Into the Sun of Sadness

by Travis Diehl

Even trees understand me! Good heavens, I lie under them, too, don’t I? I’m just like a pile of leaves.

– Frank O’Hara, “Meditations in an Emergency”

* * *

The Atlantic

Bas Jan Ader was living in Los Angeles when he conceived his final work of art. He would cross the Atlantic alone in Ocean Wave, a sailboat shy of thirteen feet stern to bow. The ship would be small, the sea would overwhelm. He would make a masterpiece whether he survived the trip or not.

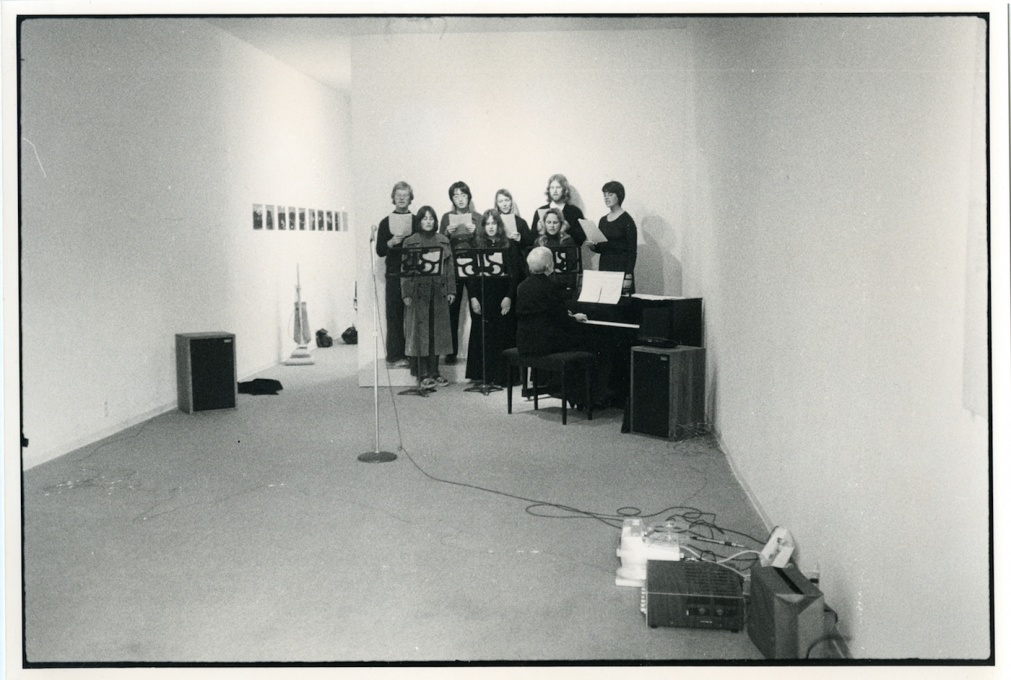

It seems clear, though, that he meant to make it. The journey (part two of a trilogy titled In Search of the Miraculous) was announced with a show at Claire Copley Gallery in New York; his students sang sea shanties at the opening, and a similar fanfare was planned in Groningen, The Netherlands, on the other side. And Ader was a seasoned sailor. He had arrived in Southern California in 1963 as a deckhand, aged 19, on a yacht from Morocco (which, ironically, shipwrecked). A decade later, he bought a boat in Marina del Rey, improved the rigging, and added a weathervane to the tiller so it would stay on course while he slept.

Bas Jan Ader, center spread for Bulletin 89, published by Art & Project, Amsterdam, 1975. © Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen / The Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

Bas Jan Ader’s exhibition opening at the Claire Copley Gallery, Los Angeles, 1975. © Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen / The Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

But Ader was also depressed. The film Here is Always Somewhere Else, a documentary by his countryman Rene Daalder about the artist’s work and disappearance, describes his financial and marital struggles in the years prior to In Search of the Miraculous. Daalder suggests that the heroic premise of Miraculous grandly satirized the conventions of American success. Ader set sail from Cape Cod on July 9, 1975. The following April, Spanish fishermen found the capsized Ocean Wave 200 nautical miles from the tip of Land’s End. Failing to reach B from A, Bas Jan submitted instead to more sublime standards, landing in the ambivalent space of incompletion, myth, and art.

