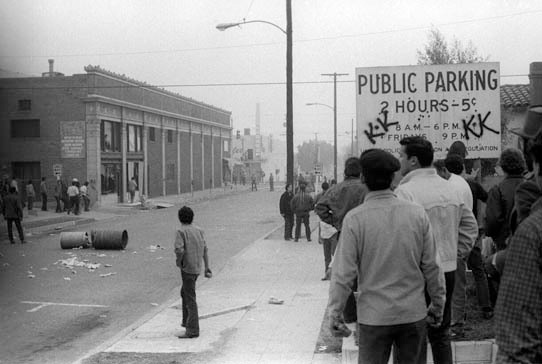

Victor Aleman, Just Before the Gunfire, 1971. Photograph. Courtesy and copyright the artist. All rights reserved.

I recently visited the Mexican Cultural Institute in downtown Los Angeles to see the 40th anniversary commemorative exhibition on the Chicano Moratorium, an anti-war movement that organized protests in East Los Angeles from 1969-71. The protests were marred by rioting and historically marked by the violent death of Los Angeles Times journalist Ruben Salazar, who was fatally struck in the head by a tear gas projectile fired by a Los Angeles County Deputy Sheriff. In the exhibit, I found myself drawn to a photograph by Victor Aleman. I was riveted by the personal significance of his grainy black-and-white image depicting several police officers and protesters on a familiar street corner in East L.A. I have often made reference to this life-altering event but had never seen an image that captured the dangerous scene from a vantage point so close to my own.

In the 1960s I witnessed an infinite array of the extreme aspects of urban life and death. I became involved with the Chicano Movement as a student leader of the 1968 East L.A. Walkouts and was the editor of

Regeneracíon, a Chicano literary and art journal. East L.A. was placed under excessive police control during the next few years in a manner that closely resembled a military occupation. Chicano youths were routinely rounded up, harassed, beaten and arrested, without regard to their constitutional rights. I had firm beliefs regarding my activist role as an American citizen who sought change from my cultural perspective. Being shot at by numerous riot police strengthened my sense of purpose.

On January 31, 1971, nearly a dozen uniformed Los Angeles County Deputy Sheriffs lined up across the intersection of Whittier Boulevard as several hundred young people marched peacefully along Arizona Street in protest against ongoing police intimidation and brutality in the Chicano community. The demonstration became eerily theatrical as deputies raised their fully loaded shotguns while the unarmed protesters approached the boulevard. The deputies suddenly began free-firing their weapons many times and scores of wounded people fell to the asphalt while many others scattered for relative safety. At least one individual was killed.

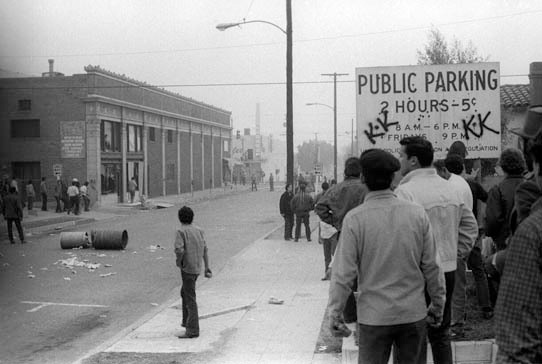

I was among the lucky youths who were spared. I walked away from this extreme violation against humanity transformed and intent on finding an alternate method to confrontational street politics. It was soon after this period of violent history that the collective Asco (Spanish for nausea) evolved. Artists Willie Herrón III, Gronk, Patssi Valdez and I performed ephemeral actions that we documented with photography. In 1974, I photographed Asco performing

First Supper (After a Major Riot) on a traffic island on Whittier Boulevard and

Instant Mural where Patssi Valdez was taped to the wall in the same location that appears in Aleman’s photograph above.

Reverberations from that charged era persist into the present as images and eyewitness narratives are presented to a contemporary audience in an effort to amend history. Aleman’s photograph encapsulates the chaotic pivotal moment, which changed the course of my activism and artistic practice.

Asco, Instant Mural, 1972. Performance. Pictured: Gronk, Patssi Valdez, and Humberto Sandoval. Photo: Harry Gamboa, Jr. Courtesy the artists.