Inside and Outside at the Same Time

by Karin Higa

This essay was originally published in The Sculpture of Ruth Asawa: Contours in the Air, ed. Daniell Cornell (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2006), in conjunction with the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. It is reproduced here with permission from the publisher. All original formatting has been preserved.

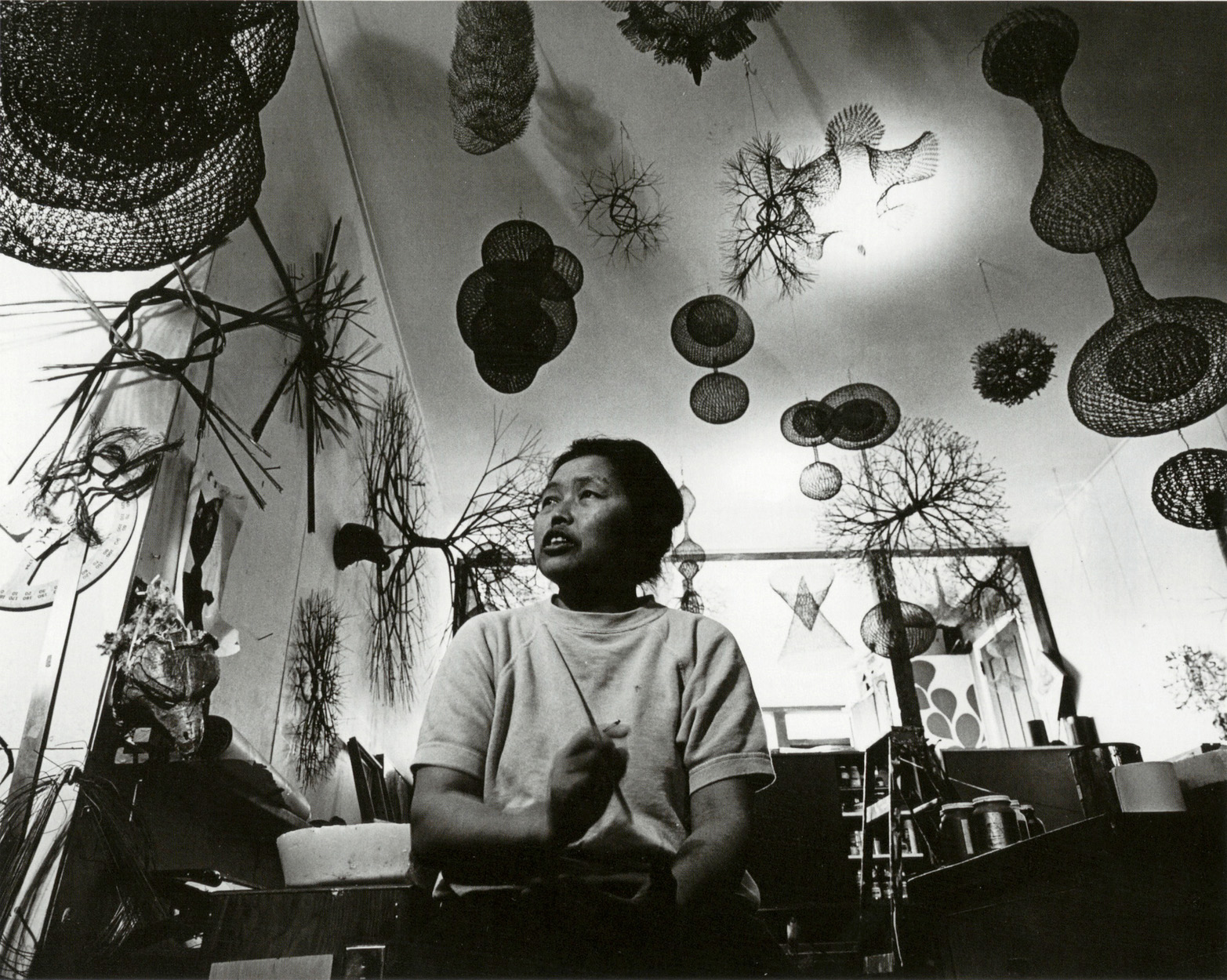

Ruth Asawa at work, 1957. Photograph by Imogen Cunningham. © 1957, 2014 Imogen Cunningham Trust.

