Do You Believe in Television? Chris Burden and TV

by Nick Stillman

It’s generally known that Chris Burden made a few commercials for television in the 1970s. But any pursuit of why, expanding meaningfully beyond the descriptive synopses Burden himself provides for most of his individual works, has been curiously rare.

Chris Burden, still from TV Hijack, 1972. Photo: G. Beydler. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery, © Chris Burden.

It’s generally known that Chris Burden made a few commercials for television in the 1970s. But any pursuit of why, expanding meaningfully beyond the descriptive synopses Burden himself provides for most of his individual works, has been curiously rare. Burden—then living in Venice Beach—was concurrently making live performance work that deployed television monitors as critical signifiers of voyeurism. This link between his use of the television set as an object or prop in performances like Do You Believe in Television or Velvet Water and his works that actually took place on television is crucial to parsing why arguably the foremost performance artist of his generation began to resituate a live performance practice to a medium that seems antithetical to live art. Television as both communicative and manipulative vessel is a major focus in Burden’s work from 1971 to 1977. Burden usually downplays the political connotations or intentions of his art, but this body of television work seems like an examination of militaristic training, specifically, how authority results in belief.1

Since its inception, television has been the facile target of the moralizing intelligentsia, condemned in trenchant theoretical analyses and flippant blog rants, and this essay is not intended as another anti-TV-culture screed. Rather, it will attempt to chart how Burden’s works for and about TV function as controlled psychological experiments. Burden used TV sets in performances as decoys, implicit endorsements of passive voyeurism; an audience would find itself alienated from a dangerous situation or an endangered performer by viewing these things through the isolating remove of the screen. When his commercials were aired within a block of other “real” ads, they, per Burden, “Stuck out like a sore thumb … I had the satisfaction of knowing that 250,000 people saw it every night and that it was disturbing to them, that they knew something was amiss.”2They broke with the patter of the form. Burden’s work in this vein asked viewers to identify for themselves when authority is arbitrary, even when Burden himself could be considered the authoritative figure.3Something that should be starkly clear is that I don’t think Burden’s TV work was anti- (or pro-) television. It was appropriating the metaphor of television to create experiential environments designed to ask people why they believe what they’ve ended up believing.

By the 1970s, academic studies had shown that heavy television watching was detrimental to mental development and creativity and that it promoted delusional thinking. A 1975 study by Dr. George Gerbner and Dr. Larry Gross of the University of Pennsylvania found that “heavy viewers” of television in America were more likely to overestimate the percentage of the world population living in the US, the percentage of the population with jobs, the number of cops in the US, and the amount of violence in the US. In other words, they were more likely to believe what they were shown on television. In his assault on the medium Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, the former adman Jerry Mander noted that by the beginning of the 1970s, television had become “the main transmitter of reality,” and that individuals cognizant of this—from Richard Nixon to the Symbionese Liberation Army to corporate advertisers—expertly manipulated it for political and capital gain.4Sensing the insidious corporate stronghold on the medium, but also its communicative and activist potential, Burden and other artists in the 1970s went beyond critiquing television; they began using it as a medium for their work.

Assuming from the outset that Burden’s TV work was acutely informed by the manipulative mechanics of mainstream television, he can to some extent be situated within a circle of artists, collectives, and media critics in the 1970s who aimed at revealing the monster behind the seemingly benign screen. Some collectives advocated for public access to technology that could transform television consumers into producers (these groups included Videofreex, People’s Video Theater, and the Raindance Corporation), while several individual artists attempted to deconstruct television’s psychological grip on viewers by appropriating both its frame and its product.5For me, the most interesting in addition to Burden’s works are Bruce Nauman’s disorienting Performance Corridor installations, where what is visible onscreen doesn’t correspond with reality, and Dara Birnbaum’s appropriations of television—Technology/Transformation; Wonder Woman (1978–79) or Kiss the Girls: Make Them Cry (1979)—that expose its hypnotizing, deadening effects. It’s important here to differentiate how these visual artists approached television from the ways in which the previous generation—epitomized by Warhol’s brand of Pop—did. For, as much as it is my belief that Warhol’s celebrity-soaked work was intended to reveal the ludicrous depths of America’s obsession with the icons of capitalism (its judgments on that depth of obsession are where it gets murky), it essentially just reimaged it. A Warhol silkscreen may defamiliarize a familiar image, but its relationship with the viewer remains a consumptive one—like the television, it is there to be gazed at. On the contrary, Burden’s work in the 1970s confronted, rather than emulated, the consumerist ethos that found its highest (or perhaps just its most convenient) expression in the televisual experience.

