Michael Asher: There is Never Enough Time to Get Everything Said

by Thomas Lawson

The gallery of Otis Art Institute of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, California, USA, February 24–March 9, 1975, the announcement board in the lobby. Courtesy of the Frank J. Thomas Archives. Photograph by Frank J. Thomas. © Michael Asher Foundation.

“But for me, this has always been thought of as a shared experience. I do not have an ultimate notion of what art is; therefore, if I use the written word or something of that sort, it has a particular interest for me. And if the result is a presentation (if for nobody but me) but can be shared and has the potential, I am willing to attach the word “art” to it.”1

* * *

Michael Asher’s work was ever as slippery as thought, inviting a sudden understanding, a new way of looking at something, and then gone. Asher generally conceived a work for a particular space and time; he would add or subtract something, change something, in the hope of increasing his viewers’ perception of that environment’s context, and perhaps also deepening their understanding of the conventions and structures that make contemporary art visible and meaningful. He changed the configuration of gallery spaces by moving or building partition walls, thus drawing attention to the dimensions of rooms, the passage of light, the effects of sound. He even manipulated air flow, highlighting a less tangible, but equally present understanding of movement through space. And in some instances, in the 1970s, he threw light on the question of the presence of the artist himself in the frame, a question that in turn illuminates the importance of time in the reception, and understanding, of any work of art.

The work was intentionally temporary, and, in the early years, documented mostly in black and white photography and in a 1983 monograph that he published with the Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD). Writings 1973-1983 on Works 1969-1979 has long been out of print, with the practical effect that only one or two of the works, out of a total of 34 completed projects from the 60s, 70s, and 80s, have remained in any way visible. This now changes with the recent re-issue of the book from Primary Information, which has allowed for the following reconsideration.2

On reading through the book, it becomes clear that while Asher is best known for the projects he undertook in various museum and gallery contexts, he also worked within a number of generally less considered spaces within art schools. What this suggests is that he was not only interested in the phenomenology of viewing within the institution, in exposing the mundane work of the gallerist, and complicating the role of the viewer, but also in ways the artist teacher might lead students in a fundamental examination of how to think about art by considering the elements that allow a work to become seen. This body of work (1969-1979) was largely completed before he began teaching his renown Post Studio Art critique class at CalArts,3 and can perhaps be understood as preparation for it.