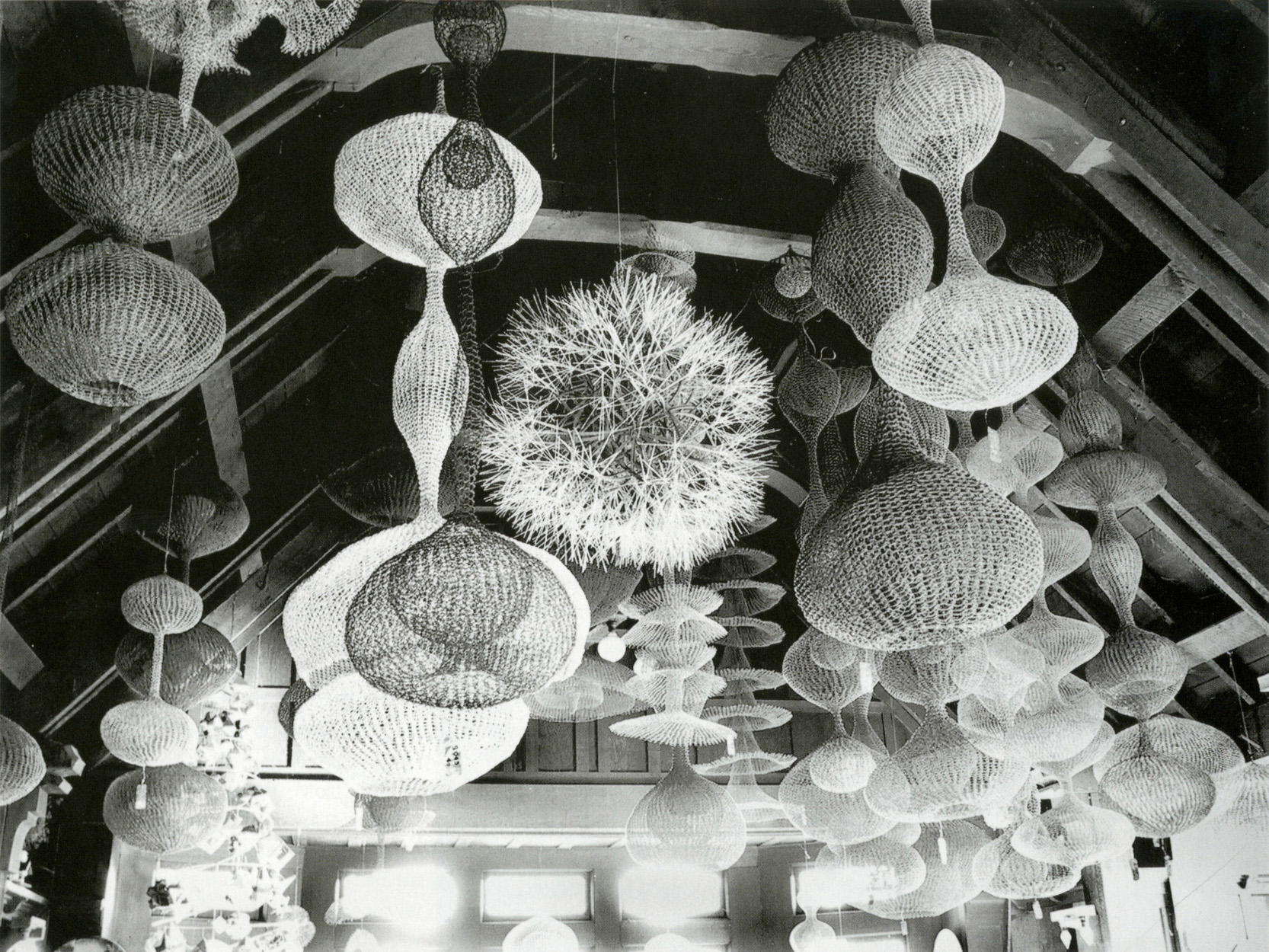

Exploring the exterior surface of Ruth Asawa’s looped-wire sculptures can be a tricky feat. As the eye grasps and follows the volumetric form, the exterior becomes the interior. Just when the mind adjusts to this switch, the interior transforms into the exterior again, the sculpture’s undulating form suggesting a continuous movement from one state to another without interruption. As Asawa once described it, “What I was excited by was I could make a shape that was inside and outside at the same time.”1This duality comes not from a transformation of the material, as the basic character of the metal wire remains the same throughout the sculpture. Nor does it derive from a dramatic manipulation of the looping process, since a simple chain stitch of evenly formed interlocking loops is employed. Rather, Asawa creates a dynamic sculpture by bringing a different approach to a conventional form of needlework and the prosaic material of wire. Like a paper Möbius strip, which is one of its inspirations,2an Asawa wire sculpture has no front or back or inside or outside. “You could create something … that just continuously reverses itself,” Asawa has said of this work.3

Understanding the significance of Asawa’s Japanese American identity to her art presents a similar feat. Almost all accounts of her art and life remark on the fact of Asawa’s Japanese heritage. From her earliest exhibitions to her most recent public art commissions, her ethnicity is evoked as if it could unlock both the meaning of her work and the origins of her experiences. Yet being a Japanese American has meant different things at different junctures to the conditions of Asawa’s art-making and the contexts of her art’s reception. While it may be impossible to assess what Japanese ancestry means to Asawa—her specific subjectivity—there is no question that her race and ethnicity mattered to others and presented unique circumstances that impacted opportunities for her as an artist just as it affected the way her art was received and interpreted. This essay proposes to briefly explore Asawa’s early life and art as a way to understand how her formative experiences as a Japanese American shaped her sensibility as an artist.

