A CalArts Story

by Thomas Lawson

Screenshot of TV footage of the premiere of Mary Poppins at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Los Angeles, 1964. The premiere was framed as a founding fundraiser for California Institute of the Arts.

“It’s a wonderful night tonight, particularly for CalArts, because CalArts is a wonderfully inspirational idea and I wish there had been a university of the arts like this when I was a young man. And we are all delighted that Mary Poppins is dedicated to CalArts.”

—Director Robert Stevenson speaking on the red carpet at the World Premiere of Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins, the Chinese Theatre, Hollywood, August 27, 19641

In 1961 Walt Disney brokered a deal to save two beloved art institutions in Los Angeles, an art school and a music conservatory. He had been thinking of the commercial benefits of such a merger for some time, and had commissioned a report from the entertainment real estate consultants, Economics Research Associates (E.R.A.), on the feasibility of launching an arts complex anchored by a school of the arts, that would combine “a wonderland of exhibits and entertainments, theatres and shops and restaurants, studios and galleries.” Seven Arts City would be a place that would attract students from all over the world, provide entertainment and enlightenment, along with fine dining, to regular people, and allow the fine arts to touch everyday life.2The merger of the Chouinard Art Institute and Los Angeles Conservatory of Music was the first step in the planned creation of a “mecca for the art-minded or recreation-bound visitor, a major creative center designed around the nucleus of fine schools, each on its own landscaped campus.”3

Director Robert Stevenson speaking on CalArts at the premiere of Mary Poppins at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood, Los Angeles, 1964.

Over the next few years Disney brainstormed with a small group of associates—executives at his company, socialite friends—to draw up a plan for the centerpiece of this new concept in destination entertainment, the California Institute of the Arts. A first draft of sorts was unveiled at the Hollywood premiere of Mary Poppins, in the summer of 1964, an event that was framed as a fundraiser for CalArts. A short film envisages the new school as “an acropolis crowning the hills above Hollywood,” a partner to the Music Center and the County Museum of Art, both then under construction, in bringing cultural glory to Los Angeles.4What was shown was still fairly conventional—a string quartet, a painting class, students working a potter’s wheel—but the voice-over hinted at something more interesting. In this account CalArts would be an inclusive community of the arts, presided over by working professionals imparting theories and knowledge to young talent.

