Andrea Bowers’s History Lessons

by Jill Dawsey

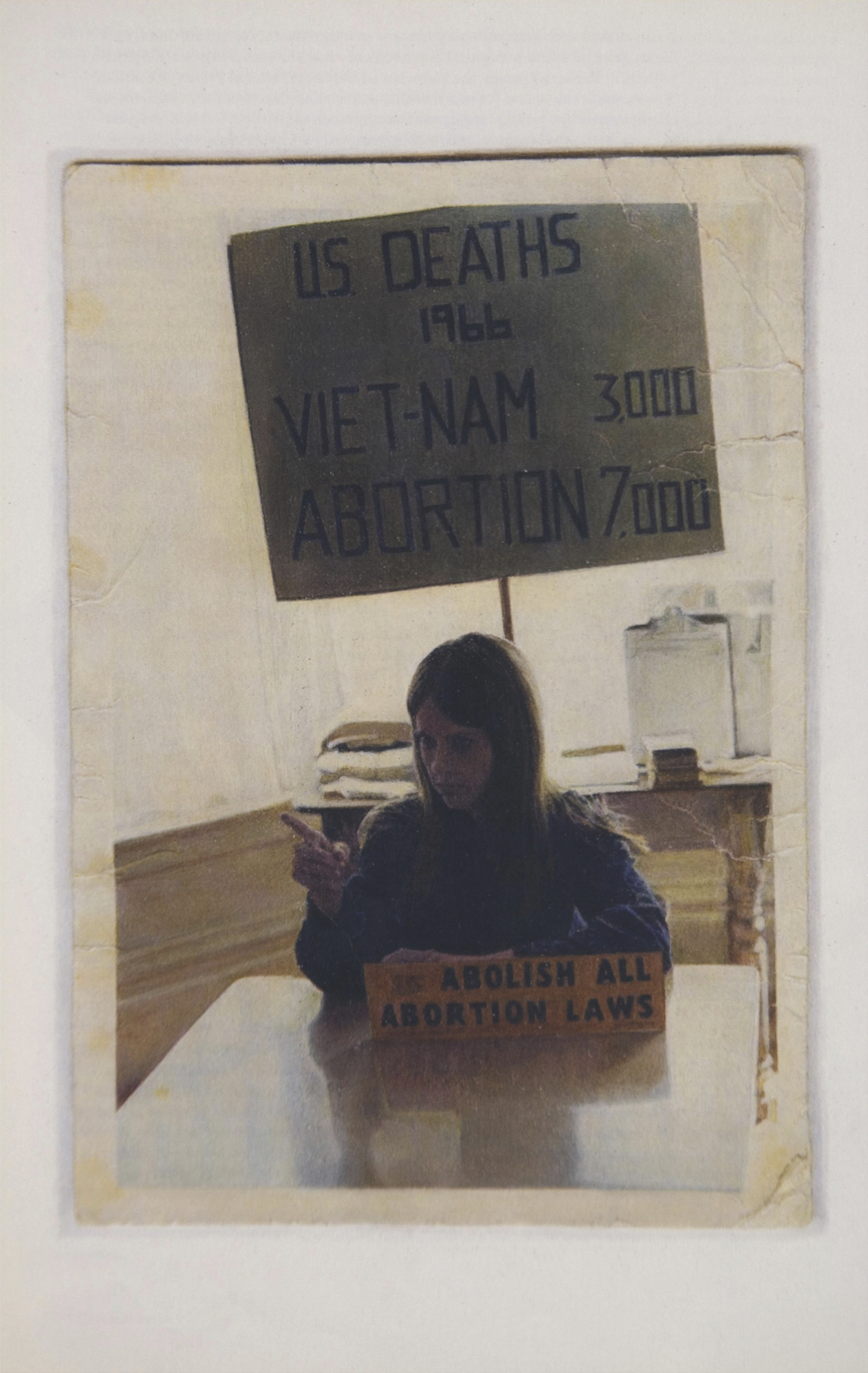

Young Abortion Rights Activist, San Francisco Bay Area, 1966 (Photo Lent from the Archives of Patricia Maginnis), 2005, colored pencil on paper, 127 x 97.15 cm.

