an artist—he also had a day job drawing characters and doing voice-overs for Disney that he hated—and an acolyte of the Surrealist movement. “Surrealism,” wrote Copley, “made everything understandable: my genteel family, the war, and why I attended the Yale Prom without my shoes. It looked like something I might succeed at.”3

Max Ernst exhibition at the Copley Galleries, ca. 1949. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the William Nelson Copley papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

At this time in Los Angeles, there was scant interest in Surrealist art and little opportunity to exhibit or view it. Although local collectors such as Walter and Louise Arensberg were amassing important collections of advanced modern art, the few museums that existed in Los Angeles were reluctant to show it. The Los Angeles County Museum was, in Copley’s words, “a mausoleum of a structure […] which harbored some misacquisitions of William Randolph Hearst and a few stuffed animals.”4 Further east, the fledgling, privately run Pasadena Art Institute had yet to receive its bequest, in 1953, of Galka E. Scheyer’s spectacular collection or to change its name a year later to the Pasadena Art Museum.

Most commercial galleries either existed in the lobbies of big hotels—notably, Dalzell Hatfield in the Ambassador Hotel, Cowie Gallery in the Biltmore, and Francis Taylor Gallery in the Beverly Hills Hotel—or, as with Felix Landau’s Fraymart Gallery on Melrose, grew out of framing shops.5 They mainly showed the work of California artists, who, according to Copley, “had just discovered abstract art.”6

It just so happened, however, that at around the time that the “whiskied” Copley and Ployardt were planning their Surrealist gallery, an association of assorted philanthropists that included the Arensbergs and the actor Vincent Price was inaugurating a nonprofit gallery on Rodeo Drive. The Modern Institute of Art opened in February 1948 “with the goal of becoming the West Coast equivalent of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.”7 Its first exhibition included works by Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Henri Matisse, and Marcel Duchamp—avant-garde artists of a stature rarely seen in Southern California but who, in the late 1940s, no longer seemed contemporary to Copley and Ployardt.

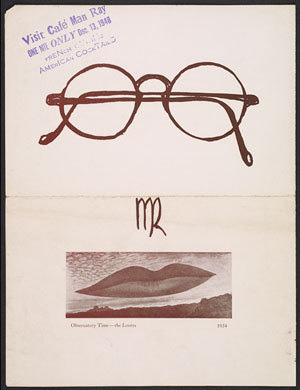

Man Ray exhibition catalogue announcing “Café Man Ray” at the Copley Galleries, December 1948. Courtesy of the William Nelson Copley papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

The duo’s first stop in recruiting artists was the studio of the Surrealist closest to home. Man Ray, who had lived in Los Angeles since 1940, was disappointed that he had failed to carry his elevated status with him from Europe to California. He was recognized, if at all, as a photographer and had failed to make the inroads he had hoped to in the film industry. When Copley and Ployardt knocked on his studio door the second time, he let them in. The first time, one day around 11 a.m., he sent them away and told them to return at a more civilized hour.

Man Ray’s recollection of Copley was of a typical college graduate: “inarticulate in certain respects but without the usual expression of one determined to make a respected position for himself in the world.”8 For his part, Copley thought that “he seemed grudgingly glad to see us. I think he was touched by our youth and lunacy and our homage.”9

Man Ray agreed to an exhibition on the following terms: that Copley and Ployardt could guarantee the sale of at least 15 percent of the work and that he would have complete autonomy over its selection and hanging. A deal was struck, and the three became close friends.10 Perhaps even more valuable to the fledgling gallerists, however, was Man Ray’s introduction of the pair to Marcel Duchamp. In the spring of 1948, they flew to New York to meet him.

