In the Valley with Jeffrey Vallance

by Damon Willick

Jeffrey Vallance, Meeting with Little Oscar and His Giant Wienermobile, ca. 1973. Performance in Granada Hills, CA.

Situated between the Santa Susana, Verdugo, and Santa Monica Mountains, the San Fernando Valley encompasses the northwest section of Los Angeles. With a current population of close to two million “Vals,” it is home to more than one-third of the city’s total inhabitants. Vals have long been outsiders to the cool school of LA mythology. Predominate views of the Valley reek of cultural elitism and classism and cast the region as ground zero for all that is detested about Southern California: suburban sprawl, smog, porn, mini-malls. Bad taste, however, is not the same as no taste, and there is a significant art history of the San Fernando Valley that is worth exploring in relation to Los Angeles’s broader development as a contemporary art center.

Jeffrey Vallance lives in Canoga Park, not far from where he grew up. He has spent much of his life in these parts and has been described by Dave Hickey as the Valley’s Herodotus and its Candide. As Hickey writes: “For him, the Valley, and the Valley world that spreads beyond it, is the domain of real fakes and fake realities, with no center, no edges, no top, no bottom, and no direction—a tattered sphere of overlapping neighborhoods and floating islands, where everything is interconnected, always interconnected, everywhere.”1But Vallance’s relationship with the area is complex. On the one hand, he sees the Valley’s ersatz architecture and cultural amnesia as regrettable; yet, on the other, the Valley has supplied the material and motivation for his pranks and conceptual activities.

The following conversation took place over coffee and eggs at the Canoga Park bowling alley.

DAMON WILLICK: The Valley has been described as many things by many people, but how would you characterize the place?

JEFFREY VALLANCE: There is a uniqueness to the Valley, but it’s constantly changing. It went through a Polynesian phase, for example, when apartment buildings and bars were decorated with tikis. Some of the apartment buildings still exist, but by the nineties, tiki was totally out and they tore all that Polynesian stuff away. The buildings are still there, but they don’t make sense anymore because they have these high-pitched Polynesian roofs but are now painted plain brown without any sort of decoration.

I’ve seen these fads come and go in the Valley. There was an Old English Tudor phase and plenty of other revivals, but they are all fakes, you know? It’s a lot of stealing from other cultures. This happens throughout LA, but I think it’s more intense in the Valley. And there are certain things about this building and rebuilding that make me really mad. Like, we’re sitting here in this nice coffee shop, and I love these types of diners, but I’ve seen developers tear down so many authentic Valley diners only to replace them with fake ones. They’ll build a Cafe 50’s or Mel’s Diner, and people stop going to the real one because it’s old. But you build one that looks old, and they will go to that.

Jeffrey Vallance, Avenue of the Absurd: Aku-Aku Motel, Woodland Hills, CA., 1985. Ink on paper. Originally published as “Mr. Vallance’s Neighborhoods: The West Valley Revealed in Words and Pictures,” L.A. Weekly, Sept. 20, 1985.

I think that’s the history of the Valley. Everything disappears—every scrap of history, every historical building, every monument, every field, every tree—and the process is still happening. About a block away, there is an old farmhouse that must have been one of the original structures when the area was agricultural, and it’s being demolished. Most cultures want to preserve their pasts, they like historical buildings and their history, but the Valley and Los Angeles love to seek out old things and tear them down.

DW: It’s amazing how true this is. Many of the buildings you included in the Avenue of the Absurd drawings from the mid-1980s, for example, are no longer there. Even the fakes get replaced eventually.

JV: The Batman-a-Go-Go’s gone. The Jehovah’s Witness hall is no longer there. The Victorian and the Moorish buildings are still there, though.

DW: How does your art practice relate to such an area?

JV: I should explain that I’ve always made two kinds of work. I was actually trained as an artist by my grandfather who was a Norwegian folk artist. So the first thing I learned was how to make folk art, and that has always influenced my work. Sometimes people think that I am using a fake folk art style, but it’s really not. That’s how I learned to paint. At the same time, I was into doing pranks, which were really about interacting with my environment and people that I’d see—government officials like Mayor Yorty and Mayor Bradley but also corporate logos and characters, Ronald McDonald, Jack in the Box, Little Oscar from Oscar Mayer. I think that there used to be more of those that would show up for openings of supermarkets and hand out stuff. Every time that any of those personalities or characters would appear, especially a corporate one, I always wanted to go and have some strange interaction with them. I didn’t consider it art; I had no label for it. It just was what I wanted to do, and it’s what I did with my time.

