In the Front Row for Chris Burden’s Match Piece, 1972

by Paul McMahon

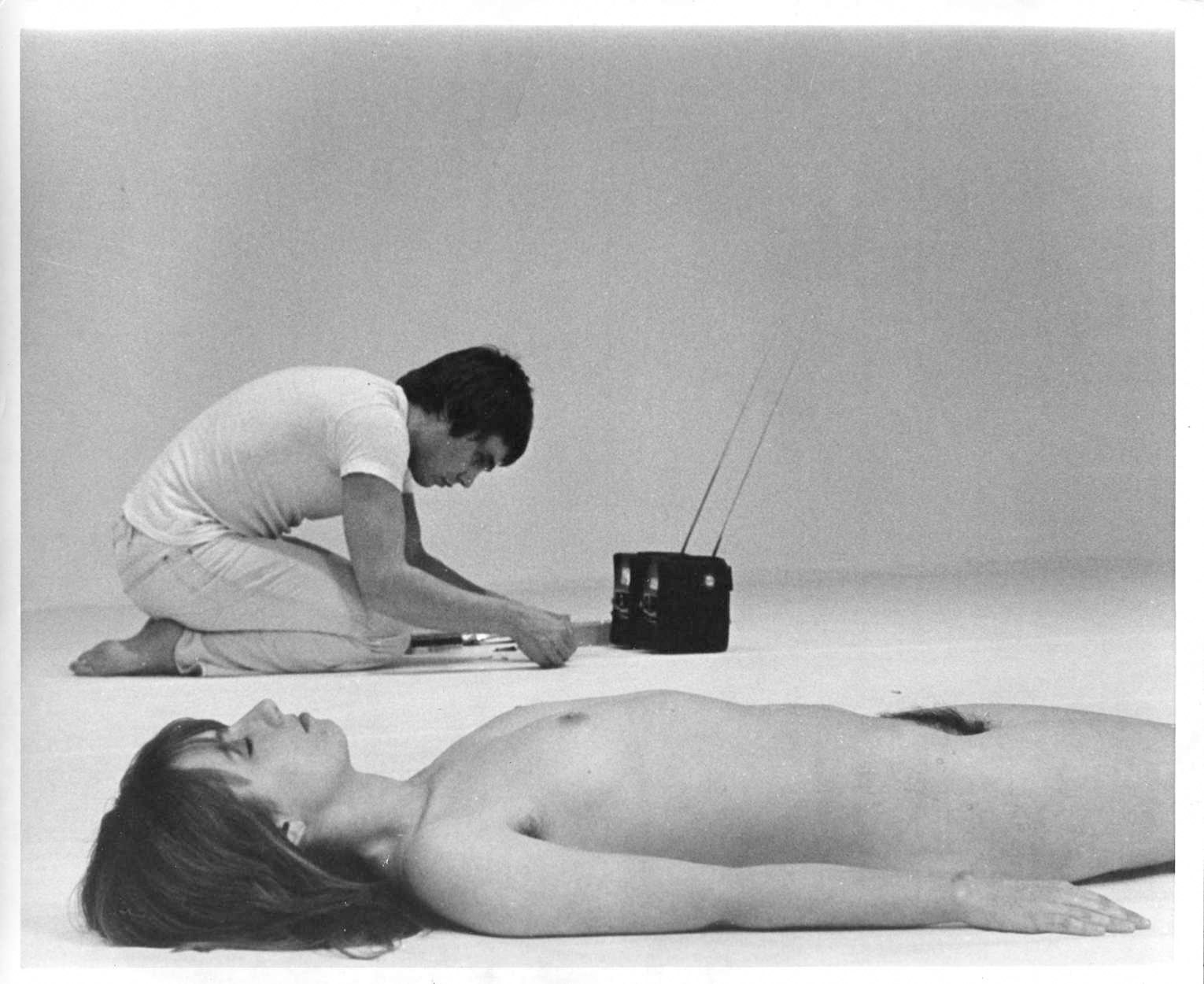

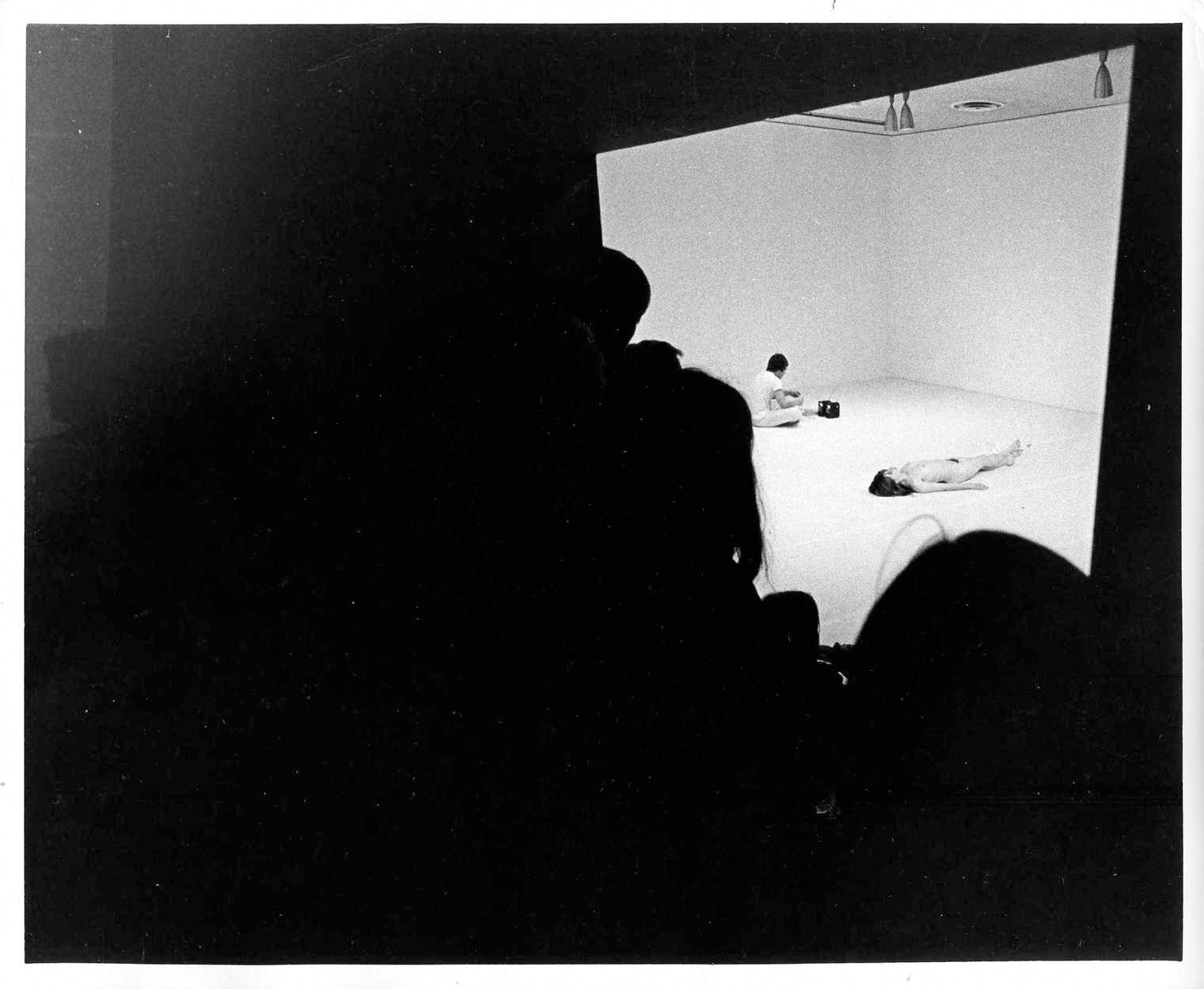

Chris Burden, Match Piece, 1972. All photos: R. Boss. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA.*

First-person accounts of performance, while subjective, offer a visceral record of action as it happens—especially valuable for ephemeral works. The following review of Chris Burden’s performance at the Pomona College Gallery on March 20, 1972, was intended for the student newspaper, The Collegian. The writer, artist Paul McMahon, was an undergraduate at the time. Burden, who graduated from Pomona in 1969, performed as part of a Monday night series featuring young artists from southern California organized by Pomona’s then-gallery director, Helene Winer. The gallery was host to many groundbreaking and experimental exhibitions and performances in the late 1960s and early ’70s, by such artists as James Turrell, Peter Shelton, Michael Asher, Judy Chicago, Ed Moses, Allen Ruppersberg, William Wegman and Wolfgang Stoerchle.—Eds.