Asawa has repeatedly located her transformation as an artist to Black Mountain College and her principal teacher, Josef Albers. Of course, this is not surprising. Both Black Mountain College and Albers occupy a pivotal place in the annals of American art, and their impact has been explored in numerous exhibitions and publications.4But without minimizing the catalytic effect of the Black Mountain experience on Asawa, a number of factors present on her parents’ farm and during the family’s World War II incarceration cultivated in her the requisite conditions to fully integrate the philosophy and teaching of Albers and others at the college, namely: a familiarity with self-contained communal environments, requiring collaboration and toil; an appreciation for ingenuity through thrift; and exposure to progressive education that included sustained relationships with working artists. Asawa’s Japanese American ethnicity framed these experiences; while it may have condemned Asawa and her family to limited spheres of existence, it also opened up other avenues of opportunity, ones that ultimately enabled Asawa to pursue her specific kind of art and art activism.

Ruth in her studio, CA. 1970. Photograph by Rondal Partridge. © 1970, 2014 Imogen Cunningham Trust.

Life on the Farm

In a 2003 interview with her eldest daughter, Aiko Cuneo, Asawa describes the meager surroundings of her childhood home: “We didn’t have [art] on the walls. We had only one book, which was an encyclopedia, and we had a Bible.”5What Ruth did have was an extended family of Asawas. Her father Umakichi, his older brother Zenzaburo, and an uncle had established truck farms in Norwalk, California, after adventures working on the sugar plantations of Hawaii, in coal mines in Mexico, at a general store in EI Paso, and on farms in Utah and in Huntington Beach and San Diego, California.6The Asawas’ relatives in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, arranged marriages for the brothers, which were consummated through the exchange of pictures. In a practice quite common in the period, two sisters of the Yasuda family, Shio and Haru, married Zenzaburo and Umakichi, respectively. The families were doubly connected by blood and further tied to one another when Zenzaburo died, leaving Umakichi to assist in the care of his brother’s family of six.

On the farm—on leased land, as Japanese were barred from owning property—communal labor was central. The seven Asawa children were expected to contribute to the rigorous work schedule. Upon returning from school in the afternoons, they worked until dinner, after which they worked some more. Each child had specific duties but understood how it related to the whole. One of Ruth Asawa’s jobs was repairing the thin wooden boxes used for tomatoes, radishes, cabbage, cucumbers, melons, celery, lettuce, beans, and other crops.7Though mundane, the task required manual dexterity, the use of a hammer and hatchet, and the ability to gauge the width and depth of pieces of wood. To cultivate Kentucky Wonders, Blue Lakes, and lima beans, Asawa’s father used recycled laths to form the beanpoles, to which Ruth coiled string in a way that mirrored weaving techniques.8

Modesty and thrift, filtered through ingenuity and creativity, were evident throughout the farm. Built by Umakichi, the family home was a simple board-and-batten house with an interior of paper walls and a paper ceiling topped by a tin roof. “My father used to save every nail,” Asawa recalls, “and straighten them out.”9Even the family’s bath water was reused. Since Asawa did not like housework, she was assigned to tend the fire for heating the traditional Japanese ofuro, or bath, which required chopping wood and making sure the water was hot until the last of the family members took a bath—sometimes as late as 10 p.m.10When it was time to germinate seeds, the used bath water was the perfect medium to facilitate sprouting.11On the farm, maximizing the limited resources was central to the family’s survival. Every element was scrutinized so that it could be utilized for multiple ends.

Japan loomed large among the Asawa clan. Like many immigrants from Japan, the elder Asawas intended to return to Fukushima. They regularly sent money to Japan and amassed property and houses in the town of Koriyama for their future return. To prepare their American-born children, many Japanese immigrants set up Japanese schools in the United States, promoted Japanese activities such as the martial arts, and sent their children to Japan to be educated.12In Norwalk, the elder Asawa men were involved in the organization of the Japanese school, where the Asawa children were duly required to spend their Saturdays. Beginning with traditional group exercises and hearty shouts of banzai to the emperor, the school duplicated as much as possible Japanese practices. Discipline was valued, as was submission to rote forms of learning. Calligraphy, taught as the equivalent of penmanship, began not with free expression but as a codified set of repetitive lessons. Corporal punishment for inattentive students was the norm.