On June 24 the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, eliminating federal abortion protections that have lasted for nearly half a century. In a meme circulated by David Zwirner gallery in the days following the news, Barbara Kruger challenged: IF THE END OF ROE IS A SHOCK THEN YOU HAVEN’T BEEN PAYING ATTENTION. It seems, in 2022, we are faced with recognizing, beyond any doubt, the subtle and pervasive effort aimed at undermining the achievements of the Women’s Liberation Movement since the 1970s. Now more pertinent than ever is the task of maintaining this legacy of progress, civil disobedience, and, ultimately, hope that feminist artists and activists, often one and the same, have worked so tirelessly to create.

Originally published in Afterall (Autumn/Winter 2006) and republished here with permission from the author, Jill Dawsey’s essay “Andrea Bowers’s History Lessons” illustrates the pressing relevance of feminist artist Andrea Bowers’s iconography built upon lineages of protest, political struggle, and narrative-making for reproductive rights. Through the visceral, material act of drawing, Bowers commands an immediacy in how we must activate history to frame and mobilize our present. (“Andrea Bowers,” the Los Angeles-based artist’s first ever museum retrospective surveying over two decades of work, is currently on view at the Hammer Museum.)

* * *

For every image of the past that is not recognised by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.

– Walter Benjamin1

I.

Consider this photorealistic drawing. Seated at a table, a young woman fixes her eyes on something, or someone, beyond the photograph’s frame. She raises a finger in admonishment, perhaps, or instruction. Look here, she seems to say. Before her, caught in the shadow she casts on the table, a sign reads “Abolish All Abortion Laws”; behind her another sign, the kind used in demonstrations, relays a sobering tally: “US Deaths 1966; Viet-Nam 3,000; Abortion 7,000.” Death tolls in Vietnam would soon surpass those related to illegal abortions, but both figures would grow exponentially for seven more years until U.S. troops began withdrawing and Roe v. Wade was passed. The young woman–she is Andrea Bowers’s “Young Abortion Rights Activist, San Francisco Bay Area, 1966″ (Photo Lent from the Archives of Patricia Maginnis)–cannot know this in 1966. But her face is turned toward the future. She fixes her eyes on something, or someone–maybe us.

The drawing is a warning from the past sent to the present.

A pointing index finger points to–indexes–a referent in the world by means of its physical relationship to the person gesturing. Similarly, a photograph indexes a past–light patterns reflected onto surfaces at a particular moment in time. With its modeling and technical precision, this drawing mimics the look of a photograph. But as its title states, it also depicts an actual photograph, an object that inhabits space and bears the traces of time. Bowers has carefully copied its yellow spots and dog-eared corners. Unlike some artists working in a photorealist vein, she is not concerned with reproducing a slick surface, a simulated depth of field unnatural to the human eye. For what is most important is that this photograph, this drawing of a photograph, be seen as a historical document, an object that testifies. This is how it was. Bowers does employ a classic trompe-l’oeil trick: the photograph appears to rest on a large expanse of white paper, a faint shadow marking its edges. It looks like we could reach out and pick it up. A 3X5 snapshot rendered life-size, one must lean in close to see that it is a drawing and not really a photograph.

The drawing is a lure that pulls you in. Look here, she says.

II.

Consider this photomechanical reproduction of a photomontage, Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (your body is a battleground) (1989). In some ways it seems more like a relic than Bowers’s archival image. The work was used as a poster for the massive pro-choice march that took place in Washington DC in April 1989. An expert ventriloquist, Kruger engaged the militaristic rhetoric of the opposing camp (think Operation Rescue), deploying mass-media images and texts against themselves so as to advance her own message (avant Adbusters). I invoke Kruger’s precedent here not only because her subject matter is related to Bowers’s, but also because each artist’s work depicts an agitational poster or serves as protest signage itself. Both works grapple with finding a mode of address adequate to the aims of a politically partisan art practice. (Some still call it propaganda.)

