Don Bachardy: Regarding Portraits

by Susan Morgan

Don Bachardy, Shahin, 2005. Acrylic on paper, 22 x 29 in. Courtesy of the artist and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica.

Artist Don Bachardy, who was born in Los Angeles in 1934, has remarked that LA was the best place to live because it’s where movies are made. During World War II, while his father worked swing shift at Lockheed Aircraft, Bachardy and his older brother slipped away with their mother to downtown movie palaces, escaping into a shared enchantment with the silver screen. By the time he was five, recalls Bachardy, movies had become an obsession. “I’m convinced,” he wrote in 2000, “that my interest in looking at people came directly from gazing, when I was very young and impressionable, at close-ups of movie actors several hundred times larger than life.”1

Bachardy has now been making portraits from life for more than fifty years. As a writer, I’ve often regarded my own work—composing profiles, researching biographies, collecting interviews—as a type of portraiture. I look hard and openly at my subjects in order to unearth genuinely telling details and subtle indicators, compelling qualities that can be translated into language and fixed to the page. Although I’ve written about portraiture and artists ranging from Edward Weston to Catherine Opie, I’ve always shied away from being a subject myself. I’d rather observe than be seen. Over the years, however, I’ve thought a lot about what occurs between a gifted portraitist and a carefully considered subject, that tricky blending of absolute vigilance and guileless improvisation. In 2006, Elaine Dundy introduced me to Don Bachardy. Dundy, who died in 2008, was an ebullient octogenarian author best known for her 1958 novel The Dud Avocado, a girl’s own picaresque, a Parisian screwball comedy that Gore Vidal referred to as “Daisy Miller’s Revenge.” “You must meet Don,” Elaine had insisted, so I did.

When we first met, Bachardy asked if I would sit for him (since, as he is quick to point out, he asks just about everyone). I reckoned that it was about time to test the subject side of my portraiture ideas, so I agreed. Bachardy completes each portrait in a single sitting. “It’s like a spell that is broken when my sitter leaves,” he told one interviewer. “I don’t trust myself to add or detract from the work I’ve done.” I’ve now sat for him several times, and the experience is always extraordinary, a surprising marriage of meditation and collaborative performance; my ideas about portraiture have been confirmed and expanded. Bachardy’s work is vibrant and attentive, a remarkable display of visual acumen and essential kinesthetic knowledge. Sharply observed and powerfully realized, his portraits record human faces while capturing transitory experience and the ineffable sensation of looking deeply.

In 2007, Bachardy’s own life appeared as a movie: the documentary film Chris and Don: A Love Story chronicled his 34-year relationship with the British expatriate writer Christopher Isherwood.2When the two first met on a Santa Monica beach in 1952, Bachardy was an 18-year-old UCLA student and Isherwood was a 48-year-old novelist with a well-established literary reputation and Hollywood screenwriting credentials. They remained together until Isherwood’s death, in 1986. Last year, Bachardy could be glimpsed delivering a one-line cameo role in A Single Man (2009), Tom Ford’s incisive, heartbreaking and stylish directorial debut based on Isherwood’s 1964 novel of the same name. Bachardy had provided the book’s title, and the plot was, in part, inspired by a brief rupture in the couple’s relationship. As the beguilingly quick-witted artist informed one interviewer: “The period before he started working on the book was the bumpiest in our relationship, when it seemed more possible than ever before or after that we really might split up. Chris was very concerned and began imagining what he might do, how he would cope with his life. So he kills off my character in an automobile accident.”3

