Artists at Work: Cauleen Smith

by Travis Diehl

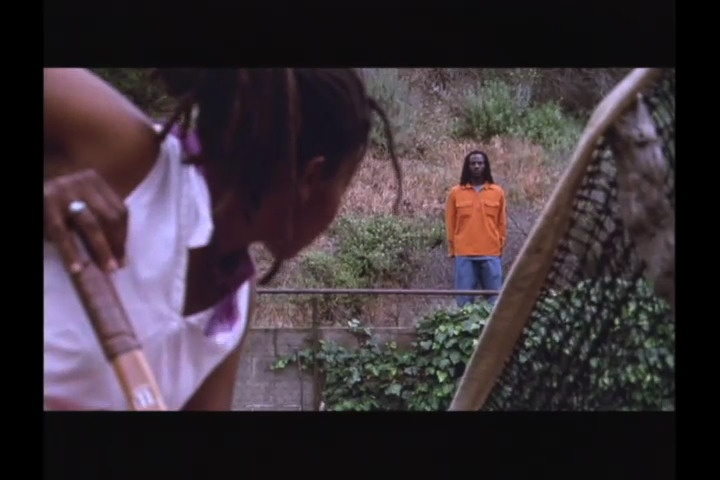

Still from Remote Viewing, 2011, digital film for projection, color/sound. Total running time: 15 minutes, 24 seconds.

Cauleen Smith grew up in Riverside and Sacramento, California, and recently returned to the Southland as faculty in the art school at the California Institute of the Arts. Her experimental films and performances—protests, processions, flash mobs—combine the syntax of popular movies, mainstream politics, and contemporary art into surprising, ambiguous, often personal statements about race, inequality, democracy, and our place on this planet. Smith’s work is legible in a way that exceeds the patterns of the forms she chooses. While a film student at UCLA, to cite an early example, she was briefly expelled for trying to make her MFA thesis feature length. She finished the film anyway: Drylongso (1998) screened at Sundance, gathered critical acclaim, and remains a cult classic of American cinema. Then she went back to school and completed a different thesis. Today, as a testament to her achievements since, a major survey of Smith’s work is on view at MASS MoCA through early 2020.

The following is an edited transcript of a conversation that took place in June 2019 in Smith’s studio, a shared compound in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles.

Cauleen Smith: I went to UCLA in ’94, in the film department. I didn’t go to art school. I left in ’98 and then got my degree in 2001. You know, you have to turn in a thesis film and do these other things—I just didn’t do it. And then I needed the MFA. I needed the papers so I turned in a thesis film called The Changing Same. It’s this very oblique, tragic, science fiction love story: two aliens, doomed on Earth together. It’s a very, very heavy nod to the French New Wave, which is funny to me now. I just keep giggling. I still stand by the film, but the pretenses of being a film student and your aspirations, wearing them on your sleeve—that film is now playing at MASS MoCA. I think that’s the oldest piece in the show.

Still from The Changing Same, 2001, 35mm, 9 Minutes and 30 Seconds.

Travis Diehl: Where were the aliens from?