Burden’s commercials are the most broadly known of his TV works, but his first appearance on television was actually a live broadcast. In early 1972, the art critic Phyllis Lutjeans invited him to propose a performance for cable TV Channel 3 in Irvine, California. Subsequent proposals were, according to Burden, “censored by the television station or by Phyllis” so instead he acquiesced to a live, televised interview by Lutjeans. Burden brought his own camera crew to document the event. The reason for this became evident when Burden sprang up from his chair, held a knife to his interviewer’s neck for the next several minutes and “threatened her life if the station stopped live transmission.”6Later reminiscences by Lutjeans seem to prove that there was no predetermined collaboration.7The lone extant “action” photograph (several still photos were shot before the death threat) shows Burden grabbing Lutjeans’s bun of hair with one hand and positioning the knife’s blade across the middle of her throat, so close that it appears to touch her skin. When the recording session was stopped, Burden requested the station’s tape and destroyed it with acetone. His own camera crew’s tape of the performance TV Hijack remains the only remaining live recording.8

Chris Burden, still from TV Hijack, 1972. Photo: G. Beydler. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery, © Chris Burden.

TV Hijack is a declaration of agency. Burden got to do a performance live on TV after all, and he didn’t adjust it to fit a homogenizing TV frame. The medium was borrowed but the message was his. Burden expounded on television art during the next five years with four commercials—almost masquerades of advertisements—made for broadcast on television. The first of these—TV Ad—remains the most infamous. Using a video recorded excerpt of Burden’s 1973 performance Through the Night Softly, the ad is a 10-second black-and-white spot that was broadcast five times a week for four weeks on KHS-Channel 9 in LA for a month during November and early December of 1973.9Incredibly, it was aired in a prominent slot just after the 11 pm news. The first three seconds of TV Ad are exclusively text—bold letters spelling out “CHRIS BURDEN” against a black background, then handwritten script reading “THROUGH THE NIGHT SOFTLY” against a gray field. Then comes the footage of Burden, who wears only bikini briefs and whose hands are tied behind his back as he crawls on his stomach through broken glass scattered on a sidewalk in downtown Los Angeles, grunting as the shards crunch underneath his body.

Burden speaks frankly about his motivations (though not necessarily about his intent) for making TV Ad in a compilation video in which he discusses his early 1970s works:

The TV Ad piece came out of a long-standing desire to be on television. The more I thought about it, the simplest way seemed to be to purchase a commercial advertising slot. Acting on that, I pulled out the yellow pages and started calling up TV stations to get their rates. I could only afford to purchase a 10-second spot ID. My biggest problem was convincing the station that I was worth bothering with, that I was a legitimate artist.10

After the notoriety of Shoot (1971), Burden’s performances had begun to attract audiences expecting something dangerous or spectacular–a less than optimal climate in which to do something unexpected. By situating an artwork on local television, Burden all but ensured he would reach an audience with no previous knowledge of his work.

Burden’s next advertisement was the weird, mystifying spoken word-style Poem for L.A., where the stoned-looking artist intoned “Science has failed / Heat is life / Time kills” either one or three times depending on whether the station was running Burden’s 10- or 30-second spot. Bizarre, but not so out of step with the beatnik vibe that had become more or less mainstream by 1975. The final two ads are the most interesting. Chris Burden Promo was a 30-second spot that ran 24 times on New York’s Channel 4 and Channel 9, and 21 times on the Los Angeles channels 5, 11, and 13, in September of 1976 during peak viewing times. Whereas all of Burden’s ads require some degree of reading, the visuals for Chris Burden Promo were exclusively text. Five artists’ names appeared in succession on the screen, each fading in until it filled the screen horizontally, at which point Burden spoke them aloud: “LEONARDO DA VINCI, MICHELANGELO, REMBRANDT, VINCENT VAN GOGH, and PABLO PICASSO.” The names were chosen as the result of a survey that showed them to be the most recognizable artists’ names to Americans. The last name to appear onscreen was CHRIS BURDEN, followed by the text “PAID FOR BY CHRIS BURDEN – ARTIST © 1976.” This last morsel of information is the crucial one, where Burden forthrightly declares that the absurd–too absurd even to be considered self-aggrandizing–message came straight from him. In other words, Chris Burden Promo is Burden’s tidy subversion of how quality is normatively mediated in the art world: through critics, curators, and galleries. Burden instead hews to the corporate advertising paradigm of assigning quality to yourself by suggesting favorable associations. Corporate self-aggrandizement on television is perfectly normal, expected even; coming from an individual, the behavior seems hilarious or delusional. Either way, Chris Burden Promo must have made the advertising surrounding it seem awfully exposed.

