Artists at Work: Wu Tsang

by Carol Cheh

Wu Tsang and boychild during the production of A day in the life of bliss, 2013. Photo: Jesus Torres Torres.

Born in Massachusetts in 1982, Wu Tsang graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and was involved with the local underground scenes in that city before moving to Los Angeles in 2005. Two years later, he moved to the MacArthur Park neighborhood just west of downtown and lived near the Silver Platter, a historic Latino bar for the LGBT community. Inspired by the thriving scene there, Tsang and his friends (Ashland Mines [aka Total Freedom] and NGUZUNGUZU [Daniel Pineda and Asma Maroof]) organized a weekly party at the bar featuring dancing and performances and called it Wildness. The intersection of subcultures that ensued became the subject of a fanciful documentary film of the same name, released in 2012, which is now his best-known work.

Tsang’s relatively young practice, which flows freely through performance, film, photography, and installation, is grounded by a cluster of recurring themes: the fluidity of gender and identity, social gathering as a form of insurgency, the fraught act of translation, how subcultures form and thrive, and the tensions that occur between filmic/theatrical conventions and a critical art practice. The Wildness documentary, which continues to get extensive play through film festivals and community screenings, is notable for its matter-of-fact depiction of conflict within a community and its resistance to linear resolutions.

Tsang received an MFA from UCLA in 2010 and was featured in several high-profile group exhibitions in 2012, including the Whitney Biennial and the New Museum Triennial. This year, he is one of 35 artists or artist collectives chosen for the Hammer Museum’s “Made in L.A.” biennial survey exhibition. I sat down with Tsang in his modest, utilitarian Koreatown studio for an in-depth discussion of his practice and the work he is premiering.

Still from A day in the life of bliss, 2014. Two-channel HD video, color, sound. 20 min. Courtesy Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin, and Clifton Benevento Gallery, Los Angeles.

Carol Cheh: So tell me about the project you are doing for “Made in L.A.”

Wu Tsang: It’s a two-channel, 20-minute film called A Day in the Life of Bliss—part of a multifaceted project that I’m making in collaboration with a performer called boychild. There are a couple of layers to it, but the main layer is a science fiction story set in the near future that I conceived and then co-wrote with Alexandro Segade. I was inspired by a couple of films, mainly Charles Atlas’s Hail the New Puritan [1987] starring [Scottish dancer and choreographer] Michael Clark. It features Clark and his friends dancing a sort of punk rock ballet to music by The Fall, and Leigh Bowery did all the costumes. Charles calls it a docufantasy portrait of a subculture—in this case, the post-punk British club scene. One of the things I learned from Charles was that he was inspired by the Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night and wanted to make his own version of it for his underground friends in London. Looking at the legacy of both of those films, I decided that the “day in the life of a performer” film format was an interesting way for me to pick up some of the threads I had started with Wildness.

CC: Which threads are you thinking of?

WT: I’m interested in thinking about counterculture and underground culture as spaces of resistance, where culture producing and partying bring bodies together—how that informal space can be really important for social movements. I wanted to make a film that addressed how our notions of the underground have really shifted with the Internet. Even since I made Wildness, which was primarily filmed in 2007 and 2008, a lot of shifts have happened in terms of how we use social media. Wildness happened in a MySpace moment, before Instagram and Facebook even. Those virtual worlds weren’t as integrated with our lives; the primary community space was still a physical one. Whereas I would argue that now our sense of community is really fluid with the virtual—physical space is almost secondary to the role that virtual space plays in our daily lives.

Still from A day in the life of bliss, 2014. Two-channel HD video, color, sound. 20 min. Courtesy Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin, and Clifton Benevento Gallery, Los Angeles.

CC: Tell us a little more. Who is Bliss and what is her world like?

WT: The world that I imagined is this world in which our social media avatars develop a sort of hive-mind consciousness and start operating on their own without us. Bliss is a young, up-and-coming celebrity performer. In this world, celebrities are collaborators with these hive-minded avatar beings—the Looks—because they generate the most photos, the most looking. Bliss came up doing a kind of underground drag performance, and she’s really talented at it. She has a mutant superpower that she doesn’t yet know about but discovers in the course of her day.

There are nuances, but it’s also a classic superhero origin story about a character that has some innate ability to see the world differently, to act differently than other people, but she has to grow into that power. Bliss has to overcome ways that her lifestyle is corrupting her and will eventually kill her in order to challenge the system. The film is about a day that pushes her to the point where she has to make a choice to fight back. The implication is that there are other people like her and who could potentially create a movement.

