Decorative Arts: Billy Al Bengston and Frank Gehry discuss their 1968 collaboration at LACMA

by Aram Moshayedi

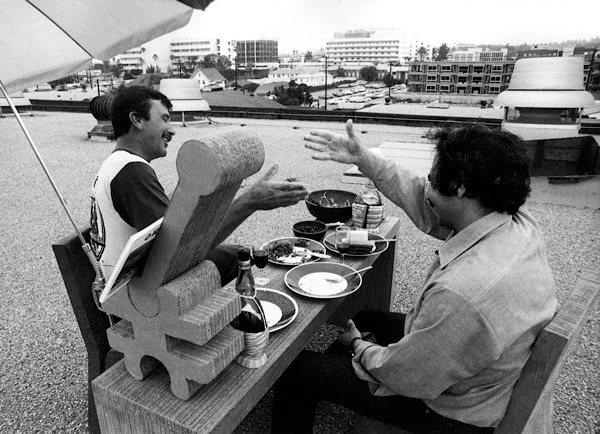

Billy Al Bengston (left) and Frank Gehry (right) on the rooftop of Gehry’s office in Santa Monica, ca. 1970. Photographer unknown. Image courtesy of and © Billy Al Bengston.

On the occasion of a ten-year survey of his paintings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1968, artist Billy Al Bengston enlisted the help of architect Frank Gehry to design the exhibition’s scenography and create an architectural armature upon which the show could hang. Complemented by a now rare and coveted catalog by Ed Ruscha, Bengston’s presentation at LACMA proved to be the most substantial articulation to date of the painter’s commitment to the context of display as a form of mediation and experience. The exhibition design included reused discarded wall fragments from the museum’s past exhibitions, borrowed furniture and home accents, posters from the Black Power movement, and a life-size wax figure made in Bengston’s likeness by the nearby Hollywood Wax Museum. In retrospect, the paintings appear to almost be an afterthought in an installation conceived and executed by two friends and collaborators, one that privileged the conditions under which pictures are viewed, and sometimes overlooked, in the conventions of museology.

The following conversation took place at the Santa Monica office of Gehry Partners in the summer of 2012. Reflecting back on a relationship that has spanned nearly five decades, it provides an opportunity to consider early collaborations between artists and architects, the genealogy of artistic trends that sought to expose the limitations of painting and the mediating principles of museum display, and the ways in which Gehry’s and Bengston’s practices have been historicized and understood as part of an inherently formalist brand of art in Los Angeles.

ARAM MOSHAYEDI: Let’s talk about your collaboration at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1968. Although the exhibition was billed as a ten-year survey of Billy’s paintings, it’s clear that Frank’s exhibition design was dominant and central to the execution of the show. How did the idea for this collaboration come about?

FRANK GEHRY: To start, there was no budget. We had a museum director, Ken Donahue, who was a nice, bumbly guy but a dinosaur in terms of the art stuff that was going on. His curator was none other than Maurice Tuchman. I think probably Billy proposed me to them.

BILLY AL BENGSTON: No, I didn’t propose anything. I said, “He’s doing it.”

FG: I was a hanger-on to the art scene because the architects that I was collegiate with at the time thought I was nuts. Even my friends at the time and those who are still my friends—some of them are dead—thought I was weird, but I didn’t know I was weird. And when the art guys embraced me, I was declared weird by association probably.

Installation photo of Billy Al Bengston’s exhibition at LACMA, 1968. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

AM: Did the architecture world not offer the same kind of support network that the art world seemed to provide?

FG: Well, I probably could have found the support, but it probably would have been a disaster for my life if I had gotten it. This way, I became somebody that was freer. They didn’t know they were opening these paths for me, and I didn’t know it at the time. I was like a blotter, and I was just picking up on the kind of willingness to experiment, to go where nobody went, to try things and not be able to explain them.

AM: Billy, for this project at LACMA, what was the attraction you had toward collaborating with an architect, Frank, rather than another artist?

BAB: Well, let’s put this in perspective. I can tell you, it was a very small world, and Frank is only telling you about what happened in his world. In our world at that time, I shared a studio with Ken Price, and we worked and we smoked cigarettes and drank black coffee. That was it. For lunch, he’d have a Heath bar and I’d have a Snickers bar. That was it. Then we got a ping-pong table, so we’d surf, play ping-pong, and work, smoke and drink black coffee. That’s it. That was what we did for three or four years. That’s all we could afford to do. It was a very small world. At that time, there were so few interesting people that there was a gravitational pull, and Frank was part of the interesting people. None of us knew at the time that he thought anything of us. And we didn’t know that Frank was going to become the foremost artist of our time. AM: Tuchman once mentioned another exhibition that you worked on at LACMA called “Art Treasures from Japan.” Did you do exhibition design for many of the shows there?

