Castaways of a New Cosmic Catastrophe

by Silvia Maglioni and Graeme Thomson

Unless otherwise noted, all images are stills from Graeme Thomson and Silvia Maglioni, In Search of UIQ (2013). Courtesy of the artists.

In 2012, Paris-based artists and filmmakers Silvia Maglioni and Graeme Thomson visited Los Angeles to research an unpublished science fiction film script written in the early 1980s by French philosopher Félix Guattari. According to the artists, the script for Un amour d’UIQ “offers a blueprint for a subversive ’popular’ cinema through an imagined hyper-intelligent infra-cellular life substance—“UIQ” (Universe Infra-quark)—capable of controlling global communications networks and plugging into the “desiring machines” of a community of squatters” To mark the release of their film essay, In Search of UIQ (2013), which will have its world premiere on February 28 at REDCAT, we asked the artists to contribute an essay about the culmination of this multiform research project and reflect on their visit to Los Angeles last year.

Nothing can come of nothing. The infinitely small is not the same thing as nothing, though it may be close. I seriously begin to doubt whether nothing exists. The Planck length, I discover, is the smallest calculable unit, though it apparently lies many million times beyond the scope of what our current instruments can measure. It is reassuring to know that something does.

If I try to picture nothing in my mind, it will usually be either all white or pitch black, depending on the mood, though I don’t know where this idea could have come from. I’ve been thinking a lot about things that don’t exist but are not nothing, or are nothing only in and of themselves, when no one is thinking about them.

Now I know. The white is like the empty screen before the lights go down, the black the moment just before the credits roll when the picture cuts out. But the film we are talking about does not actually exist, so the before and after are not black and white in the usual sense. Let’s say the white of the before merges with the black of the after, giving a grey like the fog now drifting down off the Hollywood hills or a mental block, or the way you might think of limbo, were you so inclined.

