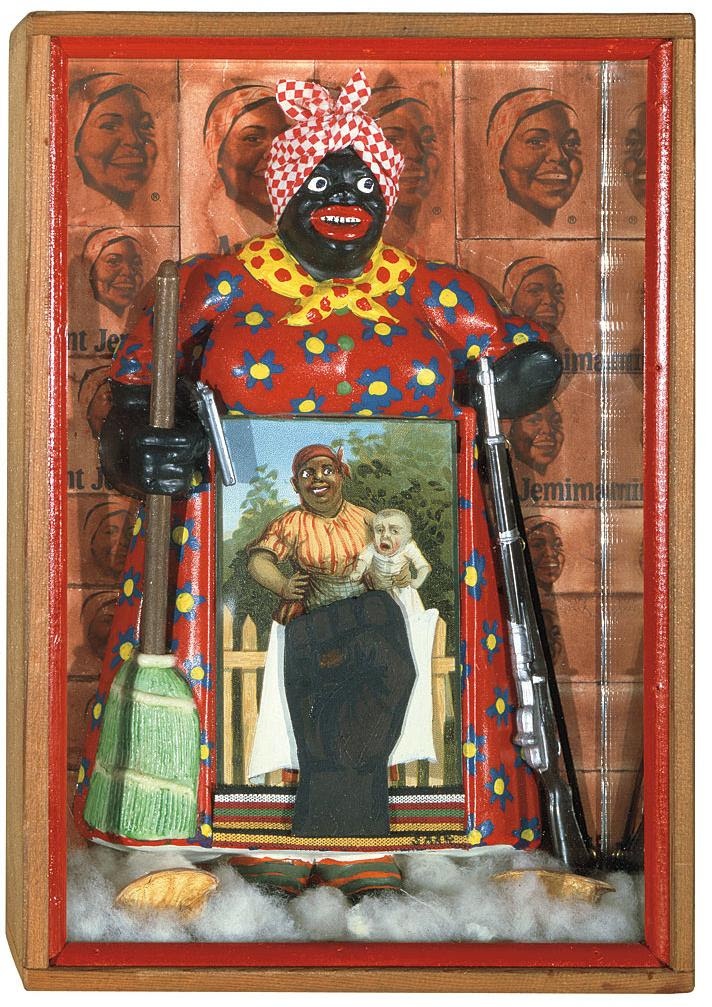

Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, 1972

The headline in the New York Times Business section read, “Aunt Jemima to be Renamed, After 131 Years.” One might reasonably ask, what took so long? The Quaker Oats company, which owns the brand, has understood it was built upon racist imagery for decades, making incremental changes, like switching a kerchief for a headband in 1968, adding pearl earrings and a lace collar in 1989. PepsiCo bought Quaker Oats in 2001, and in 2016 convened a task force to discuss repackaging the product, but nothing came of it, in part because PepsiCo found itself caught in another racially fraught controversy over a commercial that featured Kendall Jenner offering a can of their soda to a white police officer during a Black Lives Matter protest.

The original pancake mix and syrup company was founded in 1889, and four years later hired a former slave to portray Aunt Jemima at the World’s Fair in Chicago, playing the part of the happy, nurturing house slave, cooking hundreds of thousands of pancakes for the Fair’s visitors. This enactment of contented servitude would become the consistent sales pitch. In the 1930s a white actress played the part, deploying minstrel-speak, in a radio series that doubled as advertising. In print ads throughout much of the 20th Century, the character is shown serving white families, or juxtaposed with romanticized imagery of the antebellum South – plantation houses and river boats, old cottonwood trees. From its opening in 1955 until 1970, Disneyland featured an Aunt Jemima restaurant, providing photo ops with a costumed actress, along with a plate of pancakes.

In 1964 the painter Joe Overstreet, who had worked at Walt Disney Studios as an animator in the late 50s, was in New York and experimenting with a dynamic kind of abstraction that often moved into a three-dimensional relief. That year he made a large, atypically figurative painting, “The New Jemima,” giving the Jemima figure a new act, blasting flying pancakes with a blazing machine-gun. Some six years later Larry Rivers asked him to re-stretch it for a show at the Menil Collection in Houston, and Overstreet made it into a free-standing object, like a giant cereal box, a subversive monument for the South.

Around this time, in Los Angeles, Betye Saar began her collage interventions exploring the broad range of racist and sexist imagery deployed to sell household products to white Americans. An early example is “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima,” which shows a figurine of the older style Jemima, in checkered kerchief, against a backdrop of the recently updated version, holding a handgun, a long gun and a broom, with an off-kilter image of a black woman standing in front of a picket fence, a maternal archetype cradling somebody else’s crying baby. The forced smiles speak directly to the violence of oppression.

Following the recent news about the end of the Aunt Jemima brand, Saar issued a statement through her Los Angeles gallery, Roberts Projects:

“My artistic practice has always been the lens through which I have seen and moved through the world around me. It continues to be an arena and medium for political protest and social activism. I created “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” in 1972 for the exhibition Black Heroes at the Rainbow Sign Cultural Center, Berkeley, CA (1972). The show was organized around community responses to the 1968 Martin Luther King Jr. assassination. This work allowed me to channel my righteous anger at not only the great loss of MLK Jr., but at the lack of representation of black artists, especially black women artists. I transformed the derogatory image of Aunt Jemima into a female warrior figure, fighting for Black liberation and women’s rights. Fifty years later she has finally been liberated herself. And yet, more work still needs to be done.” — Betye Saar, June 17, 2020.

For an interview with Joe Overstreet in which he discusses “The New Jemima,” see:

https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/ey-exhibition-world-goes-pop/artist-interview/joe-overstreet