Although Asawa did not enjoy Japanese school, she—along with her older siblings—readily took to the study of Kendo. Literally translated as “the Way of Sword,” Kendo is a form of Japanese fencing that emphasizes the development of inner character married to skill and physical strength. Long associated with the samurai ethos of the elite class, Kendo was believed to embody the “spirit of Yamato”—the essential characteristic of the Japanese people. Although participation required a relatively large outlay of money for the special masks, gloves, guards, hakama, and bamboo swords, beginning in the late 1920s Japanese immigrant parents saw Kendo as a means to transmit essential Japanese values and promoted the sport throughout California.13Umakichi was a local leader in the Kendo community, which encouraged practice by both girls and boys. For Umakichi and other Issei men, Kendo provided a tangible framework to convey Japanese philosophy to their children. As one community leader wrote in the San Francisco newspaper Nichibei Shimbun, Kendo allowed the Nisei to “get their mind and body purified, and make the virtues of propriety, benevolence, humanity, and filial piety fully understood.”14A subtext was preparation for a return to Japan. But many Japanese Americans like Ruth and her siblings negotiated the dual life of allegiance to Japan and total assimilation into an American ideal with ease, transitioning from one state to another seamlessly. For Asawa, loyalty as a general concept was the issue. “We were loyal, so it didn’t matter who it was to.”15

Progressive Education

While daily life was characterized by the never-ending labor of a small farm, shifts in public education provided children with access to innovative models of pedagogy. Progressive educational reform took hold in California in the 1920s and 1930s as adherents increasingly saw the schools as centers for reform and socialization as well as a force for democratization.16Universal education also meant that the local public schools sustained a remarkably diverse student population despite the financial strain of the Great Depression. While Japanese and Mexican Americans faced institutional barriers to jobs, property, and social access, the public schools were a more egalitarian arena. This is not to suggest that schools were free from prejudices or the effects of racism. However, as nonsegregated places of social interaction, they provided an opportunity for children to experience and interact in a broader context.

Ruth (front row, center) in Ms. Fain’s class, 1935

One effect of educational reform was the decentralization of decision-making from the political apparatus of the state to local superintendents and administrators.17In Norwalk, art and music were a regular part of the curriculum taught by artists rather than art teachers.18From Catherine Gregory, the students studied music. From Frederika Moore, they learned modern dance.19Gwendolyn Cowan taught painting.20Over the years, Asawa has publicly repeated the names of these artist-teachers to underscore their influence and impact on her as working artists. Their passion and commitment to their own creative work rather than solely to their duties as teachers made a lasting impression. The music teacher Miss Gregory sang arias with such power that the blood vessels in her forehead looked as though they would burst. Asawa and the other children found this both amusing and inspirational and tried to achieve such an effect in their own singing—to no avail.21These regular artist-teachers were supplemented by visiting performers who graced the stage at assemblies in the school’s new auditorium, rebuilt after the old edifice “crumbled” during the 1933 earthquake (another example of the public investment in the educational infrastructure).22

Although the Yellow Peril fear of Asian immigrants translated into restrictive laws limiting the rights of Japanese Americans, in school Asawa recalls another stereotype, an iteration of the “model minority” myth. “They associated ‘artistic’ with the Japanese,” Asawa recounted in a 2003 interview. “So we were expected to be good students and interested in the arts.”23The dual edge of a cultural stereotype—the artistically inclined Oriental—pervaded Asawa’s life early on. Just as she negotiated the question of loyalty, Asawa seems to have accepted that her Japanese ethnicity may have subjected her family’s farming to exploitation by unscrupulous shippers,24while in the realm of art it may have had a positive impact. As later discussions of her work demonstrate, the association with artistic traditions of Japan provided a point of entry for interpreting the nature of her work.25

World War

On 8 December 1941, the principal of Excelsior Union High School spoke before an assembly of the student body and urged calm in the face of the war. A short time later, in an act that was repeated in Japanese American neighborhoods throughout the West Coast, Umakichi “dug a big hole to bury the Kendo gear, and burned the hakama, beautiful Japanese books on flower arrangement and tea ceremony, Japanese dolls, and Japanese badminton paddles,”26as Ruth’s older sister Lois cried out, “Oh, please don’t, don’t burn the books.” After all, she had brought these volumes back from Japan only months before.27In early February, two F.B.I. agents arrived at the Asawa farm to arrest Umakichi. While he ate lunch and a slice of lemon meringue pie baked that morning by his daughter Chiyo, the agents took advantage of the time to ransack the modest house, looking for suspicious material. Ruth ironed her father’s shirt while her mother packed a suitcase. Umakichi changed into his only suit and was taken away,28presumably because of his leadership in the local Japanese American community and his practice of Kendo.