Chris Burden’s performance took place in the large room on the right side of the gallery. Most of the floor was covered by white butcher paper, with a space near the entrance left for the audience to occupy. The whiteness of the paper, reflecting the whites of the walls and ceiling, created an all-white space. The performance began a little after eight o’clock and the activity of the piece got under way before the audience was allowed to enter. At that moment Burden was kneeling directly on the floor, with his right side facing the audience, toward the back of the space. He was wearing a white T-shirt, off-white Levi’s, no belt and bare feet. He stared intently at two tiny black, transistorized black-and-white TV sets that sat side by side in front of him. At least one TV was on throughout the whole performance, with sound. Burden periodically switched from one to the other, or had both going at once. The sound was quite loud. About ten or fifteen feet away, between him and the audience, a naked girl lay on her back with her eyes closed and hands at her side. As he watched the TVs the artist was wrapping aluminum foil around the heads of matches and heating them until they lit. The jet pressure caused by igniting the match heads shot them into the air, and he used a makeshift launcher made from two bent paperclips to fire these little missiles in the direction of the girl. The direction and distance the matches flew varied greatly and did not seem very accurately controllable by Burden. In all probability fewer than fifteen matches hit the girl. When hit by the hot matches she usually flinched, and when one landed directly on her she swept it off. The average range of the cardboard matches was about the distance to the girl while the wooden ones were more powerful and more difficult to control. Many of them misfired, but a few flew forcefully into the audience space. Because Burden prepared and fired each match separately the overall pace was very slow, about one match per minute. The artist at no time showed any interest in the audience or the girl. His face had the sort of unself-conscious and disinterested expression one might expect from someone who was alone. He looked calm and absorbed in what he was doing.

A closed-circuit television camera was positioned over the entrance of the gallery and the playback screen was on the wall behind the audience at about eye level. It showed only Burden and the girl on the white paper, the rest of the space was cropped out. The camera was only used for simultaneous playback; the performance was not recorded. The events on the screen were shown at the same time that they happened in the room. Because it was not recording, the video picture had the same duration as the live scene, which increased the similarity between the two, by making the video image as impermanent as the performance. A strong sense of separation existed between the performance area and the audience area. The whiteness of the paper and the artist’s outfit, combined with the emptiness of the large space, created a sense of sterility and purity because of the association with snow, hospitals, art galleries, etc. The small audience area was at times uncomfortably full of people, who talked and moved around and in and out of the space. The density and variety of colors of the floor, people’s clothes and accessories contrasted with the all white area. The video system helped underscore this alienating separation between the two spaces, for in order to look at the screen, the viewer had to turn his back on the live action. Turning back, he realized that he had no more personal contact with the live performers than with the characters on the video screen.

Chris Burden, Match Piece, 1972. All photos: R. Boss. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA. Complete caption below.

Burden ignored the audience. He acted as though he was unaware of the presence of others in the room. In this way he ruled out the possibility of direct personal contact between himself and the people in the audience. He also made himself inaccessible by keeping himself interested in other things. Every match missile flew a little bit differently, depending on how the foil was wrapped, suggesting that he was experimenting with them, since he made and fired each one separately. Throughout the performance he divided his attention pretty evenly between this activity and watching the two TVs. He was doing things that are absorbing and amusing to do, but very boring to watch. Most performances try to engage the immediate interest of the viewer, inviting him to become involved. But this show was an exception, as the artist closed avenues of audience involvement by minimizing visible actions, cutting off personal contact with the audience, and by making it clear that the activity would probably continue, unchanging, for quite a while. It was difficult to feel involved in the action in the piece because it was so inconsequential and boring, and this may have been more of a disappointment with Burden than it would have been with another artist, because of his notoriety. Many people had come to this show because they had heard about one or two of his more spectacular and violent performances—sitting in a tiny gym locker for several days and nights, having himself shot in the arm.

