In other words Leavitt is interested in those characteristics of the movies which can be traced back to an earlier form of popular entertainment, the kind of theatrical performance which is called melodrama. Melodrama is that kind of romantic drama which depends on sensational incident and exaggerated appeals to conventional sentiment. The

tend to be stock characters who are shown to undergo little real development, merely moving from one highly charged scene to the next in order to offer the audience the comforting release of watching emotionally fraught incidents within a framework which provides the safety net of conventionality. The overall situation is always perfectly clear, the audience knows which character and which cause deserve sympathy, and if at any moment there should intrude an element of uncertainty, the music, which plays a tremendously important role in this kind of theatre, will provide the necessary clues for a correct understanding.

As the movies developed, directors and audiences alike began to respond in ever more sophisticated ways to the basic melodramatic format. In time it was only those movies produced to formula (horror, Sci-fi, thrillers), usually on a low budget, movies designed to make money quickly by appealing to a small, defined audience, that held to the simple dictates of melodrama. Popular movies for a mass audience, and their offspring on television, have a more complex pedigree. Character, or rather the betrayal of identifiable characteristics of personality, is more important, providing the director greater flexibility in his quest to keep the audience hooked. For the same reason the stories told in such movies tend to be more complicated, less predictable; although their endings remain uplifting, eschewing, for the most part, any hint of moral ambiguity. The basic underpinning, however, does still remain akin to that of melodrama. Only it is now expressed with more subtlety, in the accoutrements of the story, the seemingly peripheral elements like location, sets, props, lighting. The techniques of film making, the camera work and editing, also play a role, but a more complex one, and one beyond the purview of this discussion.

