Experiments in Print: A Survey of Los Angeles Artists’ Magazines from 1955 to 1986

by Gwen L. Allen

Back cover of Straight Turkey Vol. 1, Issue 2 (June/July 1974). Courtesy of Timothy Silverlake.

Artforum is an art magazine published in the West—but not only a magazine of Western art. We are concerned first with Western activity but claim the world of art as our domain. Artforum presents a medium for free exchange of critical opinion.

—Editorial statement, Artforum 1, no. 1, June 1962

The emergence of Los Angeles as the “second city” of American art, as art historian Barbara Rose once called it, was witnessed by Artforum’s tenure here. Founded in San Francisco in 1962, the magazine focused almost exclusively on West Coast art during its first few years and sought to be an alternative to the mainstream New York–based art press. Yet Artforum’s short stint in Los Angeles, from 1965 to 1967, proved merely a stepping-stone on the way to New York, where it was soon lured by East Coast prestige and advertising revenue.1As Peter Plagens later recalled, “There was a tremendous sense of betrayal in the LA art world. […] When the magazine went to New York, the strange thing was that everybody in LA still read it and everybody resented it. There was a lot of resentment in the art world that I knew: ‘Oh, my God, what are these arrogant assholes in New York going to tell us is cutting edge now?’”2Even some East Coast–based artists disapproved of Artforum’s narrowing New York–centered perspective. In 1969, Donald Judd complained, “Artforum, since moving to New York, has seemed like Art News in the 1950s. There’s serious high art and then there’s everybody else, all equally low. […] Bell and Irwin hardly exist; Greenbergers such as Krauss review all the shows.”3

To be fair, California art did continue to receive a fair amount of media coverage in the pages of Artforum and other art magazines. However, the mainstream art press tended either to ignore the local specificity of Los Angeles art, reading it through the lens of the dominant New York aesthetic, or to essentialize it in a kind of geographical determinism.4In this same period, though, art magazines and artists’ magazines were pivotal to the development of local and regional art scenes outside of New York.5Such magazines included Artweek in Oakland; La Mamelle and Vision in San Francisco; The New Art Examiner and The Original Art Report in Chicago; Sunday Clothes in South Dakota; Criss Cross Communications in Boulder; and Art Papers in Atlanta.

A history of Los Angeles artists’ magazines might look back to Wallace Berman’s Semina, a loose-leaf compilation of collages, photographs, drawings, and texts that the artist printed on his mail order Kelsey tabletop hand press from 1955 to 1964.6Another important early Los Angeles artists’ magazine was Landslide, published anonymously by William Leavitt and Bas Jan Ader from 1969 to 1970. The magazine caricatured the art world with fake interviews and pseudonymous contributors, and its title referenced the collapsing California hillsides as a spoof on the prevalence of earth art. Its format evolved from a mimeographed and hand-stapled zine into an “expandable sculpture,” consisting of several packing peanuts in an envelope. One issue was, allegedly, an actual McDonald’s hamburger mailed out in a cardboard box.7

In their DIY, idiosyncratic formats, irreverence, and offbeat humor, both Semina and Landslide seem to capture something of a distinctly Californian character. However, the attempt to forge a regional identity became more self-conscious and pronounced in the artists’ magazines of the 1970s and ‘80s. Los Angeles was an especially fertile region for artists’ magazines at this time, giving rise to publications, including the L.A. Artists’ Publication, LAICA Journal, Intermedia, Straight Turkey, The Dumb Ox, Choke, Criss Cross Double Cross, Chrysalis, The Performance Art Journal, and Spectacle. These magazines played a vital role in the experimental practices that defined Los Angeles art during this period, nurturing a local artistic community by fostering dialogue both within and beyond it.

This is the first issue of a communication exchange between Southern Californian artists and their friends.