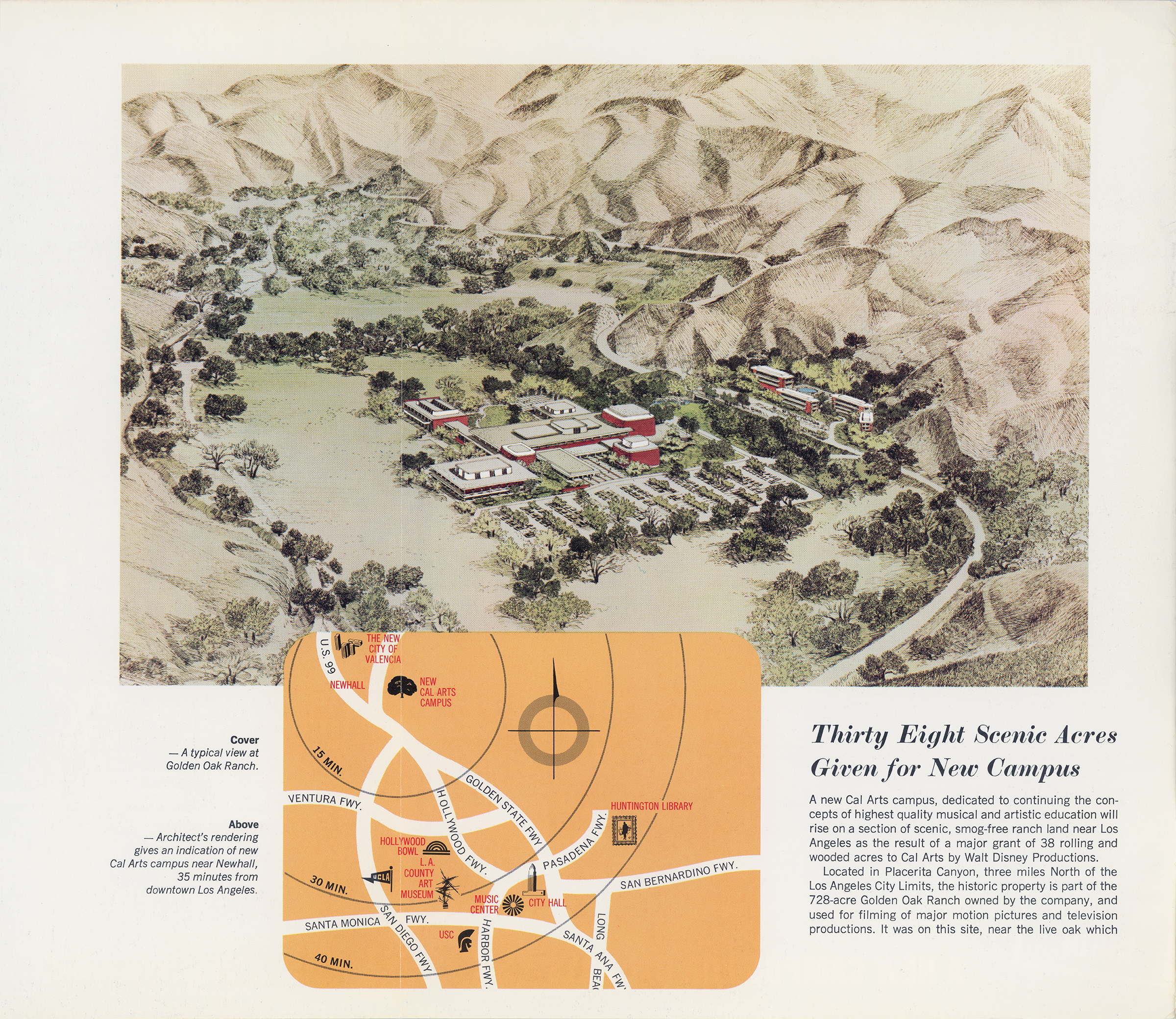

Disney envisaged an enchanted place where creativity would flourish, removed from the grit of city streets, a kind of gated community of the arts, not unlike his theme parks. But he soon soured on the idea of building in the Hollywood Hills; as a dyed-in-the-wool right-winger, he couldn’t abide the idea of paying taxes to the city he was intent on glorifying. As a better alternative he decided to place the campus on a section of the Golden Oak Ranch in Placerita Canyon, 30 miles north of Hollywood, near Newhall, a then sparsely developed section of live oak woodlands and chaparral in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains. The Ranch was a sprawling Walt Disney Productions (WDP) property used for location filming, and so offering up a small parcel was a good deal, financially speaking. A socially connected architecture firm from Pasadena, Ladd and Kelsey, was hired to design and build the new campus, with a view to having classes start in 1967. The architectural idea was to create a single large building that would support all the arts under one roof, with “large, light classrooms and studios, soundproofed practice rooms, acoustically sound areas for opera workshops, functional theatre and concert hall, and rooms designed for the work of such specialized studies as film arts and fashion design.” A promotional flyer for the project shows the large building and attendant parking lot set on a large meadow surrounded by trees, with the mountains rising behind. In discussing his design for a promotional flyer, Thornton Ladd said, “In general terms we hope to provide a thoroughly functional plant designed from modern materials to harmonize with the terrain, and its general atmosphere to be reminiscent of the classic, open beauty of the academies of ancient Greece.5

During the previous century the area had been famous for both gold and oil exploration, so it was perhaps no surprise that preliminary engineering studies discovered that geological problems made the land unsuitable for large buildings. In response Disney entrusted his long-time associate, Harrison ‘Buzz’ Price, to seek out an alternative. Price was perfect for the job; he was a specialist in leisure-time economic analysis, who, as the principal actor in E.R.A. had found the ideal spot for Disneyland, and was then working to site Walt Disney World in Florida. Price found a larger property about seven miles north, next to where the Newhall Land and Farming Company was beginning to develop part of their property into an ex-urban housing development to be named Valencia, a planned community that would be marketed as a refuge from inner city trouble. A deal was struck to place the CalArts campus adjacent to this enclave, just off the 5 Freeway as it headed north from the city, a perfect location to develop the larger arts attraction and shopping center that still had a claim on the WDP imagination. Ladd and Kelsey were tasked with adjusting their design for the new terrain, and a new opening date was set for 1970.

“A New Campus for CalArts” at The Walt Disney Co.’s Golden Oak Ranch in Placerita Canyon, pictured in a promotional brochure for CalArts from 1965. Walt Disney Productions deeded 38 acres to the CalArts Board of Trustees. Image courtesy of SCVTV.

Despite the promotional talk of a bucolic campus where artists would pursue their work in a protective isolation, Disney himself was beginning to articulate a more far-reaching vision of possibilities in line with his own ambitions. During the early development of Walt Disney World he was drawing up a concept to explore an experimental planned community to serve as a kind of think tank for American innovations in urban living, and he clearly saw the CalArts/Seven Arts City idea as a high culture version of the same thing. Although unashamedly working within the realm of popular entertainment, Disney considered his mix of film (both animation and live action), music, dance, and architecture to be in line with what Richard Wagner had prophesied as the future of the arts. In a two-page statement of intent, he wrote, “A hundred years ago Wagner conceived of a perfect and all-embracing art, combining music, drama, painting and dance, but in his wildest imaginings he had no hint what infinite possibilities were to become commonplace through the invention of recordings, radio, cinema and television.”6Disney began talking about the in-between areas of art, the areas where ideas overlap. He talked about wanting to create a center where artists could devote themselves to unique and experimental projects, aided by student apprentices. It seems that he stopped thinking about the new school as a centerpiece for an entertainment complex. He began to see his school as “a community of all the arts,” an incubator for a new kind of gesamkunstwerk.

In pursuit of this more purely educational idea, a longer document was developed, also by E.R.A. with Price as the likely author. This was a kind of prospectus for investors, spelling out both the need for this new kind of arts school, and the broader concept driving it. The argument for need was rooted in a Rockefeller Foundation study of American leisure time and a perceived deficit in the ranks of professional artists of all types. The problem to be solved was a supposed over-specialization in the arts, leading to static art forms bereft of originality; the solution was to develop an institution open to multi-disciplinary approaches, a place that would “draw artists and professionals interested in experimentation and research in new, collaborative art forms and innovative communications techniques.”7There was quite a bit of space given to warning about the stultifying effects of bureaucracy and academic requirements on the development of young artists, and it was recommended that no degrees be given. Instead, student artists would work with a range of professionals in a kind of laboratory situation, discovering and improving skills while considering how their work might demonstrate a responsibility to the wider community.8An example of what could be accomplished was to be found at the new Tisch School of the Performing Arts at New York University.

