Artists at Work: Shevaun Wright

by Kimberli Meyer

Shevaun Wright is an artist and a lawyer. Her work delves into language and power, patriarchal and white supremacist tyranny, and concepts around the social contract. She earned her Masters of Law at the University of Melbourne and recently graduated from University of California, Los Angeles with a Master of Fine Arts. Her interdisciplinary fluency, Australian aboriginal heritage, and feminist perspective combine to yield a singular, thought-provoking body of work. Kimberli Meyer spoke with Wright, now based in Los Angeles, over Zoom in the summer of 2020 to discuss her artistic practice. The following is a lightly edited transcript of their conversation.

Kimberli Meyer: You’re working in this space between art and the law. How did you get there?

Shevaun Wright: In high school my first love was art. I used to spend my lunch times in the art room, and then I just pursued it as a hobby. I trained as a lawyer and earned a Masters of Law, practiced in Sydney for about six and a half years, and towards the end of that, studied art at a university in Sydney. At the time I was painting — for me, that’s what art was. And then I became exposed to more contemporary indigenous art that was highly political and engaged with legal issues. After I graduated, I started making art. It started initially with making fictional contracts about social situations and playing with the idea of the social contract.

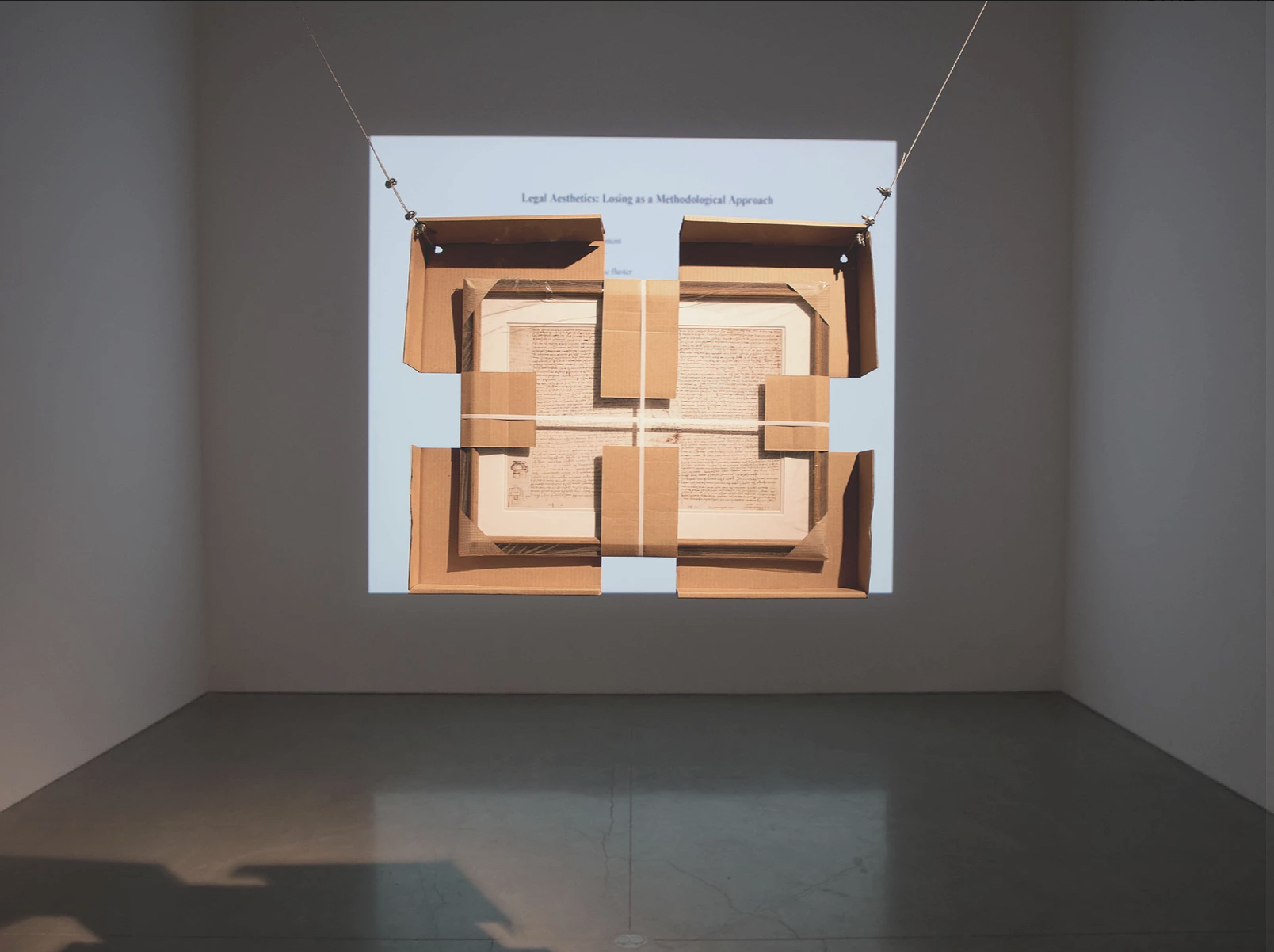

Then I went to New York and studied at the Art & Law Program, and I was fortunate enough to attend the inaugural Legal Medium conference at Yale. That’s where I was exposed to more artists and theorists working in this area. I returned to New York three months later, having resigned from my job in Sydney, to attend the Whitney Independent Study Program. That grounded me in a lot of political theory as well as the activist potential of art. I decided to specialize in growing this field of legalist aesthetics.

KM: Do you see your work intervening in both fields of art and law in an activist way?

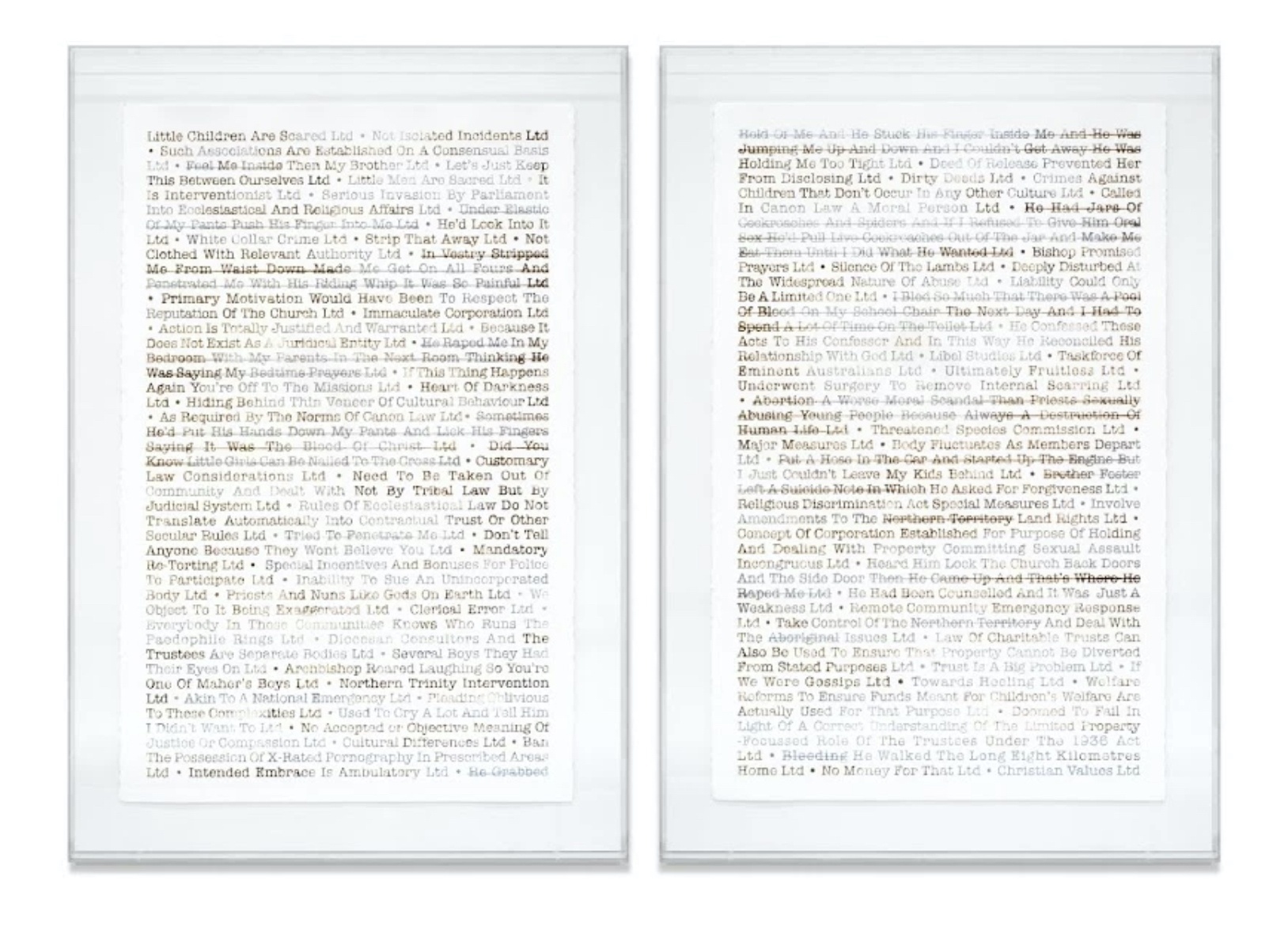

SW: I guess that is my goal. I made a work in 2015, Site-specific Artwork 2015 (Suggested Corporate Names – Catholic Church Child Abuse Compensation Entity), about a federal inquiry into the Catholic church in Australia and the issue of child sexual abuse. It was focused on the trust structure of the church. I presented that work in an artistic context, but it was shown in Parliament. I was able to meet with a minister at the time who then disseminated the work while they were voting on amendments to a law that limited the timeframe in which victims could come forward and sue the church.

