Artists at Work: Candice Lin

by Silvi Naçi

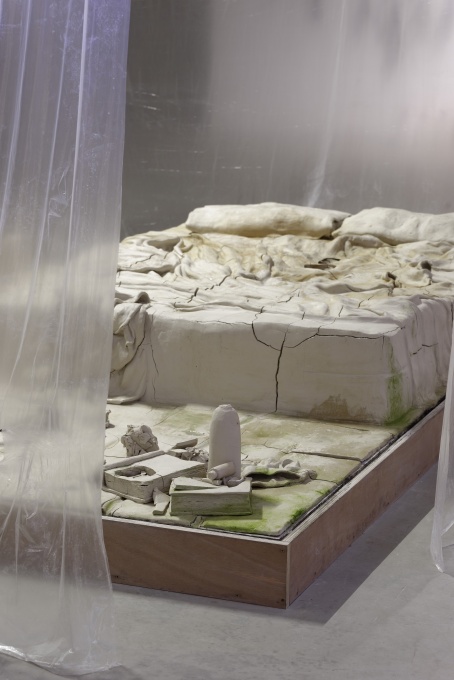

Candice Lin, Future Sarcophagus. Ceramic, soil, worms, maize, rice, wheat, sugarcane, opium poppy, potato, ginger, pepper; 50.75 x 72 x 35.75 inches. Installation view from Pitzer College Art Galleries, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Candice Lin is an interdisciplinary artist whose research-based practice lends itself to sculpture, drawing, video, ceramics, and installation. She is co-founder of Monte Vista Projects, an artist-run collective and space in Los Angeles, and an assistant professor in the Department of Art at the UCLA School of Arts and Architecture. In her work she offers a number of windows through which to encounter the colonial histories embedded deeply within her often living and organic materials. A multi-sensorial endeavor that allows for animate and inanimate bodies to co-exist, living beside and within one another, Lin’s work further expands the idea of panpsychism. In the following interview, we discuss her past and current projects as well as her upcoming exhibitions.

Silvi Naçi: Ever since I heard you speak at the Hammer in early 2019, I’ve been thinking a lot about redistribution of power in the material world, and reimagined futures, intertwined with the effects of decolonization and the internal colonizer that’s left behind, which Frantz Fanon speaks so beautifully to. What futures do you imagine had we done things right and respected the earth and indigenous life? Can you talk about these reimagined worlds and the interactions happening through the cultures and colonial histories of your materials?

Candice Lin: I don’t know if I’m optimistic enough to imagine a space uncontaminated by colonization. I feel like the fabric of my being and existence is so interwoven with the violences of colonialism and imperialism that it’s not just that I’m making work from a position of internalized colonization, but that there is no way I could ever stand outside of or have an exterior separate from colonization. My interest in indigo began from a tactile response to its color, both in the dye pot and in the fabric. And this interest deepened as I learned about how this material, this plant, traveled across so many different global trade routes.

I was interested in how many cultures had their own regional and specific imagery using indigo that transformed through colonization and cross-cultural influences of the global trade. For example, 19th century Nigerian Adire prints meld British colonial imagery of the crown, the king and queen, and the Union Jack with traditional geometric motifs representing philosophical ideas or local flora and fauna. Even the methods of how the designs were applied changed — from being drawn from cassava paste with a chicken feather to being stamped through a stencil that used a flattened metal tea tin (an off-product of global trade during British colonization between all of its colonies). This changed the crispness and gestural qualities of the line drawing designs. The same kinds of hybridization of techniques and imagery can be seen in Japanese katazome (rice paste resist-dyed indigo) textiles as well, which reflect cross-cultural influences from China, Portugal, and other countries despite stringent restrictions on foreign access from the 17th-19th centuries.

Candice Lin, Map to an Unknown Sea. Indigo, sugarcane fibers, opium poppy stems, yucca, cotton rag pulp; 58.5 x 42.75 x 2 inches. Installation view from Pigs and Poison, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

SN: I see a lot of artists being talked about from the perspective of policing identities and ownership of mediums — “call-out culture.” There seems to be this pressure to only work with specific mediums or materials. I feel like possibilities become exponential when there is space to explore and investigate from an intersectional and cross-cultural point of entry — for example, the use of cochineal and indigo in your work in relation to what has happened through centuries of colonization and diaspora.

