A Story about Civil Disobedience and Landscape: Interview with Andrea Bowers

by Thomas Lawson

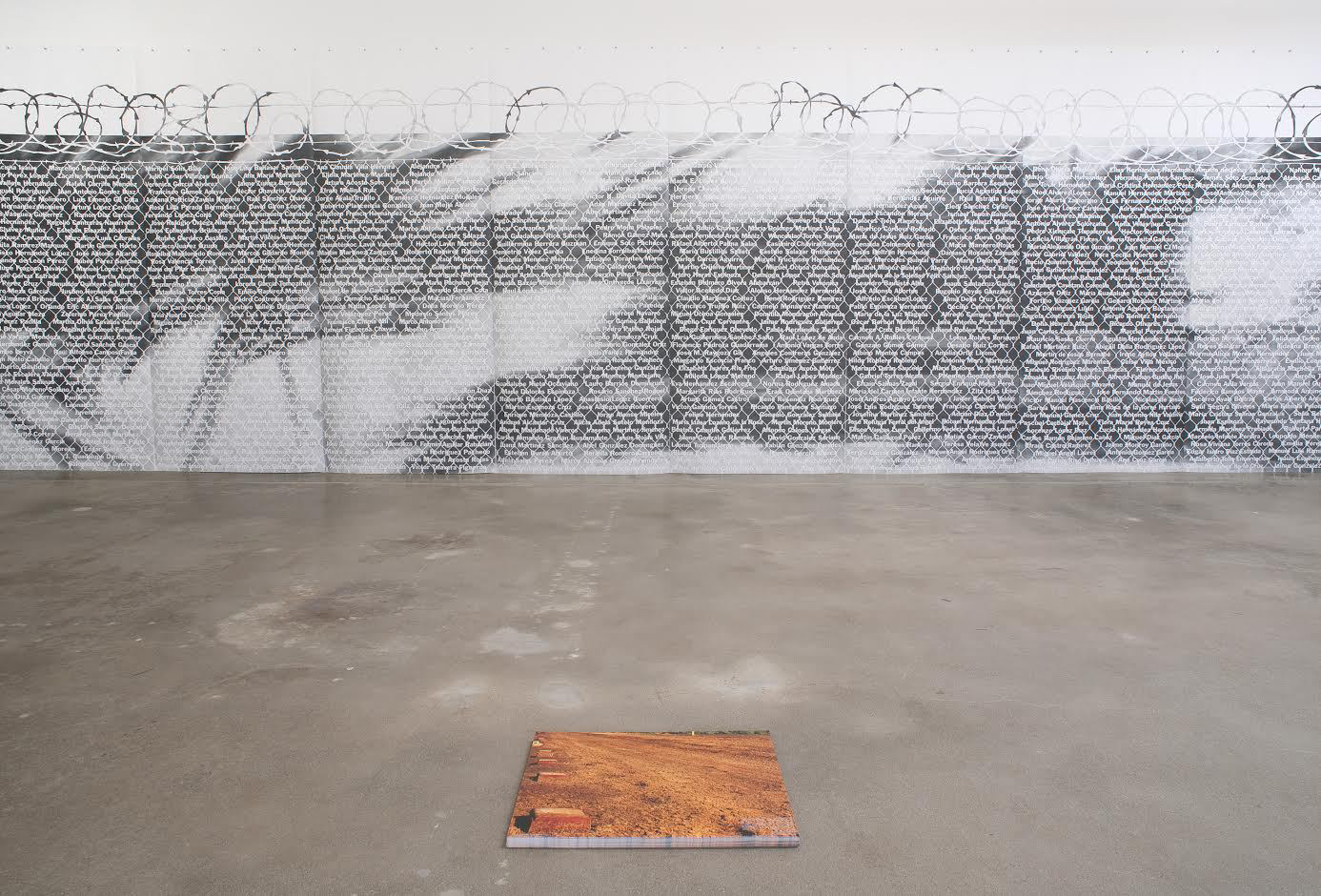

Andrea Bowers, No Olvidado – Not Forgotten, 2010. Graphite on paper, 23 drawings, 50 x 120 in. each. Photos: Robert Wedemeyer. All images courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

