Artists at Work: Kenneth Tam

by Natilee Harren

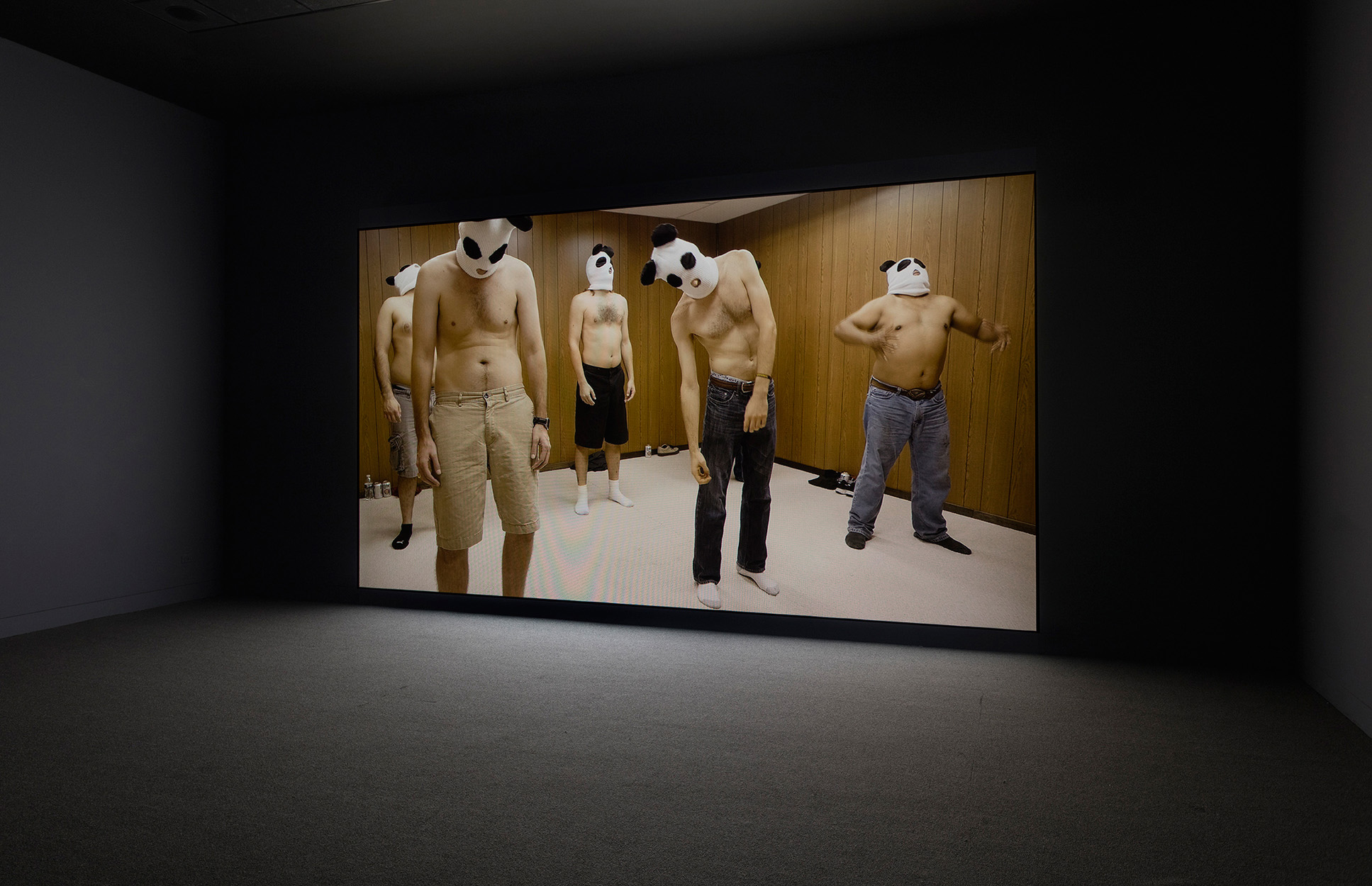

Kenneth Tam, Breakfast in Bed, 2016, single-channel HD video, color, sound, 31:54 min. Installation view, Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only, June 12–August 28, 2016, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Kenneth Tam (born 1982 in Queens, New York) works in video, sculpture, and photography, using the male body as a starting point for discussions about performance, physical intimacy, vulnerability, and private ritual. His practice, which often begins by recruiting collaborators online and enlisting them in face-to-face encounters, is oriented around creating situations that reimagine the social space of and for the male body in ways that challenge received ideas about masculinity and behavior in general. Tam graduated from the Cooper Union and received an MFA from the University of Southern California in 2010. A recipient of an Art Matters Grant and a California Community Foundation Fellowship, Tam has participated in group shows and screenings across Los Angeles. His work is included in Made in L.A. 2016 and has been the focus of solo exhibitions at Night Gallery (2013) and Commonwealth and Council (opening July 30). The following conversation took place in April 2016 in Tam’s studio in Houston, Texas, where he was in residence as Core Program Fellow at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, preparing a project for Made in L.A. 2016: a, the, though, only.

Natilee Harren: One of the first things we could talk about, Ken, is that we’re sitting right now in a studio within a studio. Inside your workspace you’ve built a fully enclosed video recording studio with wood-paneled walls, carpeted floors, and a partial drop ceiling. So we’re sitting in a box within a box, and this box is part of a video project you’re working on now in preparation for Made in L.A. 2016. Can you talk about this piece, Breakfast in Bed (2016), and how the space we’re sitting in now operates as an architectural container for it?

Kenneth Tam: The way I originally conceived it was that I wanted to look at how men behave in groups by actually creating my own sort of men’s social club. I used the Internet to enlist the help of seven men to come into my studio—this box, actually—and engage in activities that I created for them. I was really interested in how men need a space to retreat to in order to express intimacy or affection, which always have to be mediated through some sort of other activity, be it cigar club or model railroading or religious retreat—any activities that are ostensibly about a shared interest but are ultimately about male-to-male intimacy.