I wanted to use a more conventional storyline, because the way I’m staging it is unconventional. For example, the film also plays as performance art or dance film. The character Bliss is a performer, so each scene is paired with a dance that’s kind of interpretive of the story. I worked very collaboratively with boychild on filming these performances, because they really are her performances. It is a way of weaving documentary into the film. In fact, once I knew that I was working with boychild on this project, I adapted a lot of the character details and plot to fit with her performance style.

CC: It does sound like a classic hero’s journey, which is interesting because I know that you were using and subverting that archetype in Wildness, too.

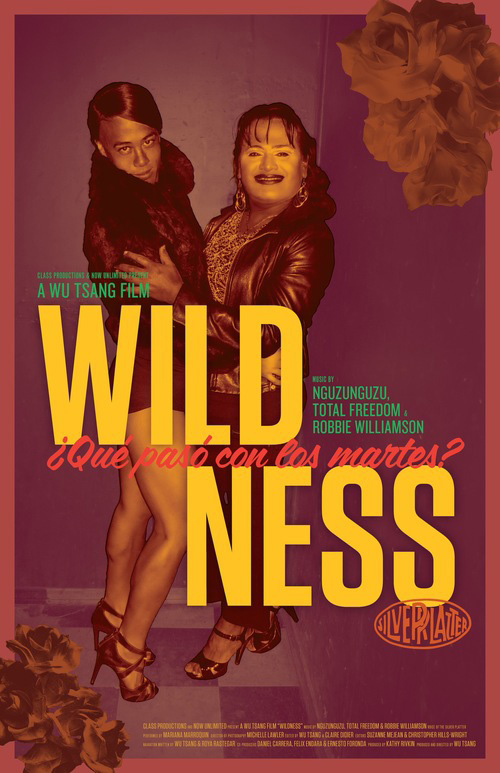

Movie Poster for Wu Tsang, Wildness, 2012. HD video, color, sound. 74 min. Courtesy of the artist.

WT: Well, I was and I wasn’t. With Wildness, the main characters are the bar and myself, and the film can be considered a pretty conventional coming-of-age story. It’s about my character being this younger, more naive version of me that comes to the bar with a need, and the bar is this elder parent figure who helps me and is tough with me when it needs to be. It’s about my transformation, basically, and the realizations that I have. All the questions that are raised by the film are questions that my character has to struggle with in a more direct, personal way.

I would say that Wildness is not a conventional documentary because it also has this magical realist layer to it. Throughout every film that I’ve made, I’m really invested in hybrids—like documentary-fiction, reality-fantasy hybrids—because I think that the arbitrary line that designates one as truth and one as fiction is completely wrong. I’ve noticed a general trend in documentary: that the most innovative films are increasingly hybrids, which play with staging and the subjects’ participation. Filmmakers seem increasingly free to dispense with a lot of those formalities around—

CC: Claims of objectivity and truth?

WT: Yeah, or there are certain rules that are like codes of honor with documentaries. At one point, I was really interested in breaking every one of them if I could! Now I don’t even feel that constrained, as though I have to react against a structure.

CC: This seems to be a recurring dynamic in your major works—using a more conventional narrative structure but then mixing it with a lot of elements that are not as cut and dry or resolved. It makes for an interesting mix where you have popular appeal but then you also have a questioning of standard formats or ways of thinking.

WT: As a visual artist, I feel equally in dialogue with cinema and storytelling. There are very different ways of working, as an experimental video artist versus being a filmmaker, and I try to draw from my training and experience working in both realms. One thing I learned from making Wildness is the basic concept of visual storytelling—that if you want to say something, it helps to communicate it visually, not just in words, but also in visuals and music, etc. Film enables this kind of three-dimensional storytelling to convey meaning beyond language.

Coming from a more conceptual background in visual art, I was trained to work with systems and processes, where film had more indexical relationship to the idea. For example, I might set up a scene based on a question or scenario, and then film it—intentionally not wanting to construct the image. I used to consider conventional film narrative to be manipulative because it was so counter to my methodology. But with Wildness, I had to serve a story as much as a conceptual framework. In documentary, how the footage is produced and the process behind it are way less important than how it ultimately gets used and serves the story.

Still from Mishima in Mexico, 2012. HD video. 14 min. Courtesy of the artists.

CC: I’m reminded of Mishima in Mexico, because I think of that piece as a very conceptual piece—in terms of you and Alexandro clearly having a concept that you then methodically executed—but then it’s embellished with these incredibly theatrical features, like the lighting and the stage design.

