One Classic, One Modern: The Brief Correspondence of Roberto Bolaño and Enrique Lihn

by Annette Leddy

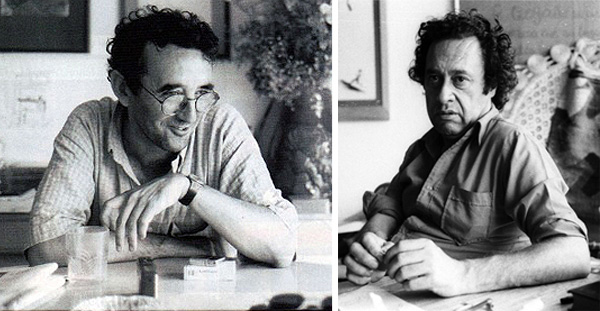

Left: Roberto Bolaño, date unknown. Right: Enrique Lihn, Santiago, 1983. Photo: Marcelo Montecino.

The papers of Enrique Lihn, the late Chilean poet, novelist, playwright, and critic, came to rest some ten years ago in the chilly vaults of the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. Within these multiple enclosures lie a few pieces of correspondence from the author Roberto Bolaño, who was then in his late twenties and living in Gerona, Spain.1 Bolaño references these letters in “Meeting with Enrique Lihn,” a short story in which the narrator (“Roberto Bolaño”) describes a brief period of correspondence with one of the few Chilean authors he admired:

[F]or a time, a short time, I had corresponded with [Lihn], and his letters had, in a way, kept me going; I’m talking about 1981 or 1982, when I was living like a recluse in a house outside Gerona with practically no money and no prospects of ever getting any, and literature was a vast minefield occupied by enemies, except for a few classic authors (just a few), and every day I had to walk through that minefield.2

He goes on to describe his own letters to Lihn as being about “my life, my house in the country, on one of the hills outside Gerona, the medieval city before it, the countryside or the void behind. I also told him about my dog, Laika, and said that in my opinion, Chilean literature, with one or two exceptions, was shit.”3

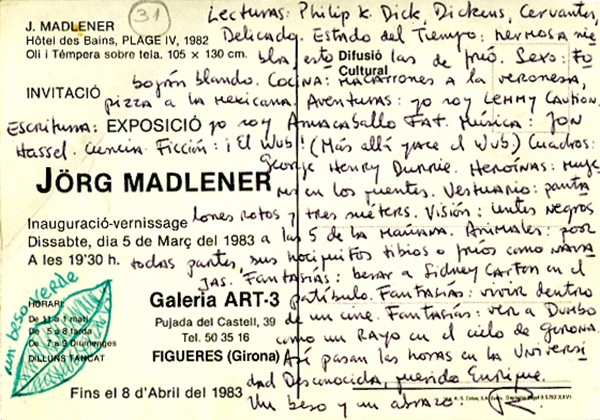

Though the actual correspondence does touch on all these topics, it also contains, like most correspondence between writers, lists of what the author is reading, looking at, and listening to. One postcard in particular communicates the “few classic authors” who are sustaining Bolaño through his extended period of working unrecompensed and unrecognized, on the threshold of living with the woman he would marry in 1985, and with whom he would have two children. 4For the sake of these children he would turn from writing poetry to writing fiction that would earn him acclaim commensurate with his highest aspirations.

Weather condition: Beautiful fog, stoles of cold

Sex: Soft toboggan

Adventures: I am Lemmy Caution

Writing: I am Horselover Fat

Music: Jon Hassel

Science Fiction: ¡The Wub!

Heroines: Women on bridges

Vesture: Torn pants and three sweaters

Vision: Sunglasses at 5 in the morning

Fantasies: To kiss Sidney Carton in the gallows

Fantasies: To see Dumbo like a ray in the sky of Gerona

Postcard from Bolaño to Enrique Lihn, 1983. © Robert Bolaño, used with the permission of The Wylie Agency and the Getty Research Institute.

These entries are evocative in their specificity, while to follow up on the cultural references is to enter into a dense network of associations that converge in similar themes. This assembly of references presages in skeletal form the digressive style of Bolaño’s novels. They also anticipate his characteristic fusion of plot with reformulations of the canon.5The first of this kind of entry refers to literature:

In an interview a year before his death in 2003, Bolaño made a statement that suggests a way of connecting these four disparate authors: “I’d like to be a writer of the fantastic, like Philip K. Dick, although as time passes and I get older, Dick seems more and more realist to me. Deep down … the question doesn’t lie in the distinction of realist/fantastic but in language and structures, in ways of seeing.6