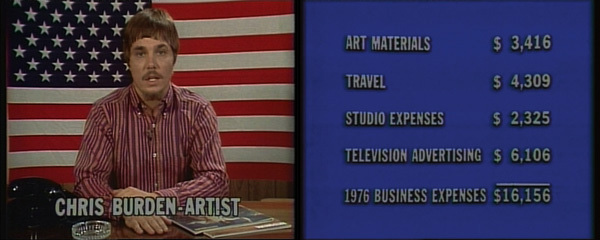

Chris Burden, stills from Full Financial Disclosure, 1977. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery, © Chris Burden.

Burden’s final ad upped the parodic ante. For the 1977 piece Full Financial Disclosure, he became, in his words, “the first artist to make a full public financial disclosure.”11In a short video, Burden faces the camera while seated at a desk in front of a huge American flag that dominates the background. With a caption identifying him as CHRIS BURDEN – ARTIST, he delivers a deadpan monologue in the style of a sincere politician demonstrating his post-Watergate financial transparency. Following the brief statement, a series of graphics silently flashes onscreen, revealing Burden’s gross income for 1976 ($17,210), his business expenses for the year ($16,156), and his 1976 net profit ($1,054).12Burden’s short speech at the beginning of the commercial was: “In keeping with the Bicentennial spirit, the post-Watergate mood, and the new atmosphere on Capitol Hill, I wish to be the first artist to make a full public financial disclosure.” Whatever expectation there may have been that a “name” artist like Burden automatically lived comfortably is certainly eliminated if we’re to accept Burden’s accounting at face value. This was seemingly corroborated three years later in his KPFK radio piece Send Me Your Money, in which he asks listeners to “imagine the possibility of sending him money” because “I don’t have very much money and I could use more.” He even references Full Financial Disclosure during the hour-long radio solicitation and reminds listeners of his paltry income in 1976.13Buried within Full Financial Disclosure’s thinly veiled political parody was the fact that Burden revealed exactly how much money he had spent on television advertising in 1976—$6,106—a little over 35 percent of his income. It’s difficult to discern exactly what the costs per ad were (Burden may have still been paying for his 1975 ad in 1976, or even the upcoming 1977 one), but it’s clear that for an individual, television advertising is expensive. By revealing—on television—how television stations make their profit, Burden used television against itself to break an unspoken industry taboo. Of course television advertising costs money—but exactly how much tends to be inaccessible information; this is the domain of corporate entities. Full Financial Disclosure is a 30-second portrait of one man’s dalliance in a realm where he doesn’t belong.