That was a really cool moment for me because I had been working within the legal system for a number of years, but it wasn’t until I was able to occupy an artistic space that I could take a step back, look at the larger system of law, and be part of making change in that area. I’m definitely also interested in contributing to an art conversation at the same time. So, my work is a constant straddling act between the two.

KM: Was that a successful action, in relationship to the church and what was going on with the legislation?

SW: Yeah, they actually did pass that legislation and removed time limits for victims of sexual abuse. The artwork was acquired by Parliament as part of a prize it won, though I’m not sure if it’s on display. The work also pushed legal issues because it used testimony from victims of child sexual abuse. In an artistic context, that can be seen as reproducing child pornography, because they were explicit accounts. I had to get legal advice on the display of the work from a specialist. It was also a form of agitation, because these victims, for that reason, aren’t heard. So the work was pushing up against a lot of limitations.

KM: If something is taking the form of an artwork while maintaining a robust legal foundation, why is that potentially more productive than a conventional legal route? Do you have a theory about that yet?

SW: I think there are always limitations with art and what audiences you can reach. But I do think art creates a space for re-imagining. My practice normally is about languages confronting each other. So, here the legal institutional language is butting up against people who aren’t facilitated to be heard within that system. When you’re working within that system, you’re obeying all the rules and playing the game. In an artistic space, you can break some of those rules in order to really examine the gaps and who falls through them. Sexual assault survivors are a prime example of that, of not being heard within institutional systems. I think art offers a space in which you can bring together those conflicting dialogues.

Site-specific Artwork 2015 (Suggested Corporate Names – Catholic Church Child Abuse Compensation Entity), Shevaun Wright, 2015.

KM: It’s an expansion of the legal imaginary, a way to open up the very strict thinking that’s normal in legal processes, and to work on the law through the imagination of people who are tasked with making and interpreting laws.

SW: Yeah. I guess my work in graduate school was sometimes criticized for not offering answers, but my focus through my art was more on problematizing the law. Sometimes people come away from my work feeling really defeated that you can’t have any faith in the system. But I guess my main goal is to start conversations, because I do believe in gradually chipping away at something. Historically, a prime example of this is the activism of the feminist movement. They chipped away at the law and worked on it as a system, little by little.

KM: You could argue that art isn’t supposed to solve problems. It’s supposed to make problems, in certain ways.

SW Yeah. Some people say that it’s not about the answer, it’s about the question.

KM: What are some of the differences and similarities between the Australian and U.S. legal systems?

SW: Well, Australia lacks an acknowledgement of indigenous people in their constitution. So that’s a major issue of reform.

KM: So that’s a similarity.

SW: It’s a similarity in that there are some really deep wounds caused by Australian law that remain unaddressed. There have been protests against the Australian system that parallel the Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S. Interestingly, a recent BLM march in Sydney was ruled illegal the morning of the event by the Supreme Court of New South Wales, on the basis that it was a health hazard. Yet an estimated 30,000 people turned up, because we have a really serious problem with indigenous deaths in custody. In the 1990s, there were federal inquiries about it, and as of today not all of the recommendations of the Royal Commission have been put in place. We have such high numbers of Aboriginal people dying in custody, and a very high rate of incarceration among indigenous women. It’s the fastest growing prison population in the world, actually.

KM: Critical legal scholars here say that the U.S. system is essentially working as designed, that it’s fundamentally unjust going back all the way to the nation’s formation. I’m wondering how you see the connection between state violence, state power, and the law — how they work together or against each other, and how changes are made within these frameworks.

SW: That’s a massive question. I do think we really need to examine the deepest structures of the law, because the assertion that it’s actually working as designed, fundamentally, is true. And particularly, we need to examine the language of the law and ask who it’s written for and how it deals with bodies. A lot of feminist legal scholars I admire question the bodies that lie under all that really dry legislative language. Who does it actually protect? And again, my work has been criticized because it doesn’t offer a lot of solutions, but it does point to cracks in the law, and maybe hypocrisy and, essentially, glitches.