Meeting Duchamp was much less straightforward than meeting Man Ray. A letter was sent, and the artist replied by postcard, with instructions to come to the lobby of the Biltmore Hotel at noon the next day. Wrote Copley: “We found what had to be Marcel smoking a pipe in the recesses of a couch built for a lot of people. Only he could be Duchamp, a little shabby but dignified, like maybe he was waiting for a bus. He appeared amused by our groveling apologies. ‘But not at all. I like it here. I often come just to ride the elevators.’ Somehow we could imagine him doing just that.”11

In 1948, Duchamp was, of course, in self-proclaimed retirement from his career as an artist. There was no point in asking him to exhibit. Instead, Duchamp put them in touch with dealers of Surrealist art across the city, notably Alexander Iolas, in whose gallery Copley and Ployardt inadvertently encountered “a gaunt, cadaverous” man who proceeded to pull a series of boxes from a paper shopping bag. His name was Joseph Cornell. According to Copley, “We bought all his boxes and took him to lunch. He looked hungry. Afterward, he asked if he could have an ice cream soda. He seemed afraid we would say no.”12 Duchamp also sent the pair to meet the artists Roberto Matta, who agreed to show, and Isamu Noguchi, who did not. “He was unpleasant,” recalled Copley, “and wanted to know, since we made a point of labeling ourselves a Surrealist gallery, what guarantee would he have that we wouldn’t show a sculpture of his next to an old shoe. Since we didn’t like his question, we didn’t offer the guarantee. That one ended badly.”13

Exterior of the Copley Galleries at 257 North Canon Drive in Beverly Hills. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the William Nelson Copley papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Back in Los Angeles, Copley and Ployardt were flush with the success of their trip. Ployardt quit his job at Disney, and Copley sold his house in order to afford the rent on a bungalow at 257 North Canon Drive in Beverly Hills. They paid $250 for a brass plaque with “Copley Galleries” inscribed on it. (Since the capital came from Copley—or rather Copley Sr., who died in 1947—it was his name on the door.) Then they bought a pet capuchin monkey, principally, it seems, because they would be probably the only gallery in the world with a monkey.

Their final pilgrimage was to Sedona, Arizona, where another European exile, Max Ernst, was living with his American wife, Dorothea Tanning, in “a landscape that Max had painted before he ever saw it.”14 Despite Duchamp’s introductory telegram getting badly garbled and Tanning returning home from a spell in the hospital only that morning, the artist couple were eminently hospitable to their young visitors, and Ernst readily agreed to exhibit his work with them. (Tanning also agreed, although for reasons they did not anticipate, time ran out before her show could take place.)

The Copley Galleries opened its doors in September 1948 with an exhibition of more than 30 paintings by Magritte, all consigned from Iolas. The gallery retained its domestic features—fireplaces, polished wood floors, pillars, alcoves, and latticed wooden room dividers—but was elegant and well lit. In a letter to Walter Arensberg, the pair declared, “We intend to present art as a dynamic way of living rather than interior decoration.”15 They published catalogs for every show and had ambitiously produced invitation cards. They engaged Francoise Stravinsky, daughter-in-law of the composer, as their secretary. “She didn’t type too well, but we kept this from her,” said Copley. “We’d send her on errands, and I’d type the letters over. I didn’t type too well either. But we adored her and it was a great name to bandy about.”16

At the opening for the show, the monkey leapt on shoulders and guests worked their way through the free drinks with gusto. The next day, with no sales, the hungover Copley and Ployardt were getting nervous until a collector called Stanley Barbie lurched drunkenly through their door. After many more drinks, they sold him two Magritte paintings. It was to be the only successful sale that they would make.

Rene Magritte exhibition at the Copley Galleries, ca. 1949. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the William Nelson Copley papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Copley had decided to apply Man Ray’s condition of 15 percent guaranteed sales to every show at the Copley Galleries. In order to fulfill this promise to Iolas, he was forced to buy a number of Magritte paintings himself. Magritte’s painting The Liberator (1947) currently hangs in LACMA’s Ahmanson building, acquired by Copley from his first exhibition in Beverly Hills.