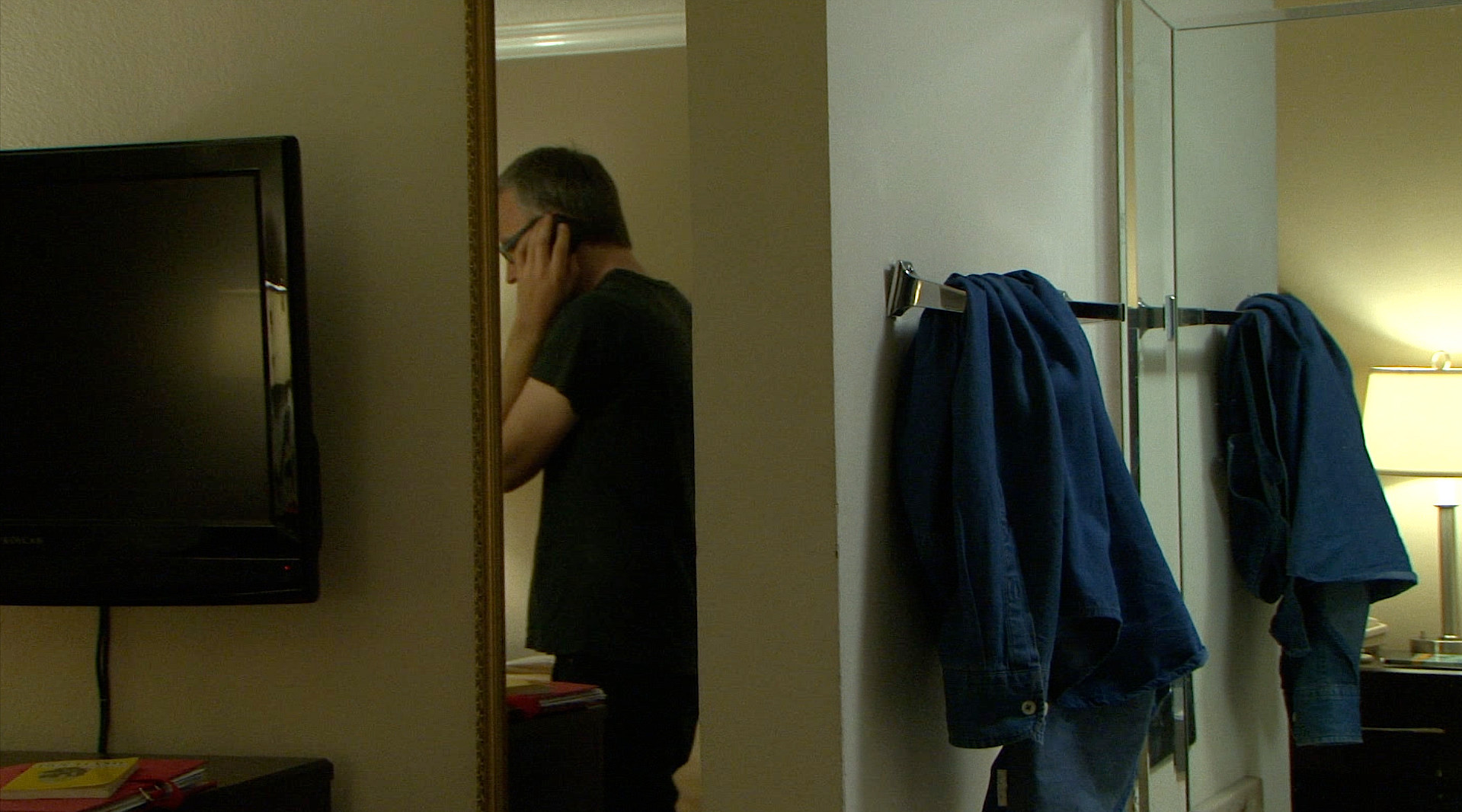

That’s the way it’s been for several days now, since we arrived. It’s kind of beautiful. You never see L.A. like this in the movies. A washed-out beige that slows all movement to a dazed and listless crawl. But here we are in Venice, a place that seems to have drifted off beyond the whims of time. You get the feeling that nothing of great concern will ever touch this place. That it would be, finally, oblivious to the arrival of a disaster so many times rehearsed. Morning rises in a dull temple throb of overcast. A red tractor draws wide circles in the sand as two Rollerbladers in mirrored shades skim past the clutch of homeless guys parked on the benches outside our hotel, the same we must have seen twelve years ago in more or less exactly the same spot. A desultory blues melismata lifts briefly from the muffled scree of beats, radio voices, distant sirens. It’s easy to see why the cult of UFOs is so strong here. Desertshore trance, parlor room cartomancy. Somewhere amid the stream of cash and credit card readings there is a certain readiness, the readiness of the exhausted, calmly awaiting an unlikely visitation. Castaways of a new cosmic catastrophe. This was the phrase Félix Guattari used in his sci-fi screenplay, Un amour d’UIQ, to describe the community of squatters who make contact with what he called “the Infra-quark Universe.” I forgot to mention it when I spoke on the phone to Michael. It was thirty seconds into the conversation and I was already on first name terms with Michael Phillips, the producer of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), to whom Guattari sent the first draft of his screenplay in 1982. But then I remembered it was only in 1986 that the phrase appeared in a note accompanying the third and final version of UIQ, submitted to the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’image animée [CNC] where it’s clear that Guattari wasn’t on first name terms with anyone. Anyway, it turned out, not surprisingly, that Michael didn’t remember the script, didn’t know who Guattari was, and yet his producer’s instincts remained somewhat intrigued by the notion of an Infra-quark Universe. And so I found myself pitching the film back to him, a strange re-enactment of something that never occurred.

Castaways of a new cosmic catastrophe. This was the phrase Félix Guattari used in his sci-fi screenplay, Un amour d’UIQ, to describe the community of squatters who make contact with what he called “the Infra-quark Universe.” I forgot to mention it when I spoke on the phone to Michael. It was thirty seconds into the conversation and I was already on first name terms with Michael Phillips, the producer of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), to whom Guattari sent the first draft of his screenplay in 1982. But then I remembered it was only in 1986 that the phrase appeared in a note accompanying the third and final version of UIQ, submitted to the Centre National du Cinéma et de l’image animée [CNC] where it’s clear that Guattari wasn’t on first name terms with anyone. Anyway, it turned out, not surprisingly, that Michael didn’t remember the script, didn’t know who Guattari was, and yet his producer’s instincts remained somewhat intrigued by the notion of an Infra-quark Universe. And so I found myself pitching the film back to him, a strange re-enactment of something that never occurred.

“So what is it now, is it a script that I can read?”

This story is pure science fiction. It’s the story of UIQ, the Infra-quark Universe; a dweller, I now see, of a Calabi-Yau dimensional manifold, one that knows no individuation, no gender, no distinction between self and other, without fixed limits in space or time. Axel, a brilliant young biologist, discovers a membrane permitting contact with this Infra-quark universe in a mutant strain of phytoplankton and then has to go on the run because the signals from the bacterium play havoc with communications networks. For, once contact has been made, UIQ is already potentially everywhere and everywhen, though invisible; a disturbance in the air that begins (if we can still use that word) to derail the physical laws of the known world. Axel hides out in a squat in Germany, recruiting its broken denizens to help him stabilize contact with UIQ via a DIY interface cobbled together from repurposed junk technology. UIQ begins to converse with the inhabitants, establishing more intensive relations with three in particular: Manou, a precociously intelligent little girl seemingly without parents; Eric, a schizophrenic who has a strangely intimate rapport with a washing machine; and Janice, a young punkish student and part-time DJ.