CL: Are you asking if I get called out for co-opting specific mediums or histories in my work?

SN: Yes, and how the work goes beyond you. The histories which come together in the work ask the viewer for a deeper understanding and investigation.

CL: I feel like that kind of question is so specific to these political times. There seems to be a rise of a kind of reductive essentialism where what one is allowed to speak about, or make work about, or research about, has to align very literally with one’s perceived identity. To me this feels troubling because it undoes all the work that has been done to see how histories and identities intersect and are entangled. I had some work, some older drawings that were these watercolors that reimagined John White and Jacques Le Moyne’s watercolors of the “New World” – the Americas at the moment of first contact with Europeans – and they were going to be included in the Pigs and Poison exhibition at the Govett- Brewster Art Gallery in New Zealand. The curators were concerned because they got feedback from their Maori curator friends who felt that, as a non-indigenous person, I didn’t have the right to make or show work that’s about the colonization of any land, even if it’s of the Americas. The curators weren’t giving me an imperative to take the works out of the show but they wanted to be sensitive to the local perception, especially as they were not from New Zealand (one is Canadian and one is Swedish) and nor was I. They had a lot of anxiety that negative feelings about my questionable “right” to make work about this subject would detract from the larger meaning and reception of the whole exhibition, so we took the works out.

While I understood why the Maori community and other indigenous communities might have valid reasons for questioning my interest in this subject and my use of this subject for my work, I also felt disheartened because it forecloses the possibilities of thinking through connections across time, and how these legacies of colonization unfold in complex and layered ways that affect many different people in different ways. In this case in particular I was puzzled about the implied ownership one has over a subject matter because it bases that ownership in essentialist ideas of identity – it prioritizes an abstract idea of transnational indigeneity over my place-based experience and grappling with what it means to be an American, a child of immigrants growing up imbibing American ideologies and trying to understand what it means to be part of a nation shaped by violence and colonization, much of it ongoing. I should say that much of the imagery in those watercolors also pictures figures that appear Asian or Black or indigenous. I wanted to talk about all the different legacies of violence – African slavery and Asian indentured labor, as well as colonization and indigenous genocide, disposession and enslavement.

By the same logic that those works were pulled from the New Zealand show, one could also have made a similar argument to exclude a new series of paintings that were included. These have images of dead pigs, dressed in human clothing, decomposing in the desert. They’re from the Undocumented Migration Project, a long-term anthropological study by UCLA Professor Jason De Leon and his team of researchers, who wanted to use the pigs as surrogates for human bodies that are lost in the Sonoran Desert in order to re-estimate and better track the bodies of migrants who die crossing the border but aren’t counted because their bodies are never found.

These works operate within the exhibition to connect the historical context of 19th century Chinese immigration – specifically, the way that Chinese coolies and the exclusion laws that were passed to restrict Chinese immigrants and deny them citizenship (despite in some cases having lived multiple generations within the U.S.) have shaped our immigration policies to this day and the contemporary situation at the border. Somebody could very easily say, within a similar logic: “You don’t have the right to make work about the U.S./Mexico border crisis because you are not Latinx.” But I would have to say I don’t agree with that. I believe that there is something to be gained by looking at the longer span of history and the cross-racial ways different groups are entangled and targeted historically, and the way privilege and exclusion within a nationalist project shifts upon different groups at different times depending on various factors. I also made that work specifically thinking about Chinese-American families I grew up with, many of them with conservative politics who support Trump and his racist immigration policies. I wondered if these family friends would ever question their proximity to whiteness and their lack of racial solidarity if they could learn the longer view of history where they were once conscripted as the “illegal alien.”

Candice Lin, Measuring Pigs in the Desert, 2020. Oil, encaustic, and lard on birch panel. Courtesy of the artist.