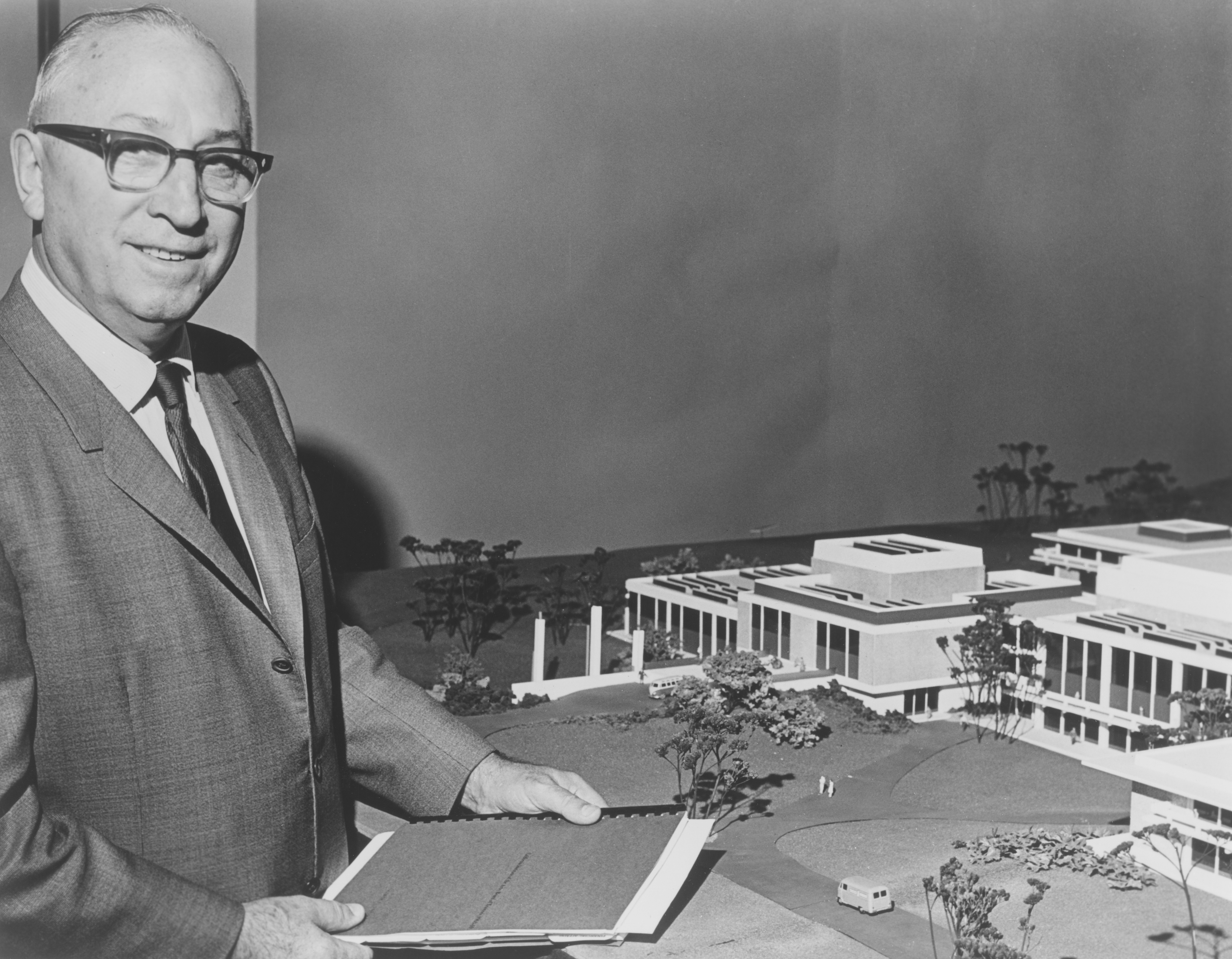

Roy O. Disney, Trustee of California Institute of the Arts, views a model of the new 60-acre campus, scheduled to open in Valencia in the autumn of 1970. The Institute, designed by the firm of Ladd and Kelsey, promised to provide over 718,600 sq. ft. in its 3-level building, to accommodate classrooms, workshops, studios, galleries, offices, and theaters. Image courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Walt Disney died suddenly at the end of 1966, a week after this Need and Concept document was completed, leaving the future of CalArts in doubt. The Board, now chaired by H.R. Haldeman, who would later serve as Richard Nixon’s Chief of Staff, began discussing a name change to the Walt Disney Institute, along with how best to proceed with developing the shopping center on the larger portion of the Valencia property. At the same time additional Board members were sought, including art patrons like Vincent Price, Simon Norton, and Robert Rowan, as well as political figures like Ronald Reagan. It appears that further discussion convinced the Board that changing the name would likely mean that WDP, the parent Disney company, would be forever held responsible for financing the school. The idea of developing Seven Arts City was shelved, and Walt’s brother, Roy, along with Price and the other senior company executives decided it was their duty to carry on with the plan outlined by E.R.A. A search was initiated to find the best minds in the country to bring Walt’s vision to reality, and as a result Haldeman hired Robert Corrigan away from Tisch to be the first President, and Herbert Blau, co-director of the Lincoln Center’s Repertory Company, to be Provost. Thus two of the most prominent institutional avant-gardists in the country came to guide CalArts into actuality.

Corrigan was an innovative arts educator who had been instrumental in the creation of Tisch, which had opened in 1965 as a place where professional artists and filmmakers would train in proximity to the broader academic resources of a research university. Before that he had edited The Drama Review for five years before handing it on to Richard Schechner, the influential performance theorist and director who later founded The Performance Group in New York. Blau was also a significant figure in experimental theatre, an iconoclastic director and theorist who had staged some of the earliest productions of Beckett and Genet in the United States, including a version of Waiting for Godot at California’s San Quentin State Prison, with Estragon, Vladimir, Pozzo, and Lucky played by inmates. An enthusiastic intellectual, Blau “was always ready to sit on any curb or any rehearsal floor to explore the practice of the experimental. On the stage and on the page, he never bought into the traditional split between practice and intellectual pursuits.”9Becket is said to have described him, with typical brevity, as “overpoweringly intellectual.”10

Within months of their hiring, Corrigan and Blau began assembling a roster of avant-garde and experimental figures to discuss and design a new kind of college where the corporate idea of a profitable interdisciplinarity would morph into an open learning space unfettered by rigid curricula or unproductive hierarchies between teacher and student. This was to be a place where ideas mattered, and where commerce would be sidelined:

“For the experimenter, being at the outer limits is an important condition for jarring into focus attention upon urgent issues, but the experimenter’s issues are philosophical rather than esthetic. They speak to questions of Being rather than to matters of Art… The temporary ambiguity of experimental action is quite appropriate, for in leaving art, nothing is really escaped from; as it is suppressed, it emerges in disguise… Experimental art is never tragic. It is a prelude.”

—Allan Kaprow in “California Institute of the Arts: Prologue to a Community”11

The Great Ground Breaking for CalArts in Valencia, California shows Mrs. Walter E. Disney (left), Mrs. Richard R. Von Hagen, Trustee and President of Walt Disney Associates, and Roy E. Disney (Walt’s nephew) about to unearth the plaque with the inscription, “I dig California Institute of the Arts.” Participating in the Great Ground Breaking were Secretary Robert H. Finch, Department of Health, Education and Welfare (center rear), who was principal speaker, Robert W. Corrigan (right), President, California Institute of the Arts, who presented him, and Donald Miller (left rear), Executive Producer and Vice President, Walt Disney Productions (and Walt’s son-in-law). Image courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Establishing an idea that the new college would enshrine a progressive vision of the arts, Corrigan and Blau brought in the atonal composer Mel Powell to lead the new Music School, and he in turn recruited the electronic pioneer Mort Subotnick. In parallel to this emphasis on new music, the great sitar innovator Ravi Sankar and the ethnomusicologist Nicholas England were brought on to create an entire department of non-Western music, with an emphasis on various kinds of percussion music from Africa, India, and Indonesia. Clearly there was to be no opera, nor even traditional orchestral music. Paul Brach, who had been a second generation Abstract Expressionist in New York before moving to San Diego to establish the art department at the State University there, was hired as the dean of the Art School, and he persuaded the theorist of “Happenings,” Allan Kaprow, to help him devise a school that would look beyond traditional genres. The nascent Film School was to be led by the narrative filmmaker Alexander MacKendrick, but would also include the experimentalist Pat O’Neill and the veteran animator Jules Engel. These people represented various generations of avant-garde thought and practice, and all at some level came to design schools and programs intended to train young professionals. But Corrigan, and especially Blau, were interested in thinking beyond this, in seeking ways to move past the limits of the traditional disciplines. Kaprow was seen as an important ally in this, and through him they began talking with a number of figures in the Fluxus orbit in New York: James Tenney, Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles, Nam June Paik, Peter van Riper, Simone Forti. Blau was also interested in social protest, and in 1968 joined about 500 writers and editors in pledging a war tax protest. Accordingly, he invited the design maverick Victor Papanek, who was an advocate of socially responsible product design, to be dean of the Design School, and asked the radical educator Maurice Stein to configure the general education component of the undergraduate curriculum.