This interview took place in the kitchen of Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects on a July day near the end of the run of Andrea Bowers’s exhibition “The Political Landscape.” The show consisted of two large projects and a suite of small drawings. The first project, which one encountered upon entering the gallery, was No Olvidado (Not Forgotten), a mural-like drawing consisting of 23 ten-foot-high panels that listed the names of people who have died in the attempt to cross the Mexican-American border. The second was a single-channel video projection, The United States v. Tim DeChristopher, which examines DeChristopher’s disruption of a government auction of wilderness land for oil and gas exploration. Operating as a lever or hinge between these two oversize images, respectively of an enclosing, claustrophobic wall and of a vast, somewhat forbidding landscape, was a line of small, meticulously rendered drawings of individuals holding signs protesting the recent Arizona law giving local police the authority to question anyone they suspect of being an illegal immigrant. In these works Bowers was using well-established representational modes to open up a wide-ranging discussion of the politics of landownership and control, and to implicate the landscape tradition in art as part and parcel of that. As the press release for the show notes, one of the earliest functions of the landscape picture was to display owned land, and Bowers turns that project on its head to reveal the abuse of ownership that has too often been the reality in the American West.

Thomas Lawson: Before we begin talking, I just want to say that the show is stunning, and requires considerable time to sort out. The first piece, the memorial with the names, is kind of overwhelming, both grand and very intimate in its effect. It is also oddly light filled—the gallery is bright, there are patterns of light and clouds drifting over the names inscribed on the wall—it almost seems uplifting until the weight of the names sinks in. And then we step into the next gallery, which is in total darkness for the projection, and witness this strange alteration between an extreme close-up of a talking head, and you marching back and forth in a very barren and cold-looking landscape. It takes a while to sink in that it is all about various governmental misuses of variously inhospitable, but fragile, desert lands. We could start by saying that the show is about the American West, right?

Andrea Bowers: Yes! It’s the contemporary American West, and the abuse of power—which is what the depiction of landscape has always been about.

TL: And in fiction and film the American West has been presented as the locus for an endless struggle for power and control of the land and its resources.

AB: I looked at a lot of those photos [Timothy H. O’Sullivan, H. H. Bennett, Darius Kinsey, Edward Weston] that were taken when the American government initially surveyed the West. They sent all those photographers on explorations of the West, and they took iconic, sublime photographs. My idea was to recontextualize these images in some way to reveal a historical lineage of colonialism embedded in all those sublime photos.

TL: Are you doing this in some way to effect a change of consciousness in your viewers? Do you have hopes of engaging people in working toward some sort of action after seeing the work?

AB: I don’t think I’m directly attempting to bring about social change. I just see myself as bearing witness or documenting these people [the names in No Olvidado] because I think they’re underrecorded. My way of doing that is through art, because that’s what I’m good at. It’s also just about … It’s really about me and figuring out what I believe in and where my limits are. It’s really about the reeducation of Andrea. I grew up in an apolitical Republican family. So, it’s very much about that.

TL: This was in Ohio, right?

AB: Yeah! In Ohio, the political battlefield state. Now you’ve got 24-hour, seven-day-a-week news. It’s all really, really fast, sound bite sound bite sound bite. What can we do as artists? The art world is really slow. One thing I think we can do is tell an in-depth, long story. I think that art can be a kind of amazing history vault; things reach out. So it’s pretty simple. I’m telling stories that you won’t find on a 24-hour-news-cycle channel.

TL: I wanted to talk a bit about how you do that, how you actually make the work, not just the idea, but how you put it together. And because I think they offer an interesting insight into your process, I’d like to begin with the group of little drawings, and how you went about making them.

AB: Okay, well, first I want to say that a lot of what I do starts with a photograph. For these drawings I shot the pictures myself, I didn’t find them.

TL: So you went downtown to join the demonstration.

AB: Yes, on May Day in 2010, downtown Los Angeles, and it was a really loud and contentious march. That’s when the “show-me-your-papers” law had just been announced in Arizona; people were really fired up. I just went to the march, and along the route asked people if I could photograph them with their protest signs.

Andrea Bowers, Study from May Day March, Los Angeles 2010 (Stop Ripping Families Apart), 2010. Graphite on paper, 9 x 12 in.

TL: And they posed themselves?

AB: Yeah, it’s not very complicated. They’re walking, part of a huge crowd of thousands of people, and I’m like, “Hey! Can I take your picture with you holding your sign?”… but I’m a terrible photographer, I never passed a photography class. I failed or dropped out every time. But I realized that the whole process is important to me, and that even if I could find similar images in an archive somewhere, I actually prefer to draw from my own bad photos. I can remember the moment I shot them.

TL: And are they color photos or black and white?