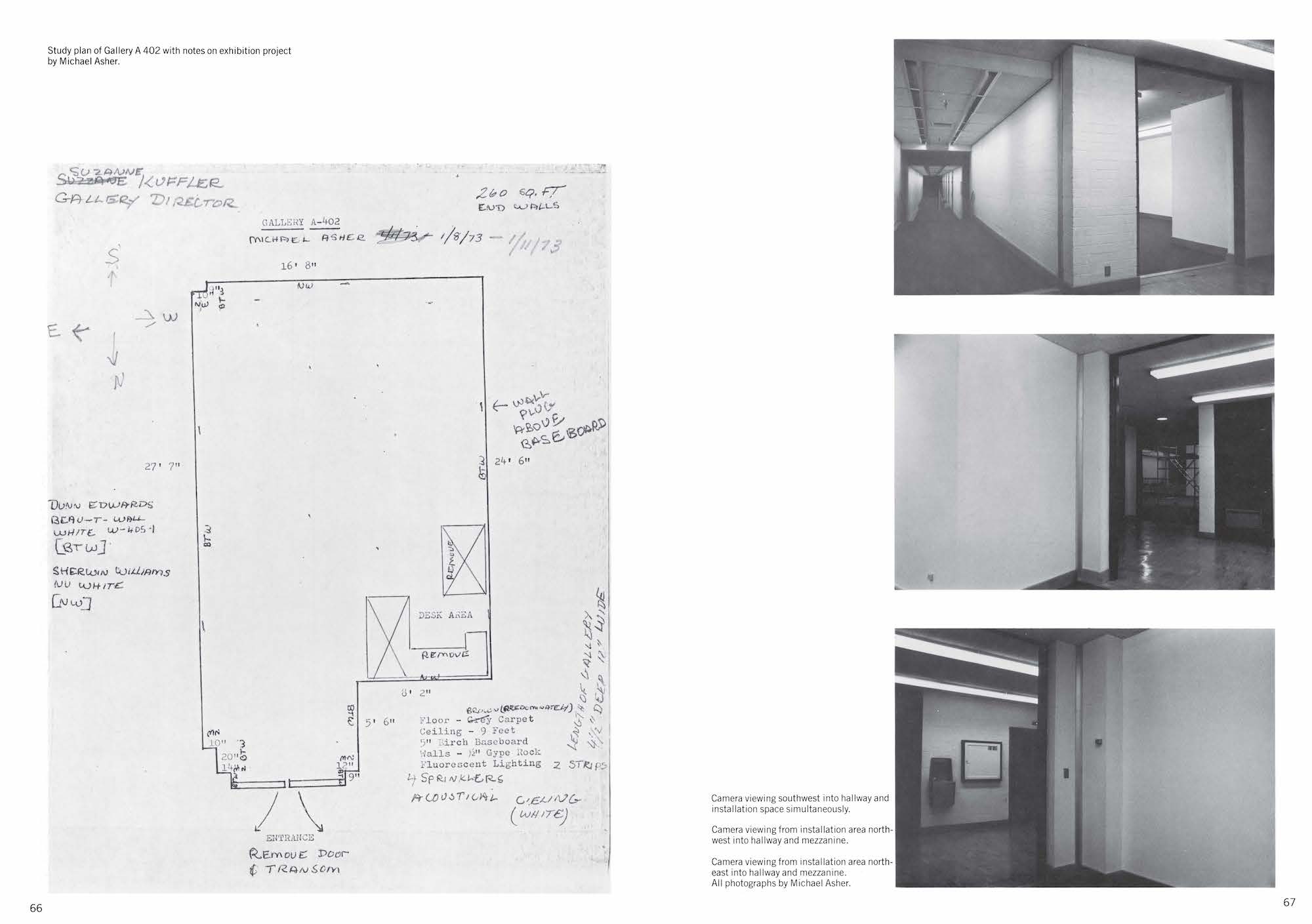

Pages 66 and 67 of Michael Asher, Writings 1973–1983 on Works 1969–1979, ed. Benjamin H. D. Buchloh (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design; Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1983; Primary Information, 2021). © Michael Asher Foundation.

Asher came to believe that the purpose of advanced study within the art school context was not about honing skills as much as it was about sharpening the students’ discursive abilities. He wanted to prepare them to be thoughtful about their work, and to understand what they were doing so that they might be prepared for a professional career.4 He rarely discussed his own education, but it does seem worth noting that he was an early graduate of the Studio Art Department at the University of California, Irvine (UCI), the first self-consciously progressive art school focused on contemporary practice established in Southern California,5 and where he would have witnessed a move away from traditional art making to thinking in more conceptual terms about perception. The first faculty at UCI included Tony DeLap and John McCracken, who used industrial painting techniques to create immaculate abstractions that challenged the relevance of representational art, and some of the first works that Asher exhibited fit this mold.6 These “Finish Fetish” artists were soon joined by Robert Irwin, who was moving away from making any kind of art object toward a more speculative investigation of the light and space that surrounded it. Asher was no longer a student at this point, but his close friend John Knight was, and the work both made in the following years shows a clear engagement with Irwin’s ideas.

During the late 60s, Irwin was working with several small manufacturers to create convex disks which he then installed to create a confounding perceptual problem in which light and shadow seemed to dissolve the object. White seemed to take on color, solids dematerialized, and shadows became solid.7 Asher would take this ethereal dematerialization and make of it what William Hackman has called “a more contentious anti-materialism,”8foregrounding the implicit tension between the intention of the artist and the work’s reception by a viewer.

Perhaps as important as Irwin’s experiments in perception was his famed accessibility as a teacher, his willingness to talk to anyone expressing interest for as long as it took. As a teacher he felt it was his responsibility to instill enough confidence in technical ability that anxiety over it couldn’t become a block to progress and, simultaneously, to make sure that students had a historical context of sufficient specificity to work within. Following that, he would insist that students took responsibility for developing their own ideas, instead of relying on any assignments he might give them.9

Gladys K. Montgomery Art Center, Pomona College, Claremont, California, USA, February 13–March 8, 1970, detail of entry/exit and view into constructed triangular area. Photo taken with daylight. Photograph by Frank J. Thomas, courtesy of the Frank J. Thomas Archive. © Michael Asher Foundation.

