Humanness Always Comes First

by Kate Wolf

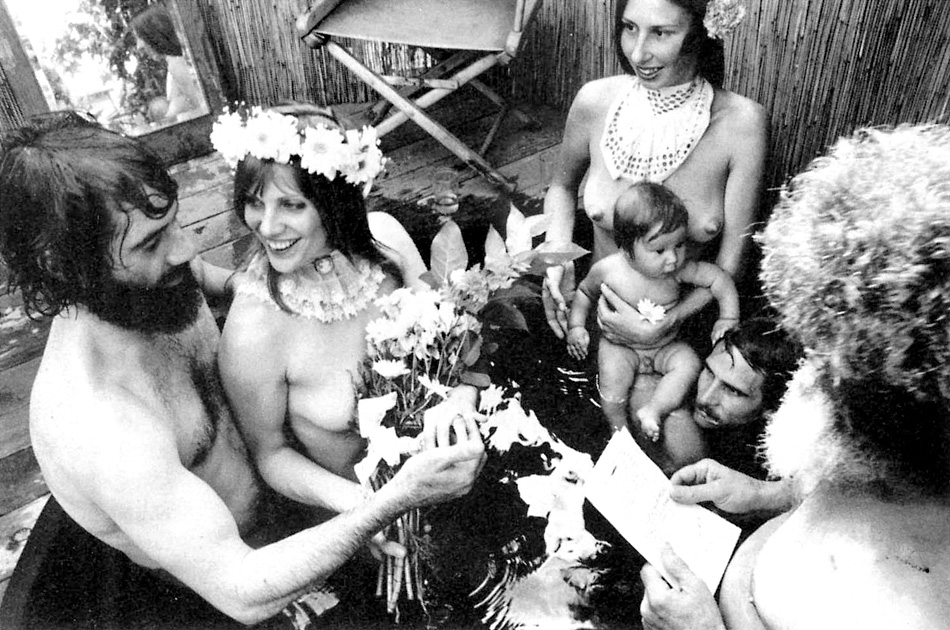

Robert Alexander (right) officiating a hot tub wedding ceremony in Venice, 1978. Photo: Lyle Mayer.

In all this, persons come first. None of the above is to be construed as a rule or regulation. Humanness always comes first!—Robert Alexander, Bulletin to Temple of Man Ministry1

Call it a sign of the times: In July 1979, as American divorce rates were peaking, Los Angeles magazine ran a tongue-in-cheek article about second (or third or fourth) weddings; a section of it, “Four Interesting People to Be Married By,” featured a picture of the Reverend Robert Alexander. He sits on a bench against a cloth backdrop, alongside a rabbi, a self-help writer, and a noted minister to a congregation of 10,000. His hands are folded together, and he wears a long black robe, with a full beard and bushy gray hair, a small crease in his brow, and a pensive expression of a slightly comic bent; “Groucho Marx as village priest,” as he was described by his friend, artist George Herms. The brief caption farther down the page reads,

Bob Alexander, longtime Venice poet and artist who’s exhibited at the Smithsonian, operates out of his small, warm, brown house in Venice (the “People’s Republic of Venice,” he calls it), headquarters of his ministry: the Temple of Man. He’ll marry you simply and straightforwardly in his study, on the beach, in a hot tub, even on roller skates along the bike path; he’s not a fan of ‘dogma, empty ritual or meaningless ceremonies.’ His temple is nonsectarian, so your religion or lack of it is no problem.2

Alexander was the creator and main force behind the Temple of Man, from its start in 1960 until his death in 1987. A nondenominational ministry, it was founded on the well-known maxim by one of Alexander’s closest friends, artist Wallace Berman: “Art is love is God.”3The Temple’s ordained ministers—fellow artists, writers, and other members of Alexander’s scene—presided over weddings, christenings, and memorials, combining the unique rites of each ceremony with art and poetry. (Kenneth Patchen was a favorite.) True to the calling, Alexander visited prisoners and hospital patients, advocated for the rights of drug offenders, set up an outreach to teach photography to inner-city youths, and was even active in local politics. But the Temple also published books of poetry, sponsored exhibitions, held readings and screenings, and, through donations, amassed a sizable collection of art.4The Temple itself became Alexander’s most ambitious and sustained artwork, integrating his previous output as a printer, poet, visual artist, organizer, and performer under a unifying equation, one that put creativity at the apex of existence.