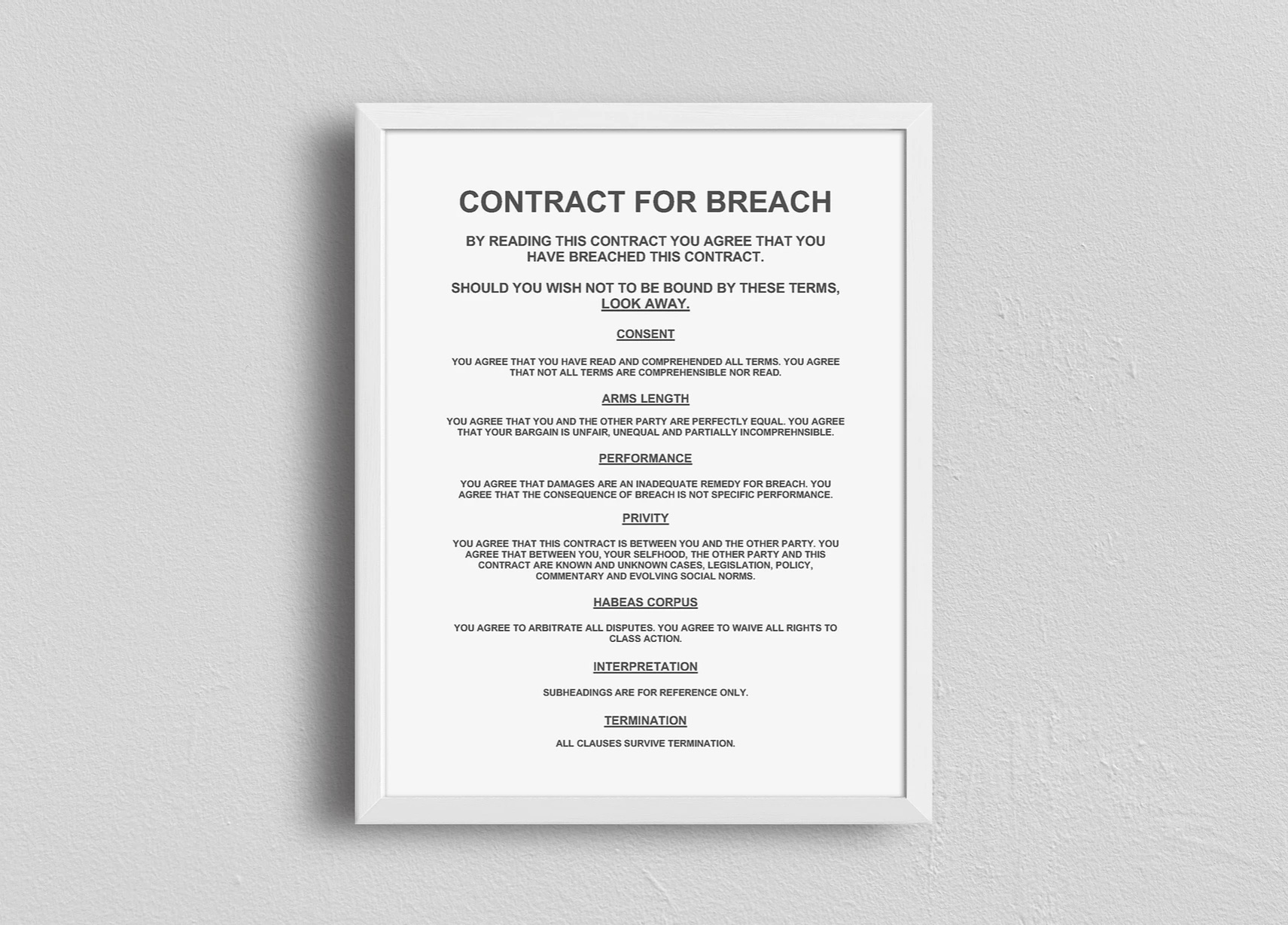

The law can’t maintain its own standards if it operates in this way. So, for example, my contractual work has focused on something that all commercial lawyers know, that a contract itself is based on fictions. We maintain a belief in social contracts as the only way of organizing society, as a rational and infallible system, but this system actually relies on fictions. One fiction is that the two parties on each side of a contract are perfectly equal, that in their negotiating power no one has been coerced into signing anything. We like to assume that each party is perfectly aware of every single term and what it means, and that’s just not true.

KM: Language is the medium of law and it’s also the medium of your work. In regard to these fictions you describe, I’m thinking of your piece Contract for Breach. It starts off with the warning: “By reading this contract you agree that you have breached this contract.” Under the “Consent” clause you say: “You agree that you have read and comprehended all terms. You agree that not all terms are comprehensible nor read.” To me that’s so typical of everyday life and most contracts people sign. That’s the “I agree” button when you click to load software or participate on a social media platform. There’s an absurdity that’s very banal. And it’s in a funny and very accessible way, but it’s shocking because it feels so true, from the quotidian level to the macro-structural level.

