End of the End of the End: Agnès Varda in Los Angeles

by Sasha Archibald

Agnès Varda (center) with Viva on the set of Lions Love (…and Lies), 1969. Courtesy Mary Evans/Ronald Grant/Everett Collection.

Cultural elites have long treasured Hollywood as the butt of their jokes. Hollywood is a reviled yet useful counterpoint—the distaste to taste, the crass to high-mindedness, “the antipode to critical intelligence.”1 Nonetheless, almost from its inception, the film industry has scooped talent from theater, literature, dance, and visual arts—tapping the very sorts of cultural workers that disdain it most. Enticed by piles of money and sunshine postcards, artists have arrived in Los Angeles in droves. Often with misgivings and often against their better judgment, and yet they arrived. Few could afford to ignore Hollywood’s oily handshake.

The usual strategy for keeping a sense of dignity while still cashing in on the spoils of corporate film was to bite the hand that wrote the paycheck. William Faulkner, for instance, posed as a recalcitrant child, swearing to his employer, MGM, that the only movies he’d seen were newsreels and Mickey Mouse cartoons. He famously greeted Clark Gable at a party by inquiring, “Mr. Gable, what do you do?” Dorothy Parker declared all of Hollywood asinine but happily spent her outrageous income—$100,000 a year during the height of the Great Depression—on exquisite lingerie and perfume. F. Scott Fitzgerald and Bertolt Brecht both avidly pursued Hollywood deals, only to castigate themselves as hacks. Brecht had the usual epithets for the industry—“marketplace of lies,” “world center of the narcotics trade”—but more poignant are the poems he jotted in his journals, allegedly composed of real quotes from industry brokers, to which Brecht added his own miserable postscript:

Show yourself as one of us, we

Will call you The Best,

We can pay, we have the means

No one besides us can

Deliver the goodsKnow this: our big shows

Show what we want to have shown.

Play our game, we divide the loot.

Deliver the goods, be honest with us.When I see their rotting faces

My hunger goes away.2

Some writers tolerated Hollywood for decades, some lasted only a few months, and some came and went as their psyches permitted or pocketbooks demanded. After years of painful ambivalence and alcoholic binges, Faulkner begged to be released from his contract, citing emotional distress. The pay was adequate, the arrangement flexible, his colleagues pleasant—yet, he wrote, “I have had about all of Hollywood I can stand. I feel bad, depressed, [a] dreadful sense of wasting time. I imagine most of the symptoms of blow-up or collapse. […] I am actually afraid to stay here much longer.”3 MGM eventually consented, and Faulkner fled to Mississippi. He was back though, eight years later. He’d won a Nobel Prize in the interim, but Hollywood money talked.