Gladys K. Montgomery Art Center, Pomona College, Claremont, California, USA, February 13–March 8, 1970, viewing out of gallery toward street from small triangular area. Photo taken with daylight. Photograph by Frank J. Thomas, courtesy of the Frank J. Thomas Archive. © Michael Asher Foundation.

Between 1969 and 1972, Asher, still in his late twenties, completed nine projects for a range of museums in California and New York, from the Newport Harbor Art Museum to the Museum of Modern Art. These installations all shared an interest in the physical structure of institutional space, the actual conditions in place to make art visible to the public. In many ways the most fully realized of these projects was also one of the earliest, a well-funded invitation from the gallery director, Hal Glicksman, to take up residence at Pomona College and develop an installation on campus, at the Gladys K. Montgomery Art Center. Famously, Asher had the street doors removed, meaning that the gallery was by default open to the public at all hours. He also reconfigured the gallery walls so that it was impossible to see into the main gallery area from the entryway. It was equally impossible to see out to the street from inside, although from inside visitors would be aware of natural light and fresh air. In a later interview, Asher spoke of his interest in the flow of this air: “I built the two triangular spaces like an architectural wind instrument, and in the large chamber you could often hear street sounds louder than in the street. The sounds would be amplified through the small triangular space.”10

This extraordinary streak culminated with an invitation to participate in Documenta V during the summer of 1972. Documenta V was organized by Harald Szeemann, the Swiss curator who had first brought international attention to the Post-Minimal generation of American artists and the Italian Arte Povera group. Conservative critics were appalled by the amount of space given over to artists who shunned object making, and many on the left were as angered by what they saw as a high-handed attempt by Szeemann to make the exhibition itself the overarching artwork, exploiting the work of participating artists to make the case. Robert Morris wrote a public letter to say he was withdrawing permission to show work whose selection he had not approved, and he persuaded a group of peers to co-sign a declaration of the rights of artists to control how their work is displayed. This was published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on May 12, 1972, with a copy sent to Giancarlo Politi, editor of Flash Art, in Milan. The signatories, in addition to Morris, were Carl Andre, Hans Haacke, Don Judd, Sol Lewitt, Barry Le Va, Dorothea Rockburne, Fred Sandback, Richard Serra, and Robert Smithson. (Pictured: Letter to Giancarlo Politi, May 6, 1972).[/eob_note]Unable to travel to Germany to make final determinations and supervise the installation, he asked his friend John Knight to supervise the building of a rectangular room, including floor, walls, and ceiling, within the hallway of the Fridericianum Museum that was his allocated space, to create as unblemished and clean an environment as possible. Part of the project was to determine if the work could be delegated in this manner and still have a satisfactory outcome once built. This room was then divided in half, optically, by painting one half white, the other half black.11 Perceptually two distinct areas, but physically the same space, with no barrier between the two halves, visitors entered, as if stepping onto a stage. A visitor standing in the white half perceived an illusionistic trick, an apparent scrim closing off the black half; standing in the black half of the room did not produce anything similar. When Asher was finally able to visit the piece, in late summer, he found it “very beautifully constructed.”12 The artist did not need to have been present.

* * *

Gallery A 402, California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, California, USA, January 8–11, 1973, camera inside of installation viewing northeast into hallway. North wall painted with Sherwin-Williams Nu-White. East wall painted with Dunn-Edwards Beau-T-Wall White. Photograph by Alvin Comiter. © Michael Asher Foundation.

In the later part of 1972 Asher was invited by a group of students at CalArts to make an installation in a small public gallery they were operating on campus. This was in a small room down an out of the way corridor of the fourth floor of the new academic building. To avoid any undue reference, they had named the gallery after the room’s numeric identifier, A402. The space was unprepossessing, an office-like space with fluorescent lighting and brown carpeting, the walls painted in a typically institutional off-white. There was a desk in the corner for administrative work, and to allow supervision during opening hours. The gallery program called for a mix of local artists working in Los Angeles alongside student work in order to broaden the campus discussion of contemporary art practice.