DW: How old were you when you first started to document these pranks?

JV: I was in junior high school, maybe 13 or 14.

DW: The fact that there are photographs of your posing with the Oscar Mayer wiener mascot as he made promotional appearances around the Valley makes it more than just a prank. How did you have the foresight to document some of these things?

JV: That was the prize. People wouldn’t believe you if you didn’t have a photograph or if you didn’t have some document. You had to have proof. I think it was the only reason I saved the things or took the photographs. It was evidence for storytelling because it was like, “I did this crazy thing, and here’s the photo, or this is what they gave me, or here’s the letter.” Otherwise, people would think that you were making up the whole thing, and I have learned that a lot of people still think that all these things I’ve done are fictional, that I couldn’t have possibly done them.

Jeffrey Vallance, A Tribute to Oscar Mayer, 1974. Mixed media.

DW: I remember being a kid growing up around here, and there were always a lot of mischievous characters. Do you think that you would have been as mischievous if you grew up outside of the Valley?

JV: Maybe, but I wouldn’t have had access to all these stage things, you know? I wouldn’t have had access to Hollywood, to these corporate mascots. I guess I would have had access to other things—like, if you lived in an agricultural area, you’d overturn cows or do other kinds of pranks.

DW: But your jokes were never malicious; you weren’t driving around smashing neighborhood mailboxes—

JV: No, they were devious, but they were good-hearted at the same time. They were so convoluted that they couldn’t really make you mad because they were hard to figure out. It wasn’t about destroying something; it was more like adding something or interacting with people. I love to create random elements in strange contexts that people then have to deal with.

DW: And you were always open to being caught, too. Like with the Oscar Mayer mascot coming over and asking if you wanted to ride with him to his next appearance.

JV: He said, “Since you’re going to show up at all the supermarkets, you may as well just come along.” And that was perfect. I’ve developed that attitude over the years, and it is part of my work. I like to push people as far as I can possibly push them without making them upset, and then I often include them as part of it. I think when you include them you have this totally insane situation, but at the same time you are diffusing any negative aspects. It’s like my project of rewriting the Bible [The Vallance Bible (2011)] and asking theologians to give me their opinions on it. They can say whether they like it or not, and whether I’m correct or wrong. It diffuses the situation and allows them to be happy about being abused.

I think that is the crux of the whole thing: Everything I see, I have to mess with. Like, anything that appears in front of me, whether it is a politician or religious figure, it’s all fodder. Part of that is about trying to learn and get on the inside of something to see how it operates. Also, I like to see how far I can push things. A lot of people that I’ve dealt with, I’ve dealt with for years. There are these ongoing projects that I keep working on with the same people and just keep on pushing them farther and farther.

DW: At what point did this start becoming “art” for you?

JV: Yeah, that was an interesting moment. I started doing these things in junior high school and more heavily in high school. By then, all I knew about art was Salvador Dali and the Surrealists, and that was as far as I got in art history. When I went to Pierce College in 1974, I showed a professor all of my documentation of the pranks—these photographs, Frisbee with Sam Yorty—and he looked at them and said, “This looks like Conceptual Art.” I didn’t even know what that was.

So I didn’t know that what I was doing could be art. It was just something that I did. After that recognition, this lightbulb went off: “It’s all art!” All these things—the pranks, the letters, the interventions—all this stuff was art . It was wonderful. It made my life make sense.

Jeffrey Vallance, L.A. City Hall Frisbee Throwing Spectacular. Performance with Mayor Sam Yorty, Larry “Seymour” Vincent and Mr. Blackwell at Los Angeles City Hall on Jan. 20, 1973.

DW: When you realized this, did you study conceptualism and performance?