Between 1968 and 1970, while the physical campus was being built, an ideal version of what it might contain was being discussed and imagined by a number of these participants. In his professional life Kaprow was already beginning to move past a critique of the art object to a much broader critique of modern society, and how methods of communication shape experience and politics. During these years he was thinking through the ideas that would see published form in three essays on “The Education of the Un-Artist,”12which argue for the superior value of playful discovery over both skill-based and de-skilled art making. As he would write, “the task for the experimental artist is to avoid making art—it is too easy in this time of non-art, anti-art, and art/art—everything has the potential to be art, anything that has caught the attention of an artist has that potential, so quit it.”13Kaprow’s goal was to encourage a new generation of “un-artists” who would discover an experimental ground where art might get lost in the paradox of being something else, and they would feel free to lose their professional identity. To reach this place of liberation, Kaprow proposed a curriculum that would focus on understanding the everyday environment as the crucible for thinking in the realm of art and beyond, working across all established professional boundaries. To do this there would be a seminar on Happenings, digging into his own disillusion, a series of symposia in which philosophers, physicists, anthropologists, social revolutionaries, and other multi-disciplinary thinkers would consider the relevance of the arts in relation to everyday life, and finally a variety of projects in public schools and local communities to test that relevance in a real way.

There is a deep humanism in Kaprow’s thinking here, one shared by Victor Papanek, who saw design as a tool for remaking society, and design education as much more challenging than the mere acquisition of skills. To Papanek, design that was solely focused on style had lost touch with what people need, and to counteract that he too was interested in considering the work through the various lenses of ecology and anthropology. In the first year at CalArts he had his students design ultra-cheap radios to be exported to Third World countries. But perhaps the most radical educationalist of the group was the sociologist, Maurice Stein, who used graphic design to upend the traditional hierarchies of the classroom, in an attempt to upend hierarchies everywhere.

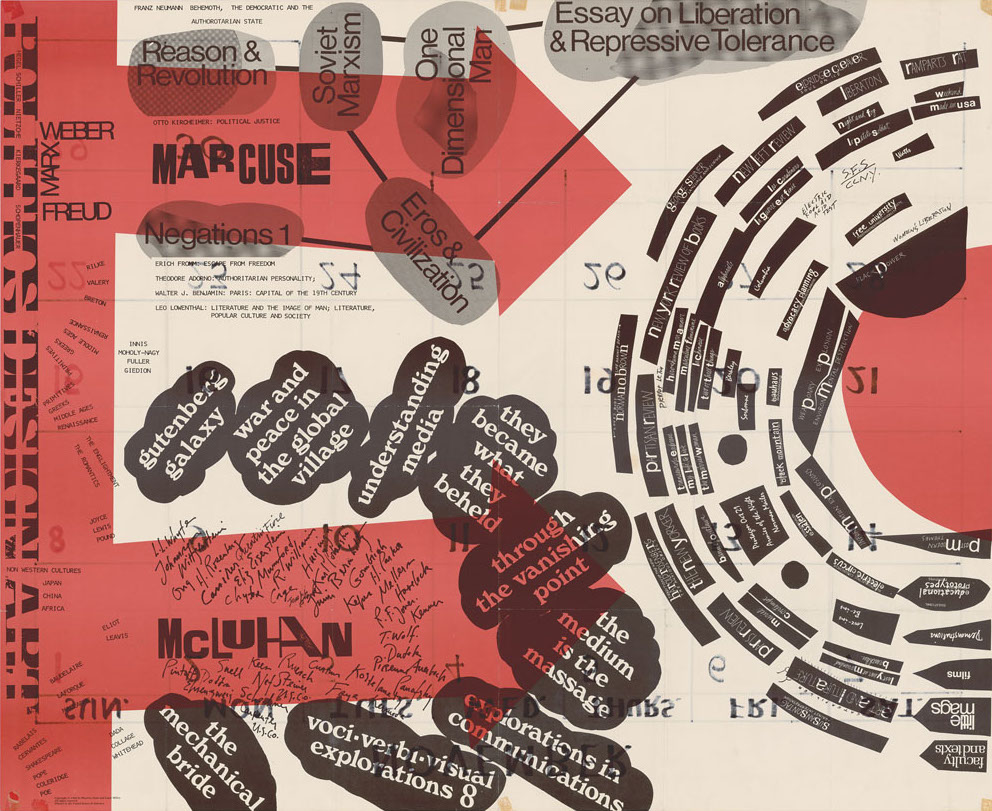

Poster from Stein and Miller’s Blueprint for Counter-Education, originally published in 1970 and reprinted by Inventory Press in 2016. Image courtesy of Library and Archives Canada (LAC).

Before coming to CalArts, Stein had been experimenting with open-ended, discursive teaching methods at Brandeis University. But in this new arts environment he was able to take his ideas further, developing, with co-author Larry Miller, the Blueprint for Counter-Education as a roadmap for the new department of Critical Studies. Intended to make traditional university teaching obsolete, these were boxed sets that included three large posters, a bibliography, and a checklist that mapped out the patterns linking radical thought and avant-garde art that were pictured on the posters. Portraits and names of thinkers like Herbert Marcuse and Marshall McLuhan, along with provocative concepts and slogans—“Guttenberg galaxy,” “they became what they beheld”—were intended to encourage the students to think in non-linear ways so as to interact with, and interrogate, information from everyday life, from movies and television news, advertising and interpersonal relationships. The idea was that participants using this portable learning environment would come to engage in a direct way with the materials, unencumbered by the prejudices of teachers or institutions. In this interdisciplinary utopia there would be no textbook, no syllabus, and no final exam, and the faculty would include personages not actually in the room, figures like Marcuse and McLuhan, as well as Eldridge Cleaver and Jean-Luc Godard. Herbert Blau was so excited by the possibility of this that he actually began a campaign to entice Marcuse to leave UC San Diego and join the faculty at the new school.

