Crashing Down

by Jörn Jacob Rohwer

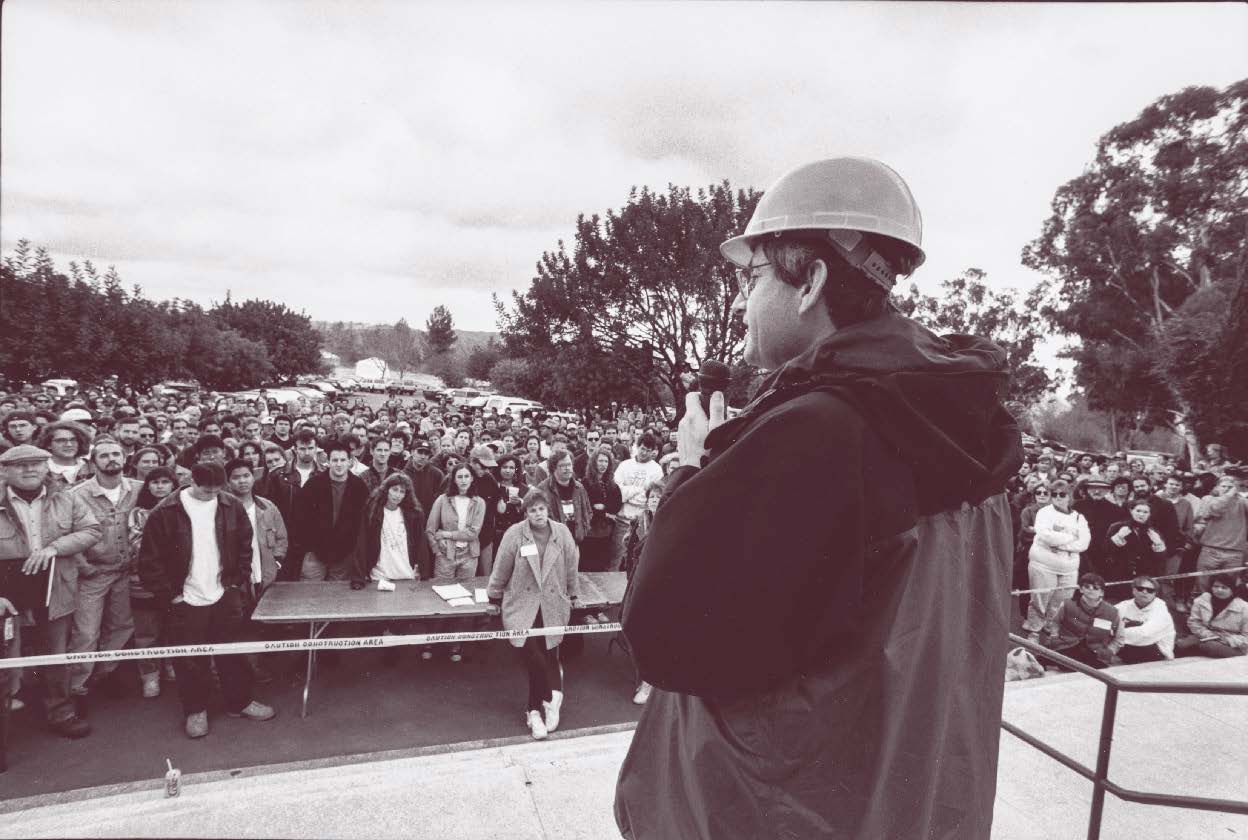

Steven Lavine addressing the CalArts student body, staff, and faculty after the Northridge earthquake, 1994. Courtesy of Deutscher Kunstverlag.

Steven D. Lavine served for 29 years as the third president of CalArts, from 1988 – 2017, following the tenure of his predecessor Robert Fitzpatrick. CalArts at the time of Lavine’s arrival was deeply financially indebted and faced uncertain odds. During the first years of his tenure he oversaw the recruitment of a new generation of academic leadership, and began to stabilize the budget. Then, on January 17, 1994, a magnitude 6.7 earthquake—the strongest in modern Los Angeles history—struck, severely damaging the main campus building. The following text is excerpted from his memoir, “Steven Lavine: Failure is What it’s All About,” published by Deutscher Kunstverlag in 2020, in which Lavine discusses his career, leadership, and life in the arts through a series of conversations with author Jörn Jacob Rowher. Here, he reflects on the Northridge earthquake, the destruction it caused, and how the CalArts community came together to rebuild in the months following the disaster.