Seventeen years after Kruger’s Battleground piece, Bowers responds to new but frighteningly familiar challenges to reproductive rights. Given South Dakota’s recent passage of a bill banning abortion, and with at least twelve other states considering similar bills, Bowers’s recent body of pro-choice themed work (which extends far beyond Young Abortion ‘Rights Activist) is nothing if not timely.

With Kruger’s example in mind, a question arises: why is Bowers at such pains to draw, to copy meticulously Young Abortion’ Rights Activist when she might have reproduced its source image photomechanically? After all, Bowers also works extensively with video, photography and found ephemera, among other media. Her draftsmanship is exquisite, but she’s not married to the medium–she quit drawing altogether for five years in the early 1990s. Throughout the twentieth century, realism and technical virtuosity were often anathema to modern art, connoting conservatism or worse, as the history of Social Realism attests. Politically progressive art has mostly favoured the fragment, the montage, the ‘de-skilling’ of the artist to establish distance from the slick spectacle of consumer capitalism and the instrumentality of totalitarian imagery.

While Bowers counts Kruger as an important early influence, she could not abide the detached perspective, the “exterior position” that much appropriation art seemed to imply to her as an artist coming of age in the 198os.2 She needed to put herself into the work, and the medium of drawing is one that registers the artist’s personal act of making, as well as her labour. For it is Bowers’s labour, and the temporality implied by it, that reanimates and revalues a politics that might be considered outmoded by some. Drawing registers the traces of its own temporal development–pencil moving across paper–as well as the artist’s conceptual process, what Pamela Lee has called ‘the double time’ of drawing.3 As such, drawing serves as a means for translating historical knowledge into material form in the present.

In 1989, Kruger spoke to a moment of profound anti-feminist backlash.4 2006 is also a moment of backlash, but a sneakier, more insidious kind. There is less to lash out against when the prototypical working girl is defined by her Manolo Blahniks, when young women don’t show up at the polls and don’t dare to utter the ‘f-word’. If feminism continues to occupy a fairly unfashionable status in the art world today, generally met with polite indifference or a yawn, Bowers’s work risks a certain embarrassment by unearthing seemingly obsolete objects–old photographs, archival letters, political slogan buttons. But sometimes the things we find outdated, even embarrassing, have the most to tell us about what our current culture has had to renounce in order to shore up its collective ego.

Andrea Bowers, Letters to an Army of Three, 2005, video (stills), 55 min.

III.

As an artist concerned with the historical past, Bowers might be seen as contributing to what Hal Foster has called “an archival impulse” in contemporary art–a tendency for artists to investigate and incorporate into their work various forms of found historical objects and bodies of information.5 Archival materials are indeed central to Bowers’s working process and she typically exhibits scrapbooks of research and ephemera along with her more discrete artworks. Yet Bowers’s project is never a case in mere ‘historical sampling’, as it is with many less-critical practitioners who borrow from past moments and movements with apparent abandon. Over the past several years, her work has developed an extended meditation on the history of feminism, often in connection to the history of non-violent civil disobedience. A crucial aspect of her practice is that it serves not only to preserve or represent history, but is an active participant in the reception and interpretation of history. That is to say that in many ways Bowers herself is doing the work of a historian.

The classically trained dancers cannot help but bring a grace and athleticism to these tactical but otherwise unspectacular physical configurations. Their performances distinctly recall those of the Judson Dance Theater, and especially of Yvonne Rainer, who created a radical dance based on ordinary, task-like movements, all the while emphasising the stubborn physicality of the body. That the video is staged in a Methodist church recreation hall makes Bowers’s invocation of the Judson Church explicit. But rather than simply referencing or paying homage, Nonviolent Civil Disobedience Training posits a historical rethinking of the Judson Dance Theater’s practice, suggesting that its choreography registered, perhaps explicitly drew upon, a vocabulary derived from early non-violent civildisobedience as advocated by Martin Luther King Jr. and deployed extensively in the civil-rights campaigns of the 1960s. One of the most democratic aspects of the Judson Dance Theater was the idea that dance was something that could be taught; foregoing rehearsal altogether, Rainer sometimes taught routines to dancers on stage. In a similar spirit, if we as viewers have paid attention for the ten minutes of Bowers’s video, we too will have found that non-violent civil disobedience can be taught, and that, having just received our first round of instruction, we are prepared to go out and protest.

