Before leaving Los Angeles Siqueiros managed to paint one more mural, and the fact that it still exists today helps underscore the multiple ironies of context and ownership that play out across the decades of political mural art. This last piece was entitled

and was painted in a covered patio at the Pacific Palisades home of the film director Dudley Murphy.It depicts the Mexican “strongman” Plutarco Elías Calles, whom Siqueiros considered a traitor to the revolution (and who had effectively forced Siqueiros into exile), with bags of money and a gun. Opposite the menacingly unmasked criminal cower some women and a child, near the bodies of two murdered workers. It is a trenchant work, but made safely at a distance from its target—and behind the gates of a private residence.

The Bloc of Mural Painters—whose members included Luis Arenal, Reuben Kadish, Phillip Goldstein (later Philip Guston), Harold Lehman, and Sanford McCoy (an older brother of Jackson Pollock)—went on meeting after Siqueiros’s departure. Determined to keep their focus on contextually vital political content, they continued to experiment with cement as a potentially radical vehicle for their art and, responding to the problem presented by private property, developed a system for making portable murals. Together they made a series of these mural works for a planned exhibition at the John Reed Club on New Hampshire Avenue in Los Feliz. As Harold Lehman explains, their two themes were “the exploitation of labor by capital in America, and the other was the persecution of the Blacks.”The exhibition was to open in mid-February 1933, but on the evening of February 11, following a tip that a Communist organization was meeting, the Los Angeles Police Department’s “Red Squad” raided the club and destroyed three of the murals depicting elements of the Scottsboro Boys case.Various liberal arts groups protested this act of official vandalism by the Los Angeles Police Department, with one group, the Intelligent American Fellowship, based at West 106th Street, likening the raid to an act of the Ku Klux Klan. Captain William Hynes of the Red Squad rebutted these charges, saying at a press conference that the John Reed clubs were part of the international Communist Party and that the “so-called ‘Japanese Press Conference’ who were to hold a chop suey and social are, in reality, a group of Japanese Communists.”He did not offer any other rationale for the destruction of the artworks.

Discouraged, the artists of the Bloc soon dispersed, some to Mexico, others to New York, and the legacy of radical mural painting remained quiescent for several decades. Siqueiros’s

América Tropical lay forgotten under its layer of whitewash until the paint began to peel away, in the late sixties, and the historian Shifra Goldman photographed the devastated mural, which launched a long campaign to restore and preserve it.The rediscovery of Siqueiros’s presence in the city coincided with a new period of political activism and helped ignite an enthusiasm for mural painting across Southern California. This is typically understood as an expression of Chicano pride, but in fact many different ethnic groupings used outdoor murals to stake their place in the broader cultural history of the city. In addition, many nonpolitical artists saw murals as a way to expand their work beyond the confines of studio and gallery. Much of this work was done on the sides of small businesses and on freeway walls, water channels, and other spaces without the means or infrastructure to ensure longevity. Just as Siqueiros’s murals were made possible by technical innovations, most of these later murals were made possible by improvements in acrylic paint, which allowed artists to paint directly on many surfaces. But no paint is lightfast, and the California sun began to bleach the color out of these works quite quickly. Over the years various ownership changes, community changes, and a lack of interest and money have allowed many murals to fade away, get covered in gang tags or simply be whitewashed.

But sunlight and disinterest have not been the only enemies of outdoor murals; there have also been several instances of a more active suppression. In 1984 Barbara Carrasco, already well established as a banner maker and muralist for César Chávez and the United Farm Workers, was commissioned by the Los Angeles Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) to make a mural for the Olympic Games, which was to be held in the city for the first time since the summer of 1932, when Siqueiros was beginning work on

América Tropical. Planned to be a mural of similar dimensions, Carrasco’s

History of Los Angeles: A Mexican Perspective incorporated a number of vignettes from that history within the stylized strands of hair flowing behind a gigantic profile portrait of a young Chicana woman. In a prefiguring of Deitch’s recent decision, officers of the CRA found two of these vignettes—one depicting a mass lynching of Chinese workers and the other the internment of Japanese Americans—likely to offend, and decided against installing the mural.

Kent Twitchell, Ed Ruscha Monument (in progress), 1978. Courtesy of the artist.

Not every case of mural destruction has a political undercurrent, and two of the most significant in legal terms involve the oddly spiritual and deeply unconfrontational work of Kent Twitchell. In 1986 his well-loved mural The Old Lady of the Freeway was painted out by the owner of the building on Temple Street that supported it, in order to make way for a billboard. Citing the California Art Preservation Act of 1980, Twitchell took the landlord to court, and a monetary settlement was reached in 1992. In a strange repetition, another work by Twitchell, a giant, full-figure portrait of Ed Ruscha on the side of a government-owned building on Olympic and Hill in downtown, was whitewashed in 2006. This time Twitchell sued the US government and 11 other defendants, using the federal Visual Artists Rights Act as well as the California statute.Both laws prohibit the “desecration, alteration or destruction” of works of public art unless the artist is given ninety days notice to remove the work. Twitchell settled this case for a record $1.1 million in 2008.

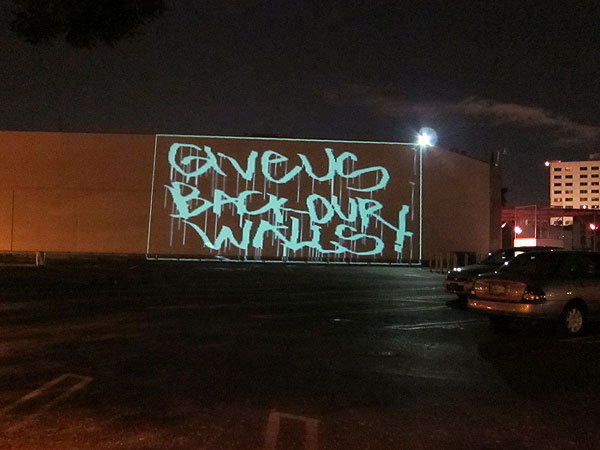

One evening in the wake of the recent whiteout at MOCA, a group of activists gathered at the parking lot on Temple facing the now empty wall. Using a laptop and a portable laser projector they presented a short program of protest, culminating in an image of Blu’s lost work with the word censored across its face as if stamped.There will always be a place for decorative wall painting, and artists will continue to find relevant uses for the mural genre, but the limits of the materials—the paints and walls—and the inevitable conflicts with property owners and their rights surely indicate that the mural has passed into history as a vehicle for political expression. Better to follow Siqueiros in seeking modern-day postindustrial techniques, as these protesters did. The portability, brightness, and high definition of the image, plus the ability to introduce motion and interactivity, provide politicized street art with a whole new world of possibility. It will be interesting to see if these new technical developments spur a significant new outpouring of public art with political intent.