A Situation Where Art Might Happen: John Baldessari on CalArts

by Christopher Knight

From an oral history interview with John Baldessari, conducted by Christopher Knight at the artist’s studio in Santa Monica, California, April 4–5, 1992. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

Portrait of John Baldessari. Courtesy of the California Institute of the Arts Archive.

CHRISTOPHER KNIGHT: Can you describe the program at CalArts? Because it was relatively raw then.

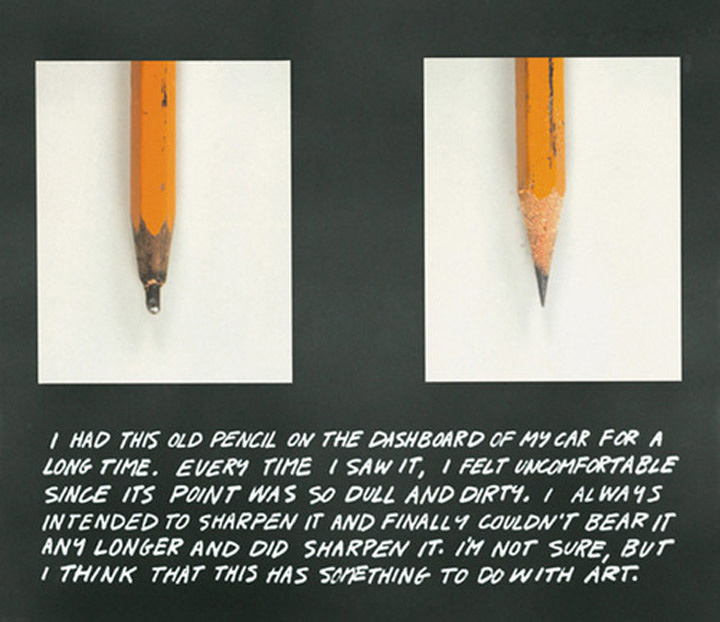

John Baldessari, The Pencil Story, 1972-3. Color photographs, and colored pencil on board, 22 x 27 ¼ in. Courtesy of John Baldessari.

JB: Basically, I tried to give them sort of a brief history of contemporary art, so they could see that the things I was interested in didn’t come out of the blue sky—that there was some continuity to it all. So a liberal use of slides and overhead projectors instead of books. And since I was on the road a lot in Europe and New York doing shows, I would bring back catalogs, magazines, and talk about the stuff I’d seen. These students had probably the quickest access to information of any art school in the US, I would wager. They didn’t have to wait for it to come into the magazines. And plus the visiting artists. I would have at least one or two a week talking there. And field trips. But not necessarily art related, you know: going into the things that introduced them to culture in the broadest sense, like going to Forest Lawn, or the Hollywood Wax Museum, or what have you. And a lot of times just anything to get out of the studio. One of my tricks was that we’d have a map up on the wall, and somebody would just throw a dart at the map, and we would go there that day. [laughs] They could take their video cameras and still cameras, and do whatever they wanted in just staying out there. Try to do art around where we were.

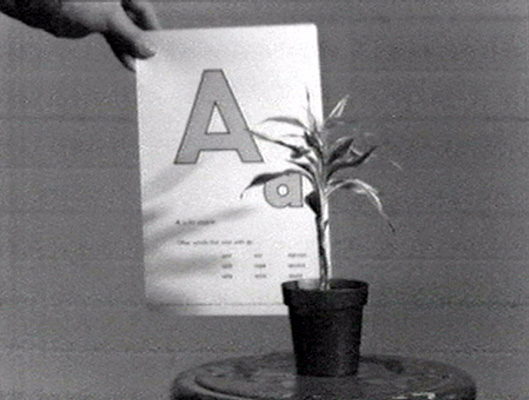

John Baldessari, still from Teaching A Plant the Alphabet, 1972. Black and white video, 19 min. Courtesy of John Baldessari.