IV.

Bowers’s archival work demonstrates the relevance of the historical past to the present, passing on useful information and knowledge. But while the current attack on abortion rights in South Dakota and the resurgence of protest culture in relationship to global economic institutions (beginning in Seattle in 1999) lends the aforementioned pieces a self-evident currency, this cannot be so safely claimed with respect to her broader explorations of radical feminism. These include drawings based on photographs of non-violent direct actions carried out by obscure feminist coalitions in the early 1980s against the use of nuclear power. For most viewers, the subject matter will be unfamiliar; even the most avid feminist scholars are likely to encounter something new.

One image depicts several women sitting beneath strings that radiate from one corner like a spiderweb woven across the picture (Magical Politics: Women’s Pentagon Action, 1981, Detail of Woven Web Around Pentagon, 2003). The title works like a newspaper caption to clue us into the scenario: The Weavers Alliance–a group of women unified by their common skills in industrial weaving–wove a web around the Pentagon to prevent entrance. In another piece we view a group of women through a chain-link fence. Linking arms, they form a blockade that will prevent entrance to a nuclear power plant (Diablo blockade, Diablo Nuclear Power Plant, Abalone Alliance, 1981, 2003).

The first thing that may strike us about such images is that these are not the heady days of 1968, nor the peak of the feminist movement, around 1970. 1981 is the wrong moment for nostalgia. Further, these coalitions were formed by women from diverse religious backgrounds, from left-wing Catholics to feminist pagans, united through their shared interests in feminism, spiritualism and environmentalism–a movement that historian Barbara Epstein has called ‘Magical Politics’. Many contemporary feminists (myself included) shy away from what we perceive to be a turn toward new-age spirituality on the part of many second-wave feminists. (‘What makes rage become new age?’ asks Chris Krauss. “By all logic, these women now should be our leaders.”6) Bowers has described her own initial skepticism upon visiting a dance workshop led by the legendary Anna Halpern and witnessing its ‘spiritual’ inclinations. Yet she concludes:

Disregarding anything associated with unconventional spirituality is too easily a ploy to erase value [sic] actions from history. It is my attempt through this body of work, despite my atheism, to remember a group of peoples’ playfulness, their concept of politics as theatre, their egalitarian process and their utopian vision.7

V.

Lately Bowers has been making wall-bound sculptural pieces, intricate flower arrangements somewhere between honorary garlands and home decorations. One, for instance, is composed of delicate white blossoms and winding vines, topped by a calla lily worthy of Georgia O’Keeffe (Political Slogans and Flower Magick: No Hanger, 2oo6). A political button displaying the familiar pro-choice icon of a coat hanger with a red slash through it is nestled below the lily, like an heirloom brooch worn at the neck of a lacy blouse. Edged in red, the lily bears a strong graphic relationship to the button with its red slash. This makes it difficult to avoid the persistent association between flowers and female genitalia–certainly O’Keeffe could never escape it. Intentional or not, Bowers’s flower arrangements suggest that your reproductive organs have something they would like to say. One floral piece wears a green button that reads, “Fuck Authority!”

Andrea Bowers, Political Slogans and Flower Magick: Don’t Fuck with the Ladies, 2006, paper, wire, gouache, and a found political button, 137.16 x 40.64 x 11.43 cm.

Bowers has also recently combined vintage pro-choice buttons with pieces of wrapping paper that bear modernist design patterns, such that the design of the button coincides graphically with a detail of the paper. The pro-choice message thus comes to us wrapped as a gift. While the button is nearly lost within a pattern of stripes or organic forms, their slogans enact their own civil disobedience against the wrapping paper, blaring out: “Pro-child Pro-Choice,” or “Keep Your Laws Off My Body.” The high-end wrapping paper is smartly designed to riff on past modernist patterns, updating them with cool colour palettes (perfect for yuppie wedding presents and such). Here late-modernist design encounters its own worst fears: decoration and kitsch (a distinctly ‘feminine’ political kitsch). Bowers does not stop here. She makes photoreal drawings of her wrapping paper/button collages, or alternately pastes the wrapping paper to a wall in grid formation, interspersed with Xeroxed archival letters from the 1960s, requests sent to a group of abortion activists for information about doctors in Mexico and Japan who could offer safe abortions. When the wrapping paper goes on the wall it becomes wallpaper, and these lost narratives of desperation and despair emerge from the patterns, as in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s famous short story “The Yellow Wallpaper.”8