Word of these revolutionary ideas soon percolated up to the trustees, who saw, with alarm, that the Disney utopia was being supplanted by a much more unsettling one, and demanded that any offer made to Marcuse be rescinded. At the same time, the faculty still teaching in the old Chouinard campus (now breezily identified as CalArts) were beginning to understand that there would be no place for them in a school fashioning itself around ideas rather than skills, around social issues rather than style. Although the new building was not yet ready, the new CalArts, the school of all the arts under one roof, officially opened in the autumn of 1970, using a disused convent in Burbank. In some ways, Villa Cabrini provided an ideal locale for an experimental school, consisting of dilapidated buildings and trailers connected to each other by arcades and courtyards, all surrounded by the hangars and wind tunnels where the Lockheed Corporation was developing the TriStar jetliner for Eastern Airlines.

A year of anarchic freedom ensued. To outsiders the place looked like a hippie colony, a place full of longhairs and dogs, children running free, and hand-held video cameras recording it all. Inside, it was a place of possibility. Although there were recognizable classes, the motivating idea was to create more informal spaces where artist teachers and their students discussed ideas and developed projects, most outside the traditional frameworks of art-making, projects that aimed to question the very institutional construction of art itself. As Corrigan said to a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, “We are developing the principle that all learning grows out of need and that puts responsibility on the students. The lines between the artistic disciplines have broken down. Painting now uses sound and structure, and has come down off the wall, for example.”14Alison Knowles placed the two concrete hobbit domes that made up the House of Dust on the broken tennis court, and made them available to anyone who wanted to use them as meeting place, performance space, whatever. Allan Kaprow organized a group of students to build wooden structures out in the desert, near Vazquez Rocks, working with Nam June Paik and Shuya Abe to videotape, but not record, the action. John Baldessari asked his students to invent an art game, concentrating on defining the rules of play in order to consider the constrictions posed by such structures on art and life.

Students attending a screening inside the House of Dust, CalArts, 1971. Image courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

* * *

This first year, in temporary housing and organized on the fly, seemed chaotic to some, creatively inspiring to others. Most acknowledged that it was a lot of fun, but some fretted about “learning outcomes.” Those with an improvisational approach to both art and life flourished. Here are some voices from that moment:

“Alright, sometimes it was more like an East African Bazaar than a school. It was a cacophony of sounds, from power saws, Moogs, cellos, and aircraft, and of disciplines from touchy-feely to Grotowski. But spirits were high, and in spite of the appalling lack of facilities, serious work was going on.” —Craig Hodgetts15

“But then I began to feel that teaching should have to do with the real experience of the teacher rather than only book learning or whatever you want to call it. And CalArts offered that. It offered positions to people who didn’t necessarily have a degree background. And so, since I had been traveling with the Fluxus group and had some opinions about new forms, I was able to jump in and enjoy teaching in Allan Kaprow and Paul Brach’s department.” —Alison Knowles16

“In 1970 Chouinard became CalArts; when CalArts took over, we didn’t know that practically none of the instructors from Chouinard would go to the new school. I’m one of the few people who bridged both places. In classes on perspective, we would make drawings of the new studios. Few other students had the opportunity to see what they looked like when they were just completed. I went from being at Chouinard, in the last year of its existence to CalArts, in the first year of its existence at Villa Cabrini in Burbank.” —Jack Goldstein17

“The first year I took mostly classes outside of the Art School. I took design. I don’t know if I took a class with John Baldessari then? Probably. Yes. Yes, I did. Design stuff. I did some music stuff. There was a class in Critical Studies, a class about witchcraft. Maybe that was a little bit later. So Cultural Anthropology, but it was like build your own cult and see what happens there. It was a fantastic place. There were really interesting people there, you’ve got the surfer poets and you’ve got the eggheads and you’ve got all these radical design people, and you had the conceptual artists, and you had world music. And I was sifting my way through these things and seeing what’s of interest to me, which is exactly what you’re supposed to do. And I don’t remember making stuff, that many things.” —Barbara Bloom18

“This was also a time when new schools were popping up, I don’t know how many a year. And there was this band of nomad-like students and teachers that would go from one hip school to the next hip school. And I think that CalArts was the next hip school to migrate to. And so they all descended. And there was just all this hype around, you know, who’s going to be the next Black Mountain College in alternative education, and, you know, blah, blah, blah. There was a lot of underground word about it. And I think every crazy in the world descended the first year. There was just utter chaos. But out of chaos, quite often there’s a lot of order going on. It’s order that one should distrust usually.” —John Baldessari19

“I was friends with a whole group of people who were kind of the Fluxus people. It was Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Nam June Paik, Serge Tcherepnin, who was a composer and was building the Serge, which was the other, more radical version of the synthesizer. They all lived in a house in the Hollywood Hills. And I hung out there with all those people. Emmett Williams, Nam June Paik—Nam June was fantastic. He would pretend he didn’t speak English if he didn’t want to do something.”—Barbara Bloom20

“It was very strange for him [Nam June Paik] to take this teaching job, and he didn’t know what to do. He said, ‘I don’t know how this is going to roll for me.’ Also, he always had understandable but crazy English. Paik was always struggling not only to be understood but to figure out what to do. […] I think he struggled with Shuya Abe to make a video class. Shuya Abe was a very skilled videographer so Paik kind of sat behind Shuya while he taught.” —Alison Knowles21

“We were coming off the highs of the 60s countercultural and experimental art movement(s) and there was a great deal of activity, but little structure. […] We were provided with tools and left to our devices to create and do what we wanted. It was sort of a giant arts laboratory. I taught a class on the Buchla 100 that began at midnight, which, at the time, didn’t seem all that unusual as there was activity going on 24 hours a day.” —Barry Schrader22

“It was a crazy time. I rebuilt the engine of my VW bus outside in the parking lot at Villa Cabrini, I got a Critical Studies credit for it. Just hung out with these people and there were all these discussions, it was quite a crazy year. People were swimming naked in the pool, trustees were getting upset. It was slightly chaotic but I met a lot of people, made some lasting relationships. Most of all I met people who had a strong influence on me.” —Stephen Nowlins23

“The place is an extremely disorganized place, and I mean, deeply disorganized. One normally expects that in an unstructured situation that the situation will generate its own structure. But in the schools at CalArts that has not happened. There has been a failure of leadership at the top levels.”—Dick Higgins24