The plan was for Asher to use the space during January of the new year. With such a short time to prepare, the proposed work was something of a low-budget reprise of both Pomona and Documenta. His first idea was to simply repaint the north and south walls of the gallery space with the Dunn-Edwards brand of paint used for all wall surfaces throughout the building, leaving the east and west walls as they were, “yellowed, spotted with fingerprints, and broken through in various places.”13 But unlike the Documenta project, he did not clearly communicate his plan, so when he arrived at the gallery to do the work he discovered that the gallery director had, in good faith, had all the walls repainted in preparation for his arrival.

Initially stymied, he took a couple of hours to think it over and came up with an adaptation of his idea. Instead of contrasting new and used, he would contrast different brands of paint, both off-white, but one formulated to diffuse light and the other intended to carry it. This would be a subtle difference, one that would task the viewer with deeply attentive looking. As a way of encouraging that act, Asher removed the desk and the double doors to A402, leaving a starkly empty white space. The removal of the doors, and the panel above them, created a framing device that heightened the viewer’s awareness of place. Coming down the hallway towards the gallery, the bright, empty whiteness of the interior space is clearly seen, and from inside the gallery, the specific, rather uncanny nature of the space is apparent in contrast to the busy-ness of the wall outside, with its water fountain, firehose, and elevator door.14

Lacking doors, the exhibit was necessarily open at all times, as was the campus. But the campus access policy was intended to encourage creative work, or at least to remove an arbitrary barrier to such work; what was the purpose of easy availability to an empty room with no door, no furniture, no markings of any kind? In his notes,15Asher talks about light, surface, tone, and value; all aspects of painting. But aside from meticulously measuring the room, he does not discuss its function, or the effect of encountering it at 2am, or 4pm. These questions he leaves in the air, to be considered by anyone willing to take the time. He would later describe this aspect of the work as “situational.”16

Later that spring Asher was hired as a replacement instructor back at UCI. At the end of the quarter, the students there organized an exhibition to include all who had participated in the Studio Problems class, faculty and students alike. It was to be a modest show in a modest space, with mostly drawings and photographs framed behind glass. For his contribution Asher measured each piece of glass used to frame work in the show, to find an average dimension, which turned out to be 14 x 14 inches, and then had a piece of picture glass cut to these measurements. His work was this square of glass, installed at eye level and attached to the wall by four finishing nails.17

Once again, the work demanded a conscious attentiveness to the materials. On one hand, the simplicity of glass and nails mimicked the presentation styles of much of the other work in the show, thus pointing to a kind of uniformity of visibility. And on the other, what was seen through the glass was the gallery wall itself, with whatever imperfections were there magnified by the lens created by the frame. So, after spending the quarter discussing the nature of art within a graduate program whose senior faculty pursued a phenomenological investigation of light and space,18 he mischievously focused attention on a section of scuffed wall.

Heiner Friedrich Gallery, Cologne, West Germany, September 4–28, 1973, west view of general office space. Photograph by Timm Rautert. © Michael Asher Foundation.

During the summer and autumn of 1973, Asher was able to travel extensively in Europe, picking up on invitations he had received from three commercial galleries following his participation in Documenta V the previous year. At Lisson Gallery in London, he isolated the floor from the walls of an unused basement space by cutting a shallow incision into the foot of the wall, all the way around the perimeter of the gallery, thus offering a subtle intensification of perception to the properly attuned visitor. A simple act of subtraction gave definition to the floor as an independent plane, a possible reference to the aesthetic formalism of Carl Andre, often described as the first “post-studio artist.”19 At Heiner Friedrich Gallery in Cologne, he took this idea a step further, having all the ceilings in the gallery—exhibition spaces, office spaces, and hallways—painted a brown/black to visually match the floor. With no signage, and again nothing on the walls, the visitor requires time to perceive the work. But once seen and understood, that visitor then follows the work into the private reaches of the gallery, including the inner sanctum of the director’s office. The documentary photographs again reveal a distinct aesthetic, a Minimalist absence. These projects in London and Cologne took relatively modest actions to communicate something about the physical structure of the gallery spaces, and in Cologne, to bring the daily work of the art business into view. At his third stop, at the Galleria Toselli in Milan, Asher took a much more radical approach. The gallery here was a large basement space within a residential compound. To quote from his notes: “At the time of the exhibit, the floor was gray concrete with a nonskid surface. The walls and ceiling were finished with numerous layers of white paint from previous exhibitions.”20Asher’s proposal was to have the walls, ceiling, and any visible hardware sandblasted to remove all traces of the white paint. It took four people four days to remove the accumulated paint and reveal the original ochre-colored plasterwork. Here, subtraction renders the space expressive, a radical kind of new beginning.

