Hand in Glove: Reflections on LAICA Journal and Culture Endowed

by Lane Relyea

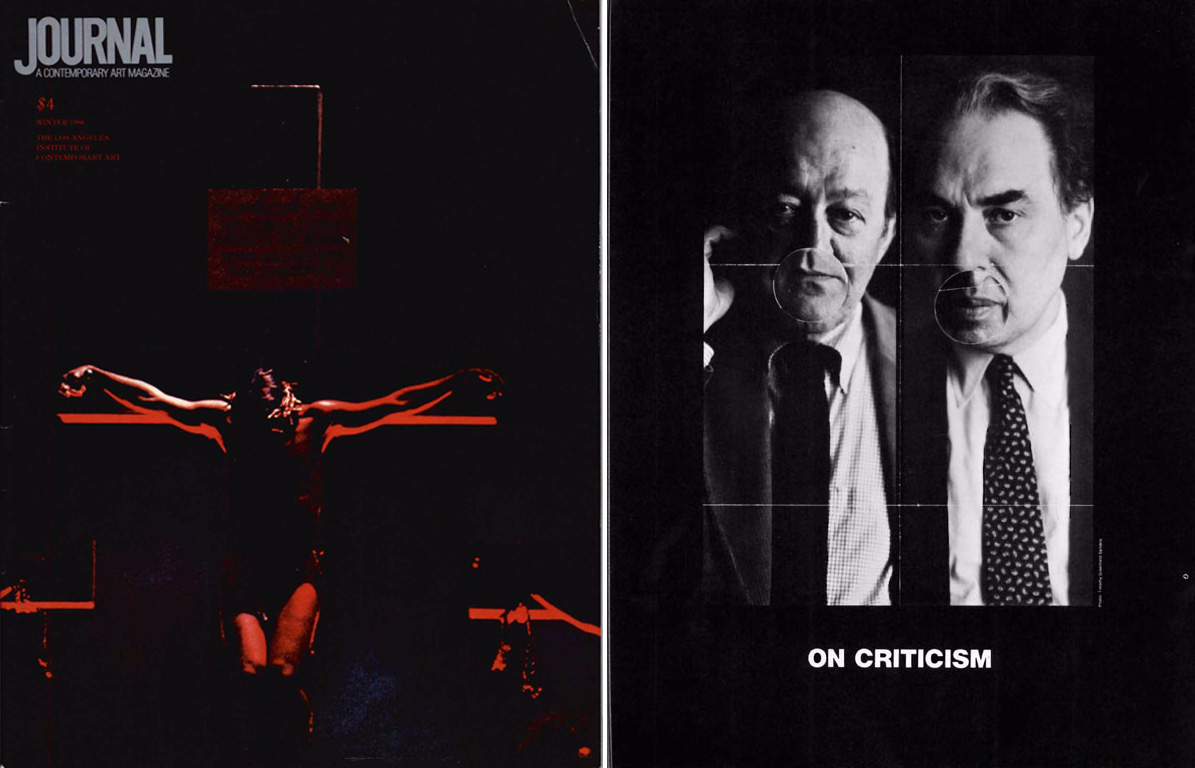

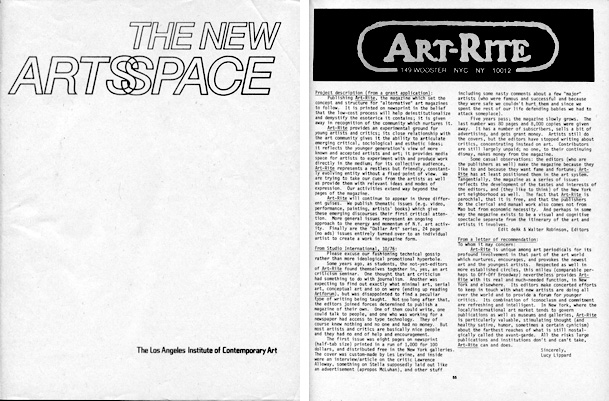

Cover and interior illustration of LAICA Journal Vol. 5, No. 43 (Winter 1986). Left: Mark Greenberg, from Crystal Cathedral’s Annual Presentation of the Glory of Easter, 1984; Right: Ron Linden, On Criticism, 1986. Pictured: Clement Greenberg and Hilton Kramer. Courtesy of Robert Smith.