Next came the show of boxes by Cornell. Copley and Ployardt were so pleased with the announcement flyers they had designed that they “all but papered the walls and ceiling” with them.17 Originally purchased from Cornell for $50 each, the boxes were priced between $100 and $200. None sold, and many were subsequently given away as gifts. Irving Blum did not see the original show but later recalled, “While walking down Santa Monica Boulevard, years later, I passed a thrift store and noticed on a high shelf a Renaissance Princess made, I believed, by Joseph Cornell. I bought it for $50. I called Bill [Copley], and he indeed remembered the work. He was amused that twenty years past his time the price remained the same.”18

Copley and Ployardt were disconcerted when they uncrated the paintings for their next show, by Matta. “They seemed too much like abstractions for our catholic taste,” wrote Copley.19 But as with much of the work they showed, their understanding of it was deepened gradually by the month or so they spent with it in their regrettably quiet gallery. The same went for Yves Tanguy’s “vast nightlike landscapes, peopled with boneyard presences casting mile-long shadows,” which invaded the pair’s dreams.20

“It was at the end of the Matta show that the monkey decided he’d had it with us. All I saw was his streak as he headed down Cannon [sic] Drive and across Wilshire Boulevard against a red light, causing [a] near accident and people to swear off drinking. There was a movie house right there, and he disappeared from view underneath the turnstile,” wrote Copley. Fortunately, the animal took up with the proprietor of the gas station down the road. They replaced him with a cockatiel. “The bird was sweet and tame, and bird shit was easier to deal with than monkey shit.”21

A pattern was emerging: The Copley Galleries, with or without its capuchin monkey, enjoyed fantastically raucous openings attended by glamorous guests and the occasional Hollywood celebrity, then failed to clinch any sales. The city’s serious collectors of modern art, of which there were few, simply weren’t yet confident enough to invest in art this unnerving and confrontational, despite the fact that its practitioners were all famous in Europe and some even in New York. Either that, or they lacked confidence in this brand-new gallery run by two irreverent young men with only a pet monkey for credentials.

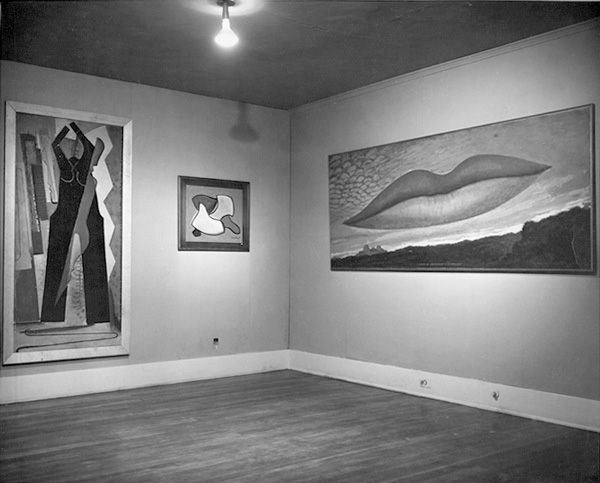

Man Ray exhibition at the Copley Galleries, ca. 1949. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the William Nelson Copley papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Finally, it was Man Ray’s turn. In the intervening months, Copley and Ployardt had seen a lot of the artist, which, Copley confessed, had its advantages and disadvantages from a professional standpoint. “Artists, like mothers-in-law, are often better appreciated when a certain geographical distance is maintained.”22Holding tight to his contractually agreed autonomy, Man Ray did not reveal until the last minute whether he would exhibit any photographs at all, so resistant was he to his prevailing reputation as a photographer. In the end, he did for the sake of commercialism, but he simultaneously published a text in the show’s catalog titled “Photography Is Not Art.” He called his exhibition, sardonically, “To Be Continued Unnoticed.” It included paintings from 1914 onward, photographs, Rayograms, posters done in airbrush on cardboard, and his iconic sculpture Cadeau (Gift) (1921), which consisted of an iron studded with a line of nails. The show was dominated by his large painting Observatory Time, the Lovers (1936), showing his former lover Lee Miller’s lips floating over the Paris Observatory.23At the opening, they transformed the bungalow’s front patio into a French café. Francoise Stravinsky served French onion soup and red wine, and the artist made a sign that read “Café Man Ray.” Again, nothing sold except for the 15 percent of works bought by Copley for his rapidly growing collection.

In an instance of life imitating (Surrealist) art, Beverly Hills was blanketed in snow for the opening of Max Ernst’s exhibition.24 The show, Copley claimed, was the first full retrospective of Ernst’s art ever held. It is hard to imagine how the one-story bungalow could accommodate the 300-odd pieces that were lent by collectors and dealers, including Julien Levy, Alexander Iolas, Pierre Matisse, Walter Arensberg, and Roland Penrose. Even New York’s Museum of Modern Art improbably sent their Ernsts to Beverly Hills.