SN: There’s also a huge hole in the education system. In the States folks are taught a version of American history that privileges the white narrative instead of a wider conversation about all peoples whose histories have been erased from the curriculum. That becomes dangerous when paired with a passive attitude in regards to looking at art. Being Albanian and based in Los Angeles means people have a hard time with my personhood and my work because its context isn’t “widely” known or Americentric. I don’t think I can offer everything in my work, but at the same time I’m willing to meet the viewer halfway. It’s difficult if they’re not willing to do the research.

CL: Yeah, I think it’s interesting. Especially in school settings where certain demands that the student consider “context” are actually about accommodating whiteness, where the assumption that your work should be accessible to a supposedly universal, flattened American context is actually a very small subsect of America that decides what is legible and what is not. Also sometimes the question of “who is your preferred audience?” is never asked.

That said, I do think thinking about context and audience is important when making work. The New Zealand show I mentioned was originally supposed to open in Guangzhou first, at the Times Museum (in March 2020, but that is now postponed until next year) and later to travel to New Zealand and Bristol, UK (at Spike Island). The order of how it was shown got scrambled, but actually my ideas for the show began with the first invitation, to make a solo exhibition in Southern China in Guangzhou, formerly Canton. So the 19th century Chinese history as tied to British colonial history and American imperialism around that area of China were things that came out of specifically thinking about a Chinese audience in Guangzhou, and thinking about my diasporic position specifically as a Chinese American artist who has lost, in many ways, information about Chinese language, history, and culture.

SN: It seems like there’s this dance living and existing in a double consciousness, something that W.E.B Du Bois speaks to, and further, an expansion of it that draws itself out laterally, like rhizomes.

CL: Yeah, yeah, and the internalized colonization you mentioned earlier relates to that conservatism that many of the Asian American families I grew up with have. I was so depressed to learn from my mom (and she was too – I’m glad she doesn’t share many of her friends’ political opinions) that most of these families I grew up with voted for Trump and his racist policies because they saw themselves as exceptional to who he was targeting. They saw themselves as proximate to whiteness and included in the majority. I was interested in speaking to a Chinese audience in China that might also not question being part of the dominant group in power, to have them reconsider their own forgotten histories of having been minoritized, and what that might open up in terms of thinking of future ways forward for cross-racial solidarity and international entanglements.

SN: As I look at your work, ritualistic practices come to mind, almost like forming sacred spaces for beings of all kinds. If somebody were to uncover these text-fabric works years from now – I wonder what they could make out of it. Can you talk about ritual and the ways in which the materials carry this interconnectedness?

CL: I think the aspect of my work that people sometimes identify as ritualistic is the way that I make an elaborate inner logic to the work, such as the inscriptions of unreadable text on these indigo textiles that feel like incantations, or spells, or the circulation of liquids within elaborate systems of distillation, boiling, and pumping. I realized that since I was an undergraduate student making art, I’ve always had this penchant for writing things and then writing over them to make them unreadable, charging them by writing over them with other shapes, making their normal functionality as words obsolete, and keeping their meaning hidden but palpable in a different way. Using systems of distillation that might ordinarily be used in science for very specific purposes of isolating and concentrating a material to add to its capital, but using these processes instead in a non-functional way to make, for example, a colonial stain, is also like a ritual because its reason for being used is not geared towards production but towards affect. It creates a kind of ritualistic intention through the physicalization and repeated circulation of liquids.

I’ve lately been doing this thing where I’ll be listening to the news as I’m drawing or writing it. I’ll just write down words that I’m hearing and as I’m listening, and then I’ll go back and cut them apart with other letters and shapes. It’s kind of a personal ritual of digesting streams and streams of dismal bad news and transforming it into sigils or spells for the future. It makes it about this specific time period while also opening it to all future intersections of time and beings who will, hopefully, experience the work later.

Also some of my work is directly connected to ritual in that I create altars, like I did for the installation La Charada China, where the presence of altars are serving a memorializing purpose, to honor a forgotten or marginalized history that is pretty grim, as in the case of the 19th century Chinese coolie laborers. In that history many workers who were interviewed recorded that their coworkers’ bodies were never buried but were desecrated on purpose or burned to make bone charcoal that was used to refine sugar, so I wanted to make a space where people could learn about this little known history, a space that was also like a memorial or a grave where there was often none.