It is Janice who takes it upon herself to educate UIQ about the affairs of humanity, the nature of individuation and the distinctions between self and other, male and female, that—despite its vast intelligence—continue to perplex and fascinate our bacterial hero. And so UIQ attempts to individuate itself for her, to be “someone” for Janice, to conjure up a face and a voice. It finds that there are “others,” notably Axel, vying for her attention, and so it discovers, too, the meaning of jealousy and the desire to possess. UIQ in love? In the meantime, this face, a blurred enigmatic triangle of three black holes, begins to show its face everywhere: as an ineradicable stain of negative space on TV screens; in stirrings of pond water; in a flight of pigeons or a panicking crowd.

As I hurriedly try to convey to Michael the basic elements of the story over the phone, I’m at the same time imagining recounting this in a hypnotic flow of perfectly paced storytelling that will put all other concerns on hold—a pitch as black as the night of the world from which this new universe will be born. But is it a fantasy, or rather a parallel dimension where our conversation takes place in another timeframe? Storyteller’s time. Given time. All the time in the world. The time of UIQ.

UIQ is in love with Janice, but because it lacks bodily limits, its suffering is infinite. So it needs a body and, being a million times smarter than the smartest human or god, it manages to fashion one for itself, fully formed, without need of a test-tube or virgin’s womb. But the body, being a body and wondering what a body can do, rebels against its controller. UIQ, lacking the body it has made, can only float somehow holographically there, here, wherever, and watch, through those black holes of the face it has made, as the rebel body tries to take possession of Janice. The fog is slowly lifting from the Ventura freeway. A steady procession of sedans and SUVs keep their distance as they blithely slip between lanes, heading towards downtown. GPS guided drones of purpose and intent, going through the motions of moving. Did Guattari ever visit Los Angeles? Somewhat narcotized by all this driving, we try to imagine the scene:

The fog is slowly lifting from the Ventura freeway. A steady procession of sedans and SUVs keep their distance as they blithely slip between lanes, heading towards downtown. GPS guided drones of purpose and intent, going through the motions of moving. Did Guattari ever visit Los Angeles? Somewhat narcotized by all this driving, we try to imagine the scene:

Félix in Hollywood

– He’s come to see if he can interest producers in the UIQ script, though he speaks virtually no English. He spends a lot of time driving on the freeways, racking up speeding tickets, or in his hotel zapping through the cable channels and smoking in cafes because it’s still legal to do so in 1982.

– How many would there be then?

– What?

– Channels.

– Not a lot though certainly more than in France. Anyway, as the weeks pass he starts hanging out in Topanga at the French cafe, where he’s routinely assailed by terse greybeards clutching voluminous theses on the Rosicrucian MKULTRA Krishna UFO acid conspiracy. He rents a trailer to work on a second draft. But at the studios, nobody is buying this Infra-quark nonsense. Hollywood doesn’t do ‘the invisible’. Maybe the problem is in the presentation.

– You mean the part when he says, “I want to explore the cinema’s capacities as an instrument for producing subjectivities and the relation between their individualized and machinic components?”

– Pretty much.

– So what does he do?

– To make ends meet, with the help of friends, he sets up a schizoanalysis practice. The buzz gets around and eventually it becomes the go-to therapy option for stressed-out A-listers, edging shrinks and scientologists out of business. Soon actors, directors, producers, scriptwriters, editors, studio executives, casting agents, are all lining up for schizoanalytical treatment. It’s like another La Borde, for a different tax-bracket of psychosis.

– Does he get a show on the rehab channel? Detox from capitalism?

– You forget video is still in its infancy. Reality doesn’t exist yet, nevermind its spawn. The only cameras are the ones that the patients use themselves in workshops. Collective delirium is encouraged as an incentive to creative thinking. Roles are continually being swapped around as clients learn to shut off the money block that is clogging up the desiring machines. Back at the studios, marketing experts and their spreadsheets are laughed off the lot. “Sorry, I don’t have time for you right now. I’m working on my plane of consistency.”

– Unshackled from target demographics, movies become more interesting.

– Audiences start dreaming differently.

Amid this confusion, the laboratory is discovered, the squat raided and burnt to the ground. Janice escapes. Government scientists seize UIQ and try to make it talk. Instead, the inconsolable Infra-quark Universe, torn from its beloved Janice, decides to wreak a terrible revenge, recoding the DNA of the human population and transforming people into half-amphibian mutants who slop newly acquired tentacles and fins across their clunky computer keyboards, intermittently diving into a fish tank or toilet bowl for relief. Following a long silence, UIQ expresses its one desire, to be reunited with Janice. She, sensing the gravity of the situation, comes out of hiding and reluctantly agrees to have the phytoplankton containing UIQ inserted into her brain. Merged with this boundless machinic subjectivity, plugged into the digital flows of information and desire, Janice, or what is left of her, attempts suicide by jumping off a building, only to discover that UIQ has made her immortal. Raising a bloodied skull from the pavement she pronounces the film’s last line in a voice of indefinite pitch and timbre: “May he give her back her death.”

