Lost Opportunities: The Early Work of Don Dudley

by Saul Ostrow

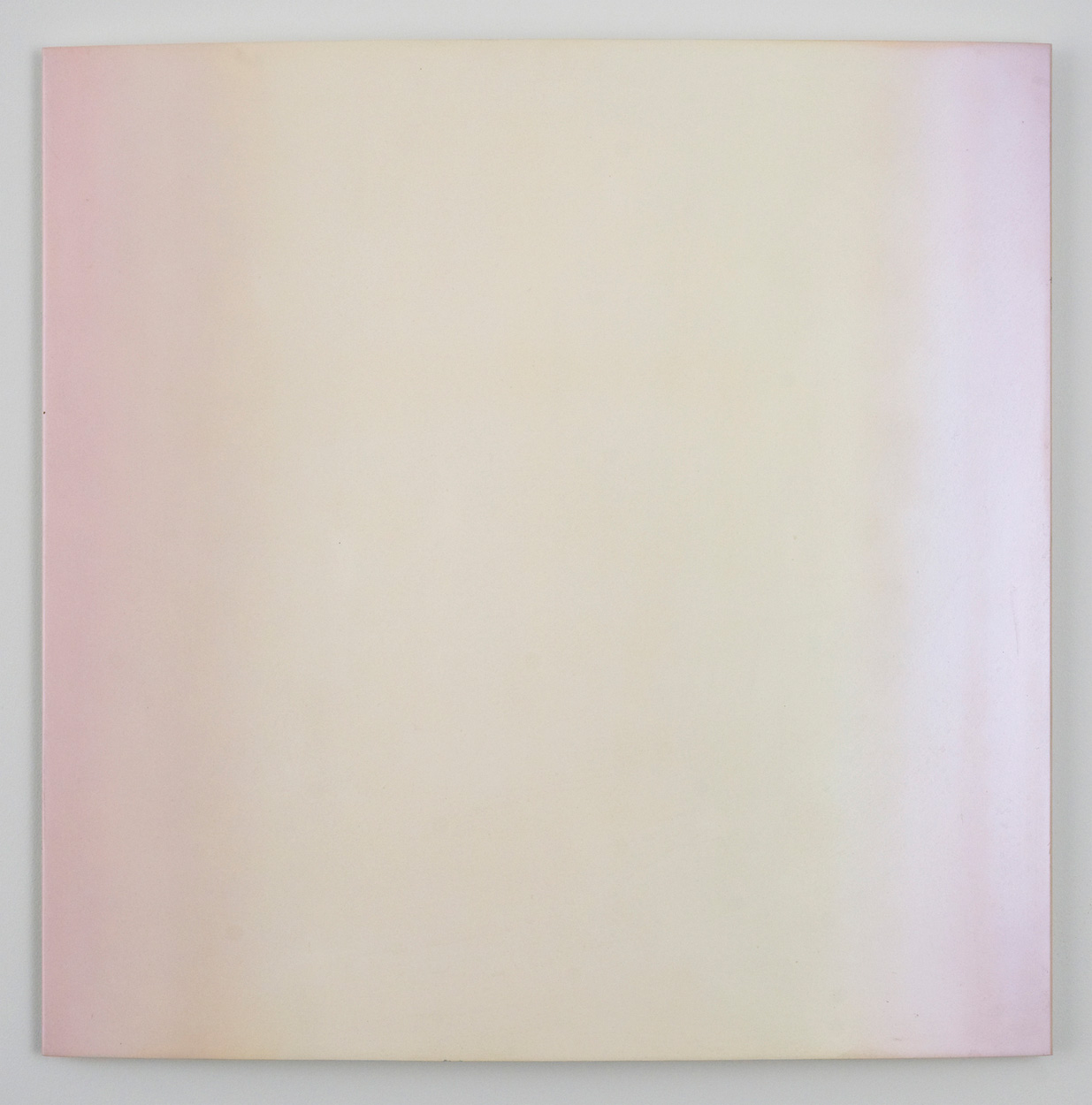

Don Dudley, Murano II, 1967. Acrylic lacquer on aluminum, 22.5 x 22.5 in. Photos: Cary Whittier. All images courtesy of the artist and I-20 Gallery, New York.

Last spring I went to a dinner in New York at the loft of the artist Don Dudley. In the seventies he made some great Minimalist works that literalized flatness as structure as well as surface, and he exhibited a modular piece at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1972. By the eighties he was exploring the space between painting, sculpture, and design by producing object-like works that embodied a sense of imminent functionality. A selection of Dudley’s work from 1966-79 is currently on view at I-20 gallery in New York, his first solo show in 25 years. I’m not sure how, but the conversation that night drifted around to the subject of Dudley’s having come east in 1968 from LA. This was perhaps a strange time for a young artist to leave, just at the moment when Southern California was emerging with an art world identity of its own.

There was a new sensibility developing, an attitude that was characterized as “cool,” and broadcast an in-your-face hedonism at odds with the darker stance affected in New York. On the East Coast, artists inhabited abandoned manufacturing spaces and tended to identify with the workers in the old iron and steel industries of the rust belt. In Los Angeles, by contrast, artists were more aligned with small, specialized contractors in the aerospace, automobile, and furniture-building industries. They were experimenting with new materials and finishes—plastics and resins, molded wood, aerosol paints—to make work that examined the phenomena of space and light, the forms of an car-dependent mass culture. These artists ranged from Larry Bell to Robert Irwin, Peter Alexander to Craig Kauffman, Billy Al Bengston to Ed Ruscha. Many of them showed with the resurgent Ferus Gallery, by this time no longer a beat collective but an ambitious commercial enterprise.1These diverse artists were united by the principles of color, materiality, precise craftsmanship, and intellectual rigor. In the midsixties Dudley was a young artist trying to break into this scene, finding it more closed than he would expect.