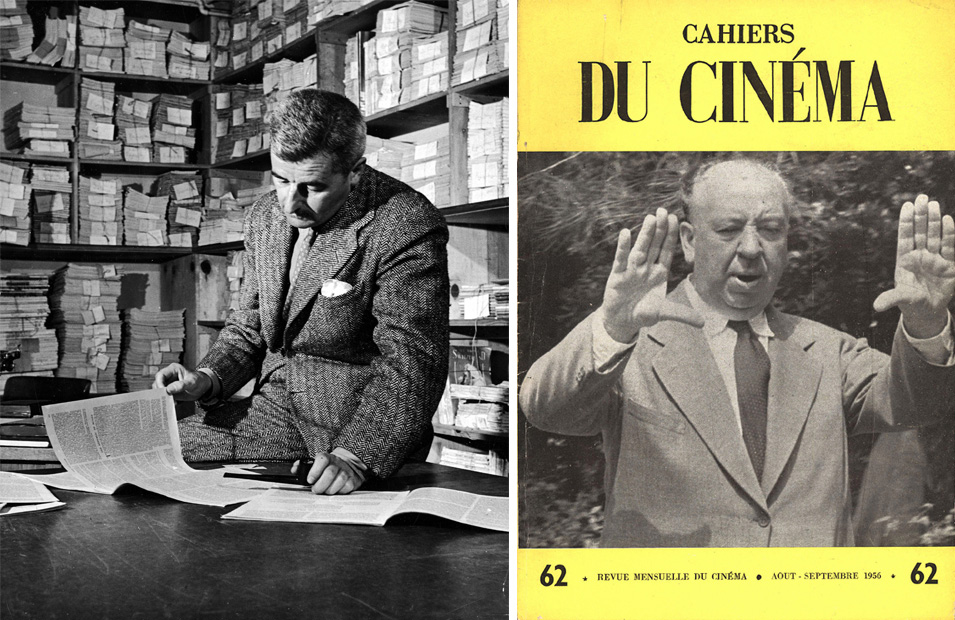

Left: American author William Faulkner reads through documents in the Warner Bros.’ research department as possible script material, Hollywood, California, 1942. Courtesy Alfred Eriss/Pix Inc./Time Life Pictures/Getty Images. Right: Alfred Hitchcock on the cover of Cahiers du Cinéma no. 62 (August-September 1956).

The antipathy between Hollywood and cultural elites began to erode in the 1960s, due in part to the birth of the French new wave. Hollywood film flooded French theaters in the immediate postwar years: During the first six months of 1946, 38 American films were shown in France, and during the first six months of 1947, 338 films were shown. The deluge, which included such classics as Casablanca (1942), Citizen Kane (1941), and The Wizard of Oz (1939), demanded a response. Forced to define their position on American cinema, French intellectuals chose nuanced critique rather than blanket dismissal, singling out a few Hollywood directors that deserved cultural cachet. Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, and Billy Wilder, for instance, were admired by the editors of Cahiers du Cinéma, the French film journal founded in 1951, while a rival publication, Positif, touted the virtues of John Huston and Orson Welles. These and other film magazines legitimized cinema with medium-specific discourse, while ciné-clubs like Objectif 49 and Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin analyzed films in detail, ultimately dignifying film spectatorship as something more than mindless leisure. Hollywood saw its good fortune in this Francophile turn. Cahiers du Cinéma improbably became essential reading, and Fritz Lang and others began to pose for photographs clutching the latest issue.4 Eventually, studio management joined the trend, counting French auteur filmmakers such as Agnès Varda and her husband, Jacques Demy, among their recruits.

Columbia approached Demy first, a logical choice. Despite his affiliation with the new wave, Hollywood was Demy’s stylistic touchstone. His films are riotous spectacles of color and song in the American musical tradition—films that pay homage, even as they deepen and complicate the genre. In fact, long before he arrived in California, it was said that Demy’s films “smell[ed]” of Hollywood.5 (By the same token, the work was also described as “fruity.”)6 Hollywood was also the only place where singing-dancing extravaganzas were amply funded. George Beauregard, the French producer of many new wave classics, liked Demy’s ideas but balked at the price tag. When Demy approached him with the script for a filmic opera in which every line is sung and every backdrop wallpapered in an eye-popping pattern, Beauregard suggested it be shot in black and white, with no costumes and no music. Demy demurred and made his film instead with the producer Mag Bodard. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) went on to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes and five Academy Award nominations. With his film’s international success, Demy was a breath away from Hollywood.

Varda later explained what anyone who knew Demy’s work would have already understood—that the Hollywood deal was fait accompli: “When Jacques was 15 years old he wanted to get an American car. And he wanted to come to Hollywood to make a movie, and I followed.”7 In fact, Varda was not in the habit of following Demy. They had met at the Festival of Tours in 1958, two promising filmmakers at the start of their careers—Varda was in addition a single mother—and sustained a marriage generous enough to accommodate two singular visions. Neither partner, it seems, was martyred to the other’s ambition. Yet, though Demy asked little of Varda in terms of wifely duties, having arrived in Los Angeles to begin work with Columbia Pictures—the project would become Model Shop (1969)—he telephoned and requested her company for the months to come. She complied, and they rented a house in 1966.