WT: In Mishima, there’s a lot of heightened drama, but at every given moment it’s also very apparent that we are just two artists in a hotel room, playing with the fantasy of what we’re doing. But we’re also not pretending. Alex and I were not interested in fully suspending disbelief; we’re interested in how daily life can lead to these play activities that can transform your reality but also keep you in the reality at the same time.

Some of these intentions carry over into A Day in the Life of Bliss, which Alex is also a co-writer on. He’s a collaborator that I continue to work with, along with my editor, Augie Robles. We referenced at a lot of amateur sci-fi, because there’s something great about a film like Born in Flames [directed by Lizzie Borden, 1983], where they set up this grandiose premise at the beginning of the film: The U.S. government has been taken over by the socialist democrats and now women are in charge or whatever. They say that but then it’s just, like, New York in 1983. I’m interested in how we evoke these utopian fantasies but then it’s also just like life, because it’s about how we can do that now if we want to. We can just have a different idea of the way things should be; it doesn’t take a million dollars to imagine it.

CC: Since A Day in the Life of Bliss is the first chapter of a planned epic, will it feel like a teaser or a cliffhanger? What can we expect when we go in to see it?

WT: The work at the Hammer is an installation. I love to work in installation because it gives me the opportunity to explore simultaneity with narrative. The idea is that viewers can walk in at any time, and I don’t have control over when or where they sit down, or how long they stay. That also creates different possibilities for viewing, so no two people will have the same experience of viewing it. I created a special viewing environment that is like a box with mirrors and screens. You have to be inside of it in order to see, but in seeing you also always see reflections and reversals of what’s happening.

I got really interested in mirrors when researching different analogies that people are making to social media. One of the familiar discussions is that social media is generating a lot of narcissism. I read one interesting study of search engines, which said that instead of expanding our horizons as these algorithms originally intended to, they are functioning more like mirrors—the more we look out, the more we just see ourselves.

Wu Tsang, Green Room, 2012. Two channel video, mixed media. Installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, 2012. Courtesy Clifton Benevento Gallery, Los Angeles.

CC: Do you see this installation as being particularly relevant to the Hammer or to Los Angeles in some way?

WT: This story is not specifically about LA, but it’s definitely conceived through the prism of being based here. I’ve lived in LA for ten years now, and it’s always been such a generative, creative space for me. It’s the most amazing place to live and work as an artist, I think. There’s also something about being here that just generally gets my mind and my imagination going. Like, visually around me—the light, everything, the social life. Also, most of my collaborators are based here, like my editor and producer. I’ve learned so much about filmmaking from being a part of the community here.

CC: It’s funny how this film was inspired by Hail the New Puritan, which was itself inspired by A Hard Day’s Night. It’s like generations of inspiration building on each other, and they all kind of have similar concerns, in some ways.

WT: As a performer myself, I often think of my art practice as a way to create platforms for performance and a frame through which to understand performance. A film can function as a kind of stage for performance. I wanted this film to be like a window to a world, similar to the way that Atlas collaborates with a lot of people in his film. Basically, it’s meant to be another snapshot of a moment in time, showing the connections of different artists that work together across disciplines like music and art and nightlife.

CC: These ideas seem very central to your practice—collaboration and creating safe spaces for experimentation. With this new film, do you see cyberspace as a potential safe space or platform for creation?

WT: I don’t really see cyberspace as its own “space” because it’s so integrated with daily life. But I certainly question it. There are studies about what the Internet is doing to our brains, how it’s actually changing our neural pathways because it’s altering the way we read and store knowledge. I don’t pass judgment on it because it would be pointless to reject what’s already happening, but I do have a lot of questions about where we can locate our sense of political agency within our shortened attention spans. I’m always interested in the conditions of catalytic moments, in trying to understand circumstances that necessitate people taking a stand or articulating a demand. I’m interested in what would be an emotional catalyst for someone now, for a young person to feel motivated enough by information that they would actually want to do something about it, because I think it’s hard.

Wu Tsang and boychild, performance at Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin, May 2014.

CC: You said earlier that you were collaborating with boychild—does this mean that she’s helping to develop the storyline, too?

WT: There are pieces that are distinctly hers, which are the performances that her character does in the film, and with those I really see my role as creating a context and a frame. Live performance usually doesn’t translate directly into film, so part of my aim is simply to create a portrait of a performance artist. For example, what does rehearsal look like? I’m interested in daily artistic process—to demystify it. A big part of my collaboration with boychild has been trying to understand her process and interpreting that for the film and story I want to tell.

