Not a Condition But a Process

by Thomas Lawson

California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) co-published Afterall from 2002-2009. This essay was originally published in Afterall 11, Spring/ Summer 2005. All original formatting has been preserved.

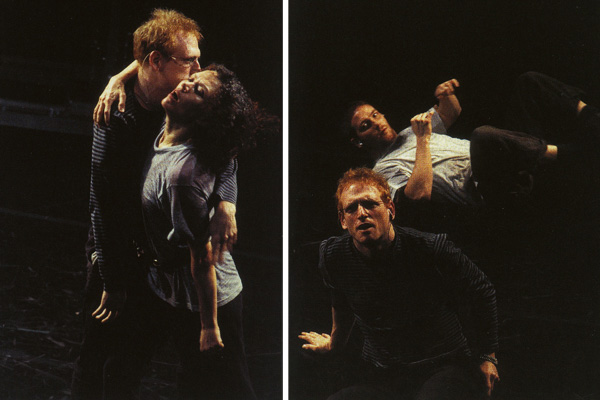

The Wooster Group, Poor Theater (Simulacrum #3), 2006. Directed by Elizabeth LeCompte. Pictured: Scott Shepherd, Kate Valk, Ari Fliakos. Photo: Paula Court.

Why are we concerned with art? To cross our frontiers, exceed our limitations, fill our emptiness – fulfill ourselves. This is not a condition but a process in which what is dark in us slowly becomes transparent. – Jerzy Grotowski1

I open with this idealistic statement of art’s purpose by way of indicating that we are in a period of strange contradiction. The phenomenon of contemporary art seems to be thriving, on a global scale unimaginable 20 years ago. But under that veneer of success there lurks a suspicion that something is missing, a vital connection to the everyday matters of life and death. It is very apparent that, despite widespread anger that we are waging war in Iraq, we are not reliving 1968, when artists sought to express their outrage at the war in Vietnam by claiming the role of conscience. That moment itself may be ridiculed as a period of neo-avant-gardism, a pale reflection of the genuine article, the heroic revulsion from the very idea of art expressed by the Dadaists in 1917. But the generation of ’68 clearly sought to lay out new conditions for the meaning and reception of art. Boundaries were tested. The idea of relevance was given urgency. Today, in this seemingly a-historical moment in which nakedly expressed will is seen to trump process and persuasion, the practice of art seems strangely un-moored and artists randomly ransack the past for pieces of formal gold to entice what seems to be an ever expanding market.

After the exuberant experiments of the late 1960s and early 70s, there began a long period in which all the various parts of the art world sought to reshape and rethink the parameters of the possible, what might count and what could not. It is arguable that an important element in the development of new art in the 1970s in New York – variously and inadequately identified as pictures art, appropriation art, art made under an allegorical impulse – developed in response to the experimental theatre work that appeared in the late 1960s and developed in strength and presence throughout the next two decades. In the foreground of this wave of experimentalism are two director/playwrights, Richard Foreman and Robert Wilson, and two collectives, Mabou Mines and The Performance Group. The latter was founded by Richard Schechner in 1967 and served as a base for a group of artists who began to produce their own work in 1975 under the direction of Elizabeth LeCompte, and who, in 1980, became the Wooster Group.

The theatre work of the Wooster Group has always been intensely visual. Typically the stage of the Performing Garage is laid open to view as the audience enters the theatre; there is no proscenium, no curtain, apparently no illusion. There before your eyes is a field of technology: multiple video monitors, control decks, cables, microphones, speakers; the paraphernalia of spectacle. In a sense the stage is laid out to represent an artist’s studio, a workshop where images and texts are to be viewed, analysed, worked on and up, reframed, cut and pasted, re-broadcast. The work of LeCompte and her actors is visual, but also inextricably bound to language. Extraordinarily original, it is nevertheless based on various confrontations with pre-existing texts, from O’Neil to Stein at the high-end, to cheap porn and silly Westerns at the other. Such texts are read closely, pulled apart, re-ordered, pushed up abruptly against each other. This is active reading, reading as questioning. Nothing is sacrosanct, but the idea that there must be something meaningful to be found in the cacophony of modern life.

At a moment when the redefinition of art practice characteristic of the late 1960s – the repudiation of representation, narrative and metaphor – had pushed the possibilities of art making to its limits, The Wooster Group appeared to offer a way forward by incorporating these forbidden elements within a presentation that was clearly deconstructivist in spirit. Here was a self-consciously foregrounding technique, pitting ideas of good and bad, appropriate and inappropriate methodologies against each other in an essentially editorial process designed to reposition and reframe existent material taken from the culture at large.