SN: With your installation works, especially those that travel to and from different places, there’s an element of holding space and time that operates in relationship to the history of the site where the work is being installed. It’s almost as if viewers are entering a sacred energy sphere that’s changing constantly. I’m thinking of your sarcophagus work shown at Pitzer Art Galleries (Natural History: A Half-Eaten Portrait, an Unrecognizable Landscape, a Still, Still Life). Can you talk about this idea of holding space and how it shows up in your other works?

CL: Well, that work in particular is made to literally hold my future dead body, and it has this funeral reference that maybe feels very solemn, although I’m not sure it’s sacred or holding space for the sacred… Can you say more about what you mean?

SN: I’m specifically thinking about how the works at times aren’t fired and morph and change while the exhibition travels – they aren’t stagnant and continue to grow with each presentation.

CL: Ah, I think I know what you’re saying. Somebody once asked me, “What do you do when you’re installing and it fails?” And I was puzzled and said, well, it kind of can’t fail because I don’t have any set outcome in mind. It’s more like I’m setting up a scenario or a proposition of materials that are going to enact transformation on each other, go through different processes, and I’m open to whatever the results are. I have an idea of what might happen, but it isn’t actually in my control. So I guess yeah, that is a way of holding space for the materials to enact their effect on each other.

SN: Yeah, it’s just so exciting to see that. I loved James Baldwin’s novel Giovanni’s Room and the work you created, A Hard White Body, that had his story as part of the conceptual framework. It was incredible – like, here’s the two people and whatever is going to happen in here is the work.

CL: And in that installation, it was also: here’s the room for all of you that enter the space… Here is the urinal as an invitation for you to piss and have your bodily liquids recycled to care for this bedroom with its porcelain rumpled sheets, where you can imagine your body lying on this moist bed together with mine, and where our piss mingles.

Installation view from Candice Lin’s A Hard White Body, Bétonsalon, Paris, 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

SN: What does the germination process look like when you begin a work? How do the ideas form in your mind? What do you know first? Do you think of a proposition first or does an element come to mind and then you build from there?

CL: It all depends. In the case of A Hard White Body, I knew that I wanted to make work about porcelain when I fell in love with the material – high fire porcelain – in 2010. Porcelain was my introduction to working with clay (for the piece The Moon) and I instantly loved the way it felt in my hands. Several years later, I had read some histories of porcelain and the way it was traded in Europe and how Europeans made all these alternate clay bodies (some with bones ground up in them) in their attempts and failures to replicate the kind of porcelain that came from Asia. And then I got the invitation to do a show at Bétonsalon in Paris in 2017, and to be in residency for three months before that to research and build works, which was such a gift. So I started researching specific people that were tied to the site-specific location of Paris in particular, and France in general.

I was thinking about James Baldwin and his time in Paris in the late 40s and early 50s and how he made it his home and lived the last 17 years of his life in St. Paul de Vence, in Southern France. I was rereading Giovanni’s Room at the same time that I was reading a book by Glynis Ridley, a biography on Jeanne Baret, a French peasant woman in the 18th century. I was just really struck by how in both descriptions there is a space described that is claustrophobic and stifling yet also a space of freedom and wildness. In Giovanni’s Room, the bedroom between two lovers was described in this really visceral way where it almost becomes this other character, the character of the witness. Then with Jeanne Baret, there’s a lot of descriptions of the ship cabin that she crossed the globe in as a participant in the 1766-69 Bougainville colonial expedition. Jeanne Baret is thought to be the first woman to circumnavigate the globe and she did so crossdressing as the male valet to Commerson, the person who was really her lover and was recognized as the official botanist of the expedition even though he was reliant on her for herbal knowledge and manual labor in gathering and studying plants. Various ship journals that the biographer Ridley goes through describe the ship cabin with its low 5′ ceiling and the smells of vinegar from preserved specimens and medicinal smells mingled with body odors – Baret took care of her lovers’ leg that was rotting with gangrene. The way that small cramped space was described in the book also made me think of Giovanni’s Room, so then I knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to make this bedroom out of porcelain that is never fired but kept wet by a liquid – something precarious that might crack and fall apart at any moment, as porcelain has a tendency to do, something requiring constant care. At first I thought the liquid would just be like a tisane, an herbal tea for calming the skin, based on Baret’s herbal archives. But then the piss got in there because I was thinking about urinals and porcelain, ideas of purity and filth, and how they play into cultural erotics.