BAB: He did a lot of exhibitions at LACMA, and they were all very conservative until he got to me.

FG: I’ve told this story a million times, but the architecture teachers at USC in the 1950s were returning GIs—architecture graduates but who had been in the army. They saw Japan and all those beautiful temples in Nara and Kyoto. And the language was transportable, so they had an aesthetic that they could transport and build here quickly. Greg Walsh, who became my partner, had lived in Japan during his navy tenure and was totally a Japanophile, so when the LA County Museum was given “Art Treasures of Japan” to do, they asked us to do the installation. Walsh was close friends with the curator of Asian art.

Installation photo of Billy Al Bengston’s exhibition at LACMA, 1968. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

AM: Did the success of that project lend some credibility to the idea of collaborating on Billy’s show?

FG: The curators at LACMA knew I could get it done, but they were worried because at the time I was using plywood, chain-link, corrugated materials, and things like that in my designs. They said there was no budget to buy materials and that I had to work pretty much in the norm. So I asked them to take me down to their storeroom, where they had piles of plywood with paint on them. I asked what they were doing with the plywood and they didn’t know, so I took it and made his exhibition.

AM: So the colors throughout the installation were entirely inherited from the recycled materials?

BAB: Yes, they were all random and placed randomly. At that time, the museum would put up temporary plywood walls, which would be painted depending on the show. There was a lot of leftover paint in powder blue, as I recall. Quite a bit of rust, a little bit of yellow, and then some natural. So Frank designed this thing, but when the museum started putting up these used walls, they said to me, “Don’t worry, we’re going to paint them.” But I said no, and then Frank showed up.

FG: They thought I was going to want them painted, but I didn’t. The day that [LACMA director] Donahue finally came in to see it, I think he almost had a heart attack.

AM: You mentioned Maurice Tuchman before as the curator, but didn’t James Monte also play a part in the curation of the exhibition?

BAB: Monte was the curator that was called on, but actually Tuchman did it. He was the head curator. But as far as I’m concerned, nobody curated the show.

FG: No, there was nobody. We did the show ourselves, and it was super. It was serendipitous that I went down, found the goddamn plywood, and pulled it up; and it was cheap so they couldn’t deny it. They didn’t have any money to do anything new, and I said we would use the old materials. I guess maybe I told them we’d paint it, but then when it got up it looked so great that we kept it up. It scared Tuchman a bit, but at the time he was pretty willing to try things.

BAB: I didn’t have any problem with Tuchman at all.

FG: No, he was open to stuff, and he knew artists. He knew how artists worked, so he was relatively supportive.

AM: The idea of creating a space that resembled a studio or a domestic space in the context of a museum seemed to be a radical gesture, but also, Billy, in terms of how your paintings are understood and discussed, the exhibition at LACMA seems to stand out as an attempt to control the reception of your paintings, to define the space in which they were viewed. Did you consider this gesture as a response to the conventions around the display of paintings within the museum?

BAB: It wasn’t radical at all. The point is that at the time nobody walked around a museum with earphones, and there was no definition of what everything was or meant. Today, everything is spoon-fed, but in those days you had to look. Today, nobody looks. They just listen and walk around and bump into other people. But even then, nobody actually got close enough to see anything. They’ve always just stood back at a certain distance to look at something on the wall. That’s the reason I wanted to install my work in the way that we did. The experience of going to a museum is a totally synthetic situation—walking around, looking at things, standing on your feet. The best a museum does is to put in one these uncomfortable benches in the middle where they don’t belong.

Installation photo of Billy Al Bengston’s exhibition at LACMA, 1968. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

AM: You mentioned before that there was no real curatorial oversight at any point in the exhibition, but it also seems like you were both taking liberties that weren’t necessarily consensual or that Billy, in particular, wasn’t even aware were happening despite the fact that it was his paintings that were the intended objects to display.

FOG: It wasn’t that Billy wasn’t in control. If he said no, it wouldn’t have happened.

AM: From what I’ve read about the installation, it seems that there was an issue about the furniture. Was there a disagreement between the two of you about the function of the furniture in the show?

FG: The biggest and only real issue happened with the furniture. I assumed Billy would help me get the furniture for the installation, but he didn’t at first. He said he didn’t want to be any part of it and that he didn’t even want to hang the show. But Tuchman said that he had to finish the installation, and we still hadn’t brought in the furniture we said we would. I didn’t know where to find the furniture, so somebody in my office suggested that we rent it, and that’s what we did. We called a rental place and asked for four living rooms. I just said to bring whatever kind of furniture was popular at the time.