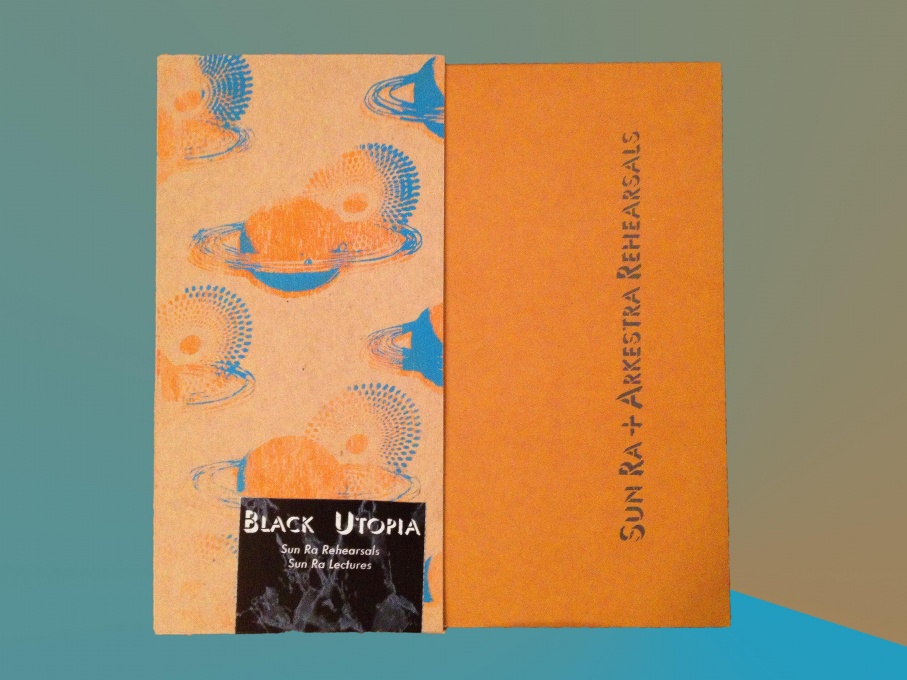

CS: Oh, an undetermined mothership. I guess it never occurred to me to figure out where the aliens were from, because for me Afrofuturism always has been this really useful metaphor for the blank spots in the narrative of the African slave trade. Lots of people have no idea where they’re from. I mean, Sun Ra was really clear about where he was from: he was from Saturn. But yeah, my film was much more about the ship and them trying to find some place to land, having traveled a long time.

TD: I wanted to talk about the Afrofuturist aspect of your work: Is that something you identify with?

CS: When I discovered the term back in the mid-’90s I was so excited that there was a word for this thing that I was interested in. For quite some time—before it became a kind of pop culture, academic fashion accessory—Afrofuturism was this incredibly diverse, divergent conversation, and no one was really staking a claim. It was much more about playing with ideas, thinking about the body and technology and race and history and memory—and distance. Cosmological scale, speculating into the future. It was really fruitful terrain. Now you can take Afrofuturism 101, and frequently that consists of some professor playing Beyoncé and Janelle Monáe videos. It’s gotten kind of pathetic. There’s some notion that, if you’re a black person, you strap on a spacesuit and somehow this is Afrofuturism.

TD: How was your thinking different?

CS: I was thinking of it much less literally, even though I did make a film with aliens—but for me it’s not really about pretending you’re in space. Science fiction is not necessarily even about the future, more like: If we step sideways, what happens based on what we know about ourselves now? As opposed to talking about reincarnation or ghosts or your feelings. It’s not about those things, for me. But it makes sense to just look up Mark Dery’s 1994 essay for not only a definition but the original coinage of the term that he applied along with Greg Tate and Tricia Rose.

TD: I wonder how you feel when Sun Ra says he’s from Saturn. How seriously or literally do you take that?

CS: Oh, I take him really seriously. He was using that declaration to point to the society that he’d been born into, which is basically a society that made him an alien. Instead of this being a position of victimization he turned it into a situation of resistance. You know, it wasn’t until months before he died that he acknowledged he had a sister in Birmingham, Alabama. He was really into the esoteric and the occult, and he would do these deep dives into numerology or hieroglyphs or whatever—he tried to learn Sanskrit. He took it seriously. He made everyone who worked with him take it seriously. So, I take it completely seriously.

TD: As a way of formalizing gaps or breaks or distances, like you were saying.

CS: Or imagining different ways to practice culture.

TD: I think a lot about what Miles Davis said about Sun Ra, that he was a “sad cat.”

CS: Well, Miles Davis hated everybody. I mean, who did Miles Davis not hate on?

TD: But isn’t there a way that even avant-garde jazz in Sun Ra’s era didn’t include him or understand him, to some degree?

CS: There’s so much more to the practice of black music than what record companies, and academic music historians have deemed valuable. I think that, If you look at the hard bop lineage, which Miles Davis came out of before his fusion mode, I would say that’s definitely true. They dismiss pretty much any musician I find interesting. That would include Alice Coltrane, Lonnie Liston Smith, Wadada Leo Smith, and the entire Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians. I could presume that Miles would think they’re all really sad because they’re not rich and successful like him. And they’re not doing this super macho jazz thing. I mean, jazz has always been super hetero, performative, homophobic, especially bebop. But Sun Ra was really successful in challenging what a jazz man was supposed to be. He was decades ahead of his colleagues. Also, while Miles was saying that about Sun Ra, a lot of Miles’s peers were not. Sun Ra’s the artist’s artist or the musician’s musician.