The group of activists to whom the letters are addressed were known as the “Army of Three,” and they form the core of Bowers’s matrix of works on abortion rights. From 1964 until 1973, when Roe v. Wade was finally passed, these three San Francisco Bay Area women–Pat Maginnis, Lana Phelan and Rowena Gurner–campaigned tirelessly for the repeal of abortion laws, founding the Association for the Repeal Abortion Laws (which would became NARAL), distributing leaflets, publishing information in alternative newspapers and leading workshops to educate women about safe abortion techniques. Girls, mothers, boyfriends, fathers wrote to them over the years, imploring them to provide the invaluable list of foreign doctors that the group had compiled. In Bowers’s video Letters to An Army of Three (2oo5) actors of varying ages and races read the letters aloud, breaking the silence on what for so long could not be spoken. Flowers appear again in this video, carefully arranged in bouquets resembling those in Dutch still-life paintings. The flowers fade in a slow dissolve as each actor appears, and for a moment there is a visual confusion, a merging of figure and flowers. Here the tension between figure and ground that appears in so much of Bowers’s work is paralleled by a tension between speech and silence. Just as the disruption of a figure’s spatial boundaries implies a dissolution of that figure, and accordingly the loss of identity, the inability to speak renders the subject not only mute but virtually nonexistent. Against the political forces that would willfully erase this written but silent history, Bowers insists on a clamour of voices.