In October 2011 in Chicago, amid one final blessing of bright, late-summer weather, the local nonprofit Threewalls played host to a weekend conference of “independent arts organizers” from across the country, a throng of mostly young people from cities (Detroit, Minneapolis, St. Louis, etc.) with contemporary art scenes that, like Chicago’s, manage to survive by means other than commercial gallery sales.1I was asked to participate as the moderator of a panel about the history of artist-run spaces in the 1970s and ’80s. Really, my job boiled down to introducing special guests Renny Pritikin and Martha Wilson, two legends of the seventies alternative-space movement. (Martha founded New York’s Franklin Furnace; Renny was an early director of New Langton Arts in San Francisco.) It was a moment steeped in torch-passing symbolism, but there was also a very precise precedent that these two esteemed elders were intended to represent. They had both participated in a similar conference more than 30 years earlier, the first-ever national gathering of representatives from artist-run spaces, which was held at the Miramar Hotel in Santa Monica in 1978.

From the casual groundwork laid by that initial get-together, titled The New Artsspace conference, grew the mighty National Association of Artists’ Organizations (NAAO), officially launched four years later as a powerful federal lobbying arm with close ties to the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). Much of my own early history in the art world was spent editing magazines published by alternative spaces; indeed, this experience led to NAAO asking me to serve as the editor of its tenth-anniversary catalog, published in 1992.2But I entered this world a little later than Renny and Martha, in the early eighties, and thus the memories I had to share at the Chicago conference were dominated not by heroic mainstream-defying deeds but by resentful tales of grant-writing drudgery. The NEA had encouraged an overbureaucratization of artist spaces during the eighties—until, that is, culture warriors like Jesse Helms abruptly eliminated nearly all federal funding of contemporary art and artists. Such was the touch of cloudy gray I managed to insert into that otherwise optimistic, sunny Chicago ceremony.

Among the main promises made in the early days of artist-run spaces, beyond the commitment to non-object-based, noncommercial artworks, as well as more raw and democratically decided exhibitions, was a new breed of art magazine along with a new criticism. Thus, also in attendance at that initial 1978 conference—shoulder to shoulder with members of such rouge outfits as New York’s Artists Space, Chicago’s N.A.M.E. Gallery, and the Washington Project for the Arts—were Edit deAk and Walter Robinson, editors of the upstart magazine Art-Rite.3 The alternative-space movement, they told the assembled crowd, was ushering in a brand of art press opposed to the narrow, monolithic criticism of the sixties. Yes, the existence of avant-gardes was still being confidently proclaimed (deAk and Robinson called these the “voices of the new,” publications “working closely with” and “advanc[ing] the interests” of select artists); and, yes, authoritarian, quasi-modernist judges were still discriminating between the serious few and the trivial hordes, in sober-sounding, text-heavy journals like the then-two-year-old October.4 But much more indicative of the seventies were the many newsletters and “picture magazines” (“a number of pages from each artist, like a catalog”); “lobbyists” (Feminist Art Journal and Art Workers News were two examples they noted); and, finally, the numerous “parochials”—local magazines popping up in towns across the country where the art scene revolved around one or two newly established college art departments, and perhaps also a new contemporary art center funded by the NEA.5 Production of art and artists was dramatically ramping up and decentralizing, and distribution and consumption had to keep pace. “Where the commercial structure attempts to consolidate and codify,” deAk and Robinson argued, “the alternatives try to accommodate.” I myself would spend eight straight years, from 1983 to 1991, working on “parochials,” first the Los Angeles–based Journal, and then, starting in 1987, the Minneapolis-based Artpaper.

Program for the New Artsspace conference, April 26-29, 1978. It included a directory of 57 alternative visual arts organizations from around the country, such as New York’s Art-Rite. To download a copy, click here.