Varda (right) with Jacques Demy and Anouk Aimée on set of Model Shop, 1969. Courtesy Ciné-Tamaris.

Once the family settled, the Columbia executive who brokered the contract with Demy, George Ayres, then pursued Varda, commissioning from her a manuscript about American hippies, Peace and Love. Columbia liked the script, but negotiations ended abruptly and the film was never made. Ayres (who also approached Andy Warhol) teases that Varda walked away because an executive pinched her cheek; Varda claims Columbia wouldn’t promise her final cut, and signing on without it was unthinkable. The incident is a minor detail in Varda hagiography, and yet it launched her extended engagement with Los Angeles, a relationship between city and filmmaker that would eventually include two sojourns and five films, all conceived, written, filmed, and edited in California. Of the five, two were shorts—Uncle Yanco (1967) and Huey (1968)—shot respectively in Marin County and Oakland, while the three features, Lions Love (…and Lies) (1969), Documenteur: An Emotion Picture (1981), and Mur Murs (1981), are Los Angeles films inside and out, indelibly marked by Varda’s experience of the city.8

By the time of her first visit to Los Angeles in 1967, Varda was already an accomplished filmmaker, having directed four features in France, including the celebrated Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), a day in the life of a famous singer as she awaits the results of a life-or-death medical test. Her first film, La Pointe Courte, made in 1954, created even more of a stir, at least within a small and influential circle of burgeoning filmmakers. La Pointe Courte is now credited as heralding the arrival of a new movement in film and Varda’s name inextricably attached to the moniker “grandmother of the French new wave.” The compliment carries a whiff of condescension; the age difference between Varda and Jean-Luc Godard or François Truffaut is not a generation but less than five years, and it is premature to assign Varda—who, at 85, continues to make films, teach, travel widely, and speak sharply—her epitaph. It is, however, to the point: Varda’s innovative formal structure and use of natural light and nonprofessional actors in La Pointe Courte predated the earliest work of any of her contemporaries.

Varda (center) on the set of Cléo de 5 à 7 (Cleo from 5 to 7), 1962.

Initially at least, Varda influenced film as an outsider. When she made La Pointe Courte, she was entirely self-taught and a film naïf. “I seemed to be there by mistake,” she later remembered of her first meeting with the new wave cadre—Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer, Jacques Rivette, Truffaut, Godard, and others—“feeling small, ignorant, and the only woman.”9 Her miasma was unwarranted, as she was the only one of the group to have actually made a film. Her would-be peers were critics and cinephiles first, filmmakers second, while Varda’s background was in art history and her interest in literature. She wasn’t watching films in her early twenties but attending classes by philosopher Gaston Bachelard at the Sorbonne and aspiring to be a museum curator, photographing children on the laps of Santa Claus and dancers for the People’s National Theater. Her touchstone as a filmmaker was not Jean Renoir or Orson Welles, whom she claimed to have never heard of, but the formal strategy of Faulkner’s Wild Palms (1939), a novel told on two discordant tracks that she devoured, dissected, marveled at, and finally decided to try on film.

Like all travelers, Varda brought to Los Angeles a suitcase of assumptions and judgments. In the late 1960s, America in general—and California in particular—seemed to many foreign observers a cesspool of violence and imperialism. America’s war in Vietnam, racist cops, and brutal attempts to contain civil unrest were international news. Los Angeles’s reputation abroad was specifically haunted by the 1965 Watts riot. American leftists found little redeeming in the violence, but in Paris, Guy Debord of the Situationist International circulated an essay describing the tragedy as a “rebellion against the commodity.”10 Varda may or may not have known Debord’s work—more likely the former, since he had unfavorably reviewed her films—but she generally shared the politics of her milieu.11 She was openly disgusted by American racism and, like many white European intellectuals (most famously Jean Genet), strongly identified with the Black Panthers. In fact, one of her major coups in California was a commission from French television to shoot a documentary short about the Black Panthers, including a coveted interview with Huey Newton in jail. Varda’s depiction of the Panthers is unusually fair-minded, portraying protests in downtown Oakland as congenial family gatherings.12 Varda’s disgust with mainstream American culture is more transparently obvious in a 1969 discussion with Newsweek editor Jack Kroll, conducted at the New York Film Festival and later televised. Twice, Kroll describes the filmic subjects in the first of Varda’s Los Angeles films, Lions Love (…and Lies), as “grotesque,” and twice Varda recoils. Finally, brimming with disdain, she interrupts to tell Kroll his is a “racist position”—racist in this case summing up all variety of American stupidity.13