BAB: I assumed you said whatever was the cheapest.

FG: I didn’t pick the furniture; they just sent four living rooms and put it all in the museum. Tuchman called me and said that I had made the greatest artwork ever but by accident and that it wasn’t relevant to this show. At that point, there were still no paintings installed, so to take average furniture like that, put it in a museum, and set up living rooms—it looked like some kind of tableau that I don’t know who would’ve done. By accident it was very powerful but also very irritating. The furniture was in your face.

AM: Would it have potentially outdone the paintings?

FG: It was just this funny plywood environment with funny carpet and then this furniture.

AM: Ed Ruscha later said that it felt too much like home.

FG: That was in regard to the installation after. He didn’t see the first sets of furniture. Nobody saw it except for Tuchman, who was freaked on two levels because it did something by accident—I didn’t design it—and it made a statement other than what we intended to make.

We tried to get it out of there before Billy saw it, but we weren’t so lucky. Billy saw it and didn’t get an explanation that it was a mistake, so he thought it was my idea to do the furniture in that way. He started yelling at me and calling me all kinds of things. It freaked me out because, as you can imagine, I loved Billy. I wanted to make this the best thing ever for him. I was worried about bombing in their world because of this thing. If I bombed, they wouldn’t let me in anymore. There was a lot riding on it for me. It was a heavy thing. And when he came and started yelling, I just—

BAB: I just said, “Get this shit out of here.”

FG: Then he just did it on his own.

BAB: I borrowed all the furniture.

FG: He did what we wanted to do in the first place, and it was great. I had spent all those years at Billy’s studio, and every month he would change the decor. The biggest tragedy is that we didn’t photograph all of his stuff. Talk about a decorator— I wouldn’t want him to be considered a decorator, but that’s where I learned a lot about my own aesthetic, by watching him change his studio all the time.

AM: Was the objective of the installation to turn Billy’s paintings into a form of decoration? Billy, do you have problems with your painting practice being described as decoration?

BAB: I don’t have a problem with that.

AM: It’s obvious that you consider the paintings as secondary objects.

BAB: The paintings are secondary until you sit down and look at them. When I was younger, I thought I was making something new, but the only thing I was doing was reinterpreting the materials and making a decorative object that didn’t have a specific meaning. Paintings are primarily decoration until you sit down and look at them, and most paintings, if you put them in the wrong light, don’t look how they were intended. If a painting needs a light fixture or if it needs a certain wall or something, then it is another thing entirely. So my thinking was to make something that does not need any specific kind of light.

Installation photo of Billy Al Bengston’s exhibition at LACMA, 1968. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

AM: Where did the idea of including a life-size wax model of Billy come into the plan for the exhibition?

FG: Just by accident one night at some party in Hollywood with John Altoon, I met this guy named Spoony Singh, who owned the Hollywood Wax Museum. We all got drunk, and I told him about the show, and I told him about Billy. In my mind, Billy was a big thing—I thought everybody knew who he was—but this guy didn’t have a clue who Billy was. He did it anyway, though.

AM: Did Spoony Singh see any significance to a show at LACMA even if he didn’t know who the artist was?

FG: No, not at all. I told him after the show he could put it in the Hollywood Wax Museum, but he just looked at me. I assumed he would be interested, but he wasn’t. He just made the wax figure, and that was it.

AM: What was the little figure placed right next to the wax figure of Billy?

BAB: A friend of mine who was an acolyte racer gave it to me at the show’s opening, so I put it down there. I have no idea what it is. It’s a little sculpture of me going into a turn on a motorcycle; it was his concept. I don’t even think Frank knew about it.

FG: That’s the first time I’ve seen it.

BAB: Frank hasn’t yet mentioned the foremost part of the exhibition—the guards, who inevitably were a pain in the ass in those days. I happened to be very involved with the Black Power movement so I made decisions that were based on my relationship with the guards, who at the time were mostly black. I put in a comfortable couch, a television set, and where some of the walls were not open, I took out the plywood so they could see everything in the exhibition without having to move off the couch.

Installation photo of Billy Al Bengston’s exhibition at LACMA, 1968. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

AM: And how did the guards respond to this?

BAB: They were responsive in part because a little section in the exhibition included a lot of Eldridge Cleaver posters and stuff like that. But I also had full run of the museum, which is entirely different from today. I could come in at midnight and do everything myself without needing to ask anyone for anything. I would come in at any hour of the day and night because I got access without having to go through the curators or anybody, and I could do damn near anything I wanted to.