Greta Thunberg, a Swedish teenager, was depressed too — about the reality of her generation’s future. “We saw a film in school,” she says in the documentary I Am Greta. “There were starving polar bears, floods, hurricanes, and droughts. … That’s when I started getting depressed.”1 She was nine years old. To assuage their daughter, her parents changed their lifestyle — driving an electric car, eating vegan — and encouraged her interest in climate activism. 2Greta grew intensely focused on her cause. In 2018, she began sitting outside the parliament building with a hand painted sign: skolstrejk för klimatet. Her “school strike for climate” sparked a movement. She pulled out of her funk. One year later, in August 2019, Greta boarded the high-tech, emissions-free yacht Malizia II at Plymouth, England and sailed for New York, where she’d been invited to address the United Nations. The Malizia rode the tide into port near Ellis Island greeted by camera crews, young activists, and a small fleet of sailboats bearing green slogans on their canvas.

These two dramatic, even desperate, Atlantic crossings are mirror images. Bas Jan was motivated by art, Greta by activism; he by mystery, she by science. Bas Jan faced the waves alone, a one-way radio to keep him company, while Greta and her crew — two sailors, a filmmaker, and her father — wielded a 21st century infrastructure of influence.3Both charted courses into the sublime: Bas Jan knowingly performing the Romantic tradition of man alone in nature, and Greta attempting, through the performance of her latter-day ocean crossing, to galvanize mass action against the sublime catastrophe facing our planet. But why the public expect such different results from the artist and the activist is just as telling. What does it mean for each when a loss goes unwitnessed? When a tragedy exceeds all our means to represent it?

The North Atlantic water plied by Greta Thunberg in 2019 was around one degree Fahrenheit warmer and 30% more acidic than that which claimed Bas Jan Ader’s life in 1975. The Arctic sea ice has reached record lows, and soon the combination of cold melts and sun-warmed open ocean will negate the currents that carried Bas Jan’s boat to the tip of Ireland. Greta made it. Bas Jan didn’t. It had to be so.

* * *

Ambition and dissolution run throughout Ader’s work. Miraculous in particular picks up the romantic tradition of art as an encounter with a natural world unbound enough to thrill and terrify at once, even to blot out the self (although not always the body).4This sort of fantasy became increasingly popular as industrialization engulfed the Western world in the late 1700s. A century after Young Werther produced his pistol, Marx described the “metabolic rift” that would bloom from the large-scale extraction of coal and metal ores into today’s total adulteration of the planet’s cycles, extremities, biomes, and capacity for life. A century later still, Bas Jan’s lonely search for the miraculous ironized art’s underlying intercourse between man and environment more or less taken for granted since Caspar David Friedrich perched his Wanderer on the rocks.5

Today, Miraculous gives precedent for a particular kind of tragic romantic affect that persists in (often northern European) artists like Ragnar Kjartannson and Olafur Eliasson, who deploy concepts like time, light, earth, even love as a metaphysical, four-dimensional sublime. These themes also recur, in a more self-reflexive, Ader-esque way, in the work of British artist Tacita Dean. To Ader’s intimation that even conceptualism has an underlying romance, Dean finds poetry in the quixotic quest — such as her interest in German writer W.E. Sebald’s searching novels, or an audio work from 1998 in which she attempts to locate Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (it was underwater). Her Disappearance at Sea I–VI (1995) comprises six large, turbulent seascapes drawn with chalk on chalkboards, less like the sea itself than the sea’s abstraction in the fickle modern mind.

Beyond the route and the map, searching, circling, losing, spiraling — in the words of Jack Halberstam, “out of the confines of conventional knowledge and into the unregulated territories of failure, loss, and unbecoming” — one finds erasure, mania, and death, but also rare genres of affect.6When Bas Jan missed his appointment in Falmouth, friends opened his locker at UC Irvine and found a book about Donald Crowhurst, a sailor who drowned himself during a round-the-world race. Crowhurst departed England in October 1968 but quickly abandoned course, resorting to faking his position reports to seem like he was keeping pace. The ruse worked too well: when two other sailors dropped out, he appeared to take the lead. Crowhurst received offers from publishers over the radio to print his fraudulent story. It would have been a good yarn. Instead, his Tiegnmouth Electron was found empty and adrift nine days after Crowhurst’s final log entry on July 1, 1969. The boat was purchased as a pleasure vessel and ended up rotting on a Caribbean island where, in 1998, Dean filmed and photographed its picaresque wreck in a series of eponymous works.