I came up with activities that I thought would be challenging for them. A lot of them involved physical intimacy, which is a through-line in my work. I’ve put myself in positions of incredible vulnerability or intimacy with total strangers, and I wanted to have these men experience that with each other. It’s also important to say that I paid them for their time, and they were all unknown to each other at the start. It was kind of a social experiment to get these random strangers in a box and see what happened. We shot nine weeks of video. There were seven consecutive weeks, and then we took about a two-month break, partly for the holidays but also so that I could look at my footage and think about what else I wanted to do. This was ultimately edited down into a 32-minute video that will be projected in a black-box gallery at the Hammer Museum.1 While the actual set from the video won’t be a part of the installation, I want the experience of watching the work in the gallery to approximate the feeling of being in that room.

Kenneth Tam, Breakfast in Bed, 2016, single-channel HD video, color, sound, 31:54 min.

NH: Among the important frames you’ve constructed for the project are not only the physical, architectural frame of the box and the social frame of normative masculinity, but also the economic frame you’ve engaged by paying these men for their time, along with soliciting participation via online systems of economic and labor exchange—another important structural backdrop for the project.

KT: Absolutely. For all my previous videos I primarily used sites like Craigslist to find people to work with. I’ve always been fascinated by these kinds of Internet spaces and the way interactions start off as anonymous social encounters but oftentimes end up in very physical, intimate experiences. I was interested in the randomness of it, the way you can encounter people you never normally would in your everyday life. There is an arbitrariness that cuts through class and social lines. It felt like a truly democratic kind of open space. But that turned out to be less and less true the more I used these sites and began to realize that there are only certain kinds of people who inhabit these spaces, ultimately.

NH: What kinds of people?

KT: This project required a certain level of commitment that I had never asked of my participants before, and I could immediately tell that the people I was meeting through Craigslist were not going to come back after one encounter. Craigslist’s exchange culture is geared toward immediate transactions or gigs, be it the selling of goods or labor. Everything is short term and based on satisfying immediate needs, which is also how things function in the more erotic “casual encounters” section. So I put an ad on Reddit and that’s how I found most of the men I ended up working with. There’s a very different demographic at play in the two communities, and I wasn’t really aware of that until well after the project began. The space of Reddit is primarily a white male one, I found out. Some estimate that 60-70% of all Reddit users are male. You can sense that in the kinds of humor and the way people talk, and the thread of misogyny that runs through a lot of the discussion boards. I don’t necessarily think that’s apparent with the men I ended up working with, but those sorts of things are embedded within the backdrop of the project as a whole.