With Umakichi’s cousin Gunji also picked up by the F.B.I., the extended Asawa clan was left without elder men at the helm. Umakichi was transferred among a number of holding cells and Justice Department prisons. An official hearing in May 1942 ordered him interned, first in Santa Fe where he was admitted in early July and later to the enemy alien detention camp at Lordsburg, New Mexico.29In recollections of the period, Asawa betrays little anxiety or fear about the circumstances of the war, despite the fact that the family was split. She and her family knew little of Umakichi’s whereabouts or the conditions of his imprisonment, and the youngest member of the family, sister Kimiko, remained trapped in Japan for the duration of the war.

In April 1942 the remaining Asawas packed their one-suitcase allotment, abandoned their pets, four workhorses, chickens, and farm equipment—and for Ruth, her prized collection of Campbell soup can labels.30The family drove their own car twenty-four miles to Santa Anita Racetrack, which had been transformed into a temporary detention center that ultimately housed more than 19,000 Japanese Americans before they were transferred to permanent camps.31The world of Santa Anita, though one of confinement, brought the dynamic world of Japanese America into one restricted location. The contrasts were startling. On the one hand, Asawa and her family were assigned to live in horse stalls only recently emptied of their former occupants. Horsehairs remained between the cracks of the boards, and the heat of an early summer accentuated the lingering stench.32But because the incarceration affected all Japanese Americans living on the West Coast regardless of education or class, Santa Anita—as the largest of the assembly centers, with Japanese Americans from Los Angeles, San Diego, San Francisco, and Santa Clara counties—effectively became a dense city of rich human resources. Almost immediately, the Japanese American inmates established a complex infrastructure in Santa Anita. A utopian spirit of self-reliance and proactive organization pervaded the camp. There were informal schools, published newsletters, baseball games, and talent shows, among other activities. As Asawa told one interviewer, “We really had a good time, actually. I enjoyed it.”33

Ruth’s internment identification card.

Although Umakichi never discussed his experiences with his children, the conditions in the Justice Department camps were vastly different from those of Santa Anita and underscore how the internment affected sectors of the population differently. A fellow inmate at Lordsburg, Rev. Yoshiaki Fukuda, recounted, “We were made to work on the construction of roads and airfield. We were also made to clean army stables, mess halls, and dancehalls. We were even made to transport ammunition … Furthermore, when our spokesman requested that we be allowed to rest during the extreme heat of the afternoon, the officer in charge threatened us by firing his pistol. The watchtower guards often threatened us by shouting ‘Japs, we’ll kill you.’”34Such threats did come to fruition. Nine days after Umakichi entered Lordsburg, two ill internees unable to walk the distance from the train station to the camp were killed by a watchtower guard. The deaths became known to the internees when some were forced to dig the graves. According to rumors in the camp, the responsible guard was praised for his “gallant action” and awarded $400 in donations at a local cafe.35The two slain Japanese men were fifty-eight years old: Toshiro Kobata was a tubercular farmer from Brawley, and Hirota Isomura, a fisherman with a bad back from San Pedro. For Umakichi and others, the resemblance to their own humble profiles must have been chilling.36While it seems evident that Umakichi’s personal loyalties remained with Japan, there is no evidence that he acted in any way to undermine the security of his adopted home.

Santa Anita existed in a parallel world. While her father was subjected to future uncertainty and the real possibility of death, Asawa was provided access to a dynamic community of artists, all of whom were Japanese American, an experience that would not have occurred without the incarceration. Thus, in a pattern that would repeat in other instances during World War II, the negative consequences of her Japanese ancestry turned into an unprecedented opportunity. A section of the racetrack grandstand, adjacent to a section where internees were used to weave camouflage nets for the war effort, became a de facto art studio. Painter Benji Okubo had been the director of the Arts Students League of Los Angeles, a position once occupied by his teacher Stanton Macdonald-Wright. In Santa Anita, he and painter Hideo Date, a League associate whom he had first met at Otis Art Institute, carried on the activities of the Arts Students League in the grandstand. They were joined by Tom Okamoto and Chris Ishii, who had attended Chouinard Art Institute. It was an informal arrangement borne of a confluence of boredom and optimism, yet it provided young, aspiring artists like Asawa with a chance to interact with artists whom they would have never met if the incarceration had not forced them together.