SN: Can you talk about these moments of translation as spaces of possibility?

CL: It’s interesting you ask about translation. As we were translating stuff for the French part of the pamphlet that accompanied the exhibition, there was a lot of text I had written. For example in the video script I wrote, “the beloved” that the narrator addresses is purposefully gender ambiguous. And so to preserve this ambiguity, they went through a number of things within the queer community and came up with a solution of “il,elle,” which references the fairly new term “iel” which, as I understood, is kind of like how we use “they” to designate a more non-binary gender. In the case of the video script, I wasn’t interested in using a non-binary term but something that preserved the purposeful gender ambiguity that could be either masculine or feminine. So, it was kind of a hybrid. I was lucky that I was working with such good translators and curators who knew to ask those questions based on a deep understanding of the work and what my intentions were.

SN: Oh, I actually meant the translation of the work to a specific place, or the way it changes after you begin to install.

CL: Oh, sorry, I am too literal sometimes! I thought you were asking about translating texts from English to French. Yes, the work starts off as an initial idea that is, in some cases, specifically tied to initial ideas about the location. When I have been able to, I’ve come to those places for a few weeks or a few months and done research on site and sometimes this has changed the research project or the show idea – either because I realize my assumptions weren’t correct as I get deeper into the research materials and learn more, or because I can’t access what I need to carry out the original proposal. An example of that would be in the Dominican Republic. I went there planning to research plants and herbal remedies used on the island as a way of speculating on poisons that may have been used during the Haitian Revolution. I also wanted to learn more about tobacco production and interview workers in the factory that funded the residency I was on. But because I couldn’t speak Spanish and for some other reasons I don’t want to get into here, I couldn’t get very far in gathering information through talking to people, so I ended up “researching” plants by dosing myself and taking notes on the experiences which I made into a text piece and a video.

Candice Lin and Patrick Staff, STRESSED HERMS, SWEAT, & PERIOD GAS. Installation view from Institute of Contemporary Arts at NYU Shanghai, 2020. Courtesy of Candice Lin.

SN: Do you ever come into confrontation with galleries or museums that have issues with the living/breathing aspects of your work? And do they ask you to change it?

CL: They always are really excited about the initial idea. But the reality, the maintenance and the risk the work creates is a whole other thing to grapple with. When I made System for a Stain at Gasworks they loved the proposal idea, but were nervous about the floor because the concrete was newly poured. I was joking with the curator about the anxieties around, “Can you make sure the stain doesn’t leave a stain on the floor?”– when this whole show proposal was about making a stain! But we made it work with their talented team, and laid down laminate to protect the concrete floor, although it did leave a slight “zebra striped red stain.” Then for Made in L.A. at the Hammer, they liked the idea of this earthen room that I proposed for La Charada China, but were nervous about the earth being tracked around. And then once flies started emerging from the piles of dirt we brought in, this caused a big risk for other artworks in the museum so they made me fumigate it. I was worried about the fumigation making the seeds sterile – and it might have, as only a few of them sprouted. Working at the Pitzer Galleries was actually very simple despite 300 lbs. of dirt and worms and beetles. The person that took care of it, Chris Michno, wore a respirator when he fed the meat paste to the flesh-eating beetles because it made him have horrible asthma otherwise (also it just smells god-awful), but he was very sweet about it. They never tried to make me stop or change my plan even though it was very high maintenance as the worms and beetles in the sculptures had to be watered and fed daily.