NH: Reddit is an appropriate online community match for the project because you are indeed exploring modes of masculinity and masculine intimacy and identity—but not your own specific identity, it seems. In contrast to another recent interview you shared with me, in which the interviewer pushes you to talk about the role of your own racial and sexual identity in your work, I am struck by how much your work, and this project especially, seems not to be about your own identity at all.2 You’ve taken yourself out of the picture altogether.

KT: Right.

NH: In earlier work where you do feature as a visible performer—for example, The compression is not subservient to the explosion; it gives it increased force (2011), which also features a box—the videos seem to reveal more about your collaborators, often white men who try to manipulate you or control you, than they reveal anything about you.3 But I suppose I should ask: What role do you see yourself occupying in these filmed actions? What does it mean to be behind the scenes when in an earlier moment you had been so very visible?

KT: That’s a really good question. A lot of the very early works were experiments—me dipping my toes into Craigslist and showing up at someone’s home with a camera and not even doing anything. Those early videos, like Cathy (2009), were about injecting myself as a physical presence in a situation without having to actively do much and then seeing what rupture, if any, could happen.4 I was thinking about a lot of 1970s conceptualist performance. What if I just put myself in a situation where I didn’t belong? Would that be enough to create something without me even having to do anything else?

NH: Who exactly were the artists you were thinking of and inspired by?

KT: Adrian Piper—her early works were really important and influential to me—along with VALIE EXPORT and Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Those were the three I thought about a lot. Chris Burden and Vito Acconci, too. Acconci’s work is way creepier, way more masculine, using machoness as a way to disturb. I suppose I was always interested in what female performance artists could do with minimal effort or minimal action, and how they allowed themselves to be vulnerable in a way that a male performer never would. Burden and Acconci put their bodies in highly vulnerable positions, but their actions also seem incredibly aggressive and so much about their own sexuality and being in control.

NH: You’re right, most of the models for that kind of performance practice are women. I think also of Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece or Marina Abramovic’s Rhythm 0, both works where a woman performer presents her body in a way that is either completely passive or kind of passive aggressive. In either case, the artist uses a passive subjective stance to test social boundaries and behavioral limits.

KT: Someone once described my early works as capturing very short moments of social intensity. I started making these videos when I was in grad school, not really understanding what I was producing. There was a mixture of embarrassment and a little shame, like, “What am I doing?” [Laughter] A lot of these things were very impulsive and I didn’t necessarily have the conceptual framework for understanding what it was that I was putting myself into. I wasn’t even sure if this was art or not. But there was enough conversation happening, as I was making these things, to push me to be more daring in terms of what I was willing to do. I think that’s what led to these more collaborative works. I realized that is the most interesting thing these videos could be about—unleashing unseen, unusual potentials within social encounters and letting them unfold in their own way.

NH: There’s a dynamic in your work of pushing boundaries and then, in these moments of intimacy between pairs and now small groups of people, we witness people establishing new rules of engagement that are immediately humorous, entertaining, and absurd. But then there’s also an intense erotic charge to the work, whether you’re dealing with groups of men or with yourself in collaboration with others, both men and women. The erotic dimension becomes very poignant and maybe even posits some kind of alternative ethics of being with other people.

KT: Or of understanding the body. There is a new relational space that is allowable for that span of time and whatever rules we set for ourselves, in terms of personal boundaries and what can or cannot happen between two bodies, are momentarily disregarded for the sake of experimentation.

NH: Speaking of possibilities and potentialities, it’s important to establish that the reason that space of possibility can exist is because you’ve carefully constructed the frame in which it can unfold. Again I would point us to this wooden box we’re sitting in, which is so important. It’s like a hole cut in the fabric of the universe, enabling these men you recently worked with to get outside of their normal habits and engage with one another freely. There’s also the necessary ingredient of quasi-anonymity achieved through the Internet recruitment frameworks you’re using, enabling connections with people who aren’t part of your immediate social network. What’s furthermore amazing to me about this space is that it doesn’t have any windows. That’s probably for more practical reasons, but to me it reinforces the sense of this space as a space apart from the everyday.