Cauleen Smith, Black Utopia LP (2012)

TD: How did you get into filmmaking?

CS: Kind of by accident. I took a film class at this one school that I dropped out of, Chapman College, which is now Chapman University. And I really loved this thing called “film aesthetics,” which is the grammar and syntax of film. Once that language was decoded, I understood my problem with movies. I’d always enjoyed them and also had been really repelled by them. When I understood what they were really saying, I was like, “Oh, no wonder I hate these movies—these movies fucking hate me.”

TD: Is that why you wanted to make features?

CS: Yeah. And also, it was the early nineties, when all these white dudes plus Spike Lee were blowing up with $7,000 films—it seemed possible. I didn’t realize their films were actually much more expensive than the numbers that were being thrown around. I just thought this is a good time to get in here and participate in this conversation.

TD: What ended up happening?

CS: I made a feature and got my agent and my lawyer and started working in the film industry and did that for five years and got absolutely nothing done. I was constantly in the room with people who were wasting my time or I was wasting their time. I wasn’t making anything and wasn’t ever talking to people I wanted to talk to, which is the only reason for me to make stuff. You start to realize you’re really in the wrong when you’re not even able to respect the system that you’re working in.

TD: Would you say you made experimental films?

CS: Even at UCLA that’s really what I was doing. On the side, I would deliver the narrative thing and then I would what I wanted. Or, I would sneak something experimental into the narrative thing and the students would be like, “You do realize that you put the sound of swimming, but the guy was walking, so it should be footsteps.” I should’ve known then. Once I started teaching at UT Austin, I was puttering around, making my own stuff while teaching experimental film and Super 8. The friends I made were artists, and I found myself migrating towards that—the way that you can talk to artists about ideas in great depth, trying to push an idea as far as you can. Almost like art is philosophy, but in a material realm. I found philosophy and language and post-structuralism really oppressive and alienating, so I was excited when someone could take some idea from this theoretical world that I was wrestling with and show it to me in another form. The conversations I would have when I showed those experimental films were so much rich than the conversations around narrative film. Black film, in particular, was understood as a way for white audiences to learn about black people. Black films were understood in the independent film world, as sociological tools. In narrative film, people ask you the most soul-crushingly stupid questions: “So did so-and-so really go to the store in that scene? Or was she just dreaming of going to the store?” They want answers to the story, because everything’s handed to them anyway. When you take narrative away, people have to deal with what’s there—if they choose to do that, they’re already willing to wrestle with it themselves.

I also really enjoyed making my own props for films. Then, when I would listen to artists talk—when you talk about a narrative film, you spend a lot of time sharing war stories about how this amazing shot happened, or whatever—they would talk about some very specific exchange that they would produce out in the world. And that’s what I do—that’s what a filmmaker does just to get a shot. That was this entirety of an artwork. All of the sudden I was like, “Oh, am I doing social practice when I make a film?” When I make a film in Oakland and I don’t have any money, I have to talk to everybody on the block. I have to negotiate what color I’m gonna paint the house so that it doesn’t piss them off. I actually have to find something to do with their kids because it’s summertime and they keep showing up on the set. Now I have to get my gaffers to apprentice eight-year-olds, and then I have to pick up extra free bagels in the mornings to feed these rugrats. I started to think that I can unpack what I do when I’m making a film. I started to think about not throwing my props away. Sometimes I would start making a film and make the props, and then I wouldn’t even feel like making the film anymore.

TD: Something that struck me about your feature, Drylongso, is the main character: she’s in a photography class and making photographs throughout the whole film, but what she ends up creating is this kind of sculpture garden in an empty lot in her neighborhood. And there’s a party—

Still from Cauleen Smith’s Drylongso, 1998, 16mm, color, sound, 82 minutes.

CS: Yeah, where she feeds everybody.

TD: She feeds the neighborhood, so even at that early stage your main character is more or less engaging in social practice.

CS: That’s really obvious, but at the time that was just a cool way to end the movie. Now it’s really endearing for me to watch that scene and think, “Oh, that’s what I do now.”

TD: Do you still have some of those props—sculptures—from the film?

CS: No, all are lost. They all got dismantled. What do I have? I have a lot of the Polaroids. And I have the camera, which I actually ended up using as part of the installation at MASS MoCA.