The varying experiences of these men provided models of an artist’s life. Date and Okubo were self-described bohemians who bucked conventions of the Japanese American community to live and work among artists who were primarily not of Japanese ancestry.37Before incarceration, Date had been employed by the Federal Arts Project, a precursor of the Works Project Administration, and, with Okubo, had exhibited extensively throughout California. Okamoto, Ishii, and Ben Tanaka were among the Nisei generation of Japanese American artists who found employment with Disney Studios. A principal expression of Asawa’s artistry as a young girl was to copy cartoons. Now she studied painting and drawing with Okamoto, one of the animators associated with the most influential force in this popular form. “How lucky could a sixteen-year-old be,” Asawa recollected.38The generative effect of this training had impact beyond Asawa. Among the group of students, she was not the only one to pursue a postwar practice as an artist. One of her “classmates,” Shinkichi George Tajiri, became an influential artist and teacher in Berlin and Amsterdam.39

Ruth (second from left) and her teacher, Mrs. Beasley (standing), with other students at Rohwer, 1943. Photograph by Mabel Rose Jamison.

When Santa Anita was closed and the Asawa family was sent to Rohwer, located in the wooded swamplands of southeastern Arkansas, it took only months before the camp was transformed by the ingenuity and labor of the inmates. As in life on the farm in Norwalk, every tangible material had to be utilized. Scrap wood became furniture, butsudans (Buddhist altars), or partitions for the undivided barracks. The seeds Asawa’s mother had brought from Norwalk were turned into a kitchen garden with elaborate trellises made of found wood and used string. Swamp trees cleared for roads and barracks were refashioned into children’s toys, such as a hobbyhorse, or hollowed out to form vases for ikebana, with foliage and flowers fashioned from newspaper, crepe paper, cloth, and any scrap material or plant material that could be adapted to that purpose. Hunting for kobu, the unusual growths found in hardwoods and especially prevalent in the cypress trees of the Rohwer swamps, became a popular pastime. The natural forms of the wood, sanded and hand polished to a glorious sheen, were transformed into objects of utility like doorstops or simply used to adorn the forlorn barracks. The kobu‘s metamorphosis from excrescence to beauty is perhaps the most powerful symbol of the daily transformations in the camps.

Unlike Santa Anita, Rohwer had officially organized schools for the children. Once again, Asawa had access to committed teachers who saw education as a means of democratization and considered art practice a central aspect of education. The high school English instructor Louise Beasley and art teacher Mabel Rose Jamison were two influential figures for Asawa.40As wartime labor needs diminished the supply of teachers, the War Relocation Authority was faced with difficulties in recruitment, exacerbated further by the stigma of teaching “Japs.” Perhaps such reactions emboldened the young teachers, who approached their positions with commitment and ingenuity. A description of Jamison and her search for art material could easily be that of Asawa’s forays with the Alvarado School some twenty-five years later. In a letter to Asawa, Jamison recalls, “The first year we HAD NO art paper of any kind except a few tablets and the notebooks some of you had brought with you. So—from the warehouse at Rohwer I begged some bolts of cloth—army uniform twill, and dark blue denim which we painted on, using Crayolas for the first sketches.”41The class projects were likewise borne of ingenuity. Jamison writes, “Do you remember all of our ‘hammered metal’ on tin cans from the mess hall with a few old nails? And our paintings on little rocks—the ONLY thing we had PLENTY of!”42The gift of a barrel of buttons prompted a project of jewelry-making, poster paint on fabric became mural-sized paintings, and paper was bound to make small journals and notebooks.43

Painted rocks and hammered metal created by students of Mabel Rose Jamison at the Rohwer Camp in Arkansas, CA. 1943. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Mabel Rose Jamison (Jamie) Vogel, 88.25.23-24. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