LeCompte began her directing career in 1974, while still an assistant to Schechner, who, following the Polish avant-gardist Jerzy Grotowski, had been seeking to break down the barriers between art and life, performance space and audience space, in the hope of discovering a ritualistic theatre that would lay bare and transform the psyches of all performers and spectators alike. This was an improvisation-based theatre, requiring intensive physical and emotional training. In tune with the imperatives of her own generation LeCompte came to find it heavily symbolic and dangerously psychoanalytical. Thinking there was not enough filtering in the process she began to explore anti-naturalistic gesture, non-linear structure, and various forms of visual language in an attempt to introduce a certain distance to the work, a lens that would allow a more critical inspection on the part of the audience. The work she began producing consistently placed the present tense against the past as it juxtaposed documentation and analysis, observation and memory, biography and history. Here was someone uncompromising in her willingness to confront real topics about the difficulty of life, and interested in using a range of performance and presentation techniques to get there.

The core of the theatre is an encounter. The man who makes an act of self-revelation is one who establishes contact with himself. That is to say, an extreme confrontation, sincere, disciplined, precise and total – not merely a confrontation with his thoughts, but one involving his whole being from his instincts and his unconscious right up to his most lucid state. – Jerzy Grotowski2

The Wooster Group, Poor Theater (Epilog), 2006. Directed by Elizabeth LeCompte. Pictured: Scott Shepherd, Sheena See, Kate Valk, Ari Fliakos. Photo: Paula Court.

Beginning the development phase of Poor Theatre: A Series of Simulacra, (first performed in early 2004) LeCompte returned to the roots of her work, revisiting Poland to begin a reconsideration of Grotowski, and by implication, the whole modernist assertion of the critical importance of presence. Who was Grotowski? He was a producer/theorist who, in 1959, created a small experimental company, The Theatre Laboratory, in a small town in south west Poland, which he moved to Krakow in 1964. Working with a permanent troupe of performers, in close contact with a number of psychologists, linguists, phonologists, anthropologists, and other intellectuals working in the academic disciplines that seek to understand human culture, Grotowski exploited his isolation from mainstream culture in order to reject the conventions of theatre as they were understood at that time, and instead plunged into an investigation of the very nature of theatre and the art of the actor. Despairing over the condition of Western culture at a time when the technologies of mass media were beginning to assert their ability to blind all under the glare of spectacle, Grotowski sought the essential means by which his art could continue to function as an outpost of rejection. Identifying the problems of the mainstream art forms, which he called ‘rich theatre’ his analysis is acute: ‘Rich Theatre depends on artistic kleptomania, drawing from other disciplines, constructing hybrid-spectacles, conglomerates without backbone or integrity … By multiplying assimilated elements, the Rich Theatre tries to escape the impasse presented by movies and television. Since film and TV excel in the area of mechanical functions (montage, instantaneous change of place, etc.), the Rich Theatre countered with a blatantly compensatory call for “total theatre”. The integration of borrowed mechanisms (movie screens on stage, for example) means a sophisticated technical plant, permitting great mobility and dynamism. And if the stage and/or auditorium were mobile, constantly changing perspective would be possible. This is all nonsense.3

To correct this Grotowski proposed a ‘poor theatre’ in which he sought to eliminate everything superfluous. He discovered that theatre can exist without make-up, without costumes and sets, without a stage, without lighting and sound effects. What it cannot exist without is a text and the actor-spectator relationship, which he saw as an act of direct communion. For Grotowski theatre became identified as an encounter – between producer, director, text, actors, and audience – an encounter between creative people, across time. He described this as ‘a brutal and brusque confrontation between on the one hand the beliefs and experiences of life, of previous generations and, on the other, our own experiences and our own prejudices.4

In 1964 Grotowski developed a new work, Akropolis, based on a late nineteenth century text by the poet Wyspianski. The original is a kind of pious Tam O’Shanter, set in Krakow cathedral on the eve of the end of time, only here, instead of witches dancing crazily, the first person reporter observes the artwork in the cathedral come to life in order to act out the great moments of Western history and culture. The idea is to present a valedictory to civilization, a kind of final test of its values. Grotowski takes this post-romantic paean and turns it into a tool to interrogate Poland’s complicity in the Holocaust, replacing the cathedral with a concentration camp, and the figures of art history with the lost inhabitants of the camp. There are no sets, only a number of selected objects, each of which must contribute to the play’s dynamics. The actors play stereotypes, each identified by a mask he has composed by contorting his facial muscles. Each wears this grimace for the entire play, moving his body as though in pantomime, and using his voice to speak, but also to babble, groan, chant, declaim, make animal noises, sing snatches of folksong. The original text is torn apart, reduced to repeated phrases and inchoate screams and groans. Everything depends on the virtuosity of the performer’s ability to maintain a fully credible presence, intense enough to elicit a reaction of recognition from the audience sitting a few feet away. This was a theatre of violent intimacy.