—Editorial statement, L.A. Artists’ Publication 1, no. 1, May 1972

The L.A. Artists’ Publication was published by former Artforum critic Fidel Danieli, who was committed to a local art scene in Los Angeles. As he explained in the first issue, the publication’s purpose was “to provide a collective sense of inter-relatedness through a publicly available and easily copied distribution method.” The magazine was an “assembling”—an insistently democratic format in which each contributor submitted a specific number of copies of their work (in this case, 600) to be collated by the editor and distributed free of charge.8 The magazine consisted largely of documentation of various kinds of conceptual-oriented practices, some of which were site-specifically produced for the page. For example, Eleanor Antin cleverly made the magazine’s production process the basis for a work in which she listed various “renunciations” (such as hours of babysitting, cab rides, long-distance telephone conversations, books, and records) that equaled the $8 cost of printing her contribution. The publication’s generic title was meant to be temporary until readers voted on a more permanent title, but L.A. Artists’ Publication stuck. Danieli initially planned to assemble six bimonthly issues, but apparently ended the magazine after issue number 4½ in 1973. Soon after, he went on to cofound the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (LAICA) as well as the LAICA Journal.

The Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art is a new concept designed to be a catalyst for the support and recognition of contemporary art in Southern California. […] An exhibition program reflecting many concepts of high artistic achievement uses visiting curators from all sectors of the community and open, depoliticized selection processes. This bimonthly journal is being published to focus on the critical issues facing contemporary art.