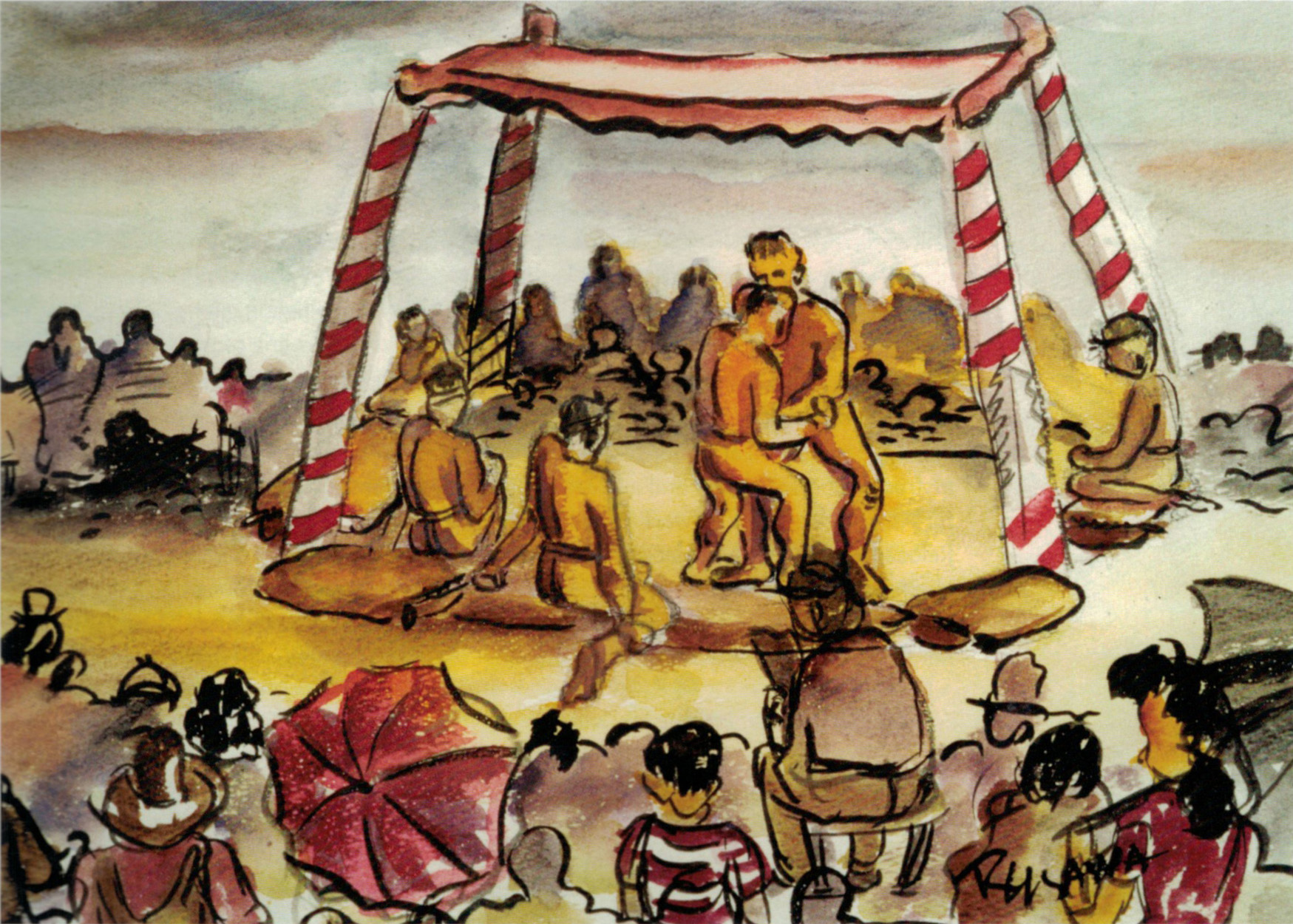

Little remains of Asawa’s artwork from this period. A watercolor of sumo wrestling conveys the frenetic activity of the sport and a crowd of kids and adults who seem to be enjoying the afternoon event. In the prewar period, sumo was especially popular in rural communities. Group entertainment like this occurred daily somewhere in the camp, whether it be a baseball game, talent show, or dance. While the watercolor is a lively depiction, nothing in it suggests the innovation and insight of Asawa’s artwork to come. Yet her identity as an artist was firmly formed . She was the art editor of the 1943 Delta Round-Up, a mimeographed annual produced by the high school. Asawa and a boy named Sam Ichiba were chosen by their peers as the “most artistic.” Jamison must have recognized Asawa’s early talent, as she followed her former student’s subsequent success with great interest.44The only two surviving watercolors by Asawa from the period were saved by Jamison, who returned them to Asawa decades later.

Asawa’s oldest sister, Lois, was the first to leave Rohwer, in June 1943, to attend William Penn College in Oskaloosa, Iowa. In August 1943 Asawa and her next oldest sister, Chiyo, departed: Chiyo to join Lois in Iowa and Ruth to attend Milwaukee State Teachers College, chosen by Ruth because it was the cheapest school in the catalogue to which she had access.45All three left under the sponsorship of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council (NJASRC), an initiative of the American Friends Service Committee that by the war’s end helped more than 3500 Japanese Americans attend college from the confines of the camps. The NJASRC worked closely with the camp authorities to secure leave clearances, recruit students from the camps, and identify colleges and communities that would accept Japanese Americans. More significantly for Asawa, once she was accepted, NJASRC raised funds to pay for tuition.46It is highly unlikely that Asawa, or many of the other Nisei, would have had the opportunity to attend college were it not for the financial and logistical support of the NJASRC. This was not the first time the Asawas interfaced with the Quakers, nor would it be the last. As children, the Asawas attended—despite the fact that the family was nominally Buddhist47—a Quaker meeting, where a Japanese pastor had been installed: “That was the only Christian church that accepted Japanese in [Norwalk], in our community. We could not enter a Presbyterian or a Catholic or a Methodist church at that time.”48The Quakers once provided a haven for Japanese Americans to worship. Now they enabled Asawa to leave. She was seventeen and had been incarcerated nearly sixteen months.