EPILOGUE

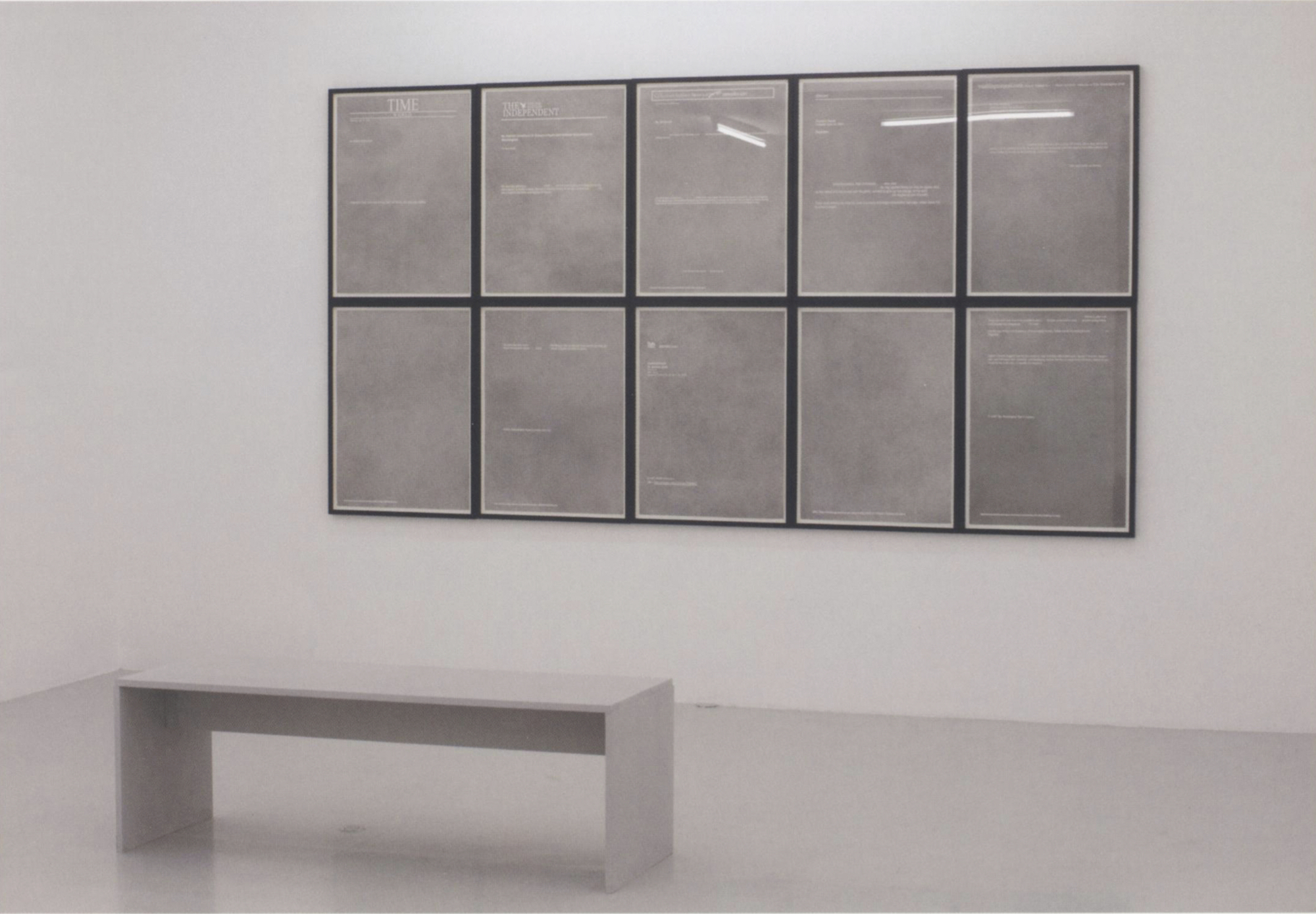

Andrea Bowers, Eulogies to One and Another, 2006, installation view.