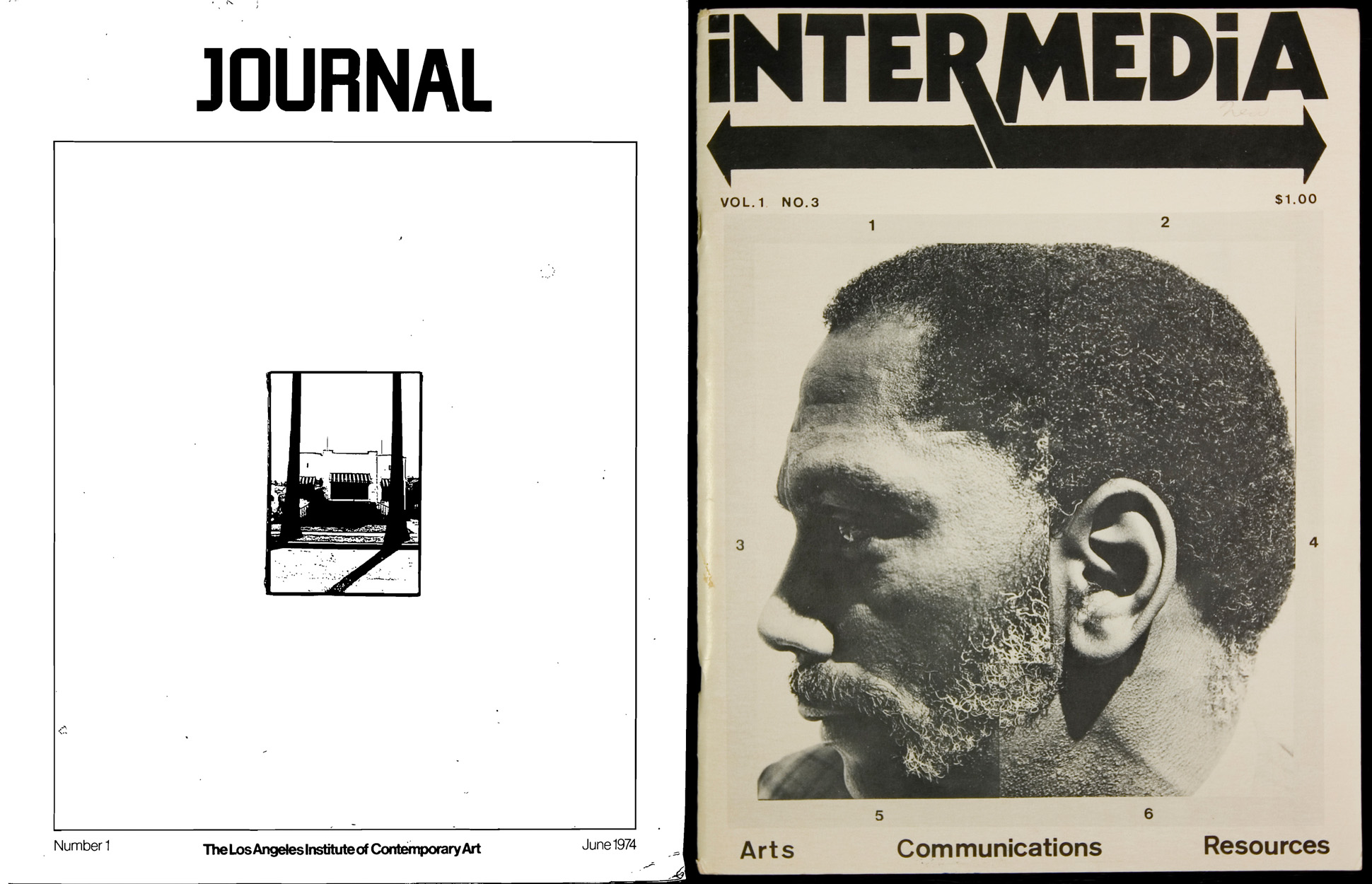

– Editorial statement, LAICA Journal 1, no. 1, June 1974

Like the numerous other artist-run cooperative galleries and collectives that emerged in a grass-roots fashion in North America in the 1970s, the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art was founded to support experimental artistic practices in a noncommercial setting that prioritized the needs of artists over those of dealers and curators.9 Artists’ publications were pivotal to the practical and ideological goals of such spaces, offering an alternative form of distribution that paralleled, augmented, and sometimes even replaced the exhibition space itself. 10 Indeed, in the case of LAICA, the Journal actually preceded the building, suggesting its foundational role in the institution.

LAICA cofounder Bob Smith recalled a preliminary meeting with local artists at which Billy Al Bengston insisted, “We don’t need another gallery. What we need is a magazine.” He and Danieli soon found themselves sitting around his dining room table with examples of other artists’ magazines—among them Avalanche, Art-Rite, and Aspen—planning the first issue of the LAICA Journal. Following the example of Art-Rite, a zinelike half-tabloid publication for experimental and alternative art in SoHo, they originally wanted to print the magazine on newsprint, to emphasize its difference from glossy commercial publications, but discovered that it was actually cheaper to use coated stock. (It would later switch to newsprint for issues 11–29.)

From the beginning the Journal reflected a concern with the history and identity of the Los Angeles artistic community, publishing writings and works by artists, including Martha Rosler, Eleanor Antin, Allan Sekula, Allan Kaprow, Miriam Shapiro, Judy Chicago, Guy de Cointet, Rachel Rosenthal, Lowell Darling, Billy Adler, and Van Schley. In a piece in the first issue entitled “ARTFROM” (in Artforum’s signature font), Joni Gordon presented a comprehensive chart of Los Angeles galleries from 1963 to 1974.11The fourth issue, guest-edited by Antin, was devoted to exploring why artists were drawn to California. As she wrote in her editorial preface, “Why do artists, especially, choose to live here when admittedly it isn’t the center of the art world, which makes negotiating an art career a much more complicated and difficult process than would be the case, say, in New York?”12

Like so many artists’ magazines at the time, the LAICA Journal highlighted the potential of the page as an alternative medium and exhibition space.13Yet, if the LAICA Journal emphasized the magazine’s significance as a new kind of artistic medium, it equally explored its social potential as a communication medium for artists. A collection of statements by various members of the Los Angeles art community published in the first issue voiced some of the social concerns that guided LAICA at its inception. Entitled “Observations,” the statements functioned as a kind of collective editorial, demanding that artists gain control over their lives and economic circumstances, strengthen the Southern Californian art community, and address classism, sexism, and racism within the art world. As Lucy Lippard later observed, “Artists’ publications were and still are important not only for their content and educational information but also for the networking they generate. At a time when little politics appeared in art magazines (and if it did, it was treated as a separate category), these portable objects could be mailed around the country, sparking actions in other contexts.”14

One of the goals of Intermedia is to link the new art movement with these other alternative movements—to create a unified alternative force of artists, writers, workers, and radicals. […] We want Intermedia to be by and for artists, to be a forum for artists’ concerns and needs, to be a mode of interdisciplinary communications between the artist and the alternative learning people, radicals, communicators, and especially a mode of communication between artists of different media.