The generically titled Journal was published by the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (LAICA), the same artist-run space that had organized and hosted the 1978 New Artsspace conference in Santa Monica.6The first issue of the Journal (or, as it was variously referred to over the course of its life and still is to this day in innumerable libraries and databases: the LAICA Journal or Journal: A Southern California Art Magazine or Journal: A Contemporary Art Magazine) was edited by the important West Coast critic Fidel Danieli and appeared in June 1974. Indeed, in an indication of how crucial the idea of a strong local art publication was in the early seventies, the magazine rolled off the presses nearly half a year before LAICA opened its first show. By the fourth issue, Danieli had ceded the helm to a string of guest editors, including Eleanor Antin, Peter Clothier, Marcia Tucker, Morgan Fisher, and, to coincide with the 1978 conference, deAk and Robinson.7 Curator Michael Auping edited three consecutive issues in 1977, but otherwise the closest thing to editorial consistency were the nine issues edited by Bridget Johnson beginning in late 1978 through 1981.8The Journal’s frequency was halting as well; up until 1981, it alternated between bimonthly and quarterly publication, after which it committed itself to a quarterly schedule while in fact managing to produce, at best, three issues per year. (Woe the librarians who had to catalog this thing.) At least the magazine’s measurements, 8½ by 11 inches, remained constant; the paper stock was upgraded from newsprint to glossy at the end of the seventies.

A distinguishing feature of many of the new alternative magazines was how they squared their cutting-edge self-image with their embrace of the artist-run ethos of their parent organizations. Rather than align themselves with a notion of criticism as gatekeeping and canon-making, they saw themselves as support mechanisms for the local scene, the achievements of which they documented and publicized. This is not to say that the writing in the Journal wasn’t opinionated and strong—frequent contributors included Frances Colpitt, Ruth Iskin, Christopher Knight, Susan Larsen, Suzanne Muchnic, Peter Plagens, Howard Singerman, and Melinda Wortz, among others—just that anything like a consistent position or perspective was assiduously avoided. In the words of LAICA’s founding director, Bob Smith, the mission of the magazine was to “represent a noncritical view, a view that artists would agree with about their work,” and thus to “serve [as] an intermediary between artists and the public.”9deAK and Robinson were more pointed: “A tough critical stance can seem like sabotage of the group interests. This is the bane of the house organ.”

When I arrived in early 1983, LAICA had moved from its original home in Century City to a space on Robertson Boulevard, a few blocks north of the 10 Freeway.10 The good old days were long gone, as were several crucial revenue streams: federal CETA grants funding arts employment had evaporated with the transition from Jimmy Carter to Ronald Reagan, and LAICA had, by that time, through its inevitable inability to make good on all its original promises and be everything to everybody, managed to alienate what initially had been a very enthusiastic and supportive local artist community. I interned at first, volunteering part-time between my undergraduate classes at UCLA to help in the Journal’s editorial office or with preparator work in the exhibition spaces. Michael Delgado, who had recently replaced Bridget Johnson as editor of the Journal, had just left; within a matter of months Delgado’s replacement left, too. Just like that, Bob Smith offered me the job of managing editor, an impressive name for what was at the time the Journal’s only full-time position. My inadequacy to the task at hand was as vast as my salary was microscopic. I stopped going to class and became a willing prisoner of LAICA’s small rooftop apartment, which Bob had converted into a typesetting and design room. (The bathroom and shower doubled as a developing and drying station for the still-very-soggy photo-based technology that typesetting was restricted to back in those days.) The typesetting machine was manned by famed Flux artist Jerry Dreva (aka Jerry Bon Bon) from 1980 through my first year there; with my promotion to managing editor, the typesetting duties were also unloaded onto me.11

John Knight, LAICA: When the Conversation Turns to Art, a work in situ at LAICA Gallery, 1984. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

I coaxed friends to volunteer help. My greatest feat of exploitation was talking local artist Peter Levinson into giving the magazine a design makeover that still looks freshly elegant to this day. When an issue came back from the printer, I would offer free pizza and beer to anyone who’d help sort and bag copies for the mass mailing of around 1,200 or so copies. A subscription came free with LAICA’s $25 annual membership fee; stand-alone subscriptions, though available, were few, as were retail sales, despite my efforts at setting up reciprocal advertising in magazines like High Performance, New Art Examiner, Real Life and Emigre, and a network of regional distributors that together covered most cities in the U.S. and some in Canada. Of course, I learned a lot and worked with amazing (and amazingly generous) people who I otherwise might never have gotten to know, like local artists and writers Dennis Cooper, Dana Duff, Amy Gerstler, Mike Kelley, Timothy Martin, Mitchell Syrop and Benjamin Weissman. But in my three years of heading the Journal, I managed to get only six issues out.