AB: I shoot color, and usually if it’s a color photograph I draw it in color. But in this case I decided to do them in black and white, to have a relationship to the drawing installation. I thought that it would be interesting to have to deal with my really bad photographs; they were totally backlit, which left most of the faces dark, with crazy light patterns on them. There’s a similar light quality in the big drawings.

I still work from slides; I think that slides are so much richer than a video projector. I know I’m going to have to use a video projector eventually. It’s important in all my work that the viewer be clued in to the fact that all my imagery comes from a documented source, and is not an invention of my own subjectivity. I’m becoming more and more interested in thinking about ways to compose that are systematic, in order to question the Romantic myth of the artist. I have this belief that there’s a huge difference between a photograph and a drawing. People just read them differently. I think photographs are much more cold in a certain way, or documentary. I think I seduce people into the imagery with the craft of the drawing. And at times the drawings function as agitprop.

TL: So it’s through your labor that you get people to look at the political content?

AB: I mean, you understand this idea, I think I might have learned it from you—that there are certain ways of making art in a vernacular that everybody understands. I think drawing is populist in a way that almost everybody identifies with it, particularly when it is labor-intensive and skillful.

TL: And maybe they like it also because it’s realistic, right? They can feel some sort of comfort that they know what they’re looking at.

AB: Yeah, but I get really criticized for that type of illusionism.

TL: Well, it’s not a 20th century avant-garde tactic particularly, although you contextualize these drawings with plenty of other activities that do seem more in line with avant-garde practices.

AB: That’s true, like the series of events and conversations occurring during the show. And the thing that I hoped would happen was that these events would broaden the viewing community. It did, particularly with the Latino community, because of the subject matter of immigration rights. I thought—I assumed—that it would be the list of names that the majority of people would identify with, and surprisingly it was not. Those small drawings were a last-minute addition, and yet people would come in and they would have their pictures taken with them.

TL: Wait a minute; they were getting their pictures taken beside the drawings of people who’d had their picture taken by you?

AB: Yeah. It was amazing—it was so amazing. That was the work that just reached out emotionally; they identified with the images. There would be whole families in the gallery and they’d have their kids stand underneath the drawings. First they’d take close-up pictures, and then they’d step back and shoot the whole family posing with the drawing. I had no idea the drawings could function that way.

TL: That’s interesting, because when you walk into the gallery, the showstopper, the thing that grabs your eye, is the huge, multipanel drawing with the names.

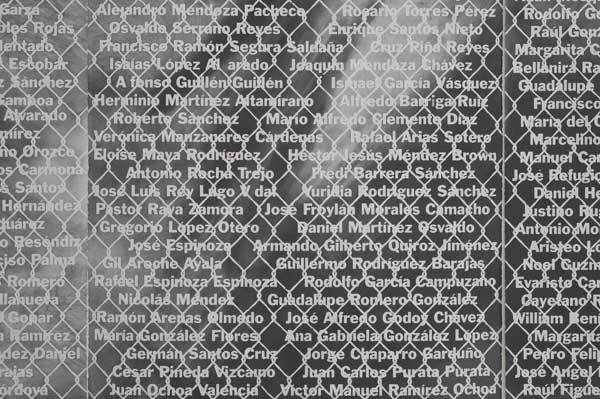

Andrea Bowers, No Olvidado – Not Forgotten (detail), 2010. Graphite on paper, 23 drawings, 50 x 120 in. each.

AB: Yes, it’s a hundred-foot drawing.

TL: And it is set up as a memorial, it’s a very grand piece. Let’s talk about it. Since it is monumental, it presumably required a different way of working?

AB: Right. I worked with a graphic designer and several assistants. It resulted from a conversation with an activist, Enrique Morones. He founded an organization called Border Angels. They started off in I think ’86, providing water and blankets to people crossing the border.

TL: And many die in the attempt—are they killed out there in the desert, or do they die from exposure and thirst?

AB: It’s both, but in many cases nobody knows. A lot of people die from dehydration or temperature, but there are also people who are killed. So Enrique collects names of anyone who dies migrating from Mexico to America. He actually has about ten thousand names. He finally admitted that the group of names he provided to me, a list of four or five thousand, is only up to the year 2000.

I’ve always been making memorials in one way or another, but memorials that I thought would never be made, or memorials that were kind of impossible to make. I’m fascinated by the Vietnam Memorial in DC, and how listing names functions in general. An important part of what I do concerns this documentary-type collection of information. But then there is the formal aspect, the translation of that information into form. For years I’ve been working with another drawing method that acknowledges the photographic source, not as detailed as in the photorealistic works. For these I scan an image or text and then turn it into vinyl, and use the vinyl as a template. It’s a method that allows me to work on a larger scale … it enabled me to make these twenty-three drawings, 10 feet by 50 inches each.