—Editorial statement, Intermedia 1, no. 1, 1974

Intermedia exemplifies how artists’ magazines participated in the ideological and practical goals of alternative space, by fostering solidarity and information sharing among artists and other kinds of cultural workers, and supporting artists’ moral and legal rights. Billed as “an Interdisciplinary Journal of the Arts, Resources & Communications, by and for the Communicator/Artist,” the magazine was published and edited by Harley Lond, who conceived of it as a kind of Yellow Pages for artists, writers, and musicians in the Los Angeles area and beyond. Intermedia included a listing of art services, organizations, small presses, and free artists’ classifieds. As suggested by its title, the magazine also supported conceptual and intermedia practices, which it showcased in different formats, ranging from an 8½-by-11-inch magazine to a tabloid newspaper; a compendium of posters; and a box containing unbound artist-designed postcards, broadsides, folders, and posters. Among its contributors were Martha Rosler, Clemente Padin, Richard Kostelanetz, Opal Nations, Dick Higgins, Anna Banana, and Lew Thomas.

Straight Turkey Vol. 1, Issue 1 (September/October 1974). Courtesy of Timothy Silverlake. To download a PDF of Straight Turkey Vol. 1, Issue 1 (March-April 1974) click here.

The material presented in this magazine is done so because it is a representation of attitudes and work presently being undertaken in the art community.

– Editorial statement, Straight Turkey 1, no. 1, March/April 1974

One of the most important ways in which artists’ magazines sought to empower artists in Los Angeles during the 1970s was by providing a place for artists to speak about their own work. To this end, Straight Turkey published interviews with and writings by Los Angeles–based artists and critics, including John Baldessari, Peter Plagens, Claire Copley, Barbara Munger, Walter Gabrielson, and Theron Kelley. The magazine’s title (which evolved from issue to issue and was sometimes left off entirely) was meant with a wink, referring to an expression at the time loosely meaning “genuine article” or “straight talk.” To preserve the integrity and authenticity of the artist’s voice, editor Timothy Silverlake insisted that all material be printed in as unfiltered a manner as possible, unedited except for typos, and that interviews be conducted spontaneously and transcribed verbatim—a policy he explained as “a reaction against the politics of validating art, a system that has gotten us to the point of intellectual elitism and far away from the reality of the artistic process, a process that I would think is worth maintaining.”15While Straight Turkey folded after a mere three issues, it served as the inspiration for a subsequent magazine, The Dumb Ox.

Why The Dumb Ox? We have no axe to grind, only an ox to feed. We are looking for contributions from all varieties of talents. Send us articles and/or artworks so that we may satisfy the hunger of our ravenous beast. The Dumb Ox enjoys grazing on a myriad of disciplines, loves to ruminate on problems tangential to the various arts. He has been known to severely gore all the ineptitudes found in the status quo!

– Editorial statement, The Dumb Ox 1, no. 1, Summer 1976

When artists Theron Kelley and James Hugunin founded The Dumb Ox, they were recent MFA graduates who felt “very dissatisfied with the Los Angeles art/photography scene and wanted to put forth an alternative critical voice that would also provide exposure for many artists we felt were being marginalized (especially conceptually oriented artists) by the art establishment in LA.”16The magazine published articles, reviews, and interviews, and managed to be critical without losing its sense of humor. For example, when the curator Maurice Tuchman was too busy to grant an interview, the editors published a “Do-It-Yourself Interview” consisting of the questions they had wanted to ask him with blanks for readers to fill in their own answers. Number 10/11 was a special issue on performance art, guest-edited and designed by Allan Kaprow and Paul McCarthy. (In 1977, McCarthy also published a single issue of Criss Cross Double Cross, a tabloid-format magazine containing artists’ projects.)