Tacita Dean, Aerial View of Teignmouth Electron, Cayman Brac 16th of September 1998, 2000. © Tacita Dean, courtesy of Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris.

Had Bas Jan made it to Falmouth, he would have beat the record for smallest craft used in an eastward transatlantic solo crossing by 2 feet 2 inches — but that wouldn’t have stood for long. (The current record, set in 1993, is under six feet.) Instead, he is remembered for disappearing. “But for Bas Jan Ader,” writes Dean, “to fall was to make a work of art. Whatever we believe or whatever we imagine, on a deep deep level, not to have fallen would have meant failure.”7Dean’s essay is titled “And he fell into the sea,” and begins with an epigraph about Icarus, yet another tale of the seduction and glory of failure: had his wings held, had he touched the sun, we would remember Icarus not as the fool who drowned but as the fool who burned alive.

This is the sublime extinction that Greta et al refuse, yet that all too many refuse to face. By the 1970s, nature’s innate sublimity had been somewhat subdued by deforestation, mountaintop removal, and deep-sea oil drilling. The acid ocean, wreathed in bleached coral, no longer simply represents the sublime scale of nature, but the sublime tragedy of nature’s collapse. “Global warming” entered the lexicon in the 1950s, “greenhouse gases” in 1975, the year Ader died. In a way, the simple but unfathomable fact that humans have profoundly damaged the survivability of our own planet has taken on the adventurous and tragic tenor of the Romantics, the way Miraculous exists in the moment when the artist surrenders to the possibilities of suicide.

In fact, it would be in character for artists to find a similar inspiration in the climate’s new chaos of droughts, hurricanes, heatwaves, and fires — the move from Earth to what Bill McKibben calls “Eaarth.”8Art’s pathos of loss contemplates the failure of activism (and activist art) to save the planet — a global suicide Goethe, Friedrich, or even Marx would not have imagined possible. Meanwhile, Greta’s critics accuse her of “hubris” for thinking human beings could possibly damage nature. A TIME magazine cover naming Greta person of the year in 2019 depicts her standing on a rocky shore battered by ocean spray, as if to invoke the romanticism of her quest to save the world.

The Mediterranean

Art is many things, but it is not urgent. Life would go on without it, however impoverished. Thus, the undertow of the rich world’s stubborn romanticism — our unilateral, recreational journey into and across the churning sublime — is guilt. Artworlders even have our own version of Greta’s flight-shaming. It’s a serious question (as Kyle Chayka writes, calling her crossing “a durational performance of two weeks”) whether the globalized art world can continue without the transoceanic jets that link our scenes even as they warm the air to death.9While thousands of climate refugees crowd into unworthy boats and rafts, collectors ply the Mediterranean in their yachts, like the one decorated in razzle dazzle pop art camo by Jeff Koons for Cypriot industrialist Dakis Joannou. The ship’s name, painted across its transom, is Guilty.

It may have been this ostentatious display of privilege, afloat on blood-dark seas, that British “street artist” Banksy had in mind when he posted on Instagram that, “like most people who make it in the art world, I bought a yacht to cruise the Med.”10The Louise Michel is not a pleasure ship, but a lifeboat run by an NGO with a mission to rescue refugees stranded between Africa and Europe. The ship set off in secret from Spain on August 18, 2020, emblazoned with a magenta spray paint design and a Banksy stencil of a girl holding a heart-shaped life preserver. Banksy bought the ship with the proceeds from refugee-themed artworks; obviously, he wrote in an email to Pia Klemp, the ship’s future captain, “I can’t keep the money.” Nor does he manage the boat’s operations. “Banksy won’t pretend that he knows better than us how to run a ship,” Klemp told the Guardian, “and we won’t pretend to be artists.”11

While some artists maintain a bright line between art and activism, others work in the blur. One of the first projects by Forensic Architecture described the harrowing ordeal of the “left-to-die boat” in March and April of 2011, where all but nine of a group of 72 migrants lost their lives while NATO ships watched. FA’s video charts the rubber boat’s departure, where its motor died, and how it drifted for days before the survivors finally washed back up in Libya.12The project is a visualization of the facts and has been presented as evidence in legal complaints as well as in art contexts.13The work’s forensics counter the programmatic ignorance of European authorities who won’t answer mayday calls, and populations who refuse to see the humanity of the emergency — rafts with no names, full of people whose names we’ll never know.