Jörn Jacob Rohwer: In early 1994, five-and-a-half years after you had arrived in Los Angeles, CalArts’s situation was widely improved, not just economically. However, on January 17, the Northridge earthquake hit Valencia and basically reduced the campus to rubble. What had seemed like a phase of consolidation turned into a disaster.

Steven Lavine: Unfortunately, yes. When I came to CalArts in 1988 it had an annual structural deficit equivalent to 10 percent of the operating budget. An analysis by the vice president for administration confirmed that we were three to four years from going bankrupt. By early 1994 we’d found ways to control expenses, raise money, and get back to a solid budget—without letting anyone go. We’d appointed a number of gifted new deans, people were behaving civilly to one another (which they had not been when I arrived), and we had recruited many wonderful new trustees. I might have thought my work was done. And then it happened. Janet and I were up in Mendocino about to celebrate her birthday. We heard in a local bookstore that there had been a huge earthquake in Los Angeles. As the L.A. airport was closed, we couldn’t fly back immediately. We had to go to Santa Barbara, where Judy, my secretary, picked us up and drove us to the hugely devastated campus. Gas mains had broken with flames shooting up out of the street, it was one big emergency.

Damage outside Tatum Lounge, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, 1994. Photo: Steven Gunther

Broken dishes in the cafeteria, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, 1994. Photo: Steven Gunther

JJR: Although there was no electrical power and the main building was damaged heavily, you went in and made it through darkness to what was left of your office. That way you could save your Rolodex containing hundreds of addresses and another item precious, though for different reasons.

SL: The Rolodex was going to be essential in the weeks ahead. But then there was also a [Hiroshi] Sugimoto photograph, which I had shipped by Ileana Sonnabend Gallery from New York for Janet’s birthday. I knew that it was in the front office but had no idea whether it had survived the quake. We don’t buy a lot of art; this, for us, was expensive and so I had to find out about it. When I came in, it was still in its packing crate. So both items could be saved…

JJR: … representing very different aspects of personal significance: your wife—and the institution…

SL: … the only aspects that truly mattered to me.

JJR: How did you cope with facing the ruins of what you had worked so hard to improve?

SL: At first I was paralyzed not knowing what to do. Everything needed to happen at once. But no one instantly knows what to do when an earthquake hits. I was lucky we had a vice president for finance and administration, John Fuller, who had lived through previous quakes and knew how to address problems of emergency—for instance, how to get a construction company in to turn off the gas and repair the lines. He became one of the heroes of our stories, insisting on accompanying anyone entering the ruined main building: “If finally someone’s going to get hurt I have to be able to say that I thought it was safe enough to go in myself.” I was impressed he was taking it on [himself] but he (having once been president of a bank that had been robbed) merely replied: “If you have been robbed at gunpoint an earthquake is not so frightening anymore!”

There were hundreds and hundreds of decisions to be made. In the past, I would have worried about them for days; now I had to make them right away. Most people go wrong because they don’t have models of what to do right in front of them. They have to make it up entirely, as opposed to having had a mentor somewhere along the way to point them in the right direction. I had such mentors… And I heard my father say: “All you can do is the best you can do.” If I failed, OK I failed, but I still had to go ahead because I was the president…

Students, staff, and faculty gathered for Steven Lavine’s emergency address, California Institute Arts, Valencia, 1994. Photo: Steven Gunther

JJR: What were the practical implications you had to consider?

SL: What mattered most was to keep the school open and to stay out of the newspaper. It was admission season. If everyone had learned our facilities were severely damaged, students would not enroll. So we had to keep a low profile. I wasn’t ready to ask people for money as we didn’t know the extent of the damage, but I started to let them know that we were in trouble and asked them for advice right away. Within a couple of days I started calling institutions in San Francisco who had gone through the Loma Prieta earthquake five years before. One man who I was put in touch with came down to Los Angeles immediately. I hadn’t even paid for his plane ticket. He came and helped to save CalArts. And the key thing he told us was to have a lobbyist to help us in approaching the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). “FEMA never has enough money for everyone,” he said. “That’s why you need to get a lobbyist to help you make your case in Washington.” Which was exactly what I did.

Once we determined to go ahead with the current semester, it was clear what we needed to do in order to be able to hold classes until we found alternative space. We rented 16 party tents, one for each academic and administrative department. It was very inspiring to see how people, administration and faculty, rose to the occasion. The registrar, for instance, brought her mobile home to campus. It was powered by a generator so she could run her computers and do the registration and financial aid for the semester ahead. The food service was the most damaged part of the building. Though they weren’t supposed to enter the ruins, the food people went in anyway to empty the refrigerators because they knew that otherwise all the food was going to spoil. “What are you going to do with it, how are you going to cook and serve?” I asked, and they replied: “We’re going to cook on outdoor grills and then serve our meals.” Just amazing. I never liked the idea of an army. But here—as people were taking responsibility—it felt like a wonderful thing.