Collage is the meeting of two distinct realities on a place foreign to them both. – Max Ernst5

LeCompte saw the Grotowski piece as it was originally staged, and Poor Theatre: A Series of Simulacra is her reconsideration of what this formative piece means now, and what it means in regard to her ability to continue working. Poor Theatre is framed as an investigation into the possibility of art making, and is structured around the probing of two sources: the performance theories of Grotowski and those developed by American choreographer William Forsythe. Both are experimentalists interested in stripping performance to its basic elements in order to achieve a more direct expression of an emotional truth. Both question the procedures of art as a way of getting to the essential question, why do it? But although equally radical, they are separated by the historical shift away from Modernism. Grotowski’s question is framed as a version of post World War II modernist essentialism: he earnestly needs to know if it is possible to make art after the Holocaust, and, assuming it is, wants to investigate how. In pursuing that investigation he realises that the greatest challenge facing the artist is posed by mass media, and he begins to consider ways to confront that. Forsythe, barely 12 years later, has to deal with the failure of a previous generation’s existential protest while acknowledging the ever-greater reach of the media, that is to say, how to strike a balance between a frenzied self-importance and the emptiness of technologically driven spectacle. Grotowski was seeking elemental truth; Forsythe approaches the question with irony-tinged skepticism, producing forms that elaborate on their meaninglessness.

Looking into the dark mirror of various shared histories, LeCompte struggles against amnesia. The reconsideration of her past thus becomes a (re)generative act, which, in its abrupt collisions, jolts the audience to consider correspondences and disparities. The Grotowski section is very serious, an archive driven search for beginnings. The Forsythe section is comedy, with the dancer’s instructions used to stage an absurdist shoot out.

The development of the new work involved the cast visiting the preserved studio in Krakow, watching a video of a film of one of the original performances, as well as videos of the early Performance Group works inspired by Grotowski, in order to come to an understanding of the ideas and begin the task of recreating the performance. Thus the piece develops out of a series of potential misreadings, of the poorly lit film, of the original play, in Polish verse, translated into English prose with the help of a computer program. As it plays out the first act presents a nesting series of reduplications that demonstrate the difficulty of acquiring any understanding, let alone mustering the will to do something with it. An outline of the original studio is mapped out on the stage floor, a centrally placed video monitor shows an interview with Grotowski together with selections taken from the film of the original performance, while on stage the actors re-enact a meeting they had with a theatre historian in Poland, and then, in an extraordinary feat of mimicry, the actors stage, in a facsimile of Polish, a replica of the scene from Akropolis that we have just seen on tape. Stunned by the magic of theatrical illusion we find ourselves paying homage to the sincerity of Grotowski while simultaneously acknowledging the absurdity of his passion.

To translate this back into the realm of visual art one might consider the photographed reconstructions of found photographic imagery undertaken by Thomas Demand. In a recent essay on this work Michael Fried begins by quoting the curator Roxana Marcoci as she describes the artist’s procedure. She writes, ‘As a rule, Demand begins with an image, usually, though not exclusively, from a photograph culled from the media, which he translates into a three-dimensional life-size paper model. Then he takes a picture of the model with a Swiss-made Sinar, a large-format camera with telescopic lens for enhanced resolution and heightened verisimilitude.6It is the care taken, and the quality of the tools used, that together conspire to complete the illusion that we are seeing a picture of the real thing, not its simulacrum. The commonplace interpretation of this work is that it turns a jaundiced eye on the idea of photographic truth, and no doubt it does do that. It is also spookily empty of life; although based on photographs of newsworthy spaces, crime scenes of one sort or another, human presence is reduced to the nearly imperceptible, but fully deliberate imperfections – the stray pencil mark or wrinkle – that bring us back to the mechanisms of art making. As Fried brilliantly argues, ‘[Demand] aims above all to replace the original scene of evidentiary traces and marks of human use – the historical world in all its layeredness and compositeness – with images of sheer authorial intention.7