FA has returned to the refugee crisis in projects from 2015, 2018, and 2020. Trained in architecture and design, the group is able to make horrific events “presentable,” a combination of videos, diagrams, simulations, primary documents, and reconstructed maps — dark teal with dingy yellow and cyan overlays representing “zones” of action or inaction, etched with paths. Elsewhere they do the same for state murders, drone strikes, even the Grenfell Tower disaster. This well-designed activism is readily embraced as art by the art world, perhaps in part against its guilt for being other than activist, less than political enough. In this cultural context, too, FA’s work emphasizes problems of visibility and voice to an audience primed to think in these terms.

It is placed, like Turner’s painting of the drowning slaves of the Zong, counter the romance of the sea and its first world abstraction into the sublime. Further, FA’s deployment of the evidence troubles the tendency of white “Western” art to glorify loss, disappearance, and the interplay of visibility and in- that characterize Bas Jan Ader and Olafur Eliasson’s emo conceptualism. The mystifications of art can only hurt the victims of globalism’s abstraction, for whom the sea is mostly horror.

Launch of the Ocean Wave, Chatham Harbor, July 1975, photo by Mary Sue Ader Andersen. © Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen / The Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles.

The Sparkling Sea

“We’re often told that art can’t really change anything,” writes British author Olivia Laing in the introduction to her collected writings, Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency, published in May 2020. “But I think it can.” And how? “It shapes our ethical landscapes; it opens us to the interior lives of others. It is a training ground for possibility. It makes plain inequalities, and it offers other ways of living. Don’t you want it, to be impregnate with all that light? And what will happen if you are?”14

In May 2011, a month after the left-to-die boat tragedy, Laing published an article in which she describes her peripatetic path to culture writing. Laing dropped out of college at age twenty to join “a tiny protest camp in Dorset” where activists protected “a strip of much-loved woodland” by living in the trees. “There was a net slung in the canopy,” she writes, “built as a defence for when the bailiffs came. Lying up there among the leaves, you could see the glittering blue ribbon of the sea a mile south.”15The so-called Teddy Bear Woods were saved. But, “like many ex-protestors,” writes Laing, “I’d begun to buckle under the strain of trying to avert – trying even to articulate – an oncoming catastrophe.”16Laing spent a summer living alone in a field in Sussex, then became a journalist.

Laing would continue to probe the connections between art and politics in her writing for magazines like Frieze, not least the column she began in 2015 called “Funny Weather.” The title itself declares a latent romanticism, if not environmentalism. “I chose ‘Funny Weather’ as the title,” she writes in “You Look at the Sun,” the book’s introduction, “because I was imagining weather reports sent from the road, my primary address at the time, and because I had a feeling that the political weather, already erratic, was only going to get weirder.”17Throughout the collection, Laing uses weather as a metaphor for politics — painting current events as something perhaps influenced, heightened, or extremized by human behavior, yet ultimately capricious, out of control; to be endured, not changed.

Here, Laing echoes Ader’s impulse to surrender to nature, merge with it, and disappear. “When I was a very small child,” she writes, “I was obsessed with a picture book called The Green Man, in which a rich young man who goes swimming in a forest pool has his clothes stolen from him and is forced to live in the wild.” Ever since, “I’ve periodically wanted to vanish into nature too,” Laing admits, “and at the age of twenty I almost managed it.”18The Green Man fell from the civilized Europe into the pagan one. But for privileged inhabitants of the rich world like Laing — or Ader or Thunberg — such a disappearing act is usually voluntary.19Despite his former wealth, the Green Man is ultimately more like the refugees adrift in the Mediterranean, swallowed by the metabolic rift.20

Indeed, Thunberg’s thankless mission is to convince the rich world that our forays into the sublime are no longer elective matters of the self. They are existential, communal, and total. The house, as Greta says, is on fire. In a column on the Grenfell Tower tragedy, Laing writes of Turner painting a burning building, “Set it down: as spectacle and artefact, as testimony, witness report and permanent record. The sky is rose-pink, rose-yellow patched with blue; the sky is very lovely, full of small gold darts of burning debris. Here’s the first challenge: how not to aestheticize tragedy.”21But Turner’s building was empty. The sea he depicted around the Zong was not, and neither is the burning Earth. Don’t romanticize doom; don’t treat an ashen sky like a Rothko. But don’t look away, either.22