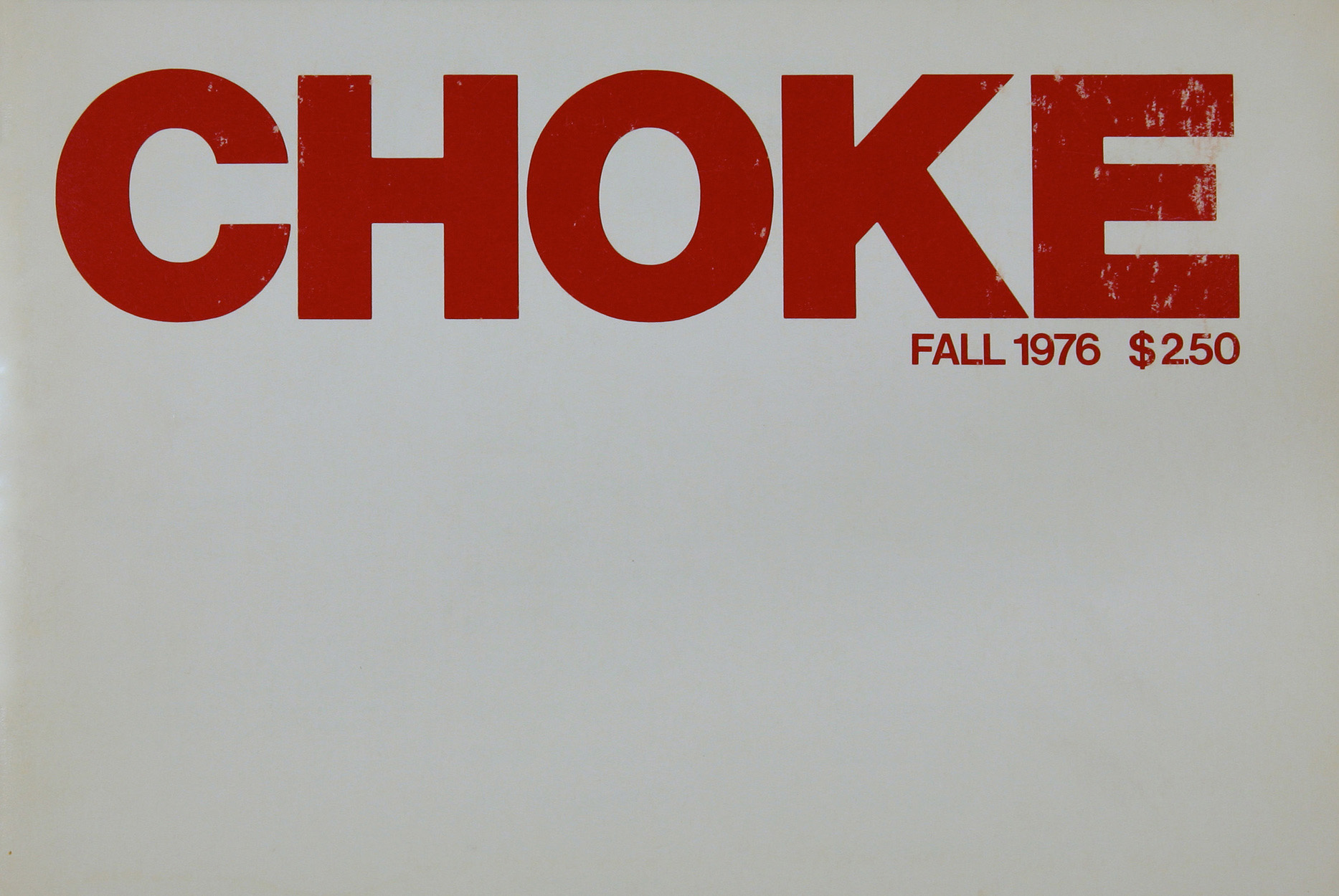

Choke is a magazine format providing possibilities for expression not usually available to artists. […] With few exceptions, artists have very little control over information about their work appearing in printed media.