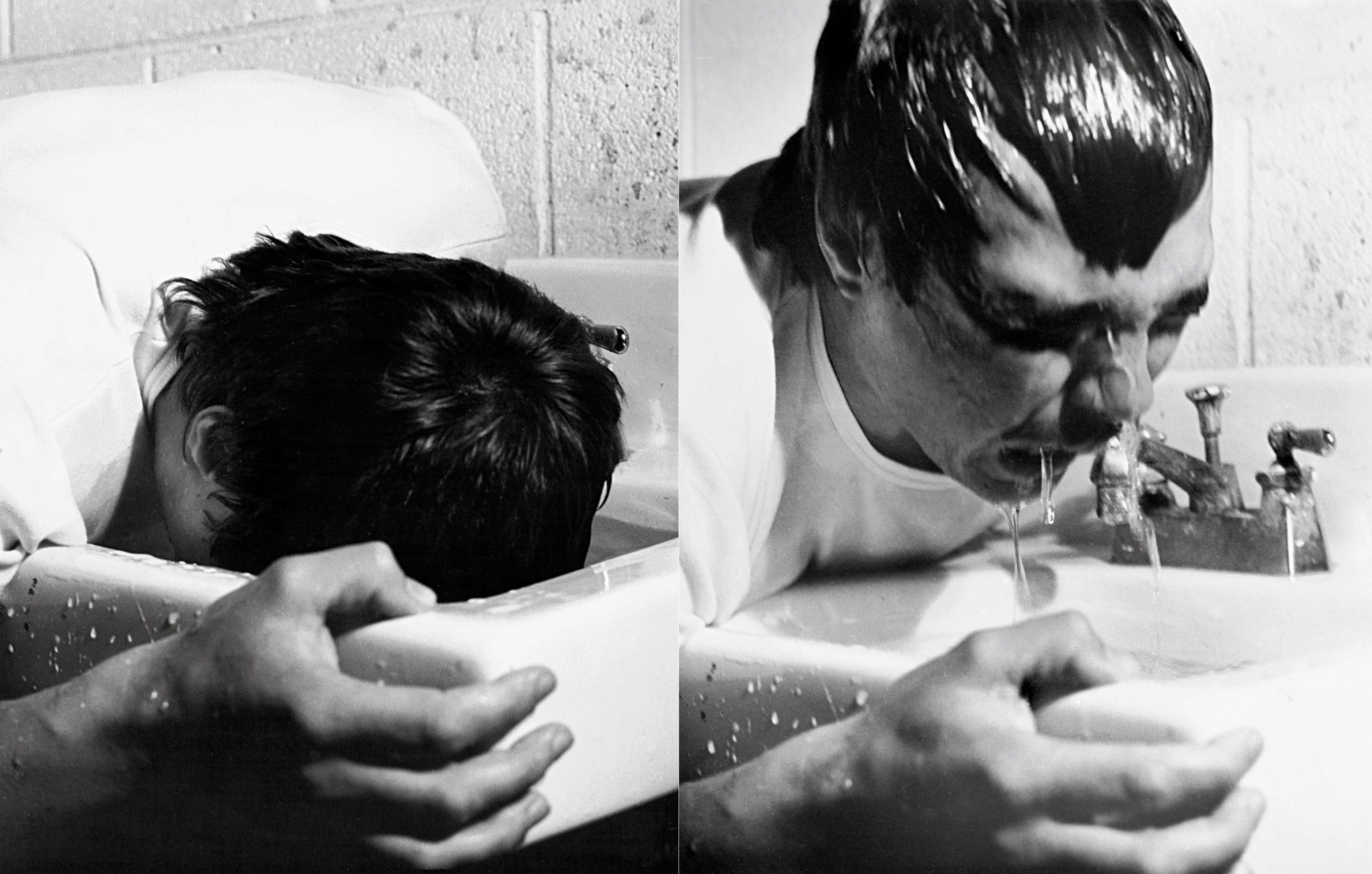

If Burden’s television commercials represent an attempt to disrupt the hypnosis of TV, to introduce a moment of intellectual confusion or conflict into its steady stream of consumerist-patriotic, normative-values pandering, Burden’s performances Velvet Water and Do You Believe in Television show how in his experiential work, he was positioning the construct of watching as a conditioned response to the presence of a turned-on television monitor. In Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, Mander’s stance is essentially anti-image: that text, memory, and the daily improvisation of living require flexibility and analysis, but television trains humans to allow images to bypass consciousness. Summarizing his argument in a concluding chapter with the evocative title “Impossible Thoughts,” Mander writes, “Television suppresses and replaces creative human imagery, encourages mental passivity, and trains people to accept authority.”14Burden’s 1974 performance Velvet Water at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago seemed designed to test exactly this.15A crowded audience sat in a small room facing a stage empty but for a 19-inch TV monitor framed on its horizontal sides by four smaller monitors. The imagery on each of the monitors was of Burden in real time. Burden was in fact very close by, but was on the other side of a row of cabinets, out of sight from the audience. As seen on the screens, Burden—not more than 20 feet away—stood near a sink filled with water. The large monitor transmitted a live close-up shot of his face to the audience, while the smaller monitors broadcast a longer-distance live shot of Burden’s torso, head, and the sink. After announcing, “Today I am going to breathe water, which is the opposite of drowning, because when you breathe water you believe water to be a richer, thicker oxygen capable of sustaining life,” Burden plunged his face into the sink.16He occasionally gasped for air before submerging his head again. After five minutes of this he collapsed, choking.