TD: Do you work with non-actors in your films?

CS: I actually love working with actors, when I have something that’s meaty enough for a skilled performer. But usually I’m dealing with a figure as an avatar—as a placeholder for whoever’s watching—so I’m usually trying to keep people from performing. An actor has all of these skills and I’m like, “Don’t do any of it. Do nothing.” So, why not just cast someone who naturally does what you want them to do? When you tell them to just sit there, they’re more than happy to do it. And they don’t ask why.

TD: In Remote Viewing—the piece where the excavator digs a pit and a bulldozer pushes a schoolhouse into it—there’s a quick shot of two figures, a boy and a woman, standing against a green backdrop that mirrors the huge scaffold draped in green behind the schoolhouse. Though you wouldn’t really say there are characters in that film: Who are they?

CS: I wrote out an entire narrative for that film, based on a memory of a man who’s now in his seventies remembering being nine years old. He describes this schoolhouse being pushed into a hole. He still remembers it as a nine-year-old, but there were all these blank spots: How did his mom know the school was getting pushed into the hole? He didn’t think to ask. Who told her? All the sort of machinations in the story: What does it mean to be in a town where they’re going to bury your schoolhouse underground? I was just speculating, so I wrote a script and storyboarded the whole thing.

Excerpt Clip from Remote Viewing, 2011, digital film loop for projection, color/sound.

For one, it was really expensive to bury that house underground. We had to find a place to do it. Dig a big hole, build a house, and then bury it. A lot of resources went into that. And then, once I did that, I was not sure what else needed to be said. Or, I wasn’t sure how appropriate it was, or what difference it made, for me to make up a story about how this happened. It simply happened. Plus, the giant greenscreen we made on scaffolding became a thing. That was the first thing I’ve ever made where I was like, “That’s a thing. I’m done. If we don’t shoot at all, I just built this cool thing—look at the sun hit it and change it.” It was a turning point film in that regard.

TD: Did you have plans to actually use the backdrop as a greenscreen?

CS: At first, I thought that I would use it to slip the schoolhouse in and out of the site. And then I thought it was actually good to have it there to cue people as to this being a total reenactment, a site/non-site kind of thing.

TD: That makes me think of a quality in a lot of your films: it’s film, it’s indexical, it’s this representational image. But what’s happening feels very abstract, or symbolic.

With H-E-L-L-O—the project you did in New Orleans with the musicians playing the theme from Close Encounters of the Third Kind on bass clef instruments—the musicians are placed in really specific locations, but, for me at least, it’s hard to tell what is what, let alone the significance of these places. How do you deal with that gap?

CS: A film has to be watchable without knowing all of the mini-meta-layers. In narrative film, everything is supposed to be in there for you, and if it isn’t then that’s a flaw. I want to work in resistance to that: should you encounter this information later, it’s an augmentation, an opening based on the experience that you’ve already had as opposed to the one I’m telling you to have. How the places were chosen is available, at the end of the film, should you want to dig in. Or, if you’re from New Orleans, the places might mean more. Knowing that was where H-E-L-L-O was going to be first, I was kind of making it for the people of that city.

H-E-L-L-O. 2014. Digital Video. 9:55. Dir: Cauleen Smith

TD: I wonder if that’s a tendency in contemporary art as well, to surround a piece with didactics to make sure everyone knows what’s important, even if the work doesn’t give that info.

CS: It’s funny, I keep having conversations about didactics. I’m kind of a self-taught person, so I rely on didactics. It doesn’t matter what it is. It could be a painting of a lady: I’m like, “Why would you paint this lady?” Thank god there’s a didactic to explain it to me. Just because I can tell what it is doesn’t mean I understand what I’m looking at. I always think of art as being contingent on the context, and someone has to offer that to you.

TD: That makes me think of the banners that were in the 2017 Whitney Biennial, In The Wake, and some of the other banners you’ve made for different processions. You call them “processions,” rather than a parade, or protest.

CS: Some are processions, some are flash mobs.

Raw Footage from In the Wake procession

TD: Flash mobs?

CS: Uh-huh. The processions are always protests, they’re just not in service of anybody’s political machine.

TD: Which has to do with the texts on the banners: on the one hand, they’re really direct and sort of tell it like it is. But there’s another way that they’re—cagey isn’t the right word . . . poetic? What they say is clear, but the politics of that message isn’t as clear as the phrase.

