Luciano Perna (1958 – 2021)

by Thomas Lawson

In a 1993 interview in Bomb, Luciano Perna described himself as “an international folkloric artist,” and went on to refine the definition by underlining his “anxieties to be contemporary.” The international aspect is easy to parse; a born Neapolitan, he spent his teenage years in Caracas, before moving to Los Angeles in 1979 to study at CalArts. At CalArts he worked with John Baldessari and Douglas Huebler, with Judy Fiskin and Jo Ann Callis, but somehow managed to maintain an outsider stance, refusing to be limited by any kind of professional descriptor or national identity. He read the books, saw the shows, but always stood slightly athwart, calling BS. He always took photographs, but also sometimes painted, and often made constructed sculptures using found materials scavenged from flea markets and food stores, old Weber grills and cheap spaghetti. Through these materials he composed elaborate visual puns and creaking jokes about modern art and culture—imagine Mario Merz with a sense of humor.

In his obituary in the Los Angeles Times, Christopher Knight describes one of these odd objects, an edition of small flashlight sculptures that clearly referenced works by Jasper Johns and Claes Oldenburg. But instead of realistic (if out of scale) replicas made of bronze or steel, Perna used a variety of common objects, from plungers to clothespins, to make a jerry-rigged contraption that actually casts light—an absurdity that deflates the big-time art questions about representation, while also throwing light on the real world.

Perna’s photography had a similarly subversive cast, unobtrusive documents of an art world unfolding through the 80s and 90s. Well-known in Los Angeles, he obtained credentials and invites to art fairs and symposia, gallery openings and backrooms. Once there he took black and white photographs of the many habitues, rising and forgotten; an archive of hopes and dreams. In a 2020 essay in Artforum, Benjamin H.D. Buchloh describes this as a “photography of standardizing negligence,” recording not-quite haphazard encounters with a perplexing informality that captures the randomness of so much art world activity.

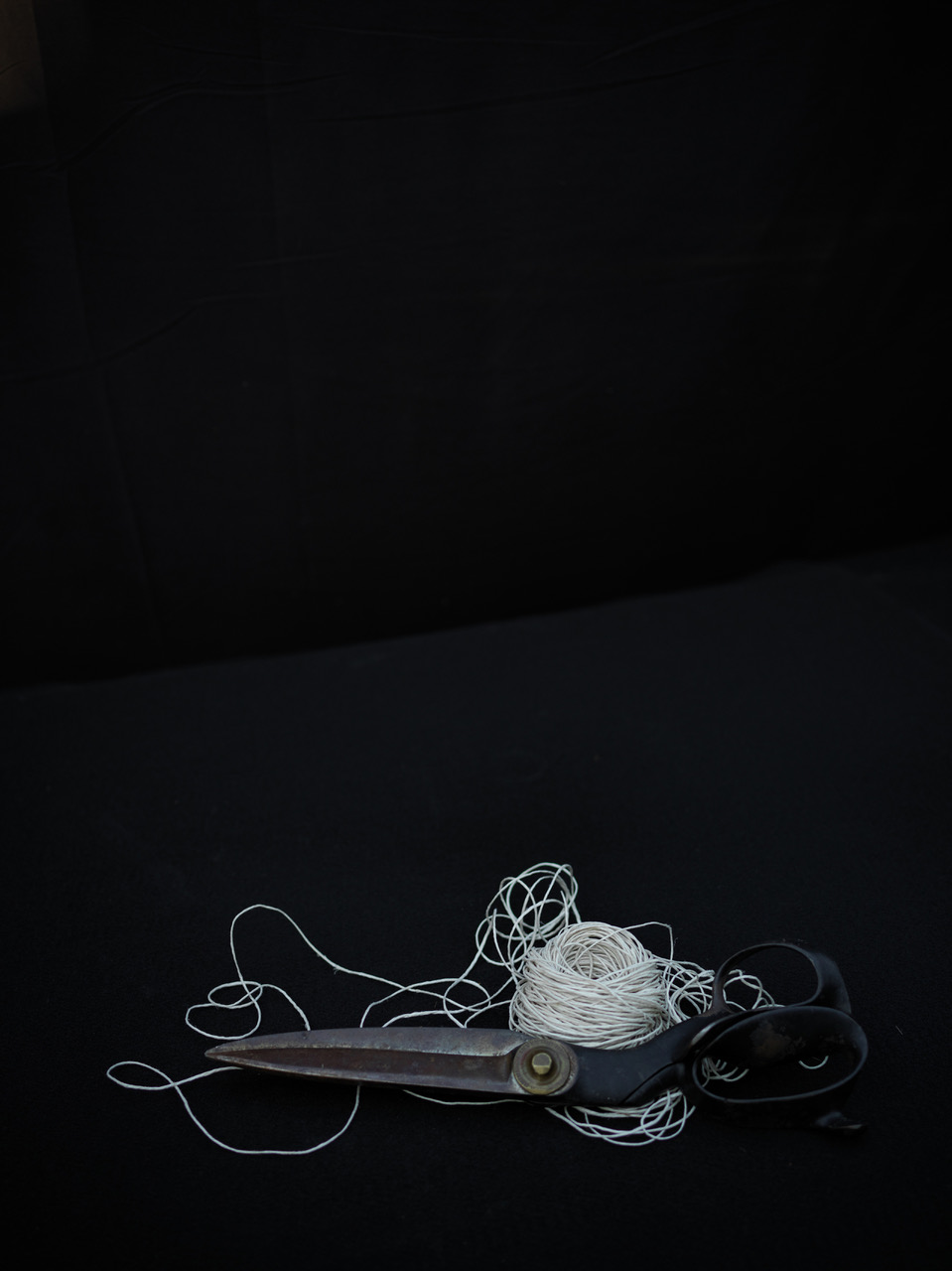

Buchloh’s article was precipitated by a chance encounter, on social media, with a more solemn body of work that Perna began in spring 2020, in response to the COVID-19 lockdowns. These were photographs of plants and shells, everyday tools, and cutout postcard reproductions of classical sculptures, all against an impenetrably black backdrop. As Buchloh notes, these images are firmly within the memento mori tradition of Dutch still life, an altogether more somber tradition than Perna tended to look toward. But scrolling through his Instagram account from that March and April, a distinct melancholy can be sensed encroaching on the pervasive sense of the ridiculous. There are still pictures of frying eggs and oddball studio setups. But there is also, on March 16, a screen shot of a newsflash announcing that Trump is calling for limits on gatherings of more than 10 people, and that the Bay Area is going into lockdown. An announcement for an upcoming show in Zurich is titled The Unknown, The Unanswered, The Unfinished, followed by a youthful self-portrait, in Naples 1973. Then, on April 22, the first of these dark still life images, a potted plant, blooms glistening in light against an opaque velvet black. The beginnings of a series that Buchloh describes as “blossoms of current confinement and despair” triggering grave, yet slightly satirical, contemplation of our material losses. Similarly, in String in Four Parts, a ball of twine extends across a quadriptych of black panels, only to be met in a final fifth image (Scissors and String, 2020) with a pair of heavy metal shears, inevitably conjuring the Fates, as Buchloh notes. The image lands as a deeply felt foreboding.

Luciano Perna was born in Naples, Italy on January 14, 1958, and died in Los Angeles on December 28, 2021. He is survived by Darcy Huebler, his wife of 35 years.