In September 1974, one year after his project in Milan, Asher completed this series of interventions in commercial galleries with a project at Claire S. Copley Gallery back in Los Angeles. At its simplest, this called for the removal of a partition wall that sheltered the gallery’s office area from public view. But Asher wanted to ensure there were no irregularities in any of the visible surfaces that might draw an attentive viewer’s eye. To accomplish this, extensive repairs were necessary on the outside as well as inside of the gallery, to fix various cracks and leaks and imperfections. The result was an immaculate, ‘as-new’ interior framing the workspace, as if it were a set for a performance work of some kind. The most familiar photograph of the piece shows two women sitting at a desk at the rear of the space, in front of near-empty bookshelves and several stacked paintings. Whereas the European projects can be seen as being in dialogue with various Minimalist artists, and require an absence to be fully visible, this work seems to rely on the implied performance of these two unnamed participants.21

Claire S. Copley Gallery, Los Angeles, California, USA, September 21–October 12, 1974, view through the gallery toward the office and storage areas. Photograph by Gary Krueger. © Michael Asher Foundation.

Claire S. Copley Gallery, Los Angeles, California, USA, September 21–October 12, 1974, view through the gallery toward entry/exit and street. Photograph by Gary Krueger. © Michael Asher Foundation.

While working on this installation, Asher was also teaching at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax and was invited to present a work at the college gallery that October. This gallery, a large open space with a glass curtain wall facing the street, simultaneously functioned as an entryway to classes and the library, and contained a desk for a receptionist. Perhaps in response to the intense labor involved in preparing the Copley gallery, this time Asher simply asked that the space be emptied and swept clean, reducing it to an empty lobby area. Students and faculty knew that the space had a history, and a name—the Anna Leonowens Gallery—and so may have found themselves wondering about what was necessary to include for an artist or gallery to declare there to be a work of art in evidence.22

Back in Los Angeles in the spring, and teaching at the Otis Art Institute, he was invited to do an exhibition in the college gallery on their campus at MacArthur Park. Finding the wall finish in the gallery unduly fussy, he decided against using it and had the gallery closed for the duration of his show. Instead, he placed small plastic letters that read, “IN THE PRESENT EXHIBITION I AM THE ART,” on the directory board in the adjoining lobby area. Just above this statement, he affixed the gallery’s mailer announcing the show. Whereas in Nova Scotia the public had been asked to consider how little actual work might be needed to raise the question of a limit to art, at Otis the focus moved to the artist. Here there was nothing at all to be seen—a show was announced, with dates and times of opening, but the gallery was closed. Instead, an easily missed declaration, on a notice board in an adjacent lobby that provided access to the upper floors of an art school, stated that the artist was the art. A cycle of installations, which quite literally tore apart the gallery space to better show how such spaces function in creating the meaning of art, ended by deflecting the process onto the artist himself, who was present in the building, as a part-time teacher.

Although this piece was minor in scale and scope, it seems to have generated a certain amount of controversy, not least in Asher’s own mind. The collection of his writings to which I have referred contains five notes written a year after the Otis installation. Returning to the question of the artist’s subjectivity, he circles around the idea that there can be no separation between the work of art and the person of the artist, meaning that the act of creation sits within the artist’s thoughts alone. In holding this idea, he is aware that it implies aspects of performance and participation: “The Claire Copley work directs perception to the gallery and the person operating the gallery. The NSCAD work directs the visitor’s perception to himself. This work directs perception to the artist; it completes the circle.”23

* * *

California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, California, USA, Faculty Exhibition, April 19–May 22, 1977, east view of installation. Photograph by Gines Guillen. © Michael Asher Foundation.

After eight years of research, proposal, and construction, interspersed with the occasional teaching job at several art schools in Southern California and Nova Scotia, Michael Asher was hired as full-time faculty in the School of Art and Design at CalArts beginning in the 1976/77 academic year. In many ways, the school, with its focus on prolonged inquiry into the nature and purpose of art, made an ideal context for Asher’s own incessant questioning, and the crit seminar the ideal vehicle. During his long tenure as a teacher at CalArts, he developed an idiosyncratic method that broke with the expected conventions surrounding class duration in order to allow an expansive discourse around student work, a discourse that could include viewing films, collective reading and discussion, along with very detailed critique of actual studio production.24 Additionally, during his first year of full-time teaching, he completed two complementary projects that can best be understood as his initial thoughts on what it means to be an artist educator.