CS: It’s always about the you, and the I, and the who. And that can shift. It’s interesting how a lot of the banners have gone to institutions, and a lot to individual people. Then I think about what it means to live with an object like that, and how crucial it is that the I and the you are always undetermined or ambivalent.

TD: As poetry does: turn the speaker around, turn the address around.

CS: Probably where I learned it, yes. It’s crucial that, either coming or going, the banner’s meaning holds that same weight. On the other side of each banner are all these symbols. That was really messing people up. They were fine with, “I Can’t Breathe”—they get it. Then on the back would be a crow with a dagger in it, or a diamond in a puddle of blood. And they’re like, “What does that mean?” They had a point: those are icons, or an index of symbols, that you can shuffle like hieroglyphs. I repeat them enough that I’m thinking maybe people can make some sense of them.

Cauleen Smith, In the Wake, 2017. Currently on view at MASS MoCA.

TD: I think that’s true.

CS: You weren’t that confused? Okay, good.

TD: You rearrange them. They reappear in different combinations, or different levels of violence.

CS: Different levels of gore.

TD: How would you want to contextualize those banners, in terms of didactics?

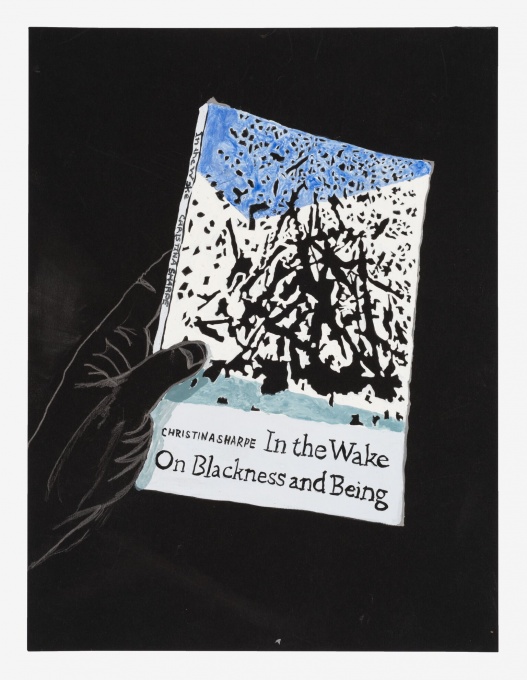

CS: I thought that they said so much—I mean, there’s text all over them. And when they wrote the didactics, it was really about getting them to not say stuff. I wanted people to know that I’d named the piece after Christina Sharpe’s book, and I wanted people to know that the banners were in response to state-sanctioned violence against Black people. And that’s good, right? You can go off and running with that, I think.

Cauleen Smith, BLK FMNNST Loaner Library 1989-2019, 2019, Gouache and graphite on paper

TD: What did you think of the conversation around the 2017 Biennial, and maybe how that has weathered?

CS: The only thing that has changed over time is that now I have a greater appreciation of what the people protesting were trying to do. But my feelings about how they did it haven’t changed. What got hijacked in the conversation was this idea about censorship. People really fixated on that, because that was a lot easier than talking about what they were really talking about: What does it mean to consume Black bodies, to use them as fodder? When Dana Schutz said that her painting Open Casket was an empathetic act because she was thinking of her own son, I was like, “Well, if you were thinking of your own son you would’ve painted your own son mangled in a coffin.” But no one would do that, because that’s obscene. Ergo, maybe this painting is indeed obscene. Why would you take someone else’s son and paint them mangled in a coffin? That’s weird.

It’s a lot easier to defend an artist’s right to say whatever they want than it is to really parse out what it is we’re doing when we go into our studios and decide what we’re going to make, and how much effort that takes. Or, in the case of that particular painting, how little effort. And this is not disparaging Schutz as an artist or as an individual. It’s a tricky thing when you become extremely successful: no one calls you on your shit until it’s way too freaking late. If it’d been, like, twenty years ago, I’m sure a friend would’ve said, “Really? Might want to gesso over that one.” Now, I think the painting is showing in Berlin and showing here and showing there. In Europe, this is a wonderful abstract thought project—“Oh, the tragedy of American racism”—that’s really easy to think about instead of what’s going on in their own countries. That would’ve been a really interesting conversation.