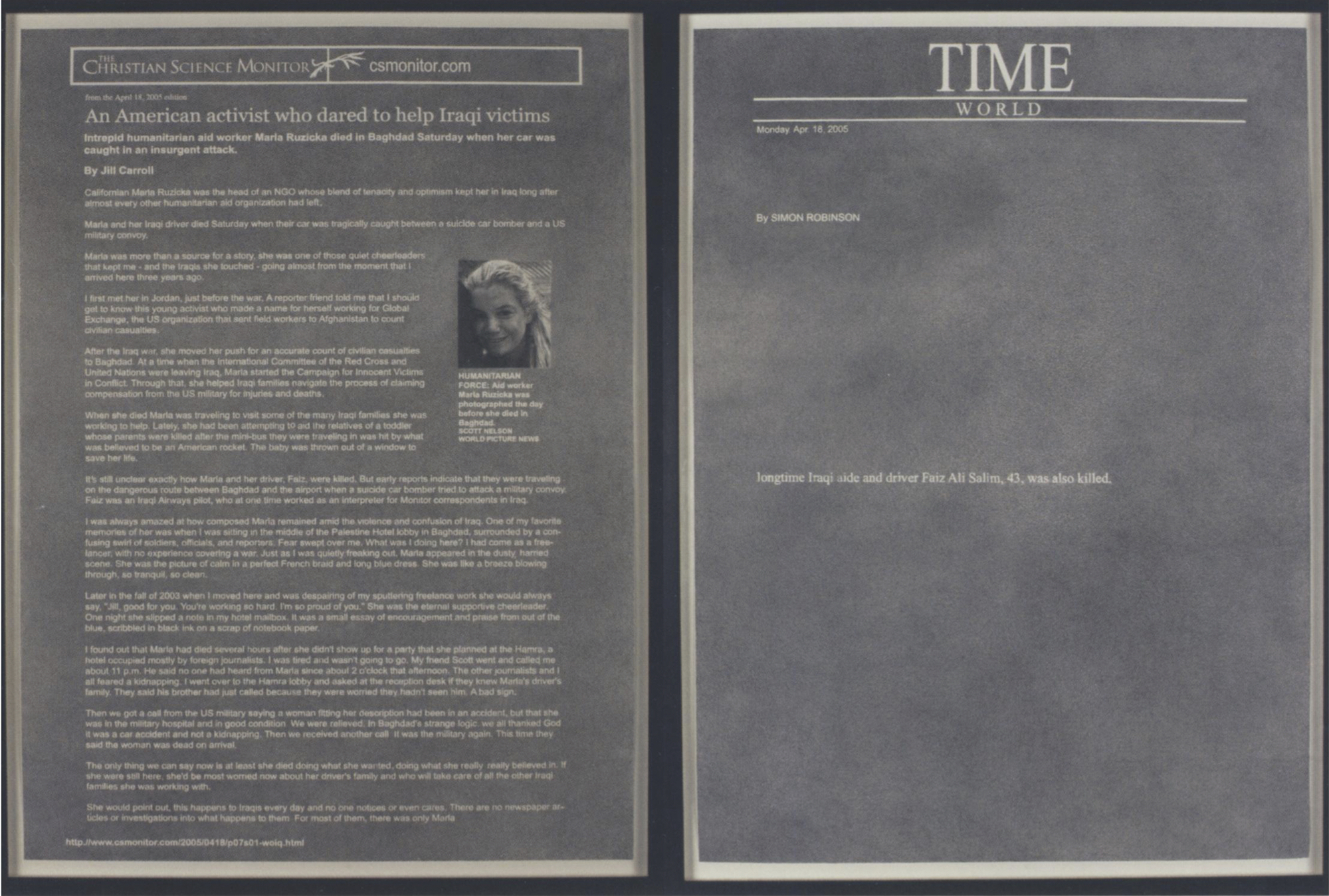

Bowers’s most recent project, Eulogies to One and Another (20o6), comprises a series of drawings based on obituaries that appeared on the Internet in the days following the death of 28-year-old American activist and aid worker Marla Ruzicka in a car-bomb attack in Baghdad in April 2005. For a couple of years Ruzicka had been going door to door in Iraq with her work partner and translator Faiz Ali Salim in an attempt to keep an accurate running count of the number of civilian deaths. Salim was also killed in the attack, but he is mentioned only in passing in most of the obituaries, often referred to as her driver.

A much-mourned victim of the war, Ruzicka was eulogised by the likes of Senator Barbara Boxer (who, in an address before the President, described her as “a humanitarian angel”) and by many prominent journalists.9

Bowers has painstakingly drawn replicas of the eulogies in their Internet format, but the ground of the page (or screen?) is shaded densely in graphite, with words composed of the negative space of the white paper support. She presents the series of ten eulogies as a grid, twice. Each individual black frame contains the text of a single eulogy. It is easy to get pulled into Marla’s tragic narrative as we read that she would encourage military officers and US officials to hug each other, to remind each other that they were all still human in the midst of the war.

Upon viewing the second set of eulogies, however, one experiences a sudden shift in gestalt. For in this second set, a repetition of the first ten, Bowers has omitted all words except for those that reference Ruzicka’s partner in CIVIC, Faiz Ali Salim. The drawings are now shockingly sparse. The eulogies are gone. Fragmented sentences read like perverse concrete poems: “Faiz among those killed.” Or, “driver leaves behind wife and two-month-old daughter.” Some pages are simply fields of grey static, except for the URL at the bottom of the page.

Need it be said? Iraqi deaths are so often buried in the American media’s negative spaces.10 Lives are not equally valued. In Eulogies to One and Another the act of drawing becomes an act of memorialising. Like the most effective memorials (Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial comes to mind), this one acknowledges loss through a negativity, a palpable absence. Here Bowers makes the case that it is not only the historical record that must be preserved and acknowledged. We must also look hard at the information that surrounds us, the archives amassing in our midst.

In many ways, Eulogies to One and Another may be Bowers’s most nuanced feminist work yet. In her 1982 essay “Notes on Quotes,” Martha Rosler warns against using women as “a token for all markers of difference,” observing that “appreciation of the work of women whose subject is oppression exhausts consideration of all other oppressions.”11 There are always others in thebackground.

Andrea Bowers, Eulogies to One and Another (Christian Science Monitor and MSNBC.com, 1 of 4) and (Time World, 3 of 4), 2006, graphite on paper, each 76 x 55.5 cm.