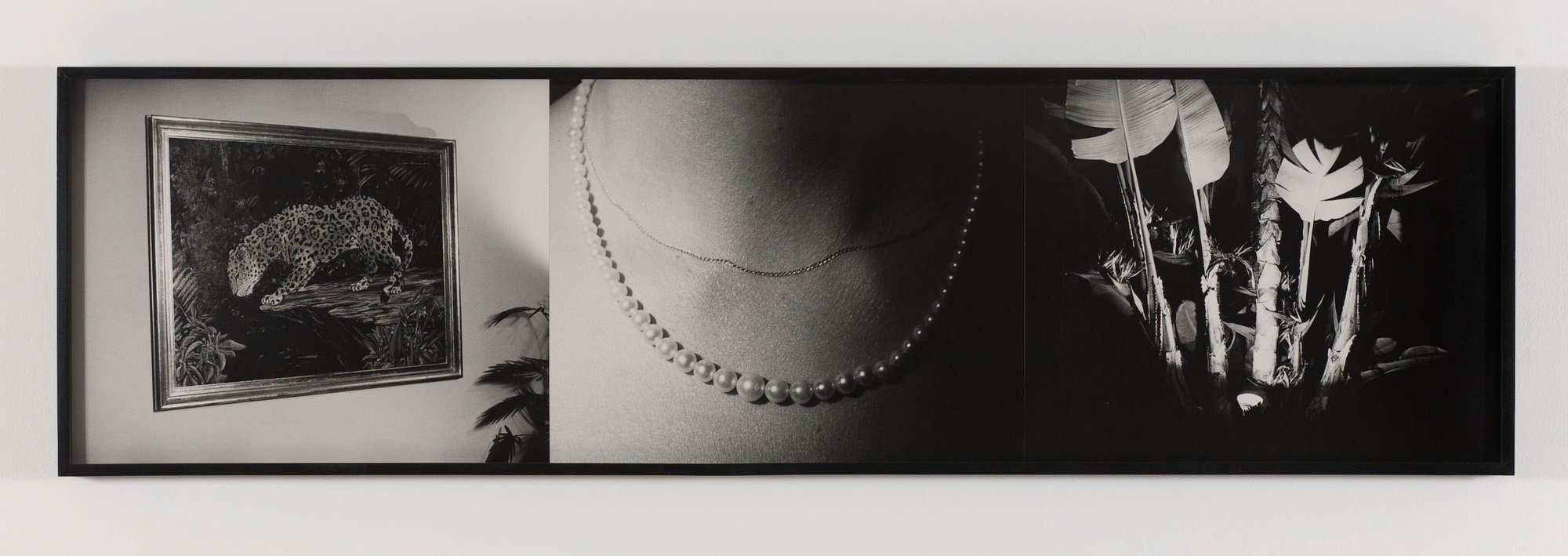

It is this uncertain area, the gap between a story and its telling, which seems to attract Leavitt. He virtually discards narrative, retaining only what is essential to indicate the situation. Instead all of his attention is focused on the representation; on those details, pregnant with meaning, which silently fill out any tale. By removing an easily recognisable kind of location (an elegant apartment in Los Angeles for example, or a hotel room in South America) from its context within the flow of a particular narrative, he demonstrates the potency of such images to generate an emotional resonance. For the sets are so loaded with the memory of past incarnations that by themselves they can suggest a great many, surprisingly similar, possibilities. Which is to say that he demonstrates their power as clichés to move a narrative along, without effort, to its expected end.

A clear example is to be found in the short treatment for a film to be called

The Lure of Silk, which Leavitt worked in 1974. Four scenes are proposed, three depicting a search of some sort, the fourth a record of fulfillment. In the first scene a camera at ground level tracks a pair of bare feet stumbling over stones, getting bloodier and bloodier. In the second scene two men are lost in the jungle, desperately hacking through a thicket of bamboo. The next location is a hotel room in the tropics in which a man, holding a drink in one hand, tries to make love to a disinterested woman wearing a tight silk dress. The final scene, a modern apartment with white leather chairs and glass-topped coffee table, is equally familiar to anyone who watches movies or television, and equally exotic. In this room a young woman is looking through a pile of snapshots. She stops to look at one more closely, a picture of whirlpool, and as she does so the camera moves in to include only this image in the frame.

The source, in general terms, of the first three images should be fairly evident. The final cut, however, introduces a new perspective on Leavitt’s work, for it recalls the image which, in slightly altered form, frames the central action of Joseph Cornell’s

Rose Hobart. In that film the circular ripples made when a woman drops a pebble into a pool are made to serve as a metaphor for sexual fulfillment, a metaphor similar to that famous one used by Buñuel in

Un Chien Andalou, a metaphor of a sort described by Freud as common in the dreams of those whose sexual lives are unsatisfactory. Cornell’s use of such a metaphor to open and close his erotic reverie is straightforwardly apt, Leavitt’s use is more ironic. It is infected by a sense of complicity, a weary recognition in the face of a terrible over-familiarity.

William Leavitt, The Silk, 1975. Performance, Barnsdall Park Theater, Los Angeles.

The year following

The Lure of Silk, Leavitt produced his most extensive work to date, a drama in five scenes simply called

The Silk. Combining elements from all his previous analyses of the mythic structures underpinning so many of the productions of Hollywood, it has a circular structure unlike the earlier, linear pieces, as if to recall the whirlpool metaphor. In

The Silk the characters are reunited after an absence, only to drift apart again. The action takes place in the by now familiar apartment, this time provided a magnificent view of the city rather than a plant-filled patio. Other details have been changed too; the painting is no longer of a jaguar, but of a lushly blooming orchid. The central token of the sexuality of the couple has been altered, a silk dress rather than a string of pearls. Otherwise the premise remains the same; the drama is acted out by the props, the actors are incidental, necessary only to provide the motor energy to move emphasis or attention.

In March of this year [1979] Leavitt presented a new tableau at Artists Space in New York. It is evident that he is still interested in the same issues that informed his earlier work, but he seems to have moved on to a new range of material. This latest set was more abstract, more stagey, than any of the apartments. This time it was an outdoor scene, a cafe, possibly European. A small table and two chairs, painted gold, were placed before a red drape. Over to one side stood a young tree and, in the background, the dark silhouette of an equestrian statue merged into the black drop cloth which closed the scene. On a quiet day one could hear birdsong.

These trappings are more obviously romantic, but still recognizably part of the stock in trade of movie melodrama. As before, the space vibrates with an unspecific quality of unease. Something is going to happen; but it may be something trivial. Nevertheless we want to know: who is going to meet here, what will happen, will it be friendly, or violent, will it lead to anything further, or just stop here? The questions are endless, but the witnesses remain mute. Anything can be projected, nothing confirmed.