Another really interesting conversation would’ve been to talk about all the other art in the Biennial that was awesome.

TD: Your In the Wake piece addresses some of those exact issues, just in a more oblique way.

CS: There was a lot of work in there doing a lot of interesting work. I’m pretty sure the protestors hadn’t even seen the installation when they launched, they just knew that this painting was going to be in there. That was an interesting, maybe generational, thing. I draw book jacket covers, and I can’t make the drawing until I’ve read the book. So, I wouldn’t launch a protest against something that I hadn’t really thought about. I can anticipate the backlash of . . . maybe being a little bit uninformed.

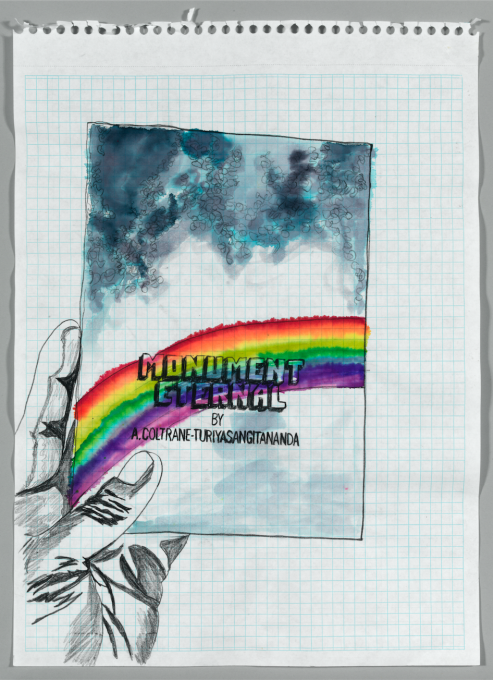

TD: I wanted to ask you about those book drawings, in terms of this question of how to educate, or point to something, like pointing to Sun Ra or Alice Coltrane or these other bodies of thought.

CS: The decision to draw books instead of, say, taking photographs, was that to me there was something about the process of having a book, looking at it, considering it as an object, and then drawing it. The time that took was analogous to reading it. I thought that I could get someone to be more intrigued with a book when they saw it and wondered, “Why would you draw that?” It’s the same as asking why read that.

Cauleen Smith, BLK FMNNST Loaner Library 1989-2019, 2019, Gouache and graphite on paper

TD: You occasionally see a book in an art show that’s just a physical book—a books-on-shelves motif—where it really does seem like a reading list. You’ve titled different sets of the book drawings different ways, right? Sometimes it’s actually called a reading list.

CS: The first one was a reading list. The one at MASS MoCA is a loaner library. The reading list is super pedagogical, it’s me bossing people around: “You should read these books.” I feel strongly about that. But then, there’s the loaner library, which is super personal, maybe even biographical. It’s books that my friends have written, books someone has given me about how to take care of plants, or, you know, my obsession with flying kites. I don’t actually fly them, just thinking about it. These are the books you loan to people because you’re like, “Oh, you’re going to love it.”

For the next list I’m going to do, I started reading all this postcolonial African literature from countries in the process of independence—new countries—really cool, surreal, crazy novels that I never knew about. There’s this guy Camara Laye—I haven’t read anything like this since reading Kafka. So, it’s become more about an opportunity to have a discourse about how to read, what to read, why to read, who to read to, etc.

TD: There’s a way in which that’s prescriptive, but also seems very interior, personal. That’s political, but it’s not quite activism.

CS: Absolutely. Actually, thanks for bringing that up. I’m emphatic about not being an activist, which is why I was a little shocked to be on the cover of Artforum with the title “Art and Activism.”

TD: You made banners.

CS: “Hey. You’re protesting.” Normally, they put the names of the artists in the magazine on the cover. This time they didn’t—no names, just “Art and Activism.” And then there’s my banner, which is the quote from Alice Coltrane, of all things, and it’s something she claims God told her. It’s not a protest, it’s a prayer.

I actually think that protests are beautiful art forms: the signs, the sounds, people walking together, the ebb and flow. They’re complicated, because there are all these different energies meshing, agendas conflicting, jostling for space, potential for violence. I’m using all these devices and strategies, but I’m trying to do something a little bit less like grasp at power and more like touch people. I know what I’m saying, but I’m not trying to organize a protest—if anything, it’s about atomizing something instead of consolidating. I know that sounds corny, but it really is different: I’m not trying to get this, I’m actually trying to get you.