Bachardy works in a simple two-story studio, a beautiful bright white box awash with northern light, perched on the edge of a canyon and looking out over the great expanse of ocean. It’s a location instantly familiar to readers of A Single Man, in which the scenes are set within hill-hugging houses and populous ravines criss-crossed by wooden staircases. In the film, however, Los Angeles spreads out more typically—modern, sprawling, and almost endlessly horizontal. Among the other alterations that occurred in the translation from page to screen were changes to the character Charley, the female friend of the story’s protagonist, George. “I wrote Charley in a more glamorous way, with a past history with George,” Tom Ford has explained. “I asked Don about that, and he said, ‘It’s really funny that you did that. The original Charley was based on Iris Tree.4She was really glamorous, very much like the character that you have written, but Christopher didn’t want her to know that she was the basis for that character so he had dramatically changed her in the book.’ ”5In the novel, when George and Charley meet for a cocktail-fueled supper and a bungled heart-to-heart, Charley serves up a stew, a new recipe culled from a travel book about Borneo. For this initial East of Borneo interview, it adds an odd and surprising echo as Don Bachardy describes how his studio practice and portraiture habit developed.

Don Bachardy: I began asking my friends to sit for me when I was still in Chouinard Art Institute. Iris Tree was a very early sitter. Igor Stravinsky was one of my very first sitters because he adored Chris.6Vera [Stravinsky] also sat for me several times. She was just gorgeous and such a lovable creature—a lush face and so funny and charming. I adored her. She and Bob set it up for Igor.7I did four drawings of him one evening after dinner. You can imagine how I was trembling. We went into his little study, the inner sanctum, and he just stretched out on a sofa. Then, he sat in a chair for the next three. I did four and they were all like him and not bad at all. It was really one of my earliest triumphs because everybody was pleased. He approved of the drawings. Vera and Bob liked them and Chris, of course, was so excited at my success.

Susan Morgan: A success despite your trembling.

DB: I’d gone through dinner with just one drink, wondering how I was going to manage. Stravinsky had a fierce reputation. He was so rude to most people, but if you really got into the house and they decided they liked you, they couldn’t have been more charming.

SM: Once you began to work with a sitter, how were you able to establish your regular studio rhythm?

DB: It really began in 1956 when I was going to Chouinard. I would be there from nine until four, five days a week. And often, I went back from seven to nine. I wasn’t studying for any kind of certificate so I took any of the classes that had live models. I knew that it was all or nothing: either I was going to be an artist or not. I’d signed up for a six-week summer course and the very first week, I got hooked on the life drawing. On Friday, I knew I had found my vocation. I quit UCLA and signed up for the fall term. I went continually and on the nights when I wasn’t at Chouinard, I was often at Art Center College of Design or Otis or UCLA Extension—wherever they had uninstructed drawing classes. I’d been pent up for so long and suddenly, when I realized my vocation, I just couldn’t get enough of it. My early drawing experience had been minutely copying photographs in magazines. None of those drawings were interesting but doing them had sharpened my eye. And when I applied that to a live model, it was just so exhilarating for me.