The “warm, brown house in Venice” mentioned in the article—a 1910 bungalow where Alexander moved with his wife, Anita, in 1968—is still there, located at 1439 Cabrillo Avenue, just a block from Abbot Kinney Boulevard. It sits next to an alley that, despite the upscale boutiques steps away, retains the activities—the drinking, glass breaking, and dumpster scavenging—native to alleys everywhere. The house is now a vacation rental, decorated in a kind of modern surfer chic. I happened to stay there last year, dog-sitting for friends who had escaped New York for Venice and were at that moment escaping Venice for Hawaii. It had a luxurious, if innocuous, feel: The rooms were painted in shades of taupe and cream, with surfboards and large color photographs on the walls; the kitchen was full of top-of-the-line stainless steel appliances; a hot tub motor droned in the back next to an outdoor shower latticed by bamboo spears. Perhaps the only noticeable quirk was the upstairs walk-in closet, which, from the slant of the low ceiling, had obviously once been an attic.

So if it weren’t for a service notice that arrived one day from the American Air Conditioning and Heating Company in Inglewood, which was addressed to an acquaintance of mine, the artist Anthony Pearson, I probably would never have known that for the previous two weeks, I had been living in the former headquarters of the Temple of Man. Coincidence, as Albert Einstein wrote, may be God’s way of remaining anonymous, but in this case, it was the mode in which the work and life of Robert Alexander became known to me.

Alexander’s former residence at 1439 Cabrillo Avenue, Venice, California, photographed in 1996. Courtesy of Anthony Pearson.

The day I received the notice, I wrote to Pearson and he confirmed that he had indeed once lived in the house. He told me he and his wife bought it in 1996, in near-condemned condition, from Alexander’s stepchildren. Although other parts of Venice closer to the beach or on the canals were already expensive by then, with property values rising steadily since the 1962 removal of the last of the oil derricks that once lined Venice Beach, they were able to purchase it at the bottom of a real estate recession for just a little over $200,000. As Pearson remembered, Cabrillo Avenue and the neighboring streets still showed signs at that time of the destructive hold that drugs—particularly crack—had on many members of the community. A nearby liquor store actually sold glass pipe stems and steel wool filters at the counter, and the sidewalks were littered with the discards. His house was broken into twice; people defecated in the street in front of it, and prostitutes solicited there as well. It was also a time of active gang violence in the area, despite the famous truce between the nearby Venice 13 and Shoreline Crips a couple years before.5 At one point early on, it got so bad that he and his wife considered moving, maybe even buying the historic home of Venice’s founder, Abbot Kinney, which was then on the market in a nearby section of Venice referred to as “Ghost Town.”6In the end, though, they stayed, eventually watching almost every house on the block turn a profit. In 2003, the Pearsons sold the property for $850,000.

When Alexander purchased the home on Cabrillo Avenue almost 32 years earlier (for about $9,000, according to longtime Temple member Marsha Getzler), central Venice seems to have been in a similar position as it was when the Pearsons moved in—poised for gentrification but still remaining, for all intents and purposes, the “slum by the sea,” with plenty of dilapidated properties, drugs, crime, and a diverse demographic of people living there.7