TD: That feels very contemporary to me. Thomas Hirschhorn, for example—a lot of formal similarities—likes to make big books, or, sorts of monuments that involve “the community,” but there’s a different tenor to it. With Hirschhorn you’re very aware of what you’re supposed to learn, or how you’re supposed to feel when you come out of it. But you don’t really make those determinations.

CS: I spent this past year doing a research project with Robert Bird, a professor at the University of Chicago. He’s a Slavic languages expert and foremost authority on Tarkovsky, the filmmaker. We were looking at revolution and film: Can film incite revolution? How is it used to do that? Of course, you look at Russia, and that got me thinking about communism in America—and Black people, we used to be communist. I didn’t know, because now we’re just rabid capitalists and crazy neoliberals. But it’s not really working out, so maybe we should go back and look at this other idea we had, which is like, public schools and basic human civil rights for everybody. Maybe we should go back to that, instead of “I’ve got hot sauce in my bag.” I’m looking at all these women in the early ’20s and ’30s who were communists, looking at their lives, and trying to figure out if I can make a series of films that look at ideas about communism, if it can be resuscitated—maybe even come up with a new word for it.

TD: How do you feel about the word “socialism”?

CS: I mean, all these words undermine the conversation that’s possible. I love the idea, but it freaks other people out to the point where they can’t hear you anymore. That may be the main reason to try to come up with new ways to describe possible systems. Because the names that we have, we just spent the last century fighting wars over this shit. I think socialism’s awesome. I think we should do more of it. But there are people who would rather gnaw off their hand than let that happen. So, maybe if we call it something else, they won’t notice.

TD: I think it’s worth a shot. Which reminds me—could you talk a little bit about We Already Have What We Need, your new installation at MASS MoCA?

CS: That came out of my many circuitous bike rides on the South Side of Chicago through miles and miles of empty lots and abandoned houses and neglected storefronts. The psychological impact on a community when there’s a refusal to invest or support what’s there—it makes you feel as if you lack. But, actually, we don’t lack. The empty lots, especially in the springtime, were so alive and rich. I’m from California, so I didn’t realize that I was riding by prairies. That’s pretty sexy. There’s a mile and a half of prairie in the middle of a giant city. It’s an ecosystem: there’s little bunnies and coyotes, and the empty lot that the kids cut through to go to school is full of flowers. There’s full-on sunlight. I started to fantasize about, well, all of the things that are possible here. And not like architects do, where they just take the space and do something with it. You don’t have to do much, all you need is a few boxes on a neglected corner, and people would start a garden. I was like, “That works.”

We Already Have What We Need, Multi-channel video installation at MASS MoCA

How do we start to understand that we don’t need more, we just need to do more with what we have? And then, what do we have? I was listening to some of my students talk about trying to get testosterone, and how crucial it is. You can’t just go on and off, it makes you so sick. That’s a need. That’s real. Why is this hard? This shouldn’t be hard. I was making these weird little arrangements on tabletops that were trying just to look at what we have, how do we have, how do we live, what we are remembering, what we are forgetting. The least mundane objects would be the African figures that are mostly from the Ivory Coast, but everything else is from the Goodwill, from my backyard, my friend’s backyard.

I’m very interested in race, gender, and class, but at the end of the day I’m most fundamentally concerned about the planet and the way in which human beings refuse to understand that we have to take care of it. Blows my mind, because this planet could kick us off at any moment—seems like she’s trying to. And wouldn’t it be better if we just lightened up our footprint a little bit? So, what do we really need? We need to not piss off the planet. We need to behave.

TD: Right. That’s a need.

CS: It’s a definite freaking need.

Cauleen Smith, In the Wake, 2017. Satin, poly-satin, quilted pleather, upholstery, wool felt, wool velvet, indigo-dyed silk-rayon velvet, indigo-dyed silk satin, embroidery floss, metallic thread, acrylic fabric paint, acrylic hair beads, acrylic barrettes, satin cord, polyester fringe, poly-ilk- tassels, plastic-coated paper, and sequins. Sixteen components, 60 × 48 in. (152.4 × 121.9 cm) each