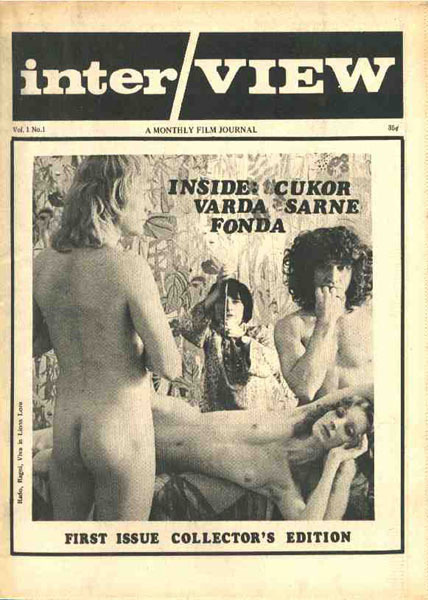

Varda and Lions Love featured on the cover of Interview magazine, issue 1.

In fact, Varda’s California films are devoted to such “grotesque” characters, the marginalized and denigrated types that make of California a hypertrophic variation on America. Varda found in Los Angeles a city of seekers—explorers, refugees, and desperadoes who had pushed westward and westward again, compelled by nothing but dreams, and finally arriving at the edge of a continent. The search that has no object resonated with Varda; she is, by her own admission, a gleaner for whom searching and living are coincident. The natural terminus of such a search—the beach—was where Varda felt most at home. The edge of the sea is both a symbol of dramatic finality and endless expansion, and what happens there is one of Varda’s great themes.14 How to live on a precipice? Having pushed westward until there is no more West, what sorts of searches remain?

Thom Andersen argues in his documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) that Hollywood is the pervasive source of mistruths about Los Angeles. Hollywood habitually maligns its home, making of Los Angeles a city that is salacious, trivial, corrupt, and disposable. Varda’s first Los Angeles film radically reverses this pattern; Lions Love (…and Lies) represents Hollywood from the perspective of consummate outsiders. As Varda tells it, it is Hollywood, not Los Angeles, that is vain and morally bankrupt. The plot of the film undoubtedly references Varda’s own Hollywood experience. Filmmaker Shirley Clarke, playing herself as an avatar of Varda, is bid by the studios to make a movie, and the film opens with Clarke arriving in Los Angeles from New York to discuss the matter in person. During a series of meetings with white men in business suits, Clarke sits mutely as the men refer to her as “gal” (Varda herself was then 39), admit they haven’t seen her previous films, and ultimately demand their right to make a profit, artistic integrity be damned. The Columbia executive, Max, appears to be played by Max Factor Jr., the president of the eponymous makeup line—an inside wink, no doubt, to the superficiality of the entire enterprise. (In a similar aside, the film dialogue confuses decorator with director.) At the end of the negotiations, in an obvious parody of Hollywood’s narcissism, Clarke tries to kill herself with sleeping pills. At this point in the film, Clarke breaks character to protest—“I would never kill myself this way!” she complains. Varda irritably insists, leaving her director chair to demonstrate. The camera keeps running, a breach in film etiquette that denudes this film, or any other, of any claim on reality. Hollywood, Varda points out, is allowed to define the stakes of Hollywood success; only in the movies does a dead-end movie deal warrant suicide.

Agnès Varda, Lion Love (…and Lies), 1969 (still). Color film in 35mm, 110 min. Courtesy Ciné-Tamaris.