SW: To be honest with you, I don’t like to look at contracts for showing my art. I’m an emerging artist and the power disparity is extreme. People ask me what I think about artist contracts all the time, knowing my expertise. And I reply, “I didn’t read it.” I didn’t want to know. It seemed like a great opportunity.

KM: Contracts always seem so boring. But once you actually get into them, you realize that the material contained has so much meaning and that in art we’re talking about the symbolic realm, so we should pay a hell of a lot more attention to these things. But artists don’t want to. I totally get that. One of my ongoing questions as a cultural producer is how to make art contracts more reciprocal.

SW: It’s a microcosm for society. One of the contractual works I did involved rewriting the 1971 Artist’s Reserved Rights Agreement. I looked at that document and thought it was pretty hilarious, particularly all the bold assertions it was making about how it was going to change the art world. I wondered who was actually consulted in writing that agreement and what bodies it was protecting. So yeah, legal absurdity is a hobby of mine.

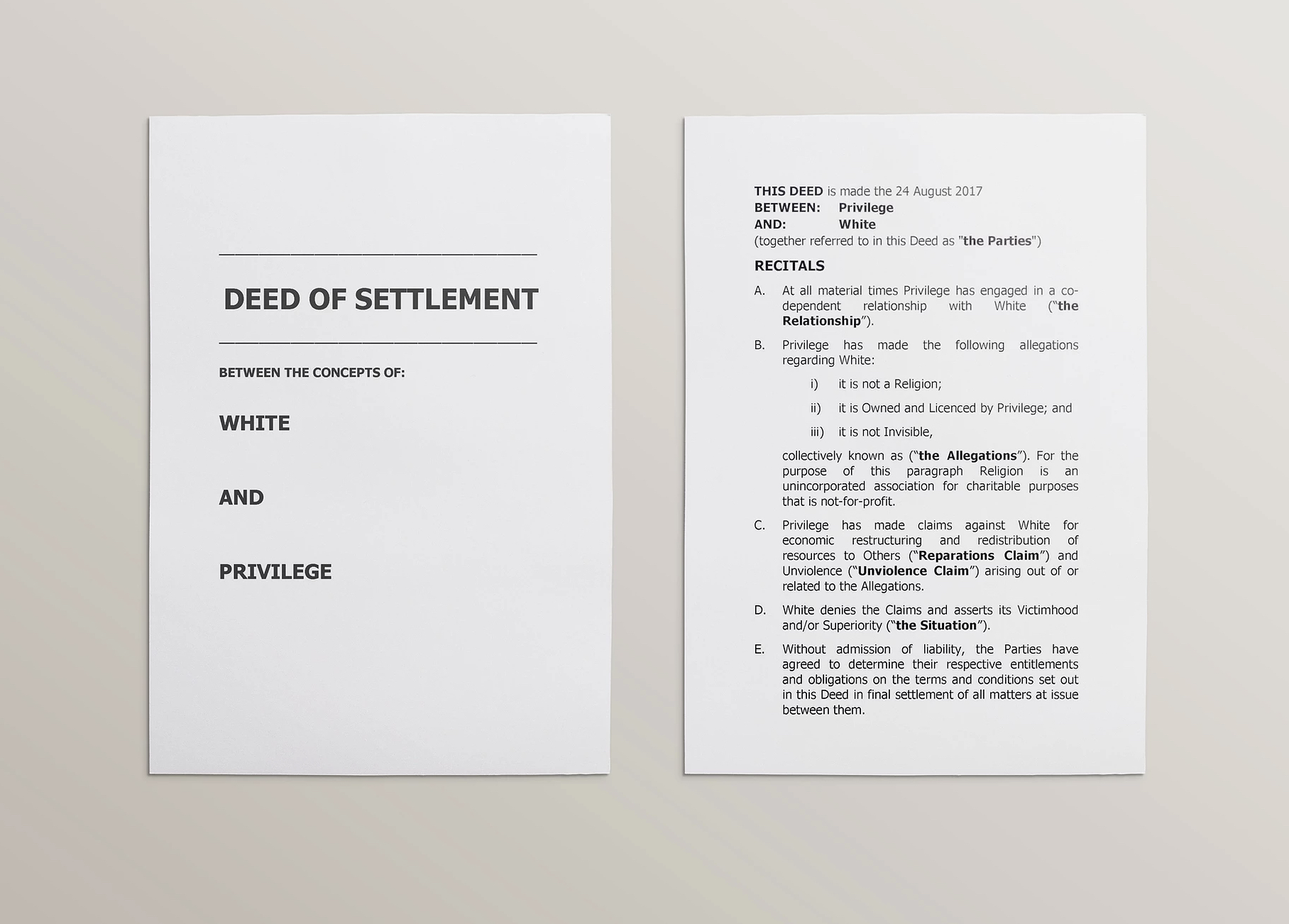