Alexander was born in Chicago and grew up in a Jewish family in the West Adams neighborhood of Los Angeles. By 1968, he was 45 years old and had led a peripatetic, Zelig-like life, having been consistently involved in or at the center of some of the more exciting cultural moments of the previous 20 years in California. He met Wallace Berman as a teenager and together they hung around jazz clubs, befriending Charlie Parker and other musicians. In his early years, he wrote and published poetry, worked as a sideshow barker on the Venice and Santa Monica piers and later as a jazz disc jockey who went on to manage the colorful musician Slim Gaillard. In 1950, with his first wife, he opened a store in the San Fernando Valley called Contemporary Bazaar, which sold objet d’art and jewelry, and housed an extensive collection of small print publications from all over the world. The Contemporary Bazaar—from which Alexander’s most popular nickname, Baza, was derived—also held backyard readings and performances, namely by the comedian Richard “Lord” Buckley. It never succeeded in selling much merchandise, but at the time, it was one of the few establishments of its kind in Los Angeles. During this period, Alexander met artist Ed Kienholz when, by chance, he happened to stop in at Kienholz’s studio near the Bazaar on Ventura Boulevard. He acquired some of his first assemblage paintings to sell at the store, and the two became friends. Later, through an introduction by Alexander, Kienholz and curator Walter Hopps would go on to found the original Ferus Gallery. Alexander—who chose the name “Ferus” (the Latin word for “wild”) from a dictionary—printed and designed all the early invitations and posters. He shared a studio with Wallace Berman called Stone Brothers on Sawtelle Boulevard, where, under the tutelage of Alexander, Berman learned how to use a hand press and made the first copies of his magazine, Semina. Alexander also had a publishing project at the time, Press Baza.8

In late 1957, he left LA for San Francisco’s beat Mecca, North Beach, to work in a book warehouse with his former roommate Norman Rose and start another gallery, Dilexi, with Jim Newman (formerly of Hopps’s first gallery, Syndell). Like the Bazaar and Stone Brothers, Dilexi also had readings and performance events; and like Ferus, it initially served as a serious showcase for underground artists. Alexander stayed until Newman “went New York style,” as he told curator Sandra Leonard Starr in her indispensible oral history of the period. “A lot of the people that had been involved, a lot of the outlaws—the San Francisco outlaws—either lost interest in the gallery or Jim lost interest in them.”9

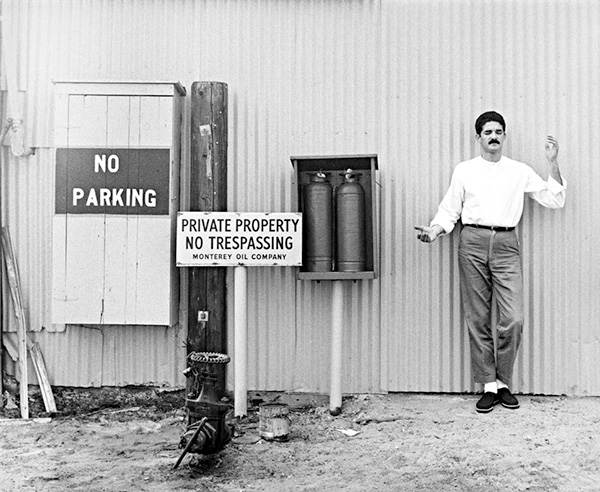

Tall, sinewy, and roguishly handsome, Alexander is most often pictured with a thick triangle mustache and big square eyeglasses, sometimes posing in various stages of undress—as in a wonderful photo taken of him alongside John Reed and John Altoon the day of the first Ferus opening (where, it appears, right before the shutter snapped, he decided to take off his pants). Despite his robust appearance in photographs, Alexander struggled with heroin addiction on and off throughout the 1950s, most likely beginning to use, as Starr writes, to self-medicate a manic-depressive condition. It might have been part of this struggle that led him to turn to theology at a Baptist church in San Francisco, the People Church, where, as Alexander later told a reporter for the Herald Examiner, he studied for two years and was ordained as a minister by the Reverend Melvin B. Johnson in 1959. That same year, he performed marriages for two longtime poet friends, David Meltzer and Tony Scibella. In 1960, with the help of Johnson, the Temple of Man was incorporated as a nonprofit.