KT: I had always conceived this as a basement space. What’s funny is that I didn’t realize that Houston has no basements, so even in the location where I wanted it to exist, it could not be found. It truly is a space apart from reality. I wanted the men to use it as an excuse to abandon their daily selves and to engage in something that they probably never have the opportunity to participate in otherwise, almost to the point of role-playing. There are actual role-playing exercises in the video, but I never encouraged them to be someone else, necessarily. I just wanted them to expand what they could be with these other men, to remove the straitjacket of masculinity. The way the male body is codified in our society is so heavy. Our behaviors are so prescribed and the way we look at other men is so problematic, too. This was an opportunity to remove that protective layer—for two hours a week, at least, for these nine weeks.

Kenneth Tam, sump, 2015, video, color, sound

NH: Can you talk about some of the exercises you had them do? What were the first things they started with? And how did those open out onto further exercises you had them try?

KT: The very first thing they did on week one came from the video sump (2015), which I had just finished with my father. There was one scene in that video where he appears in a closet, his face covered in Cheerios.5 There’s no context for why he’s covered in Cheerios. Then all of a sudden you see me walk in with the same sort of adornment. When I was preparing for that scene with my father, I found that applying these things to his face was a really intimate gesture. It required me to be next to him for an hour or so. Him topless, sitting in a chair, not moving, me pretty much the same way and touching him, touching his body. The experience was quite moving and loaded.

NH: But in sump we just see a shot of him. You don’t show the action of applying Cheerios to his body.

KT: Right. And so in doing that piece I realized that the act of preparing for this thing was far more intimate and weighted than the final image. I thought, wouldn’t it be a nice way to have the group get to know one another by having them perform this act? So that was the very first thing they did. It was my perverse version of an icebreaker.

NH: Well, it worked! When you were earlier talking about how men typically get to know one another through hobbies, that’s definitely the nature of the conversation they’re having. They’re not fishing, they’re not playing cards, they’re not playing golf or any kind of typical male activity—they’re gluing Cheerios. It’s actually the conversation that in this case normalizes the bizarre activity they’re doing.

KT: Exactly. This is the moment when you learn the most about them. If you listen carefully to the whole dialogue they’re having, they’re sort of feeling each other out. They’re doing this very strange, intimate activity that they’ve all volunteered for, but they’re also doing their best to play it cool.

NH: They immediately begin to talk about their girlfriends and their marriages.

KT: Yes. Very quickly they start talking about things that reinforce their presumed heterosexuality, or one can interpret it that way. This is the most biographical information we get from them, as it was the only opportunity they had to socialize in a sort of normal way, I guess. There was a sort of ritual taking place but talking was the real activity.

NH: The activity was meditative and there was an element of care to it. In that sense it’s actually very different from the other activities we see them do, which are more game-like in nature and involve less dialogue. Can you talk about some of the other activities?

KT: There are definitely a lot of games. I was researching activities that happen at church retreats or other events where hundreds of men get together and abandon their families for a weekend, ostensibly for religious fellowship; but it’s really just these romps in the woods where they play as a way of displaying affection for each other. A lot of these games also dovetail into corporate team building exercises.

NH: Which is another evocation of these wood-paneled walls.

KT: Yeah, the drop ceiling definitely evokes office decor or architecture. What I realized about a lot of these activities, too, is that they allow their adult participants to assume very childlike subjectivities and engage with each other in a less rigid way, to trust each other, to develop bonds of intimacy or to be vulnerable around each other. And so I adopted some of those characteristics in designing the activities. There were a number of games, as well as some role-playing. There was one scene where I asked them to speak in the voice and manner of their mothers, to assume this other subjectivity. And on multiple occasions I had them do something I initially conceived of as “complimentary whispering”—just going up to someone and saying nice things to him, but very close up and in a soft voice.