At about 10:45, with nearly the entire audience having left, Burden got up and walked out of the room to get the girl’s clothes. Rumor had it that the piece had been planned to continue until everyone in the audience left, and cutting it short in this way weakened it as a concept. Maybe the artist wanted to avoid a situation where the proposed duration was taken as a dare, with that last viewer intending to stay all night. If such a situation had developed it would have become unduly important and detracted from the piece’s meaning as a whole. Be that as it may, the proposed duration of the piece also served to separate the two spaces in that the whole time the audience was there the people from one space never physically entered the other one. The audience never saw Burden and the girl outside of their performance roles. There was no friendly mixing with the audience afterwards in the front room of the gallery as there had been at the other two shows. This overall psychological and emotional distance and lack of involvement between the two areas was reflected by the audience in that people did not feel many inhibitions about acting very informally. People talked, joked and moved around freely from quite early on in the performance. The fact that the piece was hard to get involved with, combined with the loudness of the TVs the artist was watching, made it natural for spectators to start talking among themselves. Because the show was frustrating and hostile to the audience, people had common feelings to talk about. There was more talking between strangers at this performance than at the other two.

Burden rejects the traditional idea of the spectator’s being a passive onlooker who sits back and watches the show. Entering the room in which the performance took place, the viewers were made to feel they had intruded on the artist’s personal space and privacy. And by ignoring them, Burden increased the tension, making them feel either unwanted or unseen. This show eliminates the spectator’s neutral detachment, meaning that a disinterested judgment was possible only after experiencing the unpleasantness of the piece firsthand, and being offended and frustrated.

Throughout the show Burden looked calm and contentedly engaged with his activity, not unlike a child at play. With his short hair, T-shirt and bare feet he looked very boyish, and this childish appearance, along with his obvious acceptance of what he was doing, linked what we think of as the innocence of the child playing out a scenario of domination that in some ways resembled a sexual control fantasy. He was inflicting a painfully and covertly sexual ordeal on a good-looking naked woman over whom he appeared to have complete control. He further denigrated her by not paying very much attention to her, as he watched the TVs and made each match missile. The acting out of the fantasy was disturbing in that Burden was openly admitting that he derived pleasure from dominating another person. The use of sexual fantasy, because of its universality, made the inescapable point that we all get satisfaction from dominating others.

Along with the disturbing personal questions raised by the acting out of the fantasy, the performance as a whole was basically unpleasant for the viewer. It created a hostile environment. Burden achieved a very present sense of alienation. Those things about the piece that were not unpleasant—the white paper and the video system—were relatively neutral. The only direct contact Burden made with the audience was firing a few matches into it, a hostile gesture, used to remind the spectator that he was in the same room as the artist, reminding the viewer that he was an intruder. It also made the statement that the artist wanted the audience to leave. The proposed duration also implied this, by making the performers stay until all of the spectators left. Other elements of the piece, its private and boring nature and the artist’s obliviousness to the audience’s presence, support the statement made by firing matches into the audience space.

Chris Burden, Match Piece, 1972. All photos: R. Boss. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA. Complete caption below.

For me this piece was an unpleasant experience at first, until I started getting interested in the separation between the two spaces and in the idea that the act of trying to be a spectator became an invasion of the artist’s privacy. Art certainly does not have to be hostile to the viewer, but being hostile does not necessarily keep it from being good as art. Burden created a very interesting situation. I especially liked the image of the video playing back in real time, but not taping. It was also interesting in the way it came close to being theater without becoming theater; the way the spectator was not allowed to be passive and the fact that audience interest should determine the piece’s duration. I ended up liking the show as art, but I found it hard not to resent personally aspects of the experience.

*Full caption for above images, by Chris Burden: “Two-thirds of the gallery floor was covered with white paper. A closed circuit television system was installed in the room. The monitor was placed so that the audience could watch the piece or see it in the monitor, but could not do both at once. I sat on the floor at the opposite end of the room. Two miniature TVs were placed so that I could view them while I made match rockets and shot them at a nude woman lying on the floor about fifteen feet from me. The rockets were made by wrapping the match head with foil and igniting it with another match. Range and accuracy were impossible to control. Some of the rockets landed on her body leaving small burns, others landed in the audience. The piece began before the audience arrived and ended when everyone had left, lasting about three hours.”