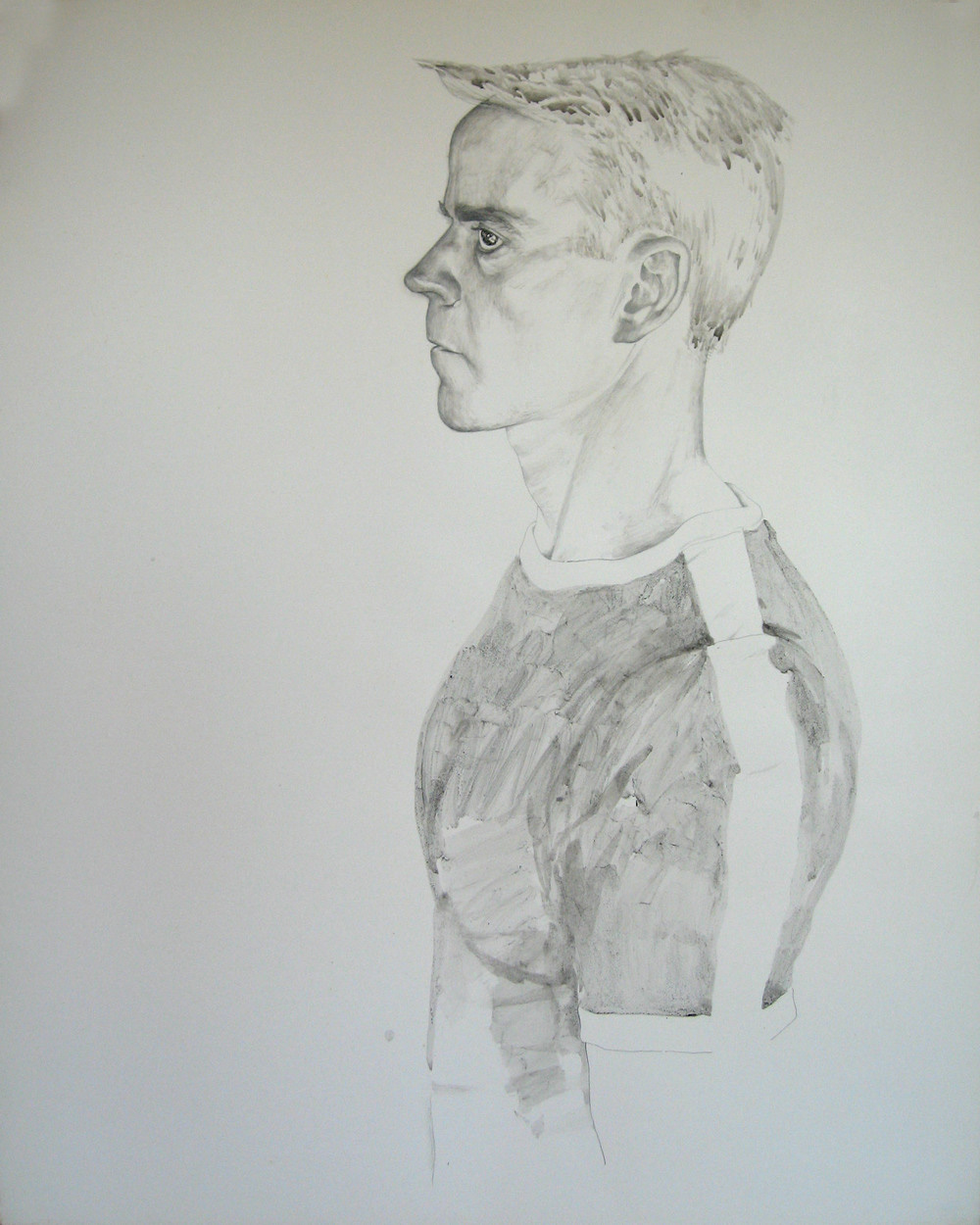

Self-portrait, 1976. Pencil and ink wash on paper. 24 x 19 in. Courtesy of the artist and Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica.

SM: What was the atmosphere like for you as a young artist working figuratively in the mid-1950s?

DB: I was like an explorer; nobody else was doing it. I felt totally eccentric, so out of the swim. Abstract expressionism was raging and here I was—doing pictures of people and feeling embarrassed about it. That’s why I didn’t really have any artist friends for years; I thought they would consider me too far out, too behind the times. When I finally got to know artist friends, I didn’t really understand what a distinction being able to draw gave me among them. In ’61, I went to England to study at the Slade School of Fine Art. But the Slade was just more school and I was already weary of that so I just started asking everybody I met if they would sit for me. Through Chris, I’d met people like John Gielgud and Freddy Ashton, actors, dancers, composers.8 And because I was young and energetic and nice looking, it was easy. They were charming to me. After six months there, I had a portfolio of work. A friend knew somebody at the Redfern Gallery and set up a meeting for me; I took my portfolio and they offered me a show on the spot. And it was a big success. It wasn’t the key show, it was the downstairs room, but every inch of the walls was covered with the work I’d been doing: drawings of E. M. Forster and Auden that I sold for 25 pounds, drawings that I would never be able to do again. And I was thrilled to sell them for 25 pounds. I would just kill to have one of those drawings of Forster back. But nobody told me, “Don’t sell these drawings. You’ll never be able to do most of these people again.” But then, I wouldn’t have believed them anyway.