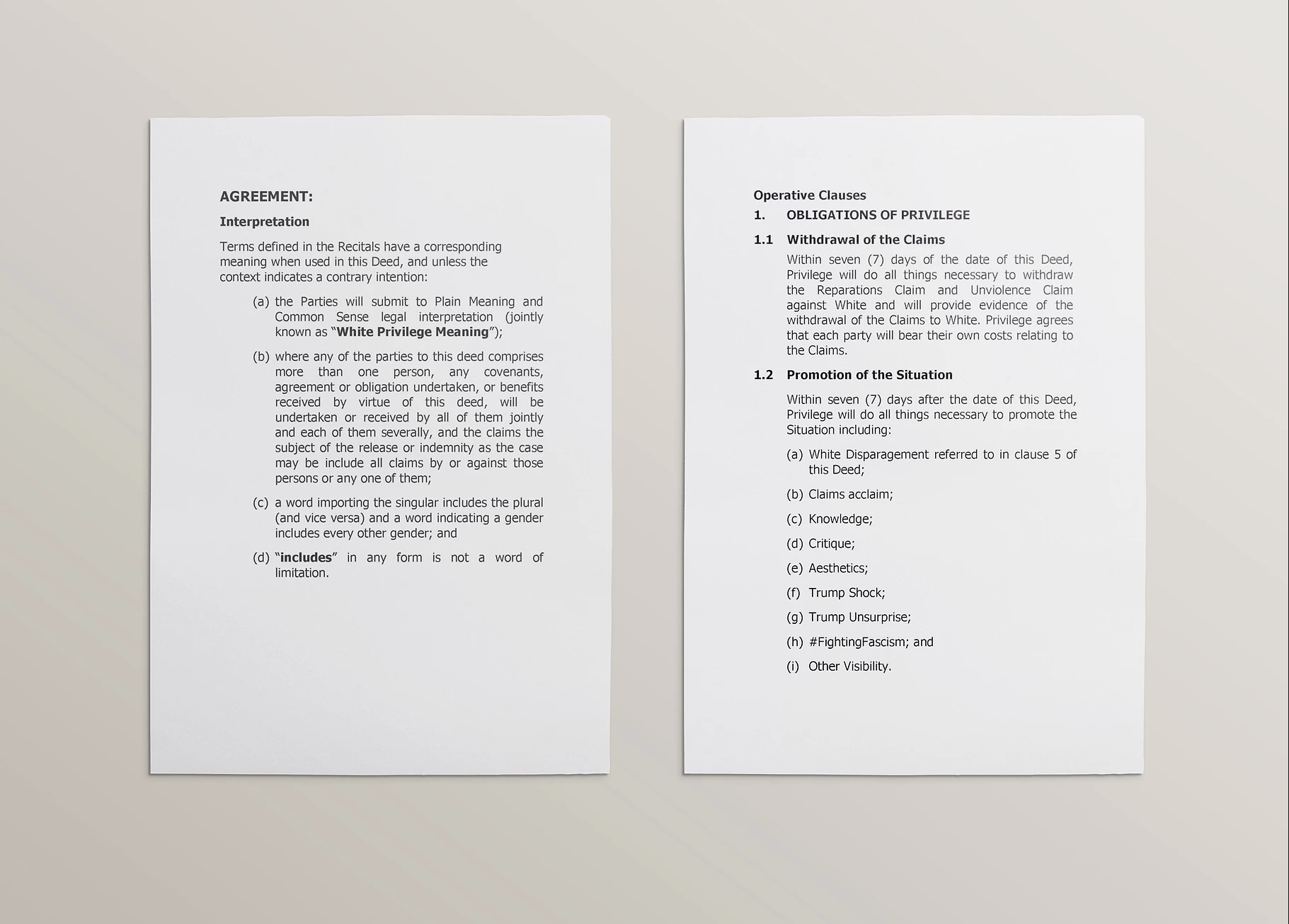

KM: Your piece White Privilege Deed of Agreement is an agreement between the concepts of “White” and “Privilege.” It’s devastating but funny, and accessible. It gets the lay reader to ask who is subject to the law and who benefits. As a white person, I certainly benefit from the law. It’s written in my favor. For most of us, the law is pretty unintelligible. There’s a gigantic industry around making sure we feel that we can’t understand it. We have to hire somebody to help us navigate it. So here again, you’re showing how language can be used to clarify, but just as often it can be used to obfuscate. Your work points to that contradiction and asks what’s serving what.

SW: White Privilege Deed of Agreement was inspired by the settlement of my friend’s rape litigation and civil claim. Her settlement documents included the deed of release, a very standard legal document that contains apologies without any admission of liability. It’s an incredible thing, a legal creature in which you can say sorry for something without admitting that you’ve done it. It’s fascinating to me. Nobody in law thinks about it because it’s such a standard release.