Chris Burden, stills from Velvet Water, 1974. Photo: Alan Leder. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery, © Chris Burden.

Velvet Water feels like the culmination of a thread that began with Shoot. That performance actualized the sensationalistic stuff of TV dramas and the nightly news. But aside from its sociopolitical connotations, it contained heroic connotations of Burden as lone survivor. He was very much the performance’s sole subject. Velvet Water retains the vivid political suggestiveness that spikes many of Burden’s best performances. His auto-torture is evocatively similar to how the French police torture the Algerian sympathizer Bruno Forestier in Godard’s Le Petit Soldat (1963), not to mention any number of modern waterboarding videos, but I would argue that the audience—not Burden—was the unwitting subject of the performance.17Burden had by this point established a reputation for being a careful, responsible coordinator of his own performances. He must have known that nobody would interrupt him. But he was also clearly choking, and was probably close enough to the spectators that his gasps were audible not only from the television monitor but also in real time, from the adjacent room. Unlike in Do You Believe in Television, where his physical presence was only implied, those present at Velvet Water knew he was right there with them. They were set up as examples of conditioned passivity in the presence of a television set. As Robert Horvitz wrote of the work, in Artforum in 1976, “The electronic link between him and the audience tacitly implicated them in this ordeal, even as it seemed to distance them sensually.”18Burden—onscreen and thus invincible—was demonstrating television’s force field of inaction.

By 1976, Burden’s preoccupation with television art was in full swing. The most literal situation he staged to test television as metaphor for belief was on February 26 at the Alberta College of Art in Calgary. Prior to the performance Do You Believe in Television, Burden scattered a trail of hay that began in the basement of the building and continued up three flights of stairs. Large TV monitors were mounted on the landings of each floor where those in attendance were expected to gather. The monitors showed a video image of a black cross on the floor, made with what appeared to be paint. The cross, visible nowhere in the space except on the monitors, was surrounded with hay, the only reference to the hay the spectators would have been walking on during the anxious moments when nobody knew exactly what would happen. Suddenly a loud voice emanating from the monitors asked, “Do you believe in television?” and the video screens showed a hand lighting the hay with a match. A flame then shot up from the basement riding the path of hay toward the audience on the stairs above. The live fire made it somewhere near the building’s second level before the spectators—understanding that complicity could equal disaster—pounced on the flame to extinguish it.

Burden was simply asking those present at these two performances to connect what they saw on a screen to what was happening in real life, but it was an unnatural request; television’s success depends on viewer disassociation from reality, or rather television’s ability to create an alternative version of reality. An executive autocracy controls which images appear on television, so its viewers aren’t naturalizing and emulating reality; they’re emulating the fictions and fantasies endorsed by the media ruling class. Dieter Daniels, in his essay “Television—Art or Anti Art?” wrote, “All of Burden’s television actions stand as appropriations of the reality of the medium, but at the same time show that no artist is in a position to compete seriously with the industrial production of television as a technique, program and institution.”19 Even today, this is absolutely accurate. But it obscures the possibility that Burden never intended to compete with television; he used it to reveal something about its effects on communicative potentiality, namely that it sanctioned voyeurism, passiveness, and deference to the logic of authority. Did he succeed? Is “success” possible or quantifiable in a nation so beholden to corporate interests, where the national addiction to technological gadgets has reached the point where the day after Apple’s iPad was released a vacationing family “Didn’t go out to dinner … We just sat there on our devices”?20Burden’s work didn’t have the activist aspirations of, say, the Raindance Corporation and other collectives in the early 1970s. Those groups sought to enable people to make their own TV, and believed that by doing so they would give them the necessary intellectual tools to deconstruct it and combat its domination and inhabitation of the human imagination. But by situating the television set and by using the commercial form as implicit vessels of authority, Burden’s work about how television influences behavior asked the most penetrating and ethical question of any artist I can think of who used the medium: Do you believe in television?