Meanwhile, I had already sent out staff to find rental space. Knowing others would need space too and availability would be limited, I said to them: “Don’t worry about how we’ll use the space, just rent it.” Through this we found 15 properties, but together they didn’t add up to enough room. Our trustee, Michael Eisner, who found spaces for the Walt Disney Company, gave me the number of a man who then identified a disused Lockheed factory only a few miles from campus. Another friend of the school called the State Attorney General who called the head of Lockheed for us, with the result that we could rent the 156,000-square-feet space for eight months for one dollar, which made all the difference.

CalArts is very decentralized, which can be a problem administratively. In the wake of the earthquake though it turned out to be a huge advantage. Once we had space to put everybody in, faculty got their programs up and going again with amazing speed because the schools were used to making their own decisions. Yet many faculty thought that CalArts wasn’t going to survive. They still thought it was too good to be true—the Bauhaus and Black Mountain College hadn’t made it, so why should CalArts, even more so under these circumstances? By the end of January 1995, at our annual board meeting, one faculty member said: “Look, these other schools went down, why don’t we just spend the rest of our endowment, have a good last year or two, and call it quits?” And I replied: “If that’s what you wanted to do, you should have told me before you hired me. Because I don’t have it in me to oversee letting a good thing die.”

CalArts jazz ensemble practices in nearby synagogue after the earthquake, 1994. Photo credit: Steven Gunther