Ruth Asawa, Sumo Wrestlers, 1943. Watercolor on paper, 10¼ X 14½ in. Collection of the artist. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Away From Home

Milwaukee proved to be a hospitable environment for Asawa as she prepared for her vocation as a teacher. While she managed to find sympathetic homes where she worked in exchange for room and board and formed friendships with a dynamic group of artists, Asawa was told that no school in Wisconsin would hire a Japanese. Since her fourth year at college would consist of practice teaching, she was forced to leave the college without graduating. Once again, her ethnicity dictated the course of her future. As Asawa put it, “Had Milwaukee State Teachers College not rejected me and forced me to the alternative of Black Mountain College, I would have quietly retired as an art teacher with retirement benefits.”49

Asawa first learned of Black Mountain College before her prospects for teaching were dashed. For a couple of years, classmates from Milwaukee had spent the summers there. In 1945 her close friends Elaine Schmitt and Ray Johnson tried to convince her to join them, but Asawa chose to accompany her sister Lois to Mexico instead. Embodying a keen sense of adventure, Lois and Ruth traveled south to Mexico City by bus. The United States was still at war with Japan and her family was still in Rohwer.50At a bus stop in Missouri, “We didn’t know whether to use the white or colored bathroom,”51 but Lois decided they were colored, solving, for the moment, the question of Japanese Americans within American racial politics. In Mexico City, Asawa enrolled at La Escuela Nacional de Pintura y Escultura La Esmerelda, a newly formed art school, and the University of Mexico, where she studied with the innovative furniture designer Clara Porset. A Cuban immigrant who had trained in New York and Europe, Porset is considered a pioneer of Mexican industrial design. She had also spent time at Black Mountain College with Albers.52From another teacher, Asawa learned how to prepare a wall for fresco, assisting on a George Biddle mural.53

Black Mountain College

When Asawa arrived at Black Mountain College in the summer of 1946, she was only twenty. Yet despite her modest circumstances and young age, she had already traversed the United States—from Southern California to Arkansas to Wisconsin to Mexico and back again. She had studied and interacted with many significant artists and had lived on her own for nearly three years. The fact that no degrees were awarded attracted students who were interested in an alternative educational experience. For Asawa, the spirit of Black Mountain, the aging physical plant, and the school’s work requirements mirrored those of incarceration and her childhood farm. Thrift was required, collaboration was a necessity, and innovation that derived from modest transformations was valued over grand pronouncements. Student Albert Lanier, who would become Asawa’s husband, recalled, “It was such a poor school economically, but we had this gorgeous 640 acres. We had a farm. There were cows that gave milk. We had a cook. We ate our three meals together.”54The formalized Community Work Program required that students spend ten to twelve hours per week “on the farm, on the grounds, carpentry, electrical wiring, painting, etc.,” and official transcripts reflected compliance.55Among Asawa’s contributions were churning the butter and cutting people’s hair.

In Albers’s teaching, Asawa not only found a validation of her cultural heritage but also gained a language to describe the intrinsic philosophies embedded in her early experiences in Japanese school and Kendo. Albers gave the name Buddhism to the concepts that underlay the cultural practices of the Japanese American community. While some students could find Albers’s teaching methods difficult, with its emphasis on stripping down the artistic process to primary observation and the systematic exploration of basic concepts, such as figure-background studies, it also mirrored the repetitive actions of Japanese school training in calligraphy, a method that Asawa understood and experienced.56 57

Living room of the Asawa-Lanier home, CA. 1995. Photograph by Laurence Cuneo.

But it is Albers’s concept of matière that returns us to Asawa’s looped-wire sculpture. From Albers, Asawa believed that each material had its own inherent nature, which could be drawn out through combination, juxtaposition, or manipulation. “Each material has a nature of its own, and by combining it and by putting it next to another material, you change or give another personality to it without destroying either one. So that when you separate them again, they return back … to [their] familiar qualities.”58Her wire sculptures maintain this equilibrium. While they are essentially a line, through manipulation they become volumetric, yet they retain their essential “line-ness”: they could easily be unwound and returned to their initial state. Asawa goes further: “It’s the same thing that you don’t change a person’s personality, but when you combine them with other people, other personalities, they take on another quality. But the intent is not to change them, but to bring out another part of them.”59Inherent in an Asawa wire sculpture, then, are its various states. Not only does the exterior become the interior and back again, but the material contains simultaneously its past and future states. This becomes the ultimate metaphor for understanding Asawa’s Japanese American heritage. It is embedded in all of her work and at the same time also always fluid, moving from one state to another while remaining essentially itself.