After spending a year and a half in Mexico, Dudley and his wife and children had returned to San Diego in 1959, where Dudley found a job working at the nearby La Jolla Art Museum. He exhibited his work around La Jolla, but in 1964 they decided to move back to LA (his birthplace). He continued to make artwork but couldn’t get anybody to take much interest in it, so he decided he needed a new start in a new city. He loaded up a station wagon with everything that would fit and put the balance of his work from 1958 to 1966 into storage. His intention was to give New York a year and then come back if things didn’t work out. Well, things did work out—as evidenced by the shows he quickly got. The problem was that he couldn’t afford to continue to store his work in Los Angeles or to have it shipped, so he had a friend document the pieces and then destroy them, following the example of his fellow San Diego–to–Los Angeles outsider, John Baldessari.2

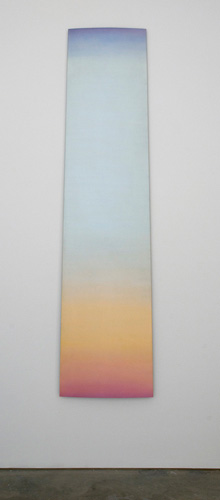

Don Dudley, Skysnare, 1966-67. Acrylic lacquer on aluminum, 84 x 21 in.

Knowing this story, my fellow dinner guests and I were all interested in finding out what kind of work the young Don Dudley had been making in his brief Los Angeles stint. So, Don went into the storage area in his apartment and pulled out a glassine-wrapped work from the period, one of the pieces he had fit into his station wagon all those years before. What emerged from the packing material appeared to be a monochrome spray painting on a rectilinear metal support, whose surface was slightly convex. It was pristine, and looked as if it could have been made yesterday. Most significantly, the piece did not carry a sense of déjà vu—it was not familiar at all. What Don had done in his own unique way was synthesize LA’s sixties aesthetic and intellectual concerns into a single plane of color. If Dudley’s painting had any affinities, it was to Robert Irwin’s dot paintings, and his disks from 1966–69, or David Novros’s fiberglass modular paintings, and the cast-resin sculptures of Peter Alexander.3

The story does not end here, though. Dudley was planning to hang some of these works in his loft on the occasion of his eightieth birthday party. After some further discussion I offered to host the party and exhibition at my house. The resulting installation included ten works, all of which are are on aluminum that is very slightly convex and is supported from behind by a thin wood structure.

The works are modest in size, ranging from squares (22 by 22 inches) to tall (84-inch) verticals whose rectilinear forms slightly taper from 22 inches at the bottom to 19 inches at the top. The vertical edges of all the works are very thin, so rather than protruding they hug the wall. In this manner Dudley counters the thickening of the stretcher bar that began with Jasper Johns and Frank Stella as a means of emphasizing painting’s objecthood, and which Tony Delap was using at that time to illusionistic ends.

Dudley’s works appear at first to be monochromes, but they really aren’t. The colors range from a decoratively appealing palette of whites, to saturated yellows and violet and blue metallic (metal flack-looking) pigments. Liminal shifts of color and tone produce noticeably different spatial and perceptual effects. In part this is because Dudley used industrial lacquers with a Murano antireflective coating, whose application in differing directions catches the light in a distinct manner. The destabilizing effect of the paint, the shape, and the convex surface emphasize the integral relationship between each painting’s physical size, materiality, composition, and form.

Don Dudley, Sky Prism, 1966-67. Acrylic lacquer on aluminum, 21 x 21 in.

The slightly bowed surface causes shifts in color, or appears to. In some cases, such as in Sky Prism, or the vertical Violet Prism, a spectral effect (or halation: a bright patch of light) has been painted into them. In Murano I, II, and III, the color shifts respectively take place at the edges or inversely down the center. These effects at first look as if they are a result of reflection or refraction due to the slight bowing of the work’s surface, rather than Dudley’s intentional intervention into the literal nature of the work. The one exception to this formula is Skysnare, a lyric, multicolor, almost Rothkoesque vertical work whose soft-edge transitions from orange, to yellow, to white to blue from bottom to top push the work in a direction where object, optical effect, and color transitions do not come together as an integrated transcendent whole.

Given Dudley’s pared-down vocabulary and ostensible anti-illusionism or literalist approach, we might think of him as a formalist. Yet his works articulate a very different type of formalism from the one being practiced on the East Coast at the time. These works’ particular qualities move beyond the reductive definition of painting as object and process that was being advanced by Brice Marden and Robert Ryman, and instead encourage a more phenomenological or analytical understanding of painting (both the act and the thing) as being a complex assemblage of material characteristics and optical effects. Yet they are more physical and material than works by Robert Irwin.

The exciting thing about this group of works, beyond their aesthetic effect, is that they are a reminder of the multifaceted issues concerning color, surface, and materiality that stem from Minimalism’s (and art concrete’s) concern with the ambiguous nature of painting’s objecthood. In turn, from these works one gets the sense of an important course within Minimalism as well as abstract painting that has gone unacknowledged and unexplored. This is not to imply that Dudley didn’t follow the right path, given that the specific objects, which all deal with oblique observation of the seventies, are equally rich—and if things were reversed I would probably be bemoaning the fact that Dudley had followed the course indicated by these paintings, rather than the one he did.