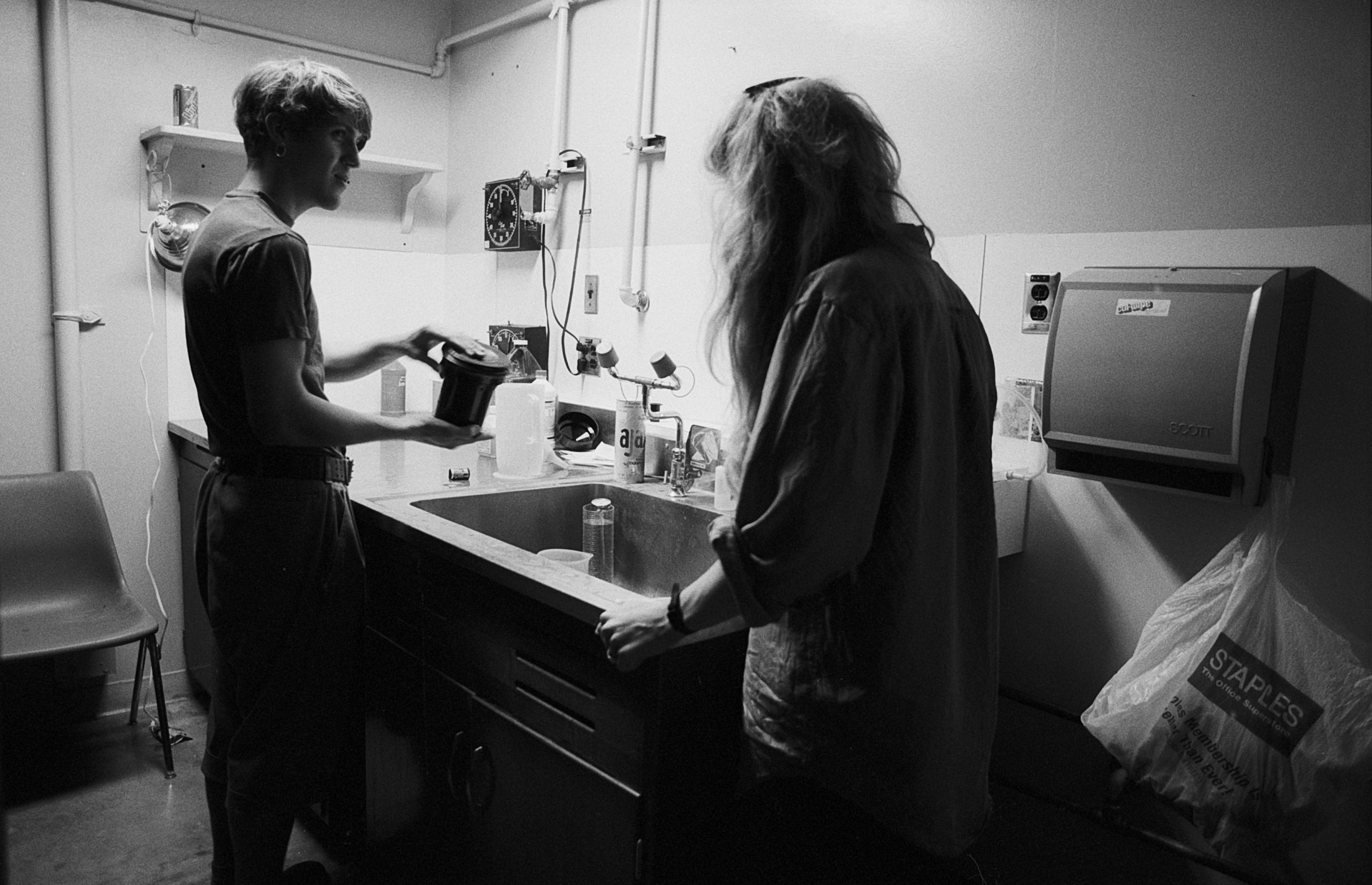

Darell Walters and student work in improvised Photo Lab after the earthquake, 1994. Photo: Steven Gunther

JJR: What did it take for you to generate that kind of strength?

SL: Imagine a child trapped under a car and suddenly you’re strong enough to lift it up and rescue the kid. That’s what it felt like in the beginning. It just was unthinkable that you couldn’t do it. And it didn’t feel particularly heroic, it just was what we needed to do and what I needed to do as the president. The hardest task in the steps towards a recovery was actually a very small thing: as we kept on uncovering more and more damage, the construction company, which had come to our aid initially, wasn’t big enough for the task of rebuilding. It was clear to me we couldn’t keep them. But our vice president, John Fuller, argued that the company had been there when we needed them and now we were going to let them go without sufficient cause. I didn’t just want to overrule John, it took several weeks to bring him around to my understanding of our challenge. But then no big construction company wanted our work. We were in the suburbs, they were in Los Angeles, the freeways were broken and we were going to need hundreds of workers to get the rebuilding done.

My board chair contacted a major developer of the previous generation. He is now retired, mostly doing good work for non-profit organizations in Los Angeles. This man contacted a construction company he had worked with and basically asked the retired head of the firm to ask his son, to whom he had passed on his company, to take our work. What we needed was an open-ended contract promising to provide as many workers as it would take to get the rebuilding done by September 1995, the opening of fall semester, without knowing how much damage there actually was going to be. One aftershock, probably a month later, did another four-million dollars worth of damage. No one would guarantee something like that. And yet this man accepted. It took effort, cleverness, and countless hours of work. At times I was so exhausted that I thought I’d faint. It felt like falling down a hillside without an end. Many months later, when it was all over and done, Janet commissioned a designer to make a beautiful graphic piece for me that I still keep. It quotes a rabbi saying: “I am tired and all my energy is in my tiredness.” As for myself, that was very true… Probably because all of a sudden I saw this place that had served us every day for the past six years savagely wounded. That really took hold of me.

JJR: In Flesh and Stone, a book by Richard Sennett, the author draws an analogy between the human body and the physis of a city. Exemplified by places like Athens, Rome, Cologne, or Paris, Sennett describes the vulnerability of urban space, comparing it to the human organism since both are easily thrown out of balance when their longer-term structures are interfered with whether by natural or human forces. CalArts’s open wounds and your reaction to it reminded me of this.

Damaged ceiling above the Super Shop, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, 1994. Photo: Steven Gunther

SL: When I came in on the second or third day after the quake, I could see that there was dust from the concrete at the base of the columns of CalArts’s huge central hall. Initially I thought it was from termites. Then I learned that the steel had been so twisted that it was ground concrete as the steel tried to return to its original alignment. This seemed quite striking to me—that it was trying to restore itself, like a living creature. I also remember how it terrified me when, by pulling back the skin of the building, we could see the damage done within: everything was torn and splintered, it really looked like wounds, these big, diagonal cracks in the heavy blocks of concrete. Some of the concrete was so torn you could see through the walls. On the outside of the building, openings had appeared. The sight was quite dramatic. And yet we were assured the building wasn’t going to collapse. It was clearly unsafe, but held up by its own structure and weight.