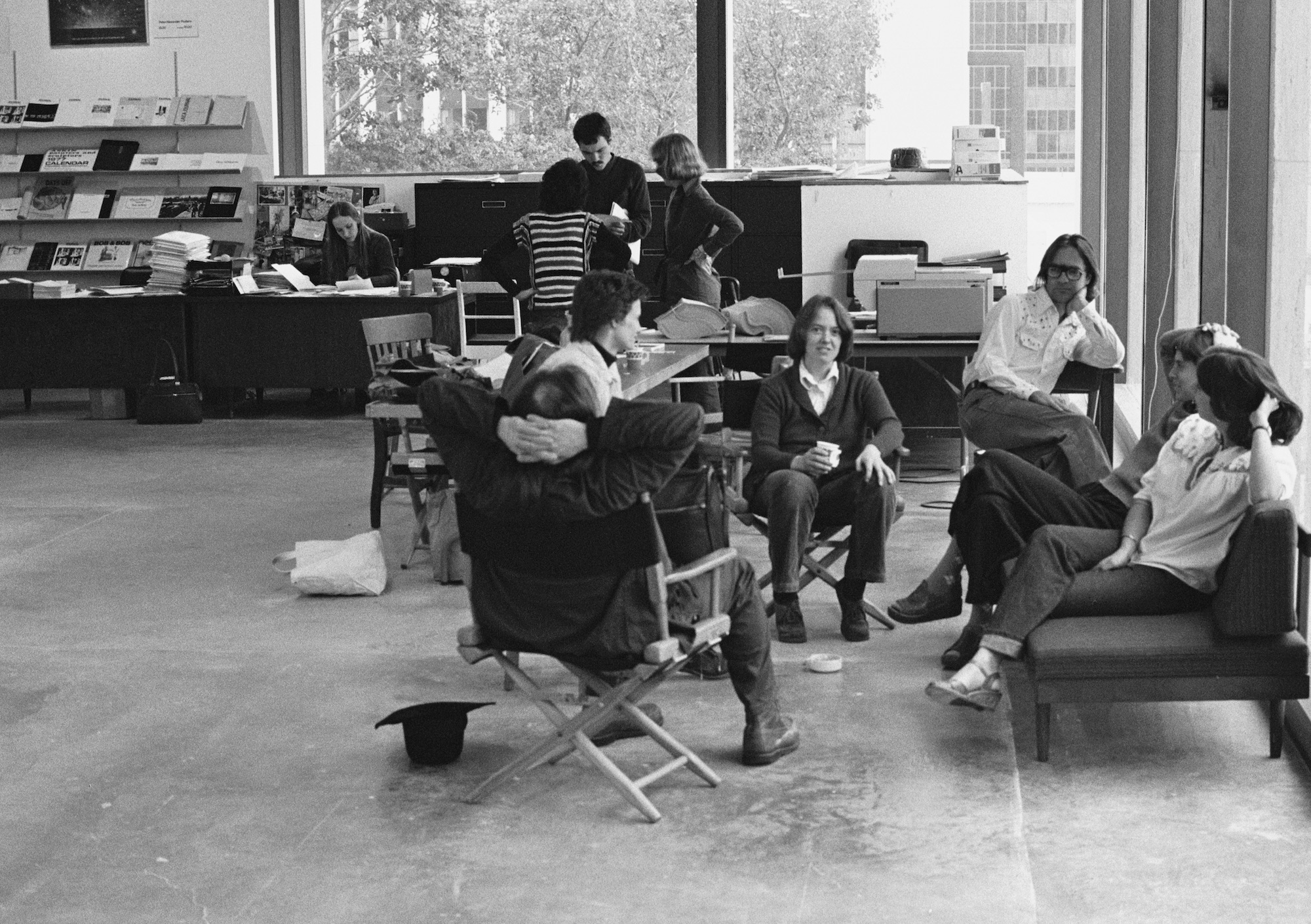

The Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art (LAICA) had been founded by Robert Smith in 1974 to support contemporary artists through an innovative exhibition program that rested on the work of visiting curators to ensure a wide range of programming. For a couple of years, the organization benefited from a nominal lease on the ground floor of the ABC Entertainment Center in Century City, but that arrangement was set to expire in early 1977. Guest curators Tom Jimmerson and Helen Lewis invited Asher, along with David Askevold from Nova Scotia and Richard Long from England, to participate in LAICA’s last show in this corporate office space. Much like the gallery at NSCAD, the gallery was fronted by a large glass wall open to the street. And again, as in NSCAD, a part of the exhibition space also functioned as a reception area with a desk and shelving. But unlike the earlier project, which was focused on an absence, this was to be concerned with presence—the main part of the gallery would remain empty, but a couch and some director’s chairs would be placed near the receptionist’s desk, where a group of six people in rotation would be paid to sit there each day that the gallery was open. In this case, the art would be the participants.

The invitees were art professionals and students and were given no direction beyond the expectation that they would show up and stay present for the entire day.25 Asher attempted to remove himself from any kind of directorial role, but as the project developed the daily meetings began to resemble a seminar, circling around questions about the nature of art, the role of the artist, and, inevitably, what Asher’s intentions were. Some participants clearly enjoyed the experience, finding it valuable to delve into the qualitative difference between process-driven artwork and the more traditional art object defined by certain formal considerations, between teasing out an idea and appreciating an aesthetic achievement. Others found this process weirdly manipulative—one woman who wrote to explain why she was withdrawing complained that she felt she was being forced into a performance as an artist enacting an artwork, which she felt took away her own agency.

Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California, USA, January 15–February 10, 1977, viewing west in installation, showing Michael Asher and participants. Photograph by Robert Smith. © Michael Asher Foundation.

Los Angeles Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, California, USA, January 15–February 10, 1977, viewing east in installation, showing group of paid participants and visitors in exhibition area and secretary at work in office/bookstore area. Photograph by Robert Smith. © Michael Asher Foundation.