Clarke’s suicide attempt takes place at her friends’ tacky rental, the setting for most of the action in Lions Love (…and Lies). The focus of the film is actually not Clarke’s adventures in Hollywood but her bohemian Los Angeles hosts: the chaste ménage à trois of Viva—the haughty debauched intellectual of Warhol’s Blue Movie aka Fuck (1969) and several other Warhol films—alongside Jerome Ragni and James Rado, creators and stars of the 1968 musical Hair. Naked and nuzzling, the three are languorous in their movements and arch in their speech, each sporting an unruly mane of hair. They play dress-up, read aloud, and lounge by the kidney-shaped pool, feigning vacuity. Varda initially seems interested in Viva, Ragni, and Rado’s stylized identity performance, an act that moves seamlessly from stage to screen to living room and that Varda recognizes as forever undoing the distinction between real people and actors. But she doesn’t hew closely to this theme—it’s all rote at this point anyway—and instead indulges her fascination-repulsion with the detritus of American consumerism, particularly objects that seem like paragons of inauthenticity: wallpaper printed to look like trees, clothes printed to look like flags, plastic flowers, plastic fruit, French fries. (Indeed, Varda once described the movie as an “inventory.”)15 Clarke’s welcome tour sums up the muddled relationship between artifice, reality, and Hollywood: “[Here is] a genuine plastic weeping willow,” her hosts gesture. “There’s a real one out there, but it belongs to Katharine Hepburn.”

Varda’s insouciance to Hollywood had scarcely diminished 13 years later, in 1980, when she was again approached by the studios to submit a script. Showing little concern for what was likely to be produced, she wrote a story based on a real Los Angeles event she’d read about in the Paris newspapers. A man was walking down the street naked at 5 a.m. He lived nearby, and his pregnant wife was home asleep. Strolling along on the sidewalk, he encountered an LAPD police officer who shot and killed him. When the officer was questioned why, he simply said, according to Varda’s telling of the story, “Because of his eyes.”16 Her script related the incident through the perspective of a French woman who happened to witness the murder from her window.

As Varda might have guessed, Hollywood refused to produce a film about a police officer’s poor judgment, and the same sequence of events repeated itself. When the script was a dead end and the deal came to naught, Varda chose to remain in Los Angeles to independently produce two more features: Documenteur: An Emotion Picture, about a single mother struggling to make a home, and Mur Murs, a documentary about murals and their creators. Varda conceived of the two films as twins and originally screened them together, though they were later separated when she decided each was stronger on its own.

They are very different films. The charms of Mur Murs are straightforward—the verve of claiming a public wall, footage of vintage Los Angeles—while Documenteur is often inscrutable. It’s the latter film that Varda herself prefers; she describes Documenteur as both her saddest film and her favorite. As the subtitle suggests, her subject is as much emotional vicissitudes in general as it is the plight of Emilie and Martin, played by Varda’s editor Sabine Mamou and Varda’s own son, eight-year-old Mathieu Demy. Emilie and Martin are striking out to live on their own, leaving behind the lover-father that completes their family. The separation has set mother and son adrift in a sea of melancholy.

Agnès Varda, Documenteur: An Emotion Picture, 1981 (still). Color film in 16mm, 63 min. Courtesy Ciné-Tamaris.

Varda evokes Emilie’s and Martin’s despondency by sinking the film in wet shadows. Although Documenteur was entirely shot in Los Angeles, it is strewn with puddles and sweaters. The palm trees are familiar, but in Documenteur they forebodingly sway, while the muted palate, status quo in Seattle or London, is in Los Angeles dystopic and unsettling. Varda spoke recently of trying through film to create smell—to suffuse the visual with so much texture as to solicit the olfactory.17 The smell of Documenteur is unmistakably that of mildew, a rare stench in a town of arid winds. Varda seems to be poking around in a part of the city that has not been properly aired.