During that time, the larger situation at LAICA slid from bad to an ornately Kafka-esque version of bad. Bob had grown paranoid and resentful; and yet, with LAICA’s board and various committees increasingly riddled by vacancies as members resigned more quickly than replacements could be found, he exerted more and more executive power. A siege mentality overtook the scheduling of programs and exhibitions: Shows would be thought up as revenge for the dismissiveness of the rest of the art community. For example, a survey of paintings by the comedian and TV actor Martin Mull followed on the heels of an exhibition comparing the use of sports iconography in the work of Andy Warhol and LeRoy Neiman. With no money coming in, artists paid for vanity shows so as to fill holes in the calendar. (See, for example, the 1984 atrocity “The Big Candy” by Franco Assetto, husband of prominent West Coast music patron Betty Freeman.)

I often slept in my office; one morning I was jolted awake by an 18-wheeler that had lost control on Robertson Boulevard and crashed into the building, its front half coming to rest in Bob’s demolished office. Bob and his wife, Tobi, who worked as LAICA’s financial director, abruptly and unceremoniously walked away from what had been their brainchild and life’s work and left Los Angeles in 1985; not long after, the IRS threatened to shut the place permanently for failure to pay back payroll taxes. The person hired to replace Bob as director lasted less than a year, literally leaving LAICA in the middle of the night. Other accounting irregularities were discovered, and what remained of the board of directors decided to fire what was left of the staff, except for me—the Journal would continue as LAICA’s one surviving operation, thus buying the board and other interested parties a little more time to figure out a next move.12I was nearly done working on an issue of the Journal; once it got printed and put in the mail, I quit. Meg Cranston replaced me as editor and managed to publish four more issues before the Journal—and LAICA—were officially dissolved in 1990.

“The alternative publication seems destined to have appeared,” deAk and Robinson concluded at that conference in 1978. “It is easy, it is cheap, so go out and do it yourself.” Funny that I never, ever thought of the Journal as a do-it-yourself endeavor, not in the way we think of DIY today—not in the way, for example, all the young, idealistic arts administrators at the recent Chicago conference seemed to think of it. The reason is partly generational: The seventies were over, and culture in the early eighties meant blockbusters, spectacle, big corporate media. It was the “Pictures” generation; it was Michael Jackson’s Thriller and the Star Wars trilogy; it was hit radio and prime-time TV on only three major networks. But it was also about “big” government, about national politics and federal arts policy. My first year at the Journal coincided with the publication of Hilton Kramer’s famous denunciation of the NEA’s funding of critics and criticism in the neoconservative magazine The New Criterion.13 The accelerating attacks on the NEA throughout the decade made abundantly clear just how big the U.S. art world had become, how spread out it was across the country, and how dependent it had grown on the politicians in Washington, D.C. The right-wing assault on the NEA didn’t manage to stop the momentum of the art world’s growth and spread, but it did succeed in eliminating the national government’s role in it, including its encouragement and support of new art and living artists.14

Far right: Renny Pritikin, Martha Wilson, Lane Relyea, and Mark Allen on “Archiving Artist-Run Histories,” a panel at Threewalls’ Hand-in-Glove conference, October 2011. Courtesy of Threewalls, Chicago.

Very little talk at the Chicago conference addressed grant writing, and nobody spoke of the NEA. Instead, people discussed crowdsourced microsupport from colleagues, offered through mechanisms like fee-based classes and residencies, raffles and limited-edition art sales, and online fundraising tools like Kickstarter. Perhaps this change is for the better. No doubt, DIY resourcefulness provides relief amid the disempowerments and social divisions of large-scale industry, technology, professionalization, bureaucracy, etc. It also allows outfits to duck the official decrees, censorship, and other forms of state or institutional overpresence that overwhelmed much of the eighties nonprofit art world. And yet DIY seems not so oppositional when placed within the kinds of art institutional contexts one encounters more and more these days, specifically an underpresence of government as a result of neoliberal attacks on state redistribution mechanisms and security assurances as compensation for social inequality and injustice. Shifting focus onto individual actors and their immediate and intimate contexts and connections can have the unfortunate side effect of helping further obscure larger-scale issues of modern social organization like across-the-board fairness and protection. Contrast, for example, today’s DIY enterprises—many of which boast authenticity precisely for eschewing any claim to represent a public or art population beyond their respective inner circles—against the NEA’s original progressive mandate to dispense tax money so as to protect and encourage diversity among our nation’s forms of expression. That’s right: Not so many years ago, our government gave money to its critics. It should make us pause that such a fact strikes us as so bizarre and almost unimaginable today.