JV: I just continued what I was doing. There was one point where I really loved reading art magazines. Every time a new Art in America and Artforum came out in the library, I was there the first day and just ate it up completely. That was when Chris Burden was first performing, and I just loved his work; he is one of my major influences. Although I wouldn’t consider myself a body artist, I liked his outlook on everything. I didn’t do a systematic study of Conceptual Art and didn’t take in all the trappings and the jargon. I just continued to do what I was doing. As a result, I think my art lands in a gray zone and still remains confusing to people, because it doesn’t have all the watchwords of conceptualism and does not exactly fit into any particular movement. I’m just slightly outside it all—my performances are not performances, my Conceptual Art is not Conceptual Art, and my paintings are not paintings. You can’t recognize any of it, so it can’t be placed anywhere, which is either a major blessing or a curse. It depends on how you look at it.

DW: How was studying at California State University, Northridge, as an undergraduate?

JV: Every place that I’ve studied, even back to high school, seemed to be having, like, a high cultural moment. There was a moment at CSUN in, like, the mid-70s where it was a place for real art. You had an incredibly active faculty: Robert Smith, who was running LAICA [the Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art]; you had Karen Carson, Peter Plagens, and all these important art world characters. It was really CSUN’s moment. For some reason, it attracted these very interesting people in the seventies, and I just fell into it. It was a total accident, but it was wonderful.

DW: Let’s talk about your involvement with Michael Uhlenkott and World Imitation magazine at CSUN.

JV: The idea of the magazine was mostly theirs [Uhlenkott, Steve Thomsen, Anne Connor, and Laurie O’Connell]. It was collage-based, and they invited me to contribute weird, scratchy drawings that didn’t look like their collages at all. I was also involved in their band, Monitor, too. I helped on the album covers of their first 45s and their LP, did drawings for them, and sang with the band one time. But I was really more in the shadows.

DW: Even though you say that your work was dissimilar to theirs, did you identify with the early LA punk scene that they were a part of?

JV: Yes and no. I mean, I hung out with all the punks. I went to all the clubs and knew all the bands, but I was in a preppy phase then. I had the completely wrong outfit: a little sweater with a tie and a nice haircut. I just looked like some preppy college kid, which people didn’t do then, so I was totally wrong in that environment. I remember punks would really get mad at me when they would see me at the shows because I just didn’t look right. I did it on purpose.

Michael Uhlenkott and Jeffrey Vallance painting cows on the roof of CSUN, 1977.

DW: I recently spoke with Michael Uhlenkott, and he talked about the first time you guys went to the Masque in Hollywood and having nightclub owner Brendan Mullen say something like, “Go back to the Valley and get haircuts. You can’t come in here looking like that.”

JV: That seems about right, yeah. There is something important about always being wrong.

DW: This brings up an interesting point about the wrongness of Valley culture. There is a culture, but it can easily seem like one of blankness or blandness.

JV: The Valley is part of Los Angeles, yet somehow it’s like the worst or most embarrassing part. It’s the part where culture is not supposed to come from. Nothing is supposed to come from here. But maybe that is important. I used to say that I did my best work when I was completely bored because I would be so bored that I would have to invent something to keep occupied. Like, I’d sit around and think of something insane and go out and do it. And maybe the Valley encourages stuff like that. It’s so bland; it’s so nothing that you have to invent these fabulous things to keep yourself sane, because if you actually looked around the Valley, you’d want to kill yourself. Most of what I was looking at in art, even though I lived in the Valley, was over the hill on the west side or in Hollywood. I think there was one Valley gallery, but I forget its name.

DW: There was the Orlando Gallery.

JV: Orlando Gallery. Yeah. I went over there once with my work, and they turned me away. I decided that the Valley was only good as a pallet. It was good as a place to do pranks and set up stuff, but you didn’t want to have a real show here. You wanted to show in the world beyond.

DW: Dave Hickey has characterized the Valley as a place “where authenticity comes to die.” You’ve mentioned how you’ve used the Valley as inspiration, and I wonder if its lack of authenticity, per Hickey, is necessarily a negative.

JV: Hmm. It’s interesting. When I travel beyond the Valley or live in other countries or cities, I always end up in their equivalent of the Valley. When I moved to Sweden, I ended up in the Artic Circle near Lapland. Lapland is a part of Sweden that the Swedes don’t really like, but I was really into it. I spent some time in Tasmania, which is sort of like the Valley when compared to mainland Australia. So maybe it has shaped my way of thinking, of always seeking out these cultures on the edge of something rather than going straight into Hollywood or going to live in Manhattan. I’d rather live on the outskirts. There is something that doesn’t appeal to me about the mainstream of culture.