As Emilie looks for housing, she and Martin encounter a city left to rot: dangling wires, peeling paint, toothless addicts. They visit a seedy Laundromat, stepping over a man passed out on the floor, and wash their clothes in machines covered with graffiti. Finding a worn-down place to live, Emilie moves out from her friend’s living room and begins to scavenge furniture off the street, despite Martin’s protestations. Martin will not mention his father, but he will beg his mother to not unpack their boxes, not buy furniture, and to let him sleep in her bed instead of his own. Such trivial arguments elliptically suggest Martin’s sadness, which Varda refuses to poke or prod or fix, forcing the proverbial city of sunshine to countenance its melancholy. Emilie and Martin have just one conversation about grief. At a hamburger joint with fluorescent lights and vinyl swivel chairs, Martin tells his mother that he would cry a “King Kong cup of tears” if she died, or, he adds thoughtfully, if someone “put out his eyes.” His talisman against pain is his mother, but his mother’s talisman, he seems to understand, is her eyes.

Reprieve from depression and urban decay comes in the form of Emilie’s fantasies about her former lover, the man she’s just left. She daydreams about his naked body, sometimes as a naked object and sometimes coiled around her. Varda films these eroticisms deliberately, resting the camera on his penis or ear, until the anonymous lover becomes something more like textured landscape than corporeal form. (In all of Varda’s sex scenes, she renders skin with the same enthrallment that she elsewhere films wood grain, rotten potatoes, and the aging spots on her hands.) Having eliminated warmth from the Los Angeles urban environment, Documenteur finds it instead in Emilie’s erotic imagination.