Of course there isn’t time to explain, describe all this on the phone to Michael. The version of events I pile up like wreckage at his feet is a conflation of multiple drafts, multiple collapses of UIQ’s wave function, each discarded, sloughed off like so many botched avatars as though the problem of UIQ’s individuation had spread to contaminate the film itself. All the mutations and transformations had perhaps begun with a script for a short film about the free radio movement that Guattari had written back in 1977, the year of the Bologna uprisings and the release of both Close Encounters and Star Wars (whose phenomenal success, Michael says, was the result of “a burst of honest enthusiasm”); or else with Latitante, a project on two women fugitives of the Autonomia movement, considered as unknowable “alien” lifeforms whose powers of seduction permit them to move with ease between normally rigidly segmented milieus.

“So what is it now?”

We’ve begun to develop an aversion for the omnipresent signs you see here bearing a whole panoply of orders, laws, statutes and notifying the reader of potential violations and their dire consequences. But often, more than the signs themselves, it is the font in which these interdictions are couched whose violence seems particularly offensive, like the voice of an implacable drill sergeant barking hapless trainees into submission. One of these signs seems disquietingly symptomatic of the irreversibility of US-style modernity. The idea that there’s no going back, no changing your mind, no equivocation—once made, a decision is final. “Do Not Back Up.” The metal teeth are there to rip your regret, your desire, to shreds.

Venice, California. Photo: Graeme Thomson, 2012.

– And when the audiences start dreaming differently, then maybe it becomes possible to make this missing film, even if it’s no longer necessary, because in a way it will be already out there, in the flows of desire, a desire to undo this cosmic catastrophe, this ‘time is money’ mantra that’s destroying everything that lives, to claw the planet back from the predators.

– “…those intellects vast, cool and unsympathetic who regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us…”

– “…and early in the 21st century came the great disillusionment.”

– There you go! Welles didn’t even need to make a film. And his War of the Worlds had a much deeper effect than Spielberg’s. Is this our exit?

We are startled out of reverie by a hot glare of red and blue in the rearview mirror. Rude blurts of siren interspersed with snatches of a choleric alien speech. A UFO has landed. We slow down, not quite knowing how to respond.

– I think they’re telling us to pull over.

If we know the drill, it’s only from the movies. Several minutes of menacing silence and inactivity to stoke our anxiety, before one of the cops gets out of his “vehicle” and swaggers gravely up to the driver’s side. We decide to play the card of the alien. The card of never having seen an American film.

– LICENCEREGISTRATION

– I’m sorry I don’t speak English.

Said in perfectly accented English. Idiot. Not that he seems to have noticed the discrepancy.

– THEN YOU SHOULDN’T BE DRIVING.

Before we have either the time or the temerity to question this line of reasoning, he informs us of the nature of our offense. We’ve been driving too slowly, apparently.

– We only slowed down when we saw your lights. I didn’t know there was a law against driving slowly. Aren’t you supposed to give people tickets for speeding?

This phases him somewhat. He takes it as a cue to retire to his squad car with passport and papers. When he comes back it’s no longer him, but a pumped-up, bullet-headed up incarnation of THE FONT who barks out his intention of taking us to jail for not paying the fine he is about to levy for “DRIVING SO AS TO IMPEDE TRAFFIC,” and for not pulling over when he told us to.

– We couldn’t understand what you were saying. Actually that’s why we slowed down.

– DON’T UNDERSTAND? THERE’S NOTHING TO UNDERSTAND. IT’S THE SAME IN EUROPE. YOU SEE THE BLUE LIGHTS YOU KNOW WHAT YOU HAVE TO DO.

Blue lights? What blue lights? Such a lack of instruction on our part is obviously unthinkable and probably constitutes a more serious crime in his mind than the one we’ve allegedly committed.

– So how much is the fine?

– THAT’S NOT MY CONCERN. ANOTHER OFFICE DEALS WITH THAT. YOU JUST MAKE SURE YOU PAY WHEN YOU RECEIVE IT. OTHERWISE YOU’LL NEVER SET FOOT IN THE U.S. AGAIN.

As he hands us the yellow slip, something in him seems to soften slightly, some Planck length of concern for our well-being, as he offers the parting words:

– YOU KNOW IT’S DANGEROUS TO DRIVE SLOWLY. YOU COULD HAVE BEEN KILLED BY A DRUNK DRIVER.”

We remember the sign and we do not back up. We keep on driving down the freeway. Was it some kind of stubborn slowness that brought us to LA with the UIQ screenplay, 30 years on, or was it “the lightning speed of the past”? And this exposure to light, does it accelerate time, collapse it, or give it another chance, untimely, out of joint?