AM: Even though it would be contrived to situate this project within the context of institutional critique, it seems as if there was an attempt to address the specific context and conditions of museum display. The exhibition seems inherently antagonistic and self-critical, perhaps even foreshadowing a brand of work that came of age in the 1970s. Would that seem accurate now in retrospect?

BAB: That’s interpretation.

AM: It’s also a historical fact.

BAB: Of course, but really what we were trying to do was to make chicken salad out of chicken shit because we were forced to do so. Studios function that way. A studio is a place where you can take a piece of shit and think of how to fix it.

AM: But, specifically, what you are describing with this exhibition is an engagement with the conditions of painting, rather than the history of painting itself—describing your paintings as though they are almost a byproduct of the way you consider museum lighting, for example.

BAB: In a way, they are.

FG: It seems that they could have been painted anywhere because Billy realized at an early moment how Hollywood and the media had overpowered the whole world and changed the lives of everyone. He got into it for a minute and couldn’t take it. He realized what it was, so he slammed the door on the whole thing. Some of us knew how to manage it, but Billy just wanted to be left alone. He couldn’t deal with it.

AM: Do you think part of this was about undermining some kind of significance that a ten-year survey was meant to imply? I remember you once saying that your original idea was to make your paintings available in bins for visitors to rummage through, for instance. That idea and what you ended up doing at LACMA seem like a withdrawal from participation or an attempt to not play the game. Is it that you weren’t really even interested in doing a show with the museum?

BAB: Well, showing didn’t mean anything. It really didn’t, I don’t think. The things that mattered to me was that Ruscha did the catalog and got paid for it and Frank did the installation and got paid for it.

AM: Frank, do you remember what you were paid?

FG: Maybe $2,000.

AM: And, Billy, did you get paid for your part?

BAB: No, and the museum didn’t buy anything. At the time, there was really nothing to be accomplished in the art world. If you go back and look at the financial records, you’ll see that nobody was making any money and nobody had fancy studios.

FG: I think all of us had tendencies to be self-destructive because of our insecurities about what we were doing. We didn’t know what we were doing.

Installation photo of Billy Al Bengston’s exhibition at LACMA, 1968. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

AM: Do you think the fact that LACMA had a relatively short history by 1968—that it had been in that location for only three years—had anything to do with your ambivalence? Did this new institution afford you both the opportunity to think about what the display of culture meant in a way that had never existed in the city before then?

FG: Sure, putting the work in LACMA gave it credibility.

BAB: You have to think that way when you walk into a place that looks like that.

AM: Do you mean that it is a place that’s not made for you, not set up, say, how a studio is set up?

FG: In the case of the Guggenheim in Bilbao, I worked with a brilliant director and it was always about making a place with the art in mind. But after it opened, there was a museum directors’ meeting in London where they passed a resolution to never build museums like that because it was architecture competing with the art. I didn’t get another museum for a long time after. People like Glenn Lowry would say publicly: We don’t want another Frank Gehry. But artists like Cy Twombly would call me from Bilbao and say that their show there was the best they’d ever had. Hockney sent me a nice note about it, and Rauschenberg liked it, so there was a kind of disconnect from what the museum directors said. The artists always told me that they didn’t want sterile white rooms; they wanted something to work against. But museum curators and directors just want the white cube because it’s easy to do and they don’t have to think. They just go and put it up and get out, and it’s cheap to change from show to show. Some stuff just dies in that environment.

BAB: The only thing that doesn’t die in that environment is stuff that’s designed for it, and that is no good.

AM: You mean that a kind of work that is made with its presentation in mind?

FG: I was on Charlie Rose a few years ago with Renzo Piano, and Charlie was trying to figure out the difference between Renzo’s work and mine as far as museums. He said the rap on me is that my museums compete with the art and, of course, the other two architects on the show came to my defense and said, oh no. But Charlie still pressed, so I said the marketplace decides. And he looked at me and he said, “What do you mean?” And I said, “Well, I did Bilbao, and I never got another museum.” So he turns to Renzo, and Renzo kind of shrugs on camera, and I say, “The defense rests.” That’s on camera. Then Charlie asks, “What about the artists? Don’t they weigh in?” And I said, “Look, if you’re an artist and the Museum of Modern Art is going to give you a show, you’re not going to complain.” When the taping of the show ended, guess who is sitting in the front row? Ellsworth Kelly. And he came up to me and said, “You’re goddamn right. I hate MoMA.”