I worked with a graphic designer to place the names because I wanted them to function as individual units and yet feel interwoven in the chain-link and razor wire. It was tricky finding the right font and the right thickness of chain-link, and also finding images of barbed wire that didn’t look cartoony when you turned it into more of a pattern. I worked for literally a couple of months with a designer and then printed them out as large Xeroxes to figure out the scale. I tried different sizes and finally decided they needed to be on sheets of paper at least ten feet high.

Once the cut vinyl was on the paper, I brushed the ground in powdered graphite using a five- or six-inch brush, so it was very gestural, and any remaining white areas we would fill in with shading, in a medium gray or light gray. And then I had to copy the gestural mark making in the shading to create a transitional pattern from one sheet to the next.

TL: As you describe that process I am thinking about the fragility of it all. I mean it’s … in terms of doing this monumental work but making it out of paper and graphite, which, is so superfragile and hard to handle.

AB: Yeah, a disaster to handle. They get smudged constantly. They’re not pristine.

TL: But I think the smudges and everything adds to the humanity of it.

AB: Right. I just have to tell this one little story. At one point, this little girl—she was maybe four—ran up to one of the drawings. She was wearing a perfectly handmade white dress with all this beautiful embroidery, and she ran up and rubbed her whole body on one of the drawings, and then she slid down three of them. So there are four drawings that are just like shhhhhrrrrr. It’s amazing, just part of the work now.

TL: Is that audience participation?

AB: Yeah! They call her the tornado girl at the gallery, because she just spun around and hit all the white walls too. She was covered in smudged graphite. Her mother came up to me almost in tears, and I was like, “It’s okay! It’s really okay!” But, you know, it is what it is. I was determined that these large drawings function as a setting for social activity. I thought about it as this really fragile situation, and the drawing being this personal thing that I would do. Most official monuments are made of stone and marble and bronze, they are sanctioned by the government, they get a specific place. There’s just something that is so psychologically fragile about border regions, and so—I guess because I lived in Tijuana for a while, crossing the border never made sense to me. It was just so wrong, because as an American citizen I could easily cross, while so many other people couldn’t.

TL: The ecology down there is so fragile, and having this ridiculous intrusion of a fence…

AB: And until recently, there were holes in the fence; it was more porous. Many artists my age who are from the border region talk about playing along the fence, going from side to side. It’s so ridiculous because we have millions of undocumented workers in this country. The jobs are here, or they wouldn’t come. I saw these amazing signs at a recent protest. People were holding images of the caution sign that’s along the freeway in San Diego, it [the caution sign] shows silhouettes of a family crossing the border. Each protest sign was recontextualized with the addition of a word like dreamers, opportunity, education…

TL: And it’s just part of the human way that people move. They move in waves. For various reasons: the economies, the climates, politics. I think we’re always in flux. And to try and make a barrier is almost…

AB: Yes. I wanted to create the opposite of this really hard, solid structure because I am suggesting the opposite of the American government’s border policy. That idea of building better fences. I wanted it to be a confusing space. You couldn’t read: foreground, middle ground, background. Everything is in flux in terms of the perspective.

TL: Right, and the light—when the light shines across it. The smudge is perfect, the girl’s—

AB: I know! I tried to clean it up at first. I’m a control freak, you know? And then I realized, “Okay, conceptually this is great. But as a craftsperson I’m dying inside.”

TL: How are the names ordered across the face of the piece?

AB: It’s just the way that Enrique [Morones] had them listed on the website, organized by the state where the person died.

TL: It’s a very emotional set of information…

AB: It becomes very personal. And you know, I’m just getting to know Enrique. We’ve been working together for two years, and I think that he’s beginning to trust me. He didn’t see the work until he came to the gallery a week after the opening, and he was really happy. Then he started trusting me. I asked him to speak on the first Saturday of the exhibition, and it was overwhelming because he could point to names and tell you how they died and who their families were. That was very powerful. I didn’t expect that.

TL: That is fantastic. Let’s try to navigate our heads into another space, the Tim DeChristopher piece. It seems so different in some ways. How do you get involved in a new subject or a new project?

AB: I read and I listen to alternative media. It’s usually a relationship between a story that pulls at my heartstrings and that I’m politically compelled by.

TL: So you’re working on the names piece, say, and you hear a story about the Bush administration’s plan to sell off land bordering Arches National Park [among other public land parcels] in Utah?