Though all their exhibitions had been received with more or less total indifference by the local public, the lack of appreciation for the great Ernst exhibition was all the harder for Ployardt and Copley to take because of the tremendous amount of effort they had invested. The only people who seemed remotely interested were a gang of ten-year-olds who regularly came to study the paintings and were “quietly, seriously, profoundly mesmerized by the fantasy of Max Ernst. It was a mini version of the success we’d dreamed of.”25

The Copley Galleries’ accountant was reportedly “the unhappiest bookkeeper on the West Coast”; by spring of 1949, the evidence of the business’s unviability was indisputable, and the gallery closed.26 The Modern Institute of Art, similarly plagued by financial troubles, also closed its doors that spring.

Max Ernst exhibition at the Copley Galleries, ca. 1949. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the William Nelson Copley papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

To Copley, Ployardt and Man Ray, a brief moment of heady excitement and possibility had come and gone. Ployardt reluctantly returned to work at Disney. Copley’s return to domestic life was unhappy, too; by 1950, he was living in a converted firehouse with his girlfriend, artist Gloria de Herrera. He was devoting more of his time to painting and, inspired perhaps by Duchamp, was also presiding over chess tournaments. In 1951, Copley, Herrera, and Man and Juliet Ray set sail from New York to Paris. Duchamp waved them off.

Although as time went by he preferred to be known in his own right as a painter, Copley continued to collect Surrealist art. His collection grew and grew; it came to include Magritte’s famous The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe) (1929) and Richard Hamilton’s $he (1958–61), as well as works purchased from his own gallery: Ernst’s Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (1944) and Surrealisme et le peinture (1942), Cornell’s large Soap Bubble Set (1948) and Man Ray’s Observatory Time, the Lovers. When, in 1966, Duchamp revealed that he had been working for the last 20 years on the installation he called Étant donnés, it was to Copley that he turned in search of a buyer. It was sold on the condition that Copley donate the work to the Philadelphia Museum of Art upon Duchamp’s death, and it was in his possession for only two years, whereupon Copley kept his side of the agreement. In 1979, when he began to feel burdened by ownership and realized he had burned through most of his inheritance, he sold the rest of his collection at Sotheby’s.

Despite Copley’s commitment to Surrealism and his friendship with its artists, his own work did not fit neatly within the category. His paintings of smartly dressed men and the curvaceous femmes fatales whom they lust after may have drawn in part from Magritte’s absurdist tableaux, but his cartoonish, decorative style anticipated the work of artists like John Wesley and Tom Wesselmann, commonly associated with Pop art. Copley painted until the end of his life, when he died in 1996 at the age of 77 at his home in the Florida Keys. He signed his paintings CPLY—perhaps in an effort to distance his persona as an artist from his other life as an important collector.27 Of his work, Man Ray said, “It conformed to my repeated declaration that art was the pursuit of liberty and of pleasure.”28

Left to right: Man Ray, Juliet Ray, William Copley, and Marcel Duchamp aboard the S.S. De Grasse, before their departure for Paris on March 12, 1951. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Estate of William N. Copley.

The Copley Galleries may now be little remembered, but this reckless experiment by two wealthy young men who had little idea what they were doing except pursuing liberty and pleasure continues to resonate down the decades. Surrealism arguably came to have a greater influence on the art made in Los Angeles in the latter half of the 20th century than any other historical movement. It is hard to claim, of course, that the influence originated in Beverly Hills in 1948. Today, 257 North Canon Drive is a parking lot. Aside from two works by Magritte—The Liberator and The Treachery of Images (This Is Not a Pipe) —which came to LACMA via a more circuitous route, little of Copley’s collection ended up back in Los Angeles. As Copley recalled Man Ray once saying, “There was more Surrealism rampant in Hollywood than all the Surrealists could invent in a lifetime.”29 The city, perhaps, had no need for an establishment like the Copley Galleries.