Charles Brittin, Robert Alexander, ca. 1960. Courtesy of the Charles Brittin Archive, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. (2005.M.11)

As he later indicated in a memo to his ministry, it was surely also the work of Wallace Berman that initially inspired and led Alexander to the idea of the Temple of Man. Berman’s contentious 1957 show at Ferus (which ultimately led to his arrest by the LAPD) included a piece called Temple, a shack-like structure, the walls of which were painted black. Inside a figure stood with its back to the viewer, wearing a long white robe and an oversized key that hangs from the neck. Pages of Semina were scattered on the floorboards. The ambiguous scene, which seems to depict a type of personal sacredness and to connect religious imagery to creative output, is reflected in another tenet often used by Alexander and printed on Temple of Man material: “The Temple of Man is within.” Originally coined by Meltzer, the sentiment is reiterated in the Temple’s articles of incorporation, dated 1967: “The Temple of Man is formed in dedication to the sentient individual, creative man, and for the preservation of his creative works, in order to help broaden perception and increase the understanding between all men everywhere, who, being unified by the supreme force of life, are working toward a higher social and spiritual evolution.”10

“It is not worship so much as a quest,” the statement goes on. “It is a way of becoming, of liberation.”

Alexander never appeared to aspire to be a cult leader. Unlike Jim Baker, a frustrated actor who moved to Los Angeles from Ohio in hopes of playing Tarzan in film and instead went on to found the infamous Source Family, Alexander founded the Temple from a platonic ideal of what it meant to be an artist.11Alexander, like many of his contemporaries, including Berman and Herms, never put an emphasis on showing his work commercially. Their art was more often intended for their friends, or, at least, the work often used inaccessibility and temporality as part of its overall conception: Berman’s Semina gallery was located on a houseboat in the isolated marshes of Larkspur; Herms made and then abandoned his first major installation piece, Secret Exhibition, down near his home in Hermosa Beach—it is said to have been seen by all of two people.12As Alexander recalled to Starr, “After Dada, everything around us opened up. Everything blossomed like a flower, because we knew we could do anything. That made every creative act that said something a piece of art.”

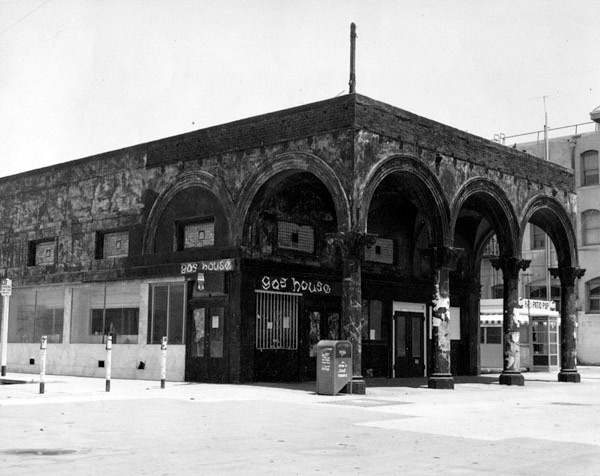

“The artist is what you are and have always been,” Meltzer wrote him in a letter when the Temple was long under way in the eighties. “One of a kind; the walking work.”13Perhaps Alexander had been disillusioned early on by his experiences at Ferus and Dilexi. He’d also watched other close friends, namely the poet Stuart Perkoff and artist Ben Talbert, be turned into caricatures of themselves and exploited by writer Lawrence Lipton in his tell-all 1959 book on beatnik culture, The Holy Barbarians. (“Help stamp out Lawrence Liptonism,” a 1962 postcard to the Los Angeles Times from the Temple of Man Fellowship reads.) Subsequently, after Lipton’s book and the brief surge of fad attention it brought to “beatnik” culture, Alexander witnessed the demise of a certain halcyon Venice—the end of the poetry café, Venice West; and the long battle and, finally, the demolition of the Gas House, once a type of commune where artists could live for free and the poet and Temple of Man member John Thomas worked as a cook. The crowds flocked and then dwindled, leaving Venice with beatnik as a dirty word in their wake.