AB: Well, it was kind of about the same time. I think it was 2008 when DeChristopher bid on all of that land in Utah. Bought it illegally with no money.

TL: Well, I guess he didn’t buy it, right?

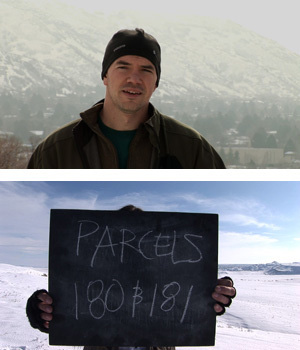

Andrea Bowers, stills from The United States v. Tim DeChristopher, 2010. Single channel HD video, 16:15 min.

AB: He bought it but he couldn’t pay for it. He bid on 22,000 acres of land at $1.85 million. He was so compelling because he’s the first activist I’ve ever done an interview with who is so pessimistic. Most of them, especially the environmental activists, are superoptimistic. But he is getting into survivalist mode, to deal with climate change.

TL: It’s a pretty great story. And then you contacted him?

AB: Yeah. I did the research to track down his email. I regularly correspond with different activists, so I can usually call one of them up to help me get in touch with another.

TL: It seems that when we’re talking about the formal aspects of studio practice and all that, there is a huge work difference between making drawings and making videos. It seems like a different—

AB: Yeah, except there’s this evil similarity. Sometimes I get so obsessed, I’ll tape off a photograph down to an eighth of an inch and copy it as an abstraction. And when you edit, there are 24 frames per second. So I can have 24 still images, right? For every second!

But there is a crucial way that the video, for me, is different from the drawing.1It’s monotonous to do that drawing, and the video projects provide a more direct engagement. People always ask me—you totally understand this—if there is some sort of sublime experience while I’m drawing. No!

TL: No. You go in and you rev yourself up to do some task.

AB: And you’ll spend a lot of time in avoidance—I’ll scrub my tiles in my bathroom with a toothbrush before I get that drawing started. And it’s exhausting, because there’s a thought process, a weird concentration. You’re not really doing that much, but you’re confronting decisions all the time.

TL: I do understand that very well, but with the video work, what I find difficult is to come to terms with the movement…

AB: Yeah, I’m not as good at that. I’m much better at 2-D. When I was shooting the landscapes I was dealing with this grand panorama, and the camera really sucks at capturing it. When you’re there you have much more of a sense of depth and scale.

TL: You’re surrounded by something.

AB: You can’t get that on a video camera, an experience of space through your body, it just really flattens it out. So I wanted something that’s a little more involving for the viewer, because otherwise you have to just speed up the footage to see the clouds move or the birds fly by or whatever. I really wanted a sense of scale—of how much land he’d bought. And then, of course, I was in the land of Earthworks artists. Thinking about Smithson, I spent two days before traveling, getting all wound up and annoyed with the macho boys, even though I love the work. I looked at a lot of photographs, the stills of those guys, out there with their shovels, wearing bad cowboy boots. I just wanted to make a little fun of their pretensions.

TL: But Tim is kind of macho too, at least in the video.

AB: Yeah, that’s always kind of a problem for me, you know? All of these environmentalists are pretty much macho men. But I think it’s a much more heroic gesture to leave the land untouched rather than dig it up with big bulldozers. I thought another counterbalance was to have him speaking, and me doing the walking. I’m still trying to create an alternative to the representation of women in the history of art and advertising. I try to present myself in action. Simple! He is an activist who actually succeeded. There aren’t many of them. It’s a story about nonviolence, about civil disobedience. It’s a story about landscape.

TL: Earlier you were saying that one of the ways you brought a different dimension into the work was by creating events in the gallery, and you did separate events for this piece, again inviting people who don’t normally go to art galleries to come and see and discuss the work.

AB: I was trained to believe that galleries were compromised institutions. I have a lot of guilt associated with my participation. But in teaching public practice these past few years I’ve been thinking about the gallery as a community center. We just need to expand the audience. I did these events almost every Saturday during the show, and the funniest thing is that the regular art crowd was petrified to walk in the door because they’re so used to the gallery functioning in a certain way. I didn’t plan on that happening either. I had to literally stand at the door and kind of whisper or usher people in and explain that it was okay and they could walk around and they could have some food and they could sit and talk to people. But in the end, it was good. Some of the events were fund-raisers, and we were able to raise money for both DeChristopher and Border Angels.

TL: You’re a fund-raising machine.