An alphabet of movement is formed by a collection of 26 series of abstracted gestures, manipulations and other imaginary actions. For each letter of the alphabet a word can be invented, predominantly names, verbs, nouns and adjectives. With each word comes a movement … There quickly arises an associatively connected family of 26 “danced words”. – William Forsythe8

The second act begins with the video monitor again. This time we are being guided through a confusing maze of corridors and staircases, seemingly looping up and down, back through doors already entered in an increasingly manic search for resolution. Our increasingly breathless guide, an actor inhabiting the persona of the dance theorist and long time director of the Frankfurt Ballet, William Forsythe, is earnestly explaining how he wants to show us something, how difficult it is to do that without support, and how he feels he is losing it, entering into a condition of anxious freefall. The actor on screen then steps onto the stage and, standing behind a lectern, begins to give a complex lecture on the nature of movement. As he speaks, the other members of the company join him on stage and, creating a tableau vivant backdrop to this somewhat academic-sounding exercise, begin demonstrating the moves in a parody of modern dance that is also an absurd game of pretend in which a Western shoot out is mimed.

One of Forsythe’s favourite methods is a contrapunctal composition that depends on variations in timing and phrasing enlivened by abrupt changes in direction, a kind of animated jump-cut that pulls asymmetries out of harmony. He had originally studied classical ballet at Julliard in the early 1970s before leaving New York for Europe in search of an environment that would nurture his art. He soon found that support in The Netherlands and Germany and by 1984 he became artistic director of Ballet Frankfurt, and was able to use that position to develop his interest in the grammar of movement into a deconstructivist choreography. (The irony implicit in the video segment is that in the past year Frankfurt has declined to continue its financial support of his company, thus this abstract musing on the possibility of art also touches on the practicalities of that question.) Fascinated by the shifting perspectives and proportions found in cartoons, the rapid cuts and violent segues, he created compositions without a centre. Instead a repertory of movements is created, analysed, taken apart and rearranged – movement cut and pasted just as text in a word processing program. These simplified movements build against each other to create complex layered constructions that play out over the duration of the performance. Space is mapped over time.

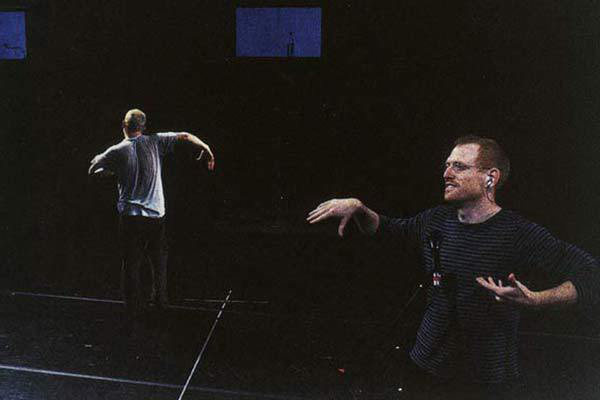

The Wooster Group, Poor Theater (Simulacrum #3), 2006. Directed by Elizabeth LeCompte. Pictured: Scott Shepherd, Ari Fliakos. Photo: Paula Court.

The encounter proceeds from a fascination. It implies a struggle, and also something so similar in depth that there is an identity between those taking part in the encounter.-Jerzy Grotowski9

The problem with the call for art to be solely concerned with drawing attention to authorial intention is that success then depends on a world of stable referents against which such intentionality can be measured. The modernist collage, be it physical or conceptual, rests on a coherent world as it draws attention to the space between incommensurate realities. In Art After the End of Art, Arthur Danto describes how, in a cultural landscape no longer dominated by categorical thinking, the willed collision of unknowns is no longer a possible source of creative conflict. Contemporary experience, with its quotidian slipperiness, has rendered the sense of otherness itself other. Intellectually, we are all creole; everything is deterritorialised, and thus everything and anything is thinkable, a condition that bleeds the urgency from the encounter of otherness, and replaces it with the marriage of similarities. Poor Theatre examines this paralysis of permissions by presenting a series of interlocking re-duplications within the painter’s structure of the diptych, its two parts mirroring each other across an almost unnoticed entre’acte. A meditation on the floor of Grotowski’s studio, as remembered from a visit, undertaken in the spirit of pilgrimage, when the artist was young, is framed by a consideration of Max Ernst’s technique of frottage. Reflection is thus refracted through an indexical record of the facts. But Ernst’s method was not designed to be merely a direct method of representation; he was more interested in using these captured shards of reality to capture a more mysterious truth. The detail may be true, but it becomes invested with some other meaning that is much harder to validate.