DW: It’s easy to dismiss it as that place where authenticity goes to die and the mini-mall reigns, but the Valley encompasses about one-third of the city’s population; and, when you live in LA long enough, you realize that maybe the entire town is just as inauthentic and mini-malled. I have a theory that the Valley is the id of Los Angeles. It’s the city’s uncontrollable self that needs to be suppressed.

JV: And Valley culture is spreading. I remember when I was a kid a lot of places didn’t look like the Valley. But at some point around the time of Frank Zappa’s song “Valley Girl” [1982], Valley slang spread to all of these other suburban pockets. I would go to some place, like, in Wisconsin, and all of a sudden they were speaking Valley talk and had mini-malls that looked like authentic Valley ones. It was like Valley culture was spreading across the whole world. I’d even see it overseas—parts of England have a weird version of Valley talk. Maybe this is the future, and everything will become this.

DW: Does this have to be a negative? Maybe the region’s supposed vulgarity can lead to a more populist or inclusive view.

JV: This is a very important idea. Maybe it was the way I was raised, or maybe it has something to do with the Valley, but the artists I’ve always liked—even back to when I knew very little about art—they were all well-known cultural figures, like Dali or Warhol. Everybody knew their names—any neighbor would know Warhol, and they would know Dali. But now I think that 99.9 percent of people cannot name a living artist. It’s as if artists have lost their status in culture or at least lost their influence on the culture.

I’ve tried to be part of our culture. I did Letterman; a lot of people saw that. I had my own show on MTV, and you can’t believe the popular magazines that I’ve been in. But because this exposure is outside of the art world, I have a hard time in the art circles. The art world today does not want to be accessible. It wants to be a private club with a secret handshake and a secret language, like a Masonic ritual; it’s secretive and exclusionary. The art world doesn’t want normal folk to be able to understand or enjoy art. But I have consciously tried not to be that way by dealing directly with mass media. I think that has closed certain doors to me. Art world people will often say to me, “Oh, I’ve never heard of your work,” even though I have been exhibiting for over three decades. Maybe it’s no wonder, as I’ve purposely focused my attentions on all the wrong venues.

DW: Yet you’ve published books [see The World of Jeffrey Vallance (1994), Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth (2004), Relics and Reliquaries (2008), and The Vallance Bible (2011)] and have written for many “insider” art journals. How do you see your writing in relation to your visual art?