SM: But you were having your first show, entering into the world you desired, participating and being acknowledged.

DB: And that was the beginning. I even got into the newspapers. The reviews were condescending, but I didn’t care. I was in the newspaper and I got lots and lots of commissions. It took me another six months to do all the work. In a way, I’ve never had as successful a show after that. I sold all those pictures out of the show and I got all kinds of commissions. I was launched. And I was 27.

SM: And then you came back to Santa Monica Canyon. Hadn’t you moved into this house in ’59?

DB: Yes and imagine, I drove every day to Chouinard, way downtown by MacArthur Park. Of course, the traffic was heavy but nothing like now. It would be unthinkable now. In the old days, I could do it under half an hour.

SM: Were you able to set up a studio and a schedule at home?

DB: This property was the first time I had a studio. It took a couple of years but we turned the garage into a studio—we had a bathroom and a sink put in and sliding glass doors so I had light. It was just one little room but it was a genuine studio and the first time that I had a place to invite people to come and sit for me. In those early years, when I would ask people to sit, I used to go to them. I worked under unthinkable conditions. You know, how a lot of people live in dark holes. And I didn’t even have a drawing bench. I used to lug around that [drawing] horse from Chouinard. Or I would set up two dining room chairs without arms. I’d sit on one and face the other one toward me and prop my board on the back. If the dining room chairs wouldn’t work, I would sit on a straight-back chair and back another up to me and prop my board on my knees. I was just determined, so I made it work one way or another. And then, so many people didn’t know how to sit, what was expected of them. I got all kinds of odd responses and I was still shy enough that I thought it was rude to ask somebody to sit still. [Laughs] You know, just getting in the front door, if it was a famous Hollywood actor, was an achievement. All the more terrifying to even consider the prospect of confronting them.

SM: While you were an itinerant portraitist, did you always keep a drawing board in the car?

DB: I always had the board in the car. I used a cameraman’s shoulder bag and a couple of the movie people froze when I appeared with this shoulder bag. “I thought you were going to draw! That’s a camera, isn’t it?” Thinking I was going to catch them without warning with my camera. And I’d say “No, no, no.” the shoulder bag was just the right size for my easel and pencils and pen.

SM: When did you first show your work in LA?

DB: I had my first show in ’62 at Rex Evans’s Gallery on La Cienega.9The space is still there, I think a decorator has it. There’s a walk of shops, just north of Melrose Place, leading to a two-story building and Rex and his friend Jim Weatherford had the gallery on the second floor there.

SM: Wasn’t Rex Evans also an actor?

DB: He was an actor who shows up in a lot of movies. You see him a lot in Greta Garbo’s Camille, he plays one of her friends. He was very fat and jolly and a good friend of George Cukor.

SM: For your first exhibition there, did you show Hollywood portraits?

DB: I showed Hollywood portraits and also writers—I’d made a specialty of that and I was really tireless. For years I chased after people. I really really did my boot camp experience. When I came back from my London success, I did what I had learned to do—asking everybody I met to sit for me. I had amazing luck in getting people to agree. Well, of course being with Chris—that gave me a guarantee, a credential. They knew he wasn’t kidding, he was distinguished in his own right. And so they allowed it.

Joan Didion, 1972. Ink and pencil on paper. 29 x 23 in. Courtesy of the artist.

SM: Didn’t he also ask people for you?

DB: He did ask people, or we would go to parties together and I would meet my quarry. With him beside me, I could dare to ask whomever—would he or she sit for me. I think the whole attitude now in Hollywood is different, I don’t think I could probably manage so successfully that kind of attack. Even with Chris in hand. It just seems—maybe it’s just that I’m so much older now—but it seems a totally different setup. People have people. They’re inventing themselves by everything being an obstacle. They think that it gives them a license for their job. They imagine that’s what justifies them. In those days, even major movie stars didn’t have publicity people or managers.