* * *

While all this was going on, the Administration was locked in near constant struggle with an increasingly anxious Board. A couple of years earlier Haldeman had left for Washington D.C. to work for the newly elected Nixon, and Price had taken over as Chair, and as a result the Board was firmly in the hands of Disney people: relatives and employees. This very conservative group, who had deeply committed to an idea that they imagined would lead, at some point, to unknown but profitable synergies, were increasingly appalled at what they saw as the excessively libidinous and politically radical activities unfolding at Villa Cabrini. And they were finding it difficult to raise money: that year they were short $30 million on a $54 million goal to make the Institute self-sustaining. Outsiders looked at the Disney presence and decided there were plenty of deep pockets there; the insiders looked to the apparent chaos on campus and blamed that. Blau thought to appease the Board’s wrath by demoting Stein, making him the scapegoat for introducing Marcuse into the conceptual mix and formalizing the link between Eros and radical politics that the Disney people feared. For internal consumption he promoted the idea that the Critical Studies area was not collaborating enough with the other schools, and was encouraging excessive experimentalism, with classes that met on whim, or focused on joint rolling and other apparent absurdities. Then, early on February 9, 1971, a massive earthquake struck, damaging parts of the temporary campus, and closing the Freeway north to the new one, thus slowing construction. Months of uncertainty followed, with some Disney family members going so far as to open secret negotiations with officials at USC and Pepperdine University in an attempt to sell off the college and free themselves of an increasingly unwelcome burden. When that failed they decided to exert direct control over affairs on campus, fired Blau, and put Corrigan on warning. The second year was delayed by several months, officially because of construction delays, but also to accommodate the protests and meetings and interminable discussions triggered by Blau’s dismissal. The new campus finally opened in November 1971, and CalArts began again:

“Well, the whole idea was to raise the question: what do you do in an art school? And you say, ‘Well, what courses are necessary to teach?’ and that is a question begging in a way, because you can say, ‘Well, can art be taught at all?’ And, you know, I prefer to say, ‘No, it can’t. It can’t be taught.’ You can set up a situation where art might happen, but I think that’s the closest you get. Then I can jump from there into saying, ‘Well, if art can’t be taught, maybe it would be a good idea to have people that call themselves artists around. And something, some chemistry, might happen.’ And then the third thing would be that to be as non-tradition-bound as possible, and just be very pragmatic, whatever works. You know, and if one thing doesn’t work, try another thing. My idea was always you haven’t taught until you see the light in their eyes.”

—John Baldessari discussing CalArts with Christopher Knight, Archives of American Art25

CalArts Convocation, Main Gallery, Valencia, 1971. Image courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Although the building had been no secret, when it became the actual home of the new school, faculty and students recoiled in dismay. A massive, blind hulk looming over the asphalt fields of a sprawling parking lot, the structure looked more corporate headquarters than experimental art school, certainly not friendly in the way the old convent had been. Knowles remembers people calling it the “Dow Chemical Center,” while Hodgetts thought it was “simultaneously suburban and extraterrestrial,” lacking character, but also appearing strange. But if the exterior was inappropriately monumental, the interior seemed unworkable—Paul Brach noted in an interview in 1971 that, “the architect had planned the whole building long before Bill Corrigan, Herb Blau, myself, Mel Powell, any of the top management, were hired.”26A lot of predesigned spaces proved to be unsuitable for the curricular ambitions of the faculty. And some spaces were just wrong: for instance, the Dance School found their studios dark and small; and Brach, perhaps recognizing that painting would not hold the central position it traditionally has in art schools, ceded them two large, north-facing rooms. Worse than this kind of misalignment, the interior maze of wide corridors and closed doors, cut off from natural light, simply shut down the open-ended possibilities that the Villa Cabrini courtyards and arcades had promised. Those spaces had been activated by the experimentalists that Kaprow had persuaded to join the faculty, the group charged with creating the buzz of the new. The new building imposed a new order: individual faculty were free to create their own curricular programs, but interaction between faculty and programs became more difficult.

Throughout this period of flux and change, Brach took responsibility for making sure the more mundane elements of an art school curriculum were covered. In a 1971 interview he is clear about the separation between inspiration and reality. “When we started the school, we started to believe our own rhetoric that there was some hope that we could create a kind of community in which to make art, etc. But, you know, when one member of the community has to pay $2,500 to belong to the community and another person is paid $15,000 for being part of the community, the rhetoric gets very confused. So it is a school, and it has professors, and it has students. We don’t call them professors, we don’t have various grades, etc., but we are now wondering about what maximum and minimum teaching hours should be. It’s going to be a very good, a very, very lively, terrific art school. But to talk community of the arts, with its communitarian implications, I think is a metaphor. We’re a very good school with first-class possibilities.”27To ensure this was the case he kept a small group of instructors from Chouinard, including the venerable painter Emerson Woelfer and the kinetic sculptor Stephan von Heune, to ensure a sense of continuity on studio practice. But he also brought two hot young painters from New York, stars of the 1969 Whitney Annual, Allan Hacklin and John Mandel. And he and Kaprow co-taught an art history class. So in many ways there remained a core of instruction centered on painting and the European tradition. The teaching method employed by these people also seems to have been modeled on east coast schools, with an emphasis on public degradation. Eric Fischl remembers the critiques as being like thrown into a Roman arena: “It was a blood ritual of some kind where the whole thing was to inflict as much pain on a student as you could because if they cry, if they felt pain, it meant the thing they were doing was meaningful, it was alive.”28