NH: Those are the most amazing passages in the footage I’ve seen. That is where this sense of an alternative space of male intimacy really gets established. You began to see the participants just as human beings.

KT: You understand the real challenges that masculinity presents. Simple articulation of an honest feeling—that was the most difficult thing for most of these guys to do. They just couldn’t do it in a casual way. A lot of it was contrived or they had to make a joke of it. They couldn’t say how they felt in a straightforward manner. When they did, it was always so awkward but also so revealing. The final version of that activity was to just have them describe each other physically. It didn’t even have to be complimentary, just “look at this person and tell me what you see.” That proved to be such an amazing challenge.

NH: Was it part of your call for participants that they needed to be both male and straight?

KT: No, I made no requirements in terms of sexuality. In fact I didn’t bring it up. I never asked them about it because I didn’t want to bracket whatever they were doing in that sort of binary. I’m very careful about describing my own sexuality or the sexuality of my participants because I feel that language could hinder the potential of what these encounters could be. I didn’t want it to be framed within the dialectic of hetero/homo.

NH: I’m really interested in that line of thinking in your work because—and I think you might agree—it contrasts with the turn in the larger cultural discourse right now toward hyper-identitarian positioning. The celebration of diversity that our generation (born in the 1980s) was raised on has calcified into so many separate identity cul-de-sacs. In the United States, at least, there is a fixation on drawing separations and policing boundaries around identity. But you seem more interested in unfixed modes of identity, which I suppose on a theoretical level could be read as queer; there is a desire to maintain a sort of openness, a kind of fluidity. This draws me back to the notion of a neutral subject position you try to maintain. What becomes of the space of possibility for human relationships if they’re not pressured by a demand to be organized in a certain way?

KT: I think another word to use here is generosity. I allow the people I work with to explore something without having to identify it before it’s experienced, without forcing it to conform to any ideological frame—not even a frame as broad as sexuality. When I started doing these things—when my participants were becoming only men and I began getting into these somewhat erotically charged situations—I was really unsure whether this was the kind of work I wanted to continue doing. I wondered, “Does this start implicating my own sexuality? Do I want the conversation to be about myself?”

Kenneth Tam, The compression is not subservient to the explosion; it gives it increased force, 2011, video, color, sound

NH: Typically we expect the artist to instruct his or her performers on what to do but here we have a model of performance that, as you described it, is more about creating a framework for interaction that is radically unscripted. And with that comes an intense potential for the work to move in a direction that you didn’t anticipate, and certainly the potential for failure.

KT: That’s the entire premise for the box video [The compression is not subservient to the explosion; it gives it increased force]. I placed an ad with a very specific project in mind, and I received a request from a man to do something rather different. After much back and forth, we came to an agreement on how we could meet each other halfway with our respective projects, and produce something for the camera that was unscripted and appealed to both of our interests. The video continues this negotiation, with the man continually testing my boundaries while I maneuver around his requests.

NH: So though this was more collaborative, the box is yours. All the boxes or frames for the encounter are yours.

KT: Right. I maintain the parameters of the situation and I still have authorship over the editing and ultimate authority over the project. But I do welcome a sort of—I wouldn’t say hijacking of the project, but I do welcome the non-violent but very sudden interjection of someone else’s desire, libido or what have you, thrust upon me. That’s a very rare thing to encounter: someone unafraid to exercise their own ideas and to take my project into an unexpected but still interesting place.

NH: You’re deliberately courting transgression. I use that word specifically because the title of the work comes from Bataille’s essay on transgression.6

KT: That’s what I was reading at the time.

NH: I’m curious why that text became of interest to you, and if it’s still a driving force in the work you’ve been doing with this group of men in Houston.

KT: I think all my videos probably up to that point, and even a little after, were about some sort of transgression into a certain normative social space. Entering into someone’s home, bringing a camera, disrupting a dinner, asking someone to shave me—I thought of these as slight transgressions that could provoke with nothing else but my body. My body is in the wrong place or not doing the right thing, usually within the private space of someone’s home. Transgression often has a violent, negative connotation to it, but I think that what I do is still transgressive even if it’s playful and humorous and absurd. Any simple disruption is a generative transgression. Seeing the group in my current video struggle with the language to describe another man’s body—I thought it was so revealing and moving. I think those are transgressions, too, in a very subtle but important way.