SN: I’m very interested in this idea of “panpsychism” (which Steven Shaviro and Elizabeth A. Povinelli write about) that offers to look beyond human-centered thought and allows for objects to just be. In other words, even though some organic entities do not have brains, they do have consciousness. There are so many living entities in your work, from the dyes to the unfired clay… What do you think of your relationship with the objects, materials, and mediums in your work?

CL: Yeah, I’m drawn to what maybe neo-Materialists might call a vibrancy of matter, where things that may not be alive by human standards still exude a kind of vitality. As I’ve been working with indigo, I’m so aware that it’s alive. The color is created through a fermentation of the plant matter and bacteria and you have to feed it with broth, rice bran, and ash –and if it’s unhappy it will die and the color will get more dull or just not work. (That’s already happened a few times as I learned how to best care for it!) Part of my interest in these kinds of bacterias and molds and plants and insects is wanting to think through the world and all its materials from a de-centered, non-human point of view, and to think about our interspecies entanglements and interdependencies. But I think the second part of the answer to your question would be addressing the captivity of the insects I sometimes use. Sometimes people have asked me how I feel about the politics of that. Obviously, since I use them in my work, I feel fine about the politics of that.

SN: I think it’s fascinating because no matter how well you care for something, folks (in the art world especially) can still find a problem with the work. I know you’re still caring for the insects that were in your show at Pitzer and I wonder if needing to navigate all this so carefully ever gets in the way of making work.

CL: Yeah, sorry – I didn’t mean to be flippant or dismissive. I think it’s a valid concern. But I do think it gets down to a splitting of hairs. My ethics around art-making are that I see my art practice as continuous to my living and being in the world. So I wouldn’t go buy a little kitten and cut its head off for art obviously – sorry, why did I say that! It’s horrible to even think of that image. But for example, when I use the insects, I get them from a source where they’re sold to be reptile food. Or in the case of the flesh-eating beetles that are bought by museum conservators or taxidermists who want to use them to clean off bones, their lives are the same quality if not better under my care as they would be normally. Sure, it’s probably not their best life. They probably could have some fantasy best life where they’re free in the wild, eating corpses under the ground or something, but I think they are happy enough with the quality of life they get with me – at least they keep breeding, much to my dismay! They are in my studio now smelling it up. So yeah, I don’t think it’s immoral for me to participate in the buying and selling of insect life (how could I, as I also participate in the buying, selling, and eating of animal and plant life as an omnivore?) Others might find both of these choices immoral and would not choose to do either, but they are choices I’m comfortable making. That doesn’t mean that these choices are not violent or not problematic – but they are decisions I make as I go about life accepting a certain amount of complicity with and embeddedness within a system of violence.

SN: You can’t get away from this cycle of interspecies interpolation where one is constantly being implicated in another’s life. Anna Tsing writes a lot about the networked world-building of fungi across plants as a mutual and relational collaboration – a sympoiesis. So in that sense I don’t understand why as artists we strive for this idea of purity or separatism.

CL: I think because artists are idealists a lot of times, so there’s a desire for a morally pure or irreproachable space to be in, especially if we are trained in art schools to see critique as an orientation towards the world (then there’s the assumption that the one critiquing better be above and irreproachable from the person/institution/thing it critiques), but I don’t think it’s a reality.

SN: I think it perpetuates a colonial mindset – if something is pure and untouched, then it can be taken over. But that goes against working together, so how can we think of collaboration? In a sense you are collaborating with your materials.

CL: Yeah, I mean, I do think that art-making is just continuous with life. You make choices and you should make them with care, but I don’t think you can ever make them in a way that places you in a blameless space. I think you’re always implicated within the same social structures you live within, even if you have revelatory moments of being able to see that the norm is not acceptable or should be questioned.

Detail of Candice Lin’s Future Sarcophagus at Pitzer College Art Galleries, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

SN: Can you tell me about the wearable tent you’re making now for your upcoming exhibition?