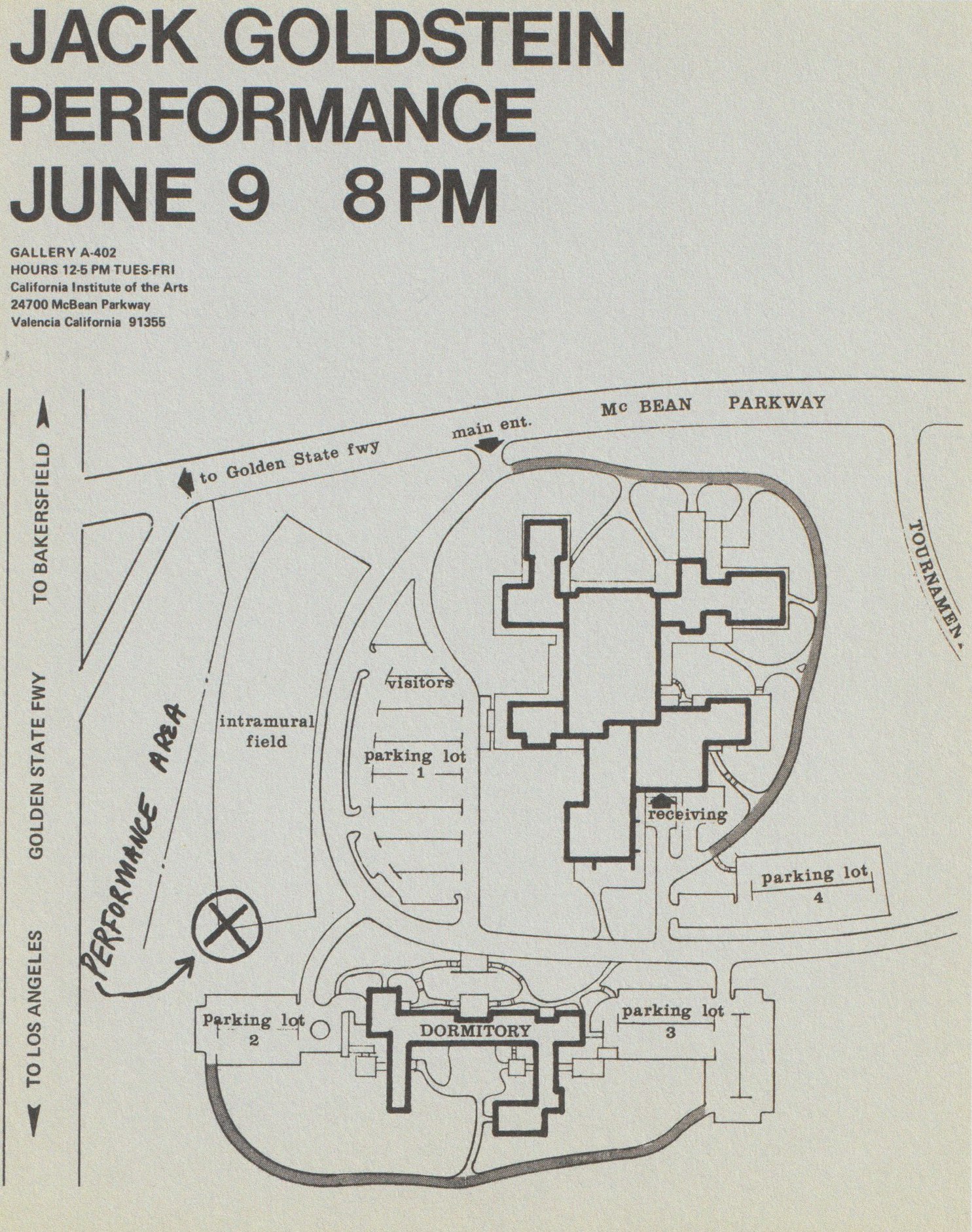

Flyer announcing Jack Goldstein’s on-campus performance at CalArts. Goldstein had himself buried on the intramural field, with a red light showing that he was still breathing. Image courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

John Baldessari had also been hired as a painter, but in the summer before starting work at CalArts he had made a work by cremating his extant paintings, and redefined himself as a conceptual artist. He talked to Brach about wanting to teach something different, and offered up the idea of a “post-studio” class that would frame a discussion of the new attitudes to art that were taking shape in New York and across Europe. The idea was to provide a theoretical and historical framework for understanding these new trends in art, within a generously discursive environment that would include learning about a wide range of artists while also talking about the work the students in class were attempting. As Barbara Bloom described it, being in his class felt much more like hanging out with an older and smarter friend: “I didn’t even know he was teaching. He hung out. You know, like you said, you had a cigarette or something. You hung out, you talked about stuff. He had friends of his come in, they presented what they were doing. You talked about it. You went out for dinner. He suggested you might want to read a book. You read the book. We talked about it. There was no hierarchy there. He was insanely generous. I mean, I don’t know how he did it for many, many years. And he was a phenomenally generous teacher. And there was no discussion of when are we going to call it art. And if there was a discussion, it was a discussion about that. You know, how do we know when we call it art? That’s what his whole thing was. Look here, look here. It was a philosophical practice.”29

During the first year Miriam Schapiro, Brach’s wife, became increasingly troubled by the heavily male presence on the faculty and began looking around for a remedy. She heard that there was an interesting feminist program being run by Judy Chicago at Cal State Fresno and persuaded her husband to drive north to check out their year-end exhibition. Liking what they saw, they invited Chicago to join the CalArts faculty and bring her program, and some of her stronger students, with her. The Feminist Art Program (FAP) began in the fall of 1971, and after an orientation meeting it was decided to move off campus, as the new building was just too oppressive. Someone found a run-down house in Hollywood, and thus the Womanhouse project came into being.30Paula Harper, a young feminist art historian from Stanford, was hired to help establish a visual archive of women’s work, with help from the students. And the group began meeting regularly in what Schapiro described as “consciousness-raising sessions,” leading, through emotionally wrought investigations of individual trauma, to the creation of an ambitious, collective installation using all the rooms of the house.

There was a very real polemical antagonism between these two groups. Chicago was aggressively dismissive of Baldessari and his ‘boys,’ and their obscure intellectualism; the Post-Studio group, in turn, found the feminist work unconvincing, both stridently obvious in content while prolix and self-indulgent in formal terms. But despite that, there was a shared radicality of purpose. Both groups were establishing a new and more relevant history—Baldessari brought back catalogues from his travels to Germany to prepare for documenta, and Chicago made slides of women’s art she discovered around the US and Canada. Both were also searching for new and more productive ways of discussing how to understand, navigate, and develop that new history. From the student’s perspective, David Salle described a situation of increased awareness: “Once a certain attitudinal threshold was crossed, best expressed by the catchphrase ‘Anything can be art/art can be anything,’ you had to be alert—you never knew where an idea was going to come from.”31Whereas Schapiro talks about it from the perspective of the instructor: “What kind of a teacher can I be? Ultimately I accepted myself as a facilitator. My growing philosophy of education was based on the idea that they had as much to tell me, as I had to tell them. The only difference was in our ages—that indeed if I had lived longer than they did, which I had, I had more experiences perhaps. But they might have had denser experiences.”32