– Editorial Statement, Choke, Fall 1976

Cover of Choke 1 (1976). Courtesy of Barbara Burden and Jeffrey Gubbins.

A single issue of Choke was published by Barbara Burden and Jeffrey Gubbins in 1976. The magazine’s title—a reference to the air quality in Los Angeles—was, according to the editors, also a wry comment on the way in which West Coast artists felt suffocated by the East Coast art world. It published original works and writings by Bruce Nauman, Chris Burden, Guy de Cointet, and Billy Adler. The editors vowed to publish a cost breakdown for each issue, explaining that the magazine’s policy of economic transparency ran counter to the approach of more mainstream art magazines, which depended on advertising by commercial galleries. Choke rejected paid advertising entirely—a strategy that unfortunately led to its demise after the first issue.

Too much performance art has been lost to history. Therefore, High Performance is open to any artist who is organized enough to send me good black-and-white photographs and a clear description of what occurred. I ask for material directly from the artist because we have relied too much and too long on criticism.

– Editorial statement, High Performance 1, no. 1, June 1978

High Performance was founded by Linda Burnham to foster performance art as its own medium apart from dance, theater, and music. Following an open submission policy until 1982, the magazine published documentation of specific performances with photographs and artists’ texts, as well as interviews, reviews, articles, and occasionally fiction and poetry. A crucial archive of performance art in general, it witnessed the salience of such practices in Southern California, in particular, with contributors, including Suzanne Lacy, Linda Montano, Carolee Schneemann, Rachel Rosenthal, the Lesbian Art Project, Paul McCarthy, and Chris Burden.

When an insect emerges with struggle from its chrysalis state, how feeble are all its movements […]. This illustrates the present condition of Woman. She is just emerging from the darkness and ignorance by which she has been shrouded.

– Sarah M. Grimké, quoted in editorial statement, Chrysalis 1, no. 1, 1977

One of the things that defined the Los Angeles art scene in the 1970s was the prevalence of feminist and nonwhite art practices. In the very first issue of the LAICA Journal, the art historian Judith Bettelheim stated, “Artists are already talking to each other. They don’t need to increase the dialogue or exchange among themselves. What they need to do is to cut through social classes and increase a dialogue with minority artists.” This same issue of the Journal featured the CalArts Feminist Art Program. Three years later, in 1977, Chrysalis: A Magazine of Women’s Culture was founded to foster feminist art practices in Los Angeles and beyond. Published by women for women, Chrysalis featured interviews, essays, fiction, and poetry, as well as a resource catalog. Among its contributors were Lucy Lippard, Michelle Wallace, Linda Nochlin, Judy Chicago, Carol Duncan, Arlene Raven, and Mary Beth Edelson.

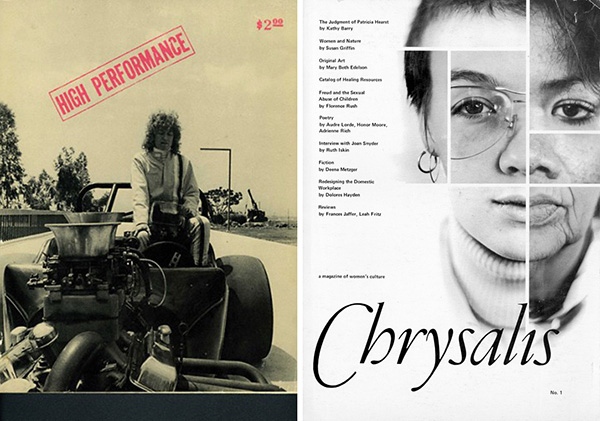

Left: Cover of High Performance Vol. 1, No. 1 (June 1978). Courtesy of Lynda Frye Burnham. Right: Cover of Chrysalis: A Magazine of Women’s Culture. Vol. 1, Issue 1 (1977). Courtesy of Kristen Grimstad. To download a PDF version of Chrysalis: A Magazine of Women’s Culture Vol. 1, Issue 1 (1977), click here.