As the construction workers made their way through the multiple wings to the center of the main building, they uncovered more and more damage. At first it was14, then 20, then 28, then 32 million dollars we needed for the rebuilding—it kept going up and up and up. We had been so broke as we’d fought our way back that we’d been basically worried about every five-hundred-dollar decision. And suddenly, without any real security back-up, we were forced to spend millions! But we knew we just had to keep going if we were to have any chance of saving CalArts. Had there been a thorough analysis of what needed to be done before the reconstruction, we would have lost four months and wouldn’t have been able to get everything rebuilt in time to enroll a fall class, which would have meant other layoffs, and many more millions of losses. The way we had it done was painful, but at the same time an exciting experience because everything we did was new and there was lots of reaching out and learning for all of us to do.

JJR: Given that 25 years [sic] have passed since then and new students are coming to CalArts continuously, having no idea that once their campus had lain in ruins—is there any lesson you’d like to be passed on about this particular history?

SL: I guess it’s that we just did it. There was no text to tell us what to do. The biggest challenges come down to common solutions. Big problems are often just a bunch of small problems combined and you don’t have to be afraid of them, you just go through it. I’d also like to have remembered that CalArts had a structure that often seemed chaotic to people but in fact worked beautifully, even without clear lines of authority, because people took responsibility. That’s the true reason why we didn’t end like the Bauhaus or Black Mountain College. When there’s a disaster you often hear: “We’re going to emerge stronger than before.” Well, we actually did become stronger. Two or three faculty left town altogether; they didn’t even tell us they were leaving, the fear of the earthquake being just too much for them. Even though I understand you can’t have control over something that is terrifying, it was hard to be sympathetic, even more so as I saw what a community is capable of when it pulls together. We never would have built REDCAT if it hadn’t been for the confidence that arose from our successful recovery from the earthquake. We didn’t have enough money when we started to build REDCAT, but we knew it was important for the future of CalArts. And so we did it. And emerged with a whole new level of self-confidence. A “we’ve gotten through that, now we’re getting through this.” It’s an inheritance that still lives at CalArts and, I hope, will prevail.

JJR: It seems to me that it took the Northridge earthquake for you to prove that you were not just a scholar trying to run an institution, but a loyal man ready to act, to take risks and responsibility in a huge crisis and, by doing so, save CalArts’s physical existence.

SL: I never really trusted myself until the earthquake had happened and I never really felt worthy to be alive until after we recovered from it. Along with Janet, the Northridge earthquake is the most important thing that’s ever happened to me. I guess if St. Peter at the pearly gates should ask me: “Why should I let you in?,” I’d say: “Because I was at CalArts and didn’t run away.”

During my first years I’d assume that people would think what right did I have to be a president without having worked my way through the steps of academic management… I always felt like there was this hole under me. And suddenly, when it was all over, there was no hole anymore. I felt like I had grown up, like I had passed my final exam. I have a tendency to depression, but I didn’t let it stop me, I just carried on. We all just kept going as we all gained weight eating donuts all day long just to stay warm and keep up the energy.

Construction in Langely Courtyard after the earthquake, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, 1994. Photo: Steven Gunther

There was this wonderful moment when I went into my office with Judy McGuiness and a second secretary. My predecessor, Bob Fitzpatrick, had left all sorts of liquor bottles in the shelves—I think he entertained more than I did—and they’d fallen down and were all broken. There was a terrible mess on the floor, everything was a mess. And we just began to clean it up. And at one point I looked up and said: “Look, what we’re doing…!” And Judy said: “Yes, I guess we’re just good workers.” And that seemed like a great thing to be—a good worker.

JJR: What’s your definition of a “good worker”?

SL: Judy, being 30 years at my side, is a good worker indeed. Totally self-respecting, always good-spirited, doing what had to be done, even working late—an exceptional person. In those days we would have student protests about one thing or another and I remember Judy calling me to announce some protestors coming up from the theater school: “You should know they brought some friends…” And I could hear from her voice that it was a lot of “friends”—in fact, it was the entire student population of the theater school all coming into my office until it was packed with people cheek to cheek. One of them said: “We just wanted you to know what overcrowding feels like.” Then they all left, except for three or four with whom we sat down and discussed the situation. Any other secretary would have said: “There’s a terrible protest out here, maybe we should call security!” Not Judy, she was just totally unflappable whatever happened. I could just trust her. Trust is, in some way, the most important thing in a person you work with. Sometimes, especially in the last few years, I was cranky a lot; I think I was getting tired. And Judy just put up with me even when she heard me in there swearing to myself. Judy is not someone who’d swear or use that kind of language. But it didn’t alarm her, she just knew we were on the same side. Valuing people for what they can do and not rejecting them for what they can’t is one of the great lessons of CalArts for me. Because there is no perfect person for any job. We are all imperfect.