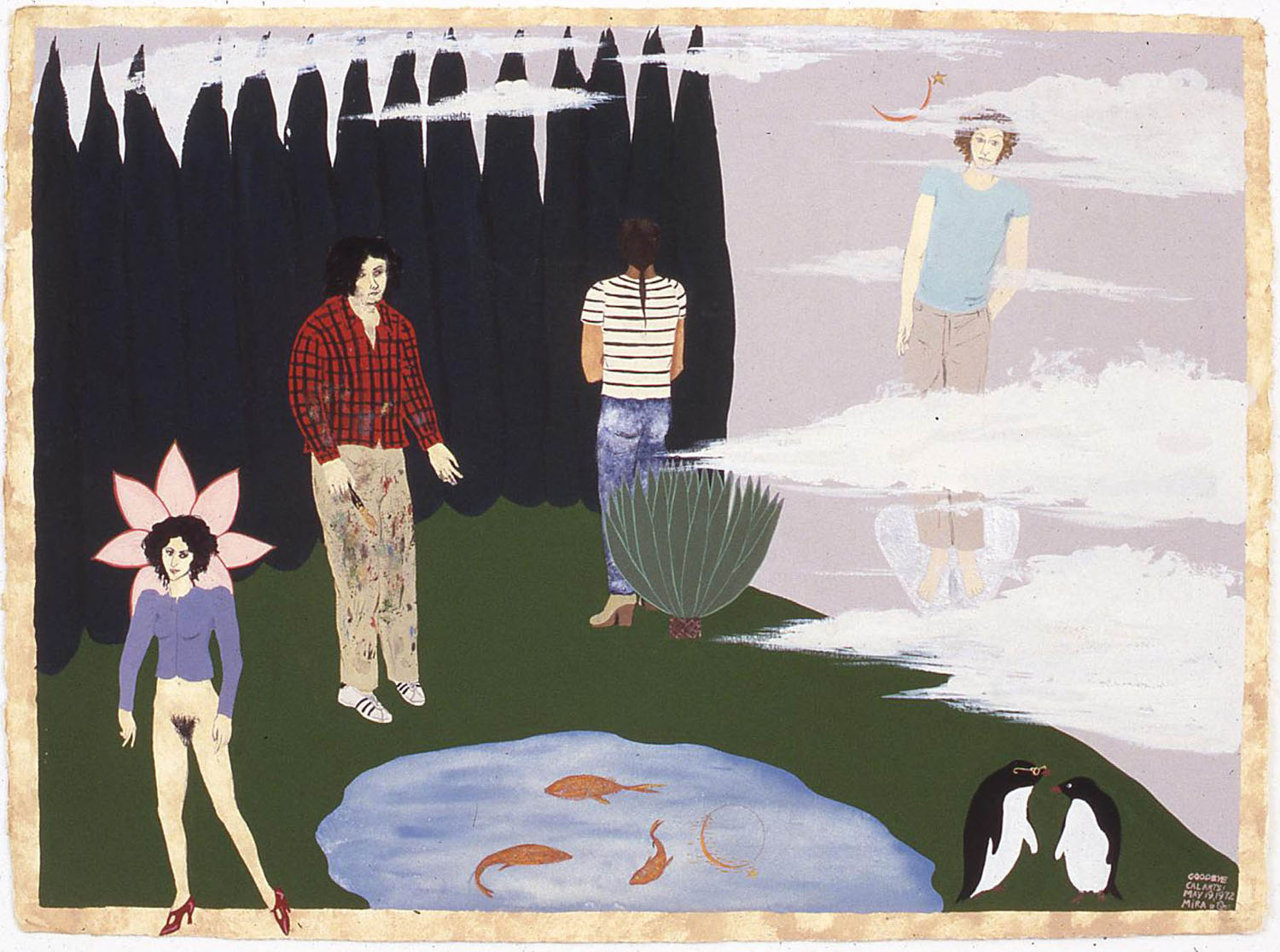

Mira Schor, class assignment, Feminist Art Program, CalArts, 1971. Image courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

Mira Schor, “Goodbye CalArts,” 1972. Image courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

In a sense Kaprow’s non-judgmental avant-gardism provided something of a bridge between these opposing camps. He had been struggling longer than most to find new ways of thinking and talking about art, understood the stakes, and the cost. If the value of art could be found anywhere, then teaching it had to be about encouraging an attitude of openness, and as Suzanne Lacy said, “Allan’s teaching methodology was cool, discursive, anything was possible, everything was interesting to discuss. […] I think he was struggling with how to handle not only the move to the West Coast but the move from the grand, expressive gesture to a different kind of concern. […] What I learned from him was not only that there is always an intimate psychological connection but also a level of self-investigation that goes on in most art.”33But while the artists variously associated with Baldessari, Chicago, and Kaprow were finding productive ways to process societal change and invent meaningful interventions within the realm of art, the more restless minds of the Fluxus artists were finding that the new Institute was not as utopian as promised. Some sort of framework for learning was being requested, a sense of purpose required. Worse, the fortress-like building with its subterranean maze of closed doors became a literal manifestation of a Kafka-esque hell, closed off to spontaneity. Soon they were all moving on, and indeed the three years between 1972 and 1975 saw most of the early participants in the CalArts experiment leave—Nam June Paik, Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles, Ravi Shankar, Judy Chicago. Robert Corrigan was fired in 1972, temporarily replaced by William Lund, a WDP executive also married to Walt’s adopted daughter, Sharon, who worked diligently to keep the trustees focused on the future rather than fretting about behaviors in the present, and who gave the deans further authority to build their schools. He appears to have been relieved to hand over the job to Robert Fitzpatrick, a professor of medieval French literature at Johns Hopkins, who became the second president of CalArts in 1975. This brought a formal close to the animating vision of the first years, which called for a new social formation in which, in Marcuse’s abstract language, “a new type of men and women, no longer the subject or object of exploitation, can develop in their life and work the vision of the suppressed aesthetic possibilities of men and things—aesthetic not as to the specific property of certain objects (the objet d’art) but as forms and modes of existence corresponding to the reason and sensibility of free individuals.”34In an interview a few years later, Fitzpatrick said, “The trouble with utopia is that it doesn’t exist. And then there was this dream of the perfect place for the arts, with all the disciplines beautifully mingling, every filmmaker composing symphonies, every actor a perfect graphic artist. Sure, it’s a great idea as far as it goes. But nobody noticed that each of the arts has its own pace, its own rhythm, and its own demands.”35The ambition now was to be a very good school with first-class possibilities.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this essay was published in “Where Art Might Happen: The Early Years of CalArts,” eds., Philipp Kaiser and Christina Vegh, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover, 2020.