SM: Did that unguarded aspect make life a bit more interesting—the possibility that you might unexpectedly encounter someone?

DB: It was so much more interesting. You could go to a celebrity gathering and there might not be any photographers. Now there are photographers and police and security just going to a party. It’s a very different world.

SM: You’ve always worked so consistently in the studio—nearly every day for fifty years. Did you and Chris share the same work habits?

DB: We encouraged each other. It was an ideal setup—we worked at opposite ends of the property. We would always begin the day together, have breakfast together and talk, and then, at a certain point we would separate and work. Sometimes, we’d meet in the middle of the day but usually I would go out to the studio in the morning and not come back to the house until late afternoon or early evening. I knew he was working, he knew I was working, and we both agreed that was psychologically helpful.

SM: Did you know any other artists who worked like that?

DB: Another pair, another couple? No, I think it was rare then, particularly with queer couples. There was usually one dominantly successful one and the other became more an acolyte of some sort, more of a shadow person.

SM: I think the last time we spoke, you’d just been up to San Francisco for a Theophilus Brown show. Since he and Paul Wonner are so strongly identified as Bay Area painters, I hadn’t realized that they’d lived in Santa Monica for a while during the ’60s.

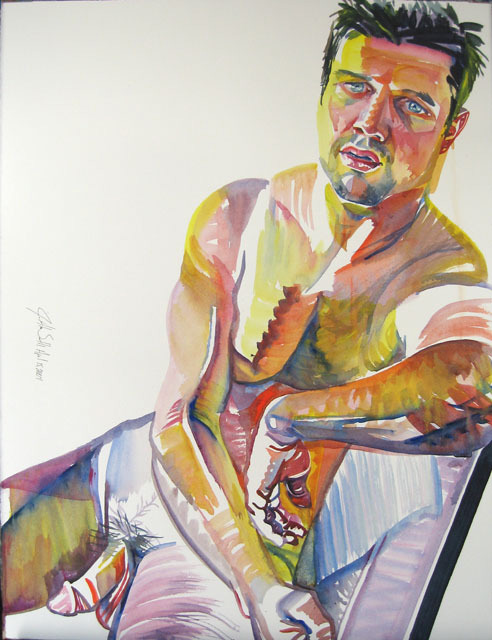

J. Smith, 2004. Acrylic on paper. 29 1/2 x 22 in. Courtesy of the Craig Krull Gallery, Santa Monica.

DB: They had an apartment right here on 3rd Street in ’63 and ’64. Now, that’s a very good example. They were pretty much a pair but Bill [William Theophilus Brown] always bowed to Paul. Bill behaved as though Paul were the real painter and he was the dabbler. But, of course, he was perfectly serious and he’s never stopped painting and he’s good, but there was something about having been raised a rich boy that made Bill modest about his talents. I also sincerely believe that he believed that Paul was his superior as an artist. And I think tacitly Paul accepted that too. [laughs]

We used to meet one evening a week, either at their apartment or here, and hire a model or find a friend who would sit for us. We worked together a lot. When Cecil Beaton was working on My Fair Lady, he sometimes came to our drawing sessions. And drew.

We’d met Bill and Paul through our closest heterosexual friends, Jo Lathwood, who was a clothing designer, and Ben Masselink, who was a struggling writer. Chris was very encouraging to him. Jo was about twenty years older than Ben, so there was some identification going on; they were sort of a heterosexual version of us.

Chris, you see, was so smart. He encouraged me to be an artist because he saw I had a real flair for it. He also believed that I had some talent for writing, but he didn’t encourage that like he did the art because he knew that two people who lived together and practiced the same art were more likely to have trouble—to be competitive, to have one be more successful than the other. Being in different fields was much safer. And he was very savvy in that.