CC: One of the most exciting parts of Wildness for me was seeing those little snippets of video capturing performances by people such as Dynasty Handbag and Flawless Sabrina. You must have a huge database of footage from those years.

WT: I’m actually working on our digital release, finally. It’s taken a while because we had to get the funds to clear it for digital. But I’d really like to have some sort of DVD extra that’s an extended version of the performances, because there’s just so much amazing performance. It’s a whole archive—hours and hours and hours of it.

CC: I’m curious about who or what you consider your influences to be.

WT: So many people. Mary Kelly was my mentor at UCLA. She was the person who first gave me this understanding about what a “project” is, which for an interdisciplinary or conceptual artist is about having a set of questions or a point of view through which to look at the world. The work can then take many forms—it’s not necessarily medium-specific. I also studied with Yvonne Rainer as a grad student. Taking her Materials for Performance workshop was really transformative for me. There aren’t too many outlets for learning a discipline or a practice around being a performance artist, because it’s not as institutionalized as dance or classical music, so I learned a lot from Yvonne and Mary. I also studied with Gregg Bordowitz. He was a mentor in my undergrad years and has continued to be a very good friend. Thinking about artist-activist-filmmaker practices, he is someone that I’ve been in dialogue with for years.

I look up to certain artist filmmakers, like Steve McQueen. He is popping off in a major way right now, and it’s been great to follow his career. I like the way he talks about cinema and video installation in terms of physicality. More and more, the way that we consume media is on these personal screens—like a laptop or phone—where we have these very small, private relationships to images and stories. Cinema and installation offer the possibility of having a physical impact on a viewer; you can actually affect people with scale and with sound physically. It creates a very different full-body experience. Technology is taking us out of our bodies and more into our heads, and I think that’s a reason why cinema and installation will always be important. You just can’t replicate what that does to you on a smaller scale.

CC: I’ve read interviews where you say that performance is the baseline that you always return to. Besides Yvonne Rainer, were there any other influences on the development of your performance practice?

WT: Maybe I’ve even learned the most from participating in nightlife. My roots are in drag performance. I also grew up in a queer-performance-art family: I trained opera with Juliana Snapper, Zackary Drucker is my sister, Ron Athey is one of my dads, Vaginal Davis, Flawless Sabrina, Nao Bustamante. The first performance I ever did was opening for Nao at an LTTR event in New York.

CC: I lean toward the school of thought that performance can’t be taught anyway.

WT: For me performance is like research; lived experience is fundamental. I have to do these things to understand or have any critical analysis. I’ve never been someone who’s going to stay behind the camera and observe. I don’t perform onstage that often, but when I do it’s often part of a process—it’s a way of thinking through things.

Wildness family portrait, 2012. Courtesy of Class Productions & Now Unlimited.

CC: Let’s go back to the Wildness project for a moment. As the film has gotten more attention, has it brought more attention to the bar [the Silver Platter]?

WT: I’ve been going to Silver Platter periodically, and it hasn’t changed so much, or at least not in the way I think you’re asking. We were lucky with how Wildness transitioned out of the bar; we managed to sort of disentangle without having a huge affect on the clientele who still go there, and life goes on. There are some changes, obviously, like Morales isn’t directing the drag show anymore. Nicole just had her last night working the door recently, which was really sad for me. I couldn’t believe it. I was like, “You can’t stop!” But she was like, “I’m done. I’m moving on.” I try to have perspective about change that is not limited by my personal experiences or the film. Life continues at the Silver Platter.

The thing that humbled me about that whole experience with Wildness was, like, these details and these changes meant so much to me at the time and I felt so responsible. Like, at any given moment, if something was slightly different, I was like, “Is this because of us? Is this our fault?” But actually the bar has been there for over 50 years, you know what I mean? It’s definitely changed a lot more than we changed it. Even imagining that we could have that scale of an effect was presumptuous, albeit well intentioned and trying to be aware of privilege. That was a big lesson I learned: to acknowledge the limit of what one can control and how to be ethical within the framework of power and having actual relationships with people. In a real relationship with someone, you don’t pity them or feel protective of them; that’s just paternalistic and colonialist and fucked up. It was a really delicate tightrope.

As for the film itself, in 2013, I was traveling quite a bit and I did a lot of screenings in different places, mostly in Europe. That was really interesting because a lot of times there would be self-organized parties that people would throw, that were sort of inspired by what they imagined Wildness to be, because they hadn’t even seen the movie yet. And that was really, really fun. I felt like the film succeeded in achieving something in that domain, where I always wanted people to take it up and feel like it was theirs.