Exterior of the Gas House, Venice, CA, 1962. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library.

In creating the Temple, Alexander was essentially reaffirming his own exclusive community, one whose membership only he dictated. A memo from 1981 says as much, though perhaps somewhat disingenuously: “So many people have asked us how one becomes a member of our organization. […] As of this date our bylaws have not been amended to include a general membership. If you have been ordained by our Temple you automatically become an Associate Member. Because of our continuing space limitations we are unable to house a general membership at this time. […] That’s the story!”14

Besides giving him a stake of ownership, it seems that the formation of the Temple also gave Alexander a sense of art for purpose, turning his idea of himself as a straight outlaw into an upstanding outlaw citizen. His archive at the Smithsonian reveals a charming mensch who prodigiously wrote letters of concern and complaint; an ongoing correspondence regarding a problem of poor mail delivery went all the way to Congress. He also wrote letters of curiosity—what was in China Gold Beer? had Select TV ever considered including adult movies in their programming?—and thoughtful letters praising people he encountered at the bank, in government, in the media whom he wanted to note were particularly good at their job.15In an addendum to the Temple’s initial articles of incorporation, a loopy manifesto called “The New Magic Theater,” which references Artaud and Genet, he defended his vision for a nonhierarchical (though, in fact, he would be the leader) collective, a cultural movement based on doing for others. “The tribal idea is certainly not new,” he wrote. “But the fact is that now, by spontaneous action, many people are beginning to structure their newspapers, their social gatherings, and their attitudes on SERVICE to others.”16

As he did, too. In its most active period in seventies, the house on Cabrillo provided one of the few consistent venues in Los Angeles, besides Beyond Baroque, for poetry and literary readings. It held free weekly yoga classes taught by former nun turned poet Philomene Long, staged open houses, and had a Temple thrift store in the garage. As Los Angeles magazine reported, Alexander married countless people at his home, most often in his hot tub, also for free.