This question of reification was central to Asher’s concern, as was a broader consideration of what it means to collaborate. He had moved from a focus on the physical support for art to the much thornier issue of the artist’s responsibility to the viewer, and vice versa. How precisely could an artist avoid the alienating trap of presenting an aestheticized object for approval by an audience conceived as consumers? Would creating a discursive space do this work? Must the discussion then be led by the artist, or is establishing the possibility enough? Does this deferral abdicate responsibility, putting too much of the work on the (paid) participants and any visitors who chose to join? Asher’s conclusion, transferring responsibility for a final reconciliation to the viewer, comes towards the end of his unusually long introduction to the project in his Writings:

“The LAICA installation, however, distanced work and artist by appearing to relieve me of my responsibility as author. Since the paid participants as subjects mediated the work to the viewers and to themselves, viewers were unable to personify or objectify them in the work, nor could they distance themselves from the work by means of these viewing conventions. But if the viewers were to personify/objectify the paid participants in the work, it would probably involve transforming them into either a reified theatrical spectacle or a reified aesthetic experience. This would instantly alienate the viewers from their presence as individuals… This leaves them with the responsibility which, in traditional aesthetic practice and perception, was deferred to either author or object.”26

Several months later, and still working through this question of the position of the artist, he agreed to participate in a double, year-end show at CalArts, one that would include both faculty and students. The set-up gave him the opportunity to extend his inquiry into the role of the teaching artist. Planned for the large central hall called the Main Gallery, the student work was to be hung on the main floor, with the faculty on the encircling mezzanine above. Uncomfortable as yet with taking on the identity of faculty, he positioned himself as primarily an artist working outside of the institution, an invitee of sorts. His solution was to have a small hole drilled into the center of each of the four planes that created a visual separation between the two exhibition areas, with a small pad displaying a diagram of the work placed nearby.27The work sounds almost invisible, but its audacity, Asher’s refusal to accept institutional norms, made it highly present. In his project at Otis, he had declared himself the art; at LAICA, he had apparently deflected the task to either his paid collaborators or to any members of the public willing to volunteer their attention. In this oscillation he posited the idea of artist as interlocutor, a figure at something of a remove, posing questions but offering no answers. At CalArts he tested the proposition that an artwork designed with pedagogical intent could still have real world validity. In his continuing work as a guide and teacher, he would insist that his students put their work to that same test.