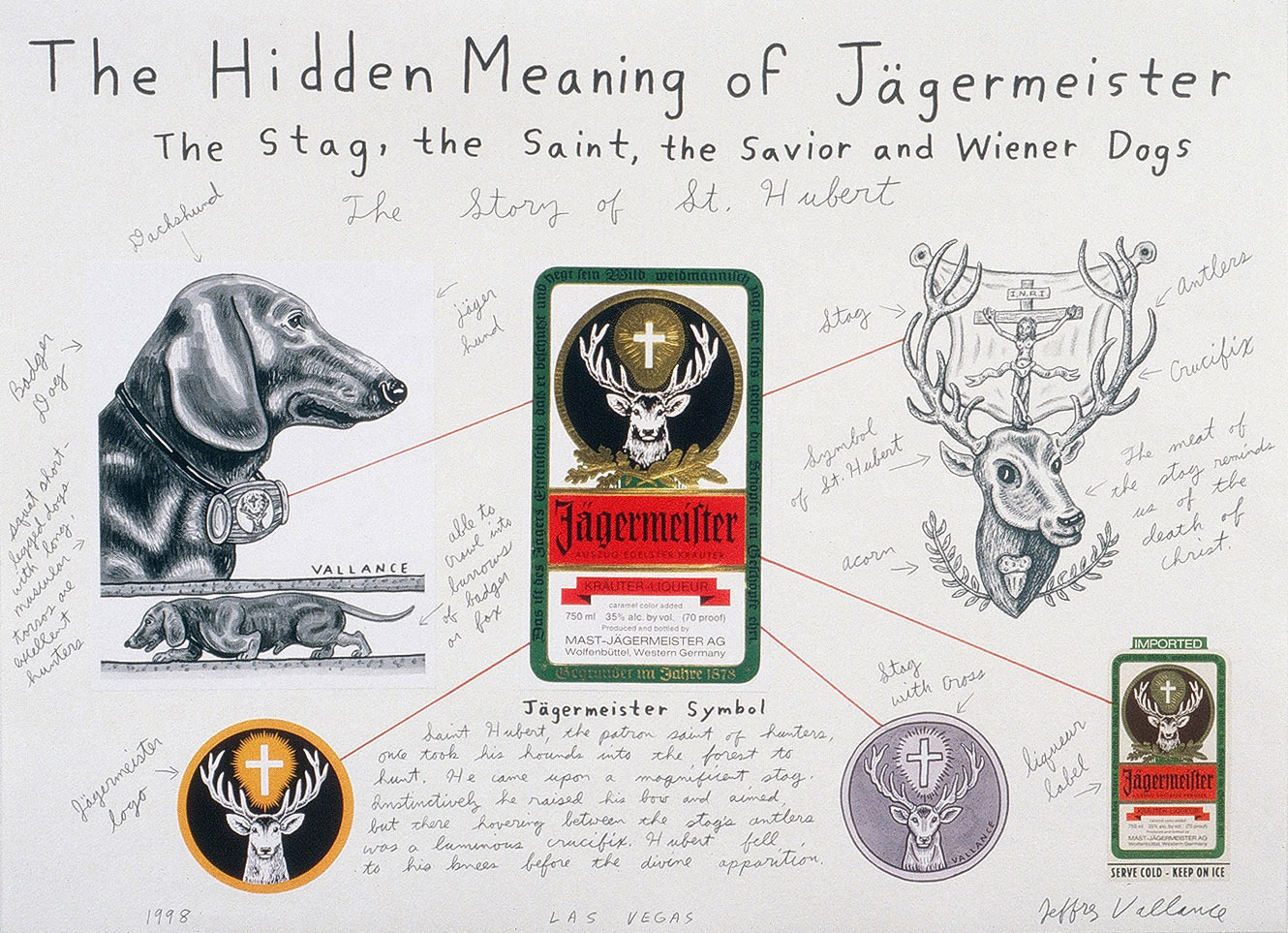

JV: I used to write for Art issues and L.A. Weekly. I rarely wrote about art, though. I would usually focus on cultural oddities that I found interesting. I wrote about the legend of Jägermeister, the origins of Santa Claus, Bigfoot, and the ghost of Nixon. I never mentioned art, but somehow my writing got categorized as art writing because I was an artist. Now I mostly write the same sort of articles for a paranormal magazine, Fortean Times. What I wrote for art magazines are the same things I write for the paranormal magazine, which is really funny.

Jeffrey Vallance, The Hidden Meaning of Jagermeister The Stag, the Saint, the Savior, and Wiener Dogs, 1998. Mixed media on paper, 22 x 30 inches.

The paranormal magazine publishes pretty much anything I write, even if it isn’t quite paranormal. When I wrote for art magazines, I never wanted to take on the art world jargon. I just felt opposed it. I was also opposed to taking up anyone else’s theory about art. I always want to have my own ideas, my own language, my own theory. I don’t want to borrow French theory piecemeal and put that in my work.

DW: There does seem to be an attitude among Valley artists—I am thinking here of artists like of Scott Grieger, John Divola, Mike Mandel—that is a type of serious unseriousness or rather, serious art that doesn’t necessarily take itself so seriously.

JV: Yes, but my work gets misread as simply “funny” or “comical.” A lot people can’t see past the humor, so it stops them. That’s in there, don’t get me wrong, but it’s only the surface. Once you get past the comedy, my art is really twisted; it’s about getting away with murder, about infiltrating systems. It’s about perversion. It’s like perverting everything around you in a seemingly harmless way.

My theory—and maybe this is a Valley theory, too—is that everything in life has something strange about it. There is something odd, even comical, in the events of our lives, even in its horrors. Like funerals: Funerals are very serious, but you’ve heard over and over again that for some people they have to stifle laughter because it is so serious that they can’t stand it. It becomes comical even though it shouldn’t be. So I really pick up on this idea that every reality has multiple layers—life has a comical part, it has a serious part, it has a sad part, it has a depressing part, and it has all of those parts at once. I feel like art should encompass this complexity. I want to make art that has all those layers, comedy and seriousness and death and everything else. The comical element sometimes stops art world folk in their tracks, and they can’t get beyond it. But for me, that’s not how life is. Life is continually all of those elements, all of the time, all at once.