Los Angeles is hard to know. It looks familiar: It’s a town we all grew up in, right there on the television set. […] If it is true that everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation, then Los Angeles is the site of that process. […] There is power here. This magazine offers Angelenos a forum for the critical appraisal of the industry of media representation.

– Editorial statement, Spectacle 1, no. 1, 1984

Spectacle: A Field Journal from Los Angeles published artists’ writings and works that explored media representations. While such practices are most often associated with the New York–based Pictures Generation, Spectacle emphasized the importance of Los Angeles to these practices (several of the Pictures artists had, in fact, studied at CalArts) while suggesting how such practices were shaped there by the city’s proximity to the film industry. Like previous artists’ magazines, Spectacle suggests how Los Angeles art took place in dialogue with advanced artistic practices elsewhere, yet was also inflected by the city’s specific geographical and cultural conditions.

These conditions not only affected the art produced in Los Angeles, but surely shaped the character and role of artists’ magazines themselves. Indeed, artist Thomas Lawson, writing in his 2010 foreword to East of Borneo, reflected back on his own impressions of Los Angeles during a visit to the city with Susan Morgan in 1980, a period in which they were publishing REAL LIFE (1979–94), an important experimental artists’ magazine for the Pictures artists in New York. Driving around Los Angeles in a borrowed 1960 Rambler, they observed the very different experience of producing a magazine within the suburban sprawl of Los Angeles than in the densely inhabited urban grid of Lower Manhattan:

We experienced an expansive feeling of discovery as we drove the freeway, gaining a sense of place much broader, but also less specific than we knew in Lower Manhattan. There, most of our daily business was conducted on foot, meeting and talking to people face-to-face, often in unplanned encounters. In many ways, we lived as villagers, members of a shadow community of artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers who walked the same streets, frequented the same bars and restaurants, dropped in on the same galleries, performance spaces, and movie theaters. […] Coming from New York, we found [Los Angeles] both exhilarating and baffling; Los Angeles seemed to be a city hiding in plain sight. There was plenty to see, interesting people to talk to, all easily accessible by the sporadically flowing freeway. But that veneer of easy connectivity masked a deeper, and more troubling, sense that nothing was easily available, a misleading perception of nothing going on. This was a city of outposts and easily missed landmarks connected by a sprawling, historical disposition not to connect.17

Yet despite—or maybe partly because of—the city’s notoriously sprawling disconnectedness, Los Angeles artists have sought connections with one another and with a public, as the publications surveyed here attest. Indeed, in some ways, the lack of a center that defines the Los Angeles urban structure—all margins and fringes and edges—corresponds to the dispersed, distributed nature of printed publications themselves. Artists’ magazines enabled communication and relationships between those who might not otherwise have come into contact with one another, spreading ideas and sustaining dialogue over space and time. In doing so, they shaped the history of experimental art in Los Angeles in the 1970s and 1980s in crucial ways.

Among other things, this history prompts reflection on the role of artists’ publications today, a moment in which online media are opening up new possibilities for artistic experimentation and communication. Relinquishing the tangibility of the printed page, web-based publications offer vastly different kinds of materiality, spatiality, and temporality, which in turn alters their capacity to mediate between local and global audiences, their potential for interactivity, and their ability to foster publics within and outside the art world. These possibilities can’t be fully predicted but will take place alongside and in a reciprocal relationship with changes in artistic practice, art criticism, and exhibition spaces. However, the history of artists’ magazines, including the ones discussed above, might inform and inspire the possibilities for publications today, whether online, printed, or some combination of the two.