That seemed perfect for extending the idea of a fictional contract to a conceptual sphere rather than an interpersonal space. Within those documents, you have an agreement as to what the language of the document will be. It was a perfect opportunity to epitomize the fact that, like whiteness and privilege, they can’t get outside of their own discourse. They’ve already agreed to use that language.

The work I was talking about earlier in relation to the Catholic church coincided with a major case in Australia that found that the church couldn’t be held responsible for payment of these abuse victims because it held all of its money in a separate trust. Contemporaneous to this legal discourse was a cultural discourse in which the Prime Minister at the time was claiming that Aboriginal culture was full of pedophile rings. There was a sensationalized language particularly around Aboriginal men and “primitive” culture harboring predators. What was actually found was that there weren’t pedophile rings operating in Aboriginal communities. But these communities were sitting on very valuable mining land that the government was then able to obtain under compulsory leases, for less than market value, on the basis that they were protecting Aboriginal children from pedophile rings.

KM: Wow.

SW: Oh yeah, it was really big news in Australia. It was actually called “The Intervention” and the army brought their tanks into remote Aboriginal communities. Signs were erected that banned pornography. Children in these communities were, without the consent of their parents, tested for sexually transmitted diseases. It has been absolutely condemned by the UN.

What I was doing then was redirecting that language to illuminate how a very privileged institution, the Catholic church, was treated by the law. Of course, the Catholic church has now been found to have had extensive pedophile rings operating within it. In fact, the head of the church at the time, Archbishop Pell, magically disappeared to Rome and became the head of the Vatican bank. He was unavailable to give evidence in person when requested to appear by the federal inquiry. His doctor found that he had heart problems.

Eventually he was extradited and charged with pedophilia. He was convicted twice before the case went to our highest court in Australia, where it was overturned. So, this is how language operates. You have a very powerful institution versus a very oppressed minority. One gets labeled primitive and the other is protected by the law.

KM: Which brings me back to a previous point about the system essentially working as designed. There are other systems of justice in the world. There’s restorative justice, which has to start with a real apology as opposed to the apology that you just discussed. Is there any way to think about restorative justice systems in relationship to language that might create a different way of imagining things? Is that something that you’ve looked into at all or have any interest in?

SW: I guess the pop culture perception of a lawyer is that you fight — you engage in adversarial conflict. But how it actually happens is that you’re engaged in Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) processes. The best lawyers are looking for negotiated outcomes and I think there’s a lot of hope in the mediation process. So, on a very practical level, yes — mediation, ADR, restorative justice, and the value of an apology to a survivor of sexual assault is extremely important and something that lawyers actually can get in a way of by protecting certain interests and offering conditional apologies. That was definitely something that I witnessed when I was going through the process with my friend. There were things that she wanted that couldn’t be comprehended by the legal system, or couldn’t be facilitated.

A lot of my art does tend to be quite angry. I had a professor ask me in a studio critique if I could ever write a happy contract. I was like, “Oh, I’ll work on that.”

KM: Anger is required sometimes, right? A friend of mine once said, “Where there’s rage, there’s hope.” But there’s a strong sense of humor in your work as well, like when you point to the absurdism. I think that makes it more accessible. It sinks in deeper if I’m also allowed to laugh a little bit.

SW: That’s really good to hear because the humor is a strategy to take down walls that come up when you try and talk about difficult issues. When I normally come to making a work, I’m extremely angry and in shock that this is what the world is. But then, in order to speak about it with a broad range of people, I want to employ humor because I want them to laugh with me and come and digest the message of it.

KM: You talk about the notion of the social contract. It seems like that notion is present in our consciousness right now because of Kimberly Jones’s video that went viral around the Black Lives Matter protests. She talks about the relationship between looting, structural racism, and the economy. It’s a concise breakdown of how the social contract is broken in this country. Could you talk a bit about your thinking about the social contract?

SW: Actually, one of the first projects I worked on when I was thinking about making legal aesthetics my practice was The Rape Contract. It started in an effort to write out what my social contract would look like, and make feasible things that are invisible. I’m trying to use legal language as a medium to clarify how these invisible bargains are operating and who benefits from them. A lot of social contract theorists have made the critique that not all bodies were part of original agreements. They were subject to them, but they weren’t consenting and weren’t considered.

The first work I made about legal aesthetics, The (Foreign Investment) Scam, critiqued comments by the Prime Minister at the time, who said that Australia had benefited from foreign investment by the British. I thought, oh, that’s an interesting way of characterizing violent colonization and ethnic cleansing of Aboriginal people! And I wondered, what would that bargain look like? So, I wrote out that fictional document. Aboriginal people at the time weren’t even seen as people. They were classified as fauna and flora. It was essentially King George III contracting with nobody and getting everything for free. That’s a really good example of a social contract that was actually just highway robbery.