CL: I think it’s going to feel nice to lay underneath it. There are these ceramic cat pillows on top of painted rugs that people can lay on, and I’m sewing these marble fabrics into blankets. You can lay there and there’s this story of White-n-Gray, my old feral cat friend, playing as an audio track in the space. The work will be at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and then it will travel to the Carpenter Center at Harvard. They’re really letting me have a free license with my love of cats. I said to the curators, I hope you guys are going to be able to write about this in a way that doesn’t seem lightweight! The work is about cats because it’s about solace and comfort woven into life in ruins. The indigo patterns I spoke about are visual legacies of global colonialism, but they are also testaments to craft traditions absorbing imagery tied to trade and conquest and turning them into images of beauty, resistance, and syncretism. I’ve been thinking a lot about the subtitle to Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, and about the patches that make that life possible.

SN: Can you say more about ruins? Tsing writes a lot about fungi – that it’s so resilient and grows after disastrous events, like after Hiroshima.

CL: Well, we are living in ruins now. And I guess I’ve been thinking of her book as I’m asking myself the kinds of questions that many others have been asking in despair… How do we live in times like these? What can we change collectively? What things do we not want to return to “normal”? How do we adapt, repair, survive, and thrive in this world of chaos, violence, pollution, and sickness we have created? How can we take this time of greater isolation and slowness to reevaluate and change our values and our inertia?

SN: Are any of the institutions asking you to rethink this piece in case the pandemic continues?

CL: We’ve talked about that a little bit but haven’t really tried to come up with an alternate experience yet. This piece is really made in hope – it’s made in the hope of when we can be back lying down next to each other, or stretching in a space together, or touching our hands on the shared surface of the tactile theater (another sculpture I’m working on) without pre-sanitizing! It would need serious rethinking to make this work exist in a world of anti-touch and spatial distance when the works are all about touch, intimacy, closeness, and being together.

SN: What is the significance of the characters you are using in the ceramics? Can you talk about that imagery?

CL: Well, there are these characters that I keep calling “cat demons.” They’re kind of cats and kind of demons. They developed out of the imagery I was researching when I made my future sarcophagus. I was looking at these lokapala/zhenmuyong and zhenmushou sculpture – Chinese tomb demons – which are these animal/demon/human hybrids that have flaming headdresses, big ears or horns, or rooster combs on their heads and they’re usually stomping on other animals with their feet. They look amazing. I saw some of them last summer when I went back to Fuzhou, my father’s hometown, for the first time in 25 years, in a history museum there. They must have gotten into my imaginary because I’ve been drawing and sculpting these characters that look somewhat like them ever since.

So, the ceramics are loosely based on these tomb guardian sculptures (some of the ceramics are also based on George Psalmanazar’s “idol” of Formosa). One of these cat demon figures is 3D scanned and an artist, Yotam Menda-Levy, is helping me to animate it so that this cat demon teaches you qi gong, which has been really helpful to me during quarantine and the long hours in front of the screen. And it ends with a dance party. It all might change by next summer (2021), but right now I imagine an installation where the outside of the tent structure will be more active with the dance and qi gong video and tactile theaters. The interior will be a calm space of rest and laying down to look at the drawings in the textiles from a reclining position while listening to the audio. The audio is a little bit of a sad story because it imagines White-n-Gray’s last day before he disappeared – he lived on my porch off and on for 11 years and was really camped out there every day for the last 3 years but he never let me tame him. You could only pet him when he was eating and even then he’d sometimes take a swipe at you. He was really special. I think he died naturally.

SN: I love the idea of a voice reading to you about a cat dying while you’re laying down on this custom-made bed that’s also caring for you. It’s such a powerful dialectic between all the elements you have to carry and contend with.

CL: Yeah, that’s true, and in the story the dying is linked to dyeing – as in indigo dyeing – and some of the history of indigo is told through the narrative where White-n-Gray eats the indigo plants in my garden and then vomits it into a pool of fermented liquid that grows to the size of a pond, and then he steps down inside the pool of indigo and he’s in a world called the Blueness. It’s an alternate world where cats (and one raccoon and one opossum) are the main protagonists.

Detail of Candice Lin’s Future Sarcophagus at Pitzer College Art Galleries, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.