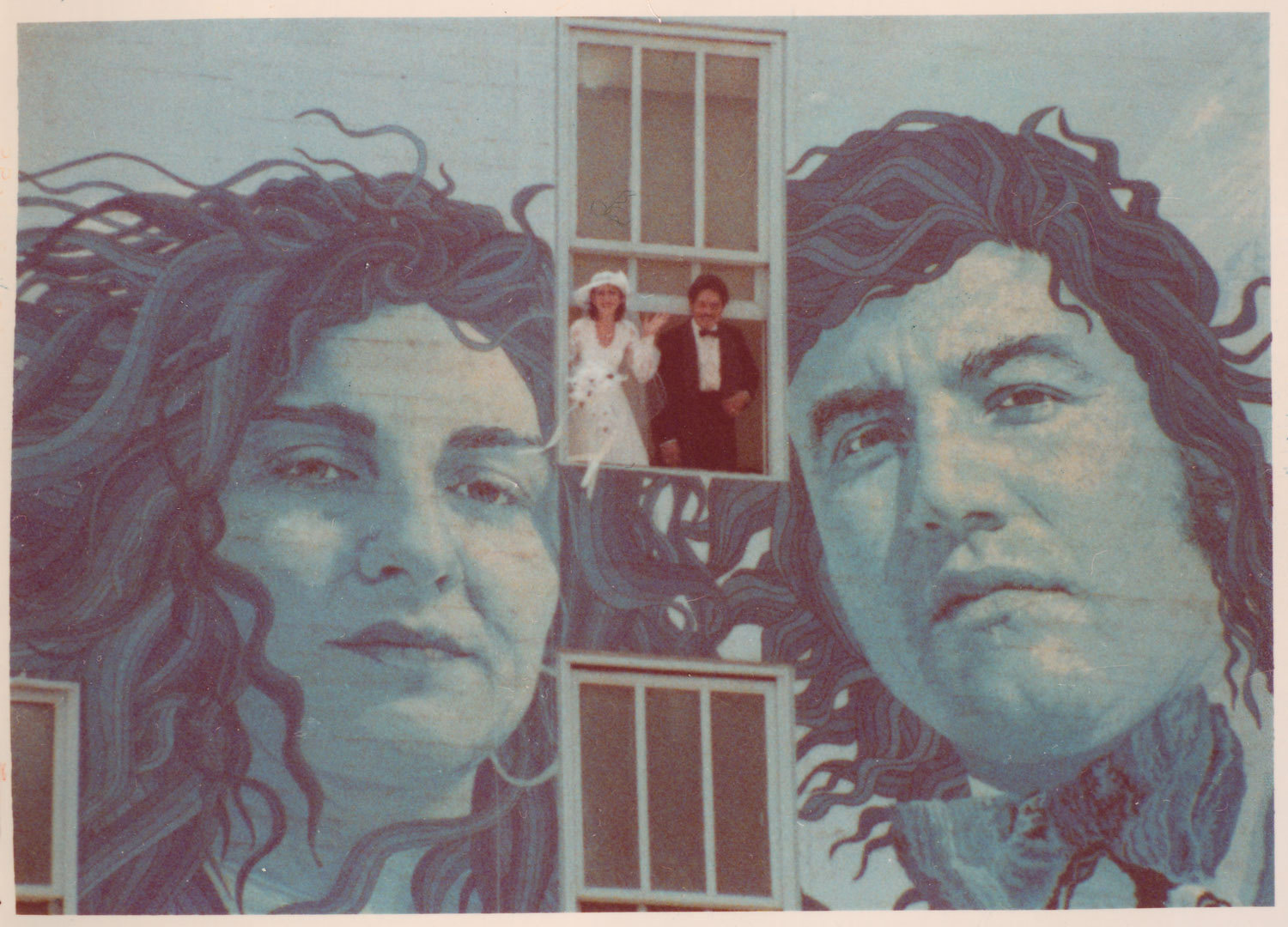

Agnès Varda, Mur Murs, 1981 (still). Color film in 16 and 35mm, 81 min. Courtesy Ciné-Tamaris.

Whereas Documenteur yields few explanations, Mur Murs incessantly pursues them.18 A mural is never just a painted wall in Mur Murs but a picture with a story, the outside of a particular inside. Varda is not content with the adage that Los Angeles is a city of surfaces; at each stop on her tour of the city, she peels back a facade to reveal what lies beneath, creating in effect a Los Angeles travelogue turned inside out. Varda lingers on the teenager who decided to paint murals while he was riding in the back of an ambulance with his brother after a gang shooting and the artist who paints afghan blankets because they remind him of his grandmother and because they last longer than cars. As is her habit, Varda coddles her eccentrics, making the film as amusing as it is beautiful: the juggler ex-soldier who works in “evangelistic Christian theater,” a blond singer with sunburned cleavage whose portrait is painted on the side of her house, the born-again Christian who depicts the Holy Trinity as television actors. She takes a special delight in murals that clash with the buildings they clothe. A Culver City DMV is decorated with scenes of space travel, and Pig Paradise, a mural about happy pigs, decorates the exterior walls of Farmer John’s pig-packing plant in Vernon.19 Varda asks the artist—an Austrian who has painted some 2,000 leaping, smiling pigs in 12 years of factory employment—if he likes to eat pork, and he replies that he does at breakfast.

The same mural that concludes Mur Murs opens Documenteur: LA Fine Arts Squad’s Isle of California.20 The massive painting depicts a broken concrete highway precipitously perched on an island, dangling above a foamy ocean. Split from the mainland, Los Angeles is in ruins. Without the West, the edge of the West has become a nowhere. Varda once described Documenteur as a film about the “end of the end of the end,” a phrase that also evokes the cataclysm to which this mural alludes, the specter of a catastrophe that will plunge Los Angeles into the sea.21 The ocean reclaims and gifts land at will, such that the end of the end will at some point meet its end. In this respect and others, Varda’s Los Angeles films insist on exposing the city’s secret substratum—the geological precariousness, the outsider’s take on Hollywood, the painful slivers of loss endemic to Angelenos’s propensity for self-invention. If only Faulkner and Fitzgerald and Brecht and all the others had seen Los Angeles as Varda did—as a city of seekers and misfits teetering on the edge of the world—they would not have hated it as they did. Of course, to find that Los Angeles, they would have had to leave Hollywood.