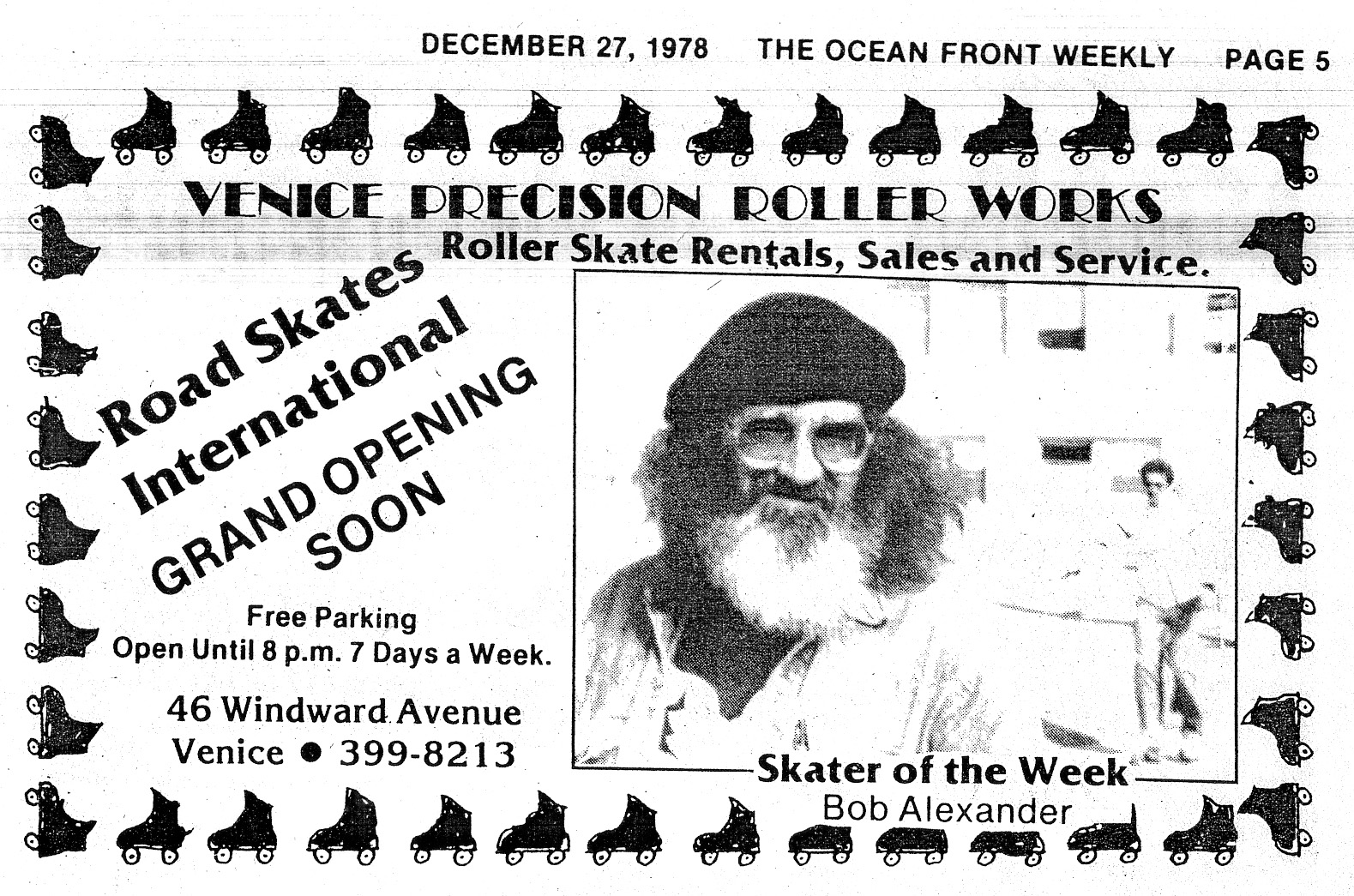

Bob Alexander, Skater of the Week. From The Ocean Front Weekly, December 27, 1978.

In many ways, these activities sound a lot like things that might happen in any of the proliferate, small artist-run spaces in Los Angeles today—but perhaps with a bit more irony. And as much as he became a stock Southern California oddity—the roller-skating minister of the Venice Boardwalk, advertising his hot tub weddings in the pages of WET magazine and sending out postcards with the hilarious slogan, “Laissez Les Bons Temps Rouler Within”—the Reverend Baza seems to have been a character whose persona Alexander was aware of constructing and eventually wanted to step out of.17

Toward the end of his life, Alexander wanted to open a cabaret space, as well as a serious museum and archive for the collection of Temple art and ephemera he’d amassed over the previous 25 years. Many of those artists were now gone, their names engraved in brass plaques attached to a shrine he built in his garden out of abandoned timbers from the old Ocean Park pier; the scraps of Venice’s past now buoying the dead of his clan: Stuart Perkoff, Ben Talbert, Artie Richer, Wallace Berman. Who knows if the bureaucracy involved in such ventures would have ultimately led Alexander to again seek a different outlet, one more aligned with the freedom he’d desired in starting the Temple of Man in the first place? Ultimately, he did not have time to find out. His collection is now scattered, though many of the artists whose work he strived to preserve have since gained recognition. The Temple of Man remains, as a smaller version of what it was before—a selective society forged by human connection, not institution—with 300 members worldwide, according to Getzler. It continues to intermittently publish books, stage events, and conduct marriage ceremonies. So, perhaps for Alexander, someone who seemed to vacillate between object and idea, a desire for stability and an attraction to the ephemeral, someone who once anticipated mainstream doubt and the criticism “that people are people and, well, you can’t build dreams on them, or even turn them on,” the fact that his legacy is still there, if obscured, accessible only to “certain people” and by the intervention of coincidence, is really just fine, after all.