The cover of Laing’s book features a work by David Wojnarowicz: “a photograph in the desert of his own face, eyes closed, teeth bared, almost buried beneath the dirt, an image of defiance in the face of extinction.” In her first Frieze column, from December 2015, she compares another work of his, a self-portrait with his lips sewn shut, to journalistic photos of migrants on hunger strike who sewed their mouths closed as a protest against the inhumane conditions of detention camps. Perhaps, as she writes, images can speak for the voiceless: “You make a migrant image, an image that can travel where you cannot.” Art certainly makes equivalences. “Both images are in front of me now,” writes Laing. “David [Wojnarowicz] is dead. God knows where the man on the Greek border is.”23Of Laing’s two images, one art and one not, the one shows us the other, the other shows us ourselves.

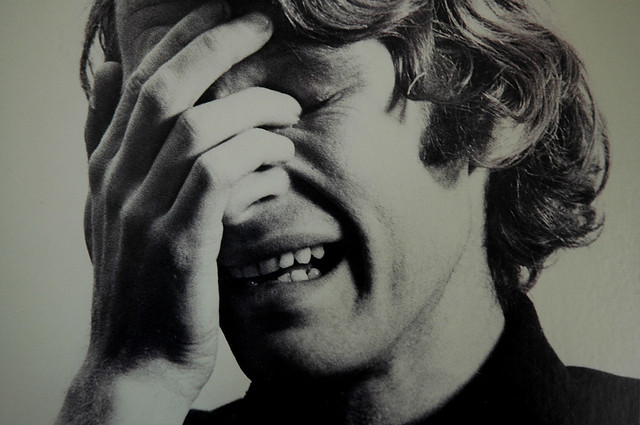

Bas Jan Ader, film still from I’m too sad to tell you, 1971. © The Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen / The Artist Right’s Society (ARS), New York, courtesy of Meliksetian | Briggs, Los Angeles and Simon Lee Gallery, London.

Greta Thunberg reacts during a session at the European Parliament on April 16, 2019. © Frederick Floring / AFP / Getty Images.

Two Tears

Two more images: Bas Jan Ader, his hand clawed to his face, his crows’ feet wrenched and his teeth bared in apparent pain. The frame is black and white, the background indistinct. And Greta Thunberg, both hands wiping tears from her eyes, an aluminum water bottle and a microphone to the left of the frame, and the EU flag in soft focus over her shoulder. Greta has broken down momentarily after addressing the EU parliament’s environmental committee, four months before she sailed west. Greta often gets “emotional” during her appearances — for which she is mocked, called a child by her critics when they’re not calling her autistic, not emotional enough. But who wouldn’t cry — describing the pace of the sixth mass extinction and the impotence of world leaders’ climate goals? Her sadness and her anger are immediate, urgent, intertwined; and their cause — our failure to save the planet — is explicit. Bas Jan’s image, though, comes from a suite of works from 1970/1971 — photographs, postcards, and a 16mm film — titled I’m too sad to tell you. In the film, the artist rubs his eyes, breathes heavily, works himself up. Whereas Greta is eloquent and incisive, Bas Jan forms a sadness that won’t form into words. His is a journey into the ineffable, an interior Miraculous, where the sublime idea of nature suggests human emotions too great to be expressed. Do we take Ader’s final performance as an ironic image of the passion of the white male artist? Or is it a genuine example? It is both.

“Our house is still on fire,” Thunberg told the WEF in Davos in 2020. “Your inaction is fueling the flames by the hour.” Ader chose a sort of suicide of meaning, as misty and cold and unfathomable as the sea that took his life. This ambivalence is crucial to art. Yet we would interrogate art to death, while muddying activism with hypotheticals. The critic Jennifer Doyle describes the incommensurate perception that male tears, because somehow repressed and unacceptable, read as a sincere upwelling of strong feeling, while female tears are taken as a performance.24The same can be said of the cross-purposes of art and activism. One refuses to be clear, the other demands it. Neither is wholly believed.