Kenneth Tam, sump, 2015, video, color, sound

NH: Breakfast in Bed seems to me the perfect complement to sump, where we see you playing out a bunch of invented rituals with your father, who takes it all very seriously as if in duty to you. In this new project, you’re dealing with a similar set of issues—male intimacy—but you’ve expanded your concern beyond the biographical, and you’ve put yourself out of the camera’s view. The subject now becomes a version of mainstream masculinity, mostly of white middle-class men living in Houston, Texas.

KT: Ostensibly middle-class men. Their backgrounds are actually much more diverse than that. In terms of their screen time, though, they do come across that way.

NH: I wanted to ask you about the one man who is Latino. His identity is highlighted at certain points, for example when he sings a song in Spanish to accompany a kind of conga line dance, or when he’s the only man who keeps his shirt on for an activity. In the conga line, he doesn’t actually grab onto the waist of the man in front of him. These moments show the different limits of what his personal sense of masculinity allows for.

KT: That man, Gilberto, was really great to have. And just to be clear, Niko is also Latino, which is not always apparent to the audience. I think Gilberto brought so much to the dynamic that the other men couldn’t. It was really interesting to see how he negotiated his otherness very carefully in relationship to these six other men. Clearly he’s not fluent in English, and that perhaps limited how expressive he could be, but he more than made up for that in terms of physicality, in terms of being vulnerable, in terms of just plain enthusiasm.

NH: As a female viewer, the project is particularly interesting in that it allows access to an intimate space of male relationships that I typically don’t have access to; although admittedly it is artificial, constructed by you. Just seeing moments of interpersonal awkwardness between men, who are automatically identified with power in our culture, is rewarding and some moments are really beautiful. The men beg the viewer’s sympathy.

KT: The way I conceived the space was not just to create a clubhouse for them but also, symbolically, to create a space where they could come in and do these intimate, vulnerable things without necessarily compromising their day-to-day selves. They could come here and dance topless with other men but leave and not feel embarrassed or whatnot. This was a space where they could activate untapped dimensions of themselves within a certain privacy, without judgment, and see what happens within this other way of being with other men.

NH: Typically we understand habits and rules and social codes as constricting behavior, but through masks and costumes and externalizing, or sometimes anonymizing, the source of instructions—having another voice tell them what to do—the men follow rules that guide them beyond normal, socially acceptable behaviors. The trope of the box in your work is, then, ultimately misleading. You establish the box only in order to break out of it in certain ways. Perhaps it’s important to point out again that the box we’re sitting in right now actually doesn’t have a ceiling. [Laughter]

KT: Right. There is an escape.

Kenneth Tam, Breakfast in Bed, 2016, single-channel HD video, color, sound, 31:54 min.

NH: We should recall as well the cardboard box at the center of The compression is not subservient to the explosion; it gives it increased force, where the inhabitant immediately starts cutting holes in the box. So the box is the place where you start, and then the work is about figuring out how to break out of it.

KT: Definitely. It’s a space to exceed very early on. It’s not meant to limit. It’s actually supposed to be generative.

NH: We’re back again at Bataille: “The compression is not subservient to the explosion; it gives it increased force.” So your Houston group, has it disbanded?

KT: As a group, they’ve definitely disbanded, but individually I still keep in touch with a few of them. I saw one of them last week. I’m not sure if we’re friends. I guess we’re friends. Yeah, we’re friends now that we’re out of this weird semi-employment or whatever relationship we had before—or participant/director, I don’t know. After having done all this stuff and spoken to them, I still don’t know.

NH: It seems meaningful that even after these many weeks of working with them, there’s still an ambiguity about what your relationship is.

KT: Definitely, because I’m so outside of their world and they’re so outside of mine. I could easily call them friends, but at the same time I feel like there is a sort of chasm in terms of our experiences that cannot be bridged. Maybe I’m shortchanging the relationships, setting parameters up for what this can or can’t be. I always question how they see me. I can only imagine what I am in their eyes. Maybe I’m ultimately just another guy.