And again, with that work I used a lot of humor. I inserted real documents, like our constitution, that contain no acknowledgement of the original owners of Australia. Alongside this fictional bargain, I wrote a fictional email saying, “Congratulations, you’ve won a country.” I also included a little-known historical document of instructions issued to Captain Cook by King George III stating that if he finds lands in Australia that are occupied, he is not to take possession without the consent of the natives.

But Cook planted the British flag, having seen Aboriginal people everywhere, and declared that there was no one there. So, Australia is founded on a fundamental legal fallacy. He was exercising authority outside of his jurisdiction at the time. I haven’t made a project about that yet, but it’s interesting to look into the history of maritime law and what the legal implications would be. Australia has a long history of having problems with fantasy.

KM: That’s a white colonial settler problem, I think. And in the end, how does anybody justify such actions without concocting a fantasy? They probably couldn’t deal with that level of contradiction without telling themselves a story.

SW: Absolutely. And the fact that they were bringing freedom and civilization by then raping and annihilating all Aboriginal people is a huge irony.

KM: It’s a major disconnect. I keep thinking about law as culture and your work. In law, you have to make an argument based on a certain set of parameters. In many ways, your artistic arguments are more logical than the ones you find in the field of law. From an art perspective you can look at the law’s broader context. You can look at things less technically, less legalistically. You can get closer to the real philosophy, what it’s holding and what it’s oppressing. How do you see the potential in language, which can close something down but also, potentially, open things way up? And how does that relate to this larger imaginary and the kinds of fictions you’ve talked about?

SW: I really enjoy making language confront other language and showing the spaces between dialogues. I like Lyotard’s notion of the “differend.” The difference between a plaintiff and a victim is interesting to consider. The plaintiff can come before the law and be heard and make their case, but the victim doesn’t ever get heard because they can’t be facilitated by that system. My MFA thesis, Class Action, was an exercise in working within the system and throwing away any frustration and goals I had that didn’t fall within the legal framework.

What I found really satisfying was that when I came to display that work, everything that was lost could be foregrounded. The medium of art was compensating for what was lost within the legal process and all the frustrations I had. Because what I really wanted to do with that work, which was suing Eli Broad, was to talk about all of the domestic spaces that he profited from — and his company SunAmerica being acquired by AIG and the financial crisis. But when I was studying and researching it, all I could really find that would work within a legal framework was his attempted embezzlement of $10 million from the Hammer Museum.

So, I had to latch onto that fact. And construct an argument within that to make it work. Again, I do think that art offers a complimentary discourse that can question the things that don’t fall within another system of language.

KM: Class Action is intervening in the system itself and is activist in that sense. Even if that particular instance wasn’t your primary interest, it acts upon a larger system of injustice in the nonprofit sector, and art world shenanigans, of which there are many. By displaying all of these documents in an art setting, you’re able to tell the full story. In this case art can physicalize what law cannot. Yet nothing is taken away from the intervention itself. This having it both ways seems crucial.

SW: I’m just trying to remind people and make them aware that there’s actually so much lost within that process. There were humorous parts to it — like, you can’t make up his biography, The Art of Being Unreasonable, with him on the cover standing next to a Jeff Koons.

KM: What’s the status of the suit?

SW: Eli Broad was served personally and never responded. But that’s okay, he’s a billionaire. What I was most surprised about was that I sent two letters to the president of the University of California, where I completed my MFA work, asking for a response about his name being removed from UCLA’s art center building. I never received a reply. There’s actually a university naming policy that I referenced that contemplates loss of public trust and the fact that the general counsel needs to approach the state attorney general about the appropriateness of his name remaining on the building.

So, the next steps will be focused on agitating in relation to that. I do think that as a symbolic act it’s important to remove his name. That is my goal, ultimately. And I think that with all the hot water public universities have been in recently because of money buying positions in schools, we should be really focused on the role of philanthropy in these public institutions. All this new venture philanthropy is a neoliberal feature. What we used to call old-fashioned corruption is now very efficient philanthropy.

KM: Right. It’s got a new brand.

SW: My suit is not an unreasonable claim. Broad’s actions are well-documented. He’s worth $7.6 billion so it probably doesn’t seem like a lot to him, but misappropriating $10 million from the Hammer Museum — that’s a lot of money. It’s not something that should be overlooked.

KM: As you point out, the symbolic value of these donors having their names on these publicly owned buildings is already huge. And the symbolic value of having to take it down would be even bigger.

SW: Exactly. You also have undergraduate and graduate students operating under this brand. There have been psychological studies on brand affection and what that generates within people, like longing and loyalty. It has a very affective power. And so, yeah, it would be a powerful symbolic act, particularly in Los Angeles, a city that’s very much branded by Broad.