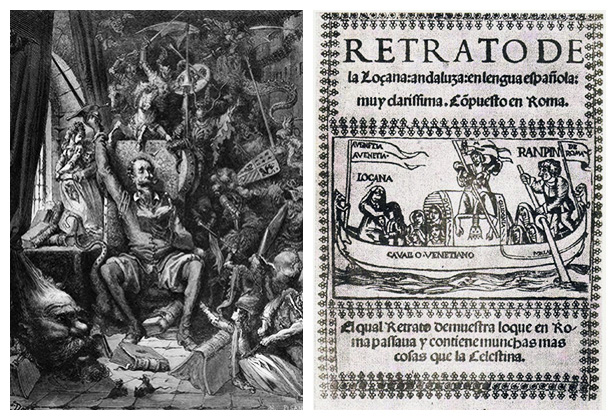

The structures and ways of seeing these authors’ works share would seem to be those of the picaresque novel, typically defined as a narrative about an antihero traveling through a corrupt world or a world gone mad. We may assume that the book by Francisco Delicado he is reading is the only novel by the author that survives, Portrait of Lozana: The Lusty Andalusian Woman (1523), a kind of Renaissance Moll Flanders in which the protagonist becomes the madam of a brothel in Rome, and through her eyes the decadence of the Holy City is revealed. By Cervantes he was perhaps reading the book that he named when, at the end of his life, he was asked which five books had most influenced him: Don Quixote (1605), a work that, like Delicado’s, is often called the first novel.

Left: Illustration of Don Quixote (1605) by Gustave Doré. Right: Cover page from the first edition of Francisco Delicado’s Portrait of Lozana: The Lusty Andalusian Woman (1523).

Bolaño’s grouping of disparate works about tyranny and corruption on the one hand, and mad heroism on the other, conjures, among other sociological theories of literature, György Lukács’s Theory of the Novel, a work Bolaño probably would have encountered during his years as a leftwing literature student, though he doesn’t mention it as an influence. According to Lukács, Don Quixote was the first work to show the challenge of writing a narrative in which the destiny of a community and of the hero are not identical, as in the epic. Rather, “the purest heroism is bound to become grotesque, the strongest faith is bound to become madness, when the ways leading to the transcendental home have become impassable.”7

Two novels by the other cited authors would seem to define as their very themes this challenge of how to be heroic in a “period of demons let loose, a period of great confusion of values.”8Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities (“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness”) begins by evoking this conflict of values as one of perception. Dick’s VALIS (Vast Active Living Intelligence System) portrays contemporary California as a place where that perception is a matter of psychology: “This time in America—1969 or 1970—and this place, the Bay Area of Northern California, was totally fucked. … The authorities became as psychotic as those they hunted.”9

Certainly, one way to render a fragmented world is to exemplify it in the protagonist’s psychology, or as Lukács puts it, “the fundamental form-determining intention of the novel is objectivised as the psychology of the novel’s hero.”10Thus, Dickens’s character Sydney Carton and Dick’s Horselover Fat each have a double. The brilliant but dissipated lawyer Carton closely resembles the heroic character Charles Darnay; when Carton arranges to be guillotined in Darnay’s place, he becomes his heroic double in both pretense and in spirit. Presumably this is the moment to which Bolaño refers with the following entry:

In a more current avatar of this divided-self theme, the mentally deranged and drug-addicted Horselover Fat in VALIS merges with the cool, lucid narrator “Dick” when together they receive the cosmic wound-healing wisdom. Bolaño has taken this mad double into himself:

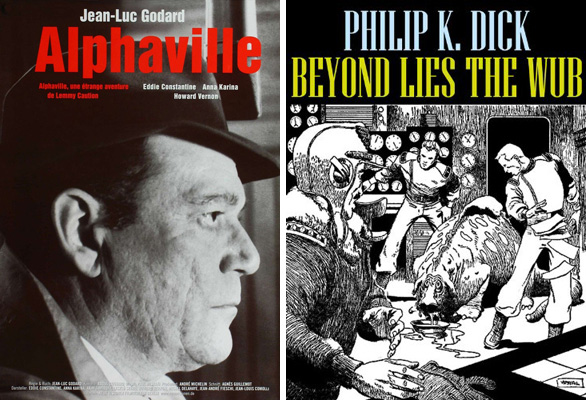

Other works the postcard refers to concern a treacherous confrontation with a despot who is an evil antithesis of the hero:

Science Fiction: ¡The Wub!

Adventures: I am Lemmy Caution

Left: Poster for Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965) showing the character Lemmy Caution. Right: Cover illustration for Phillip K. Dick’s short story, “Beyond Lies The Wub” (1951).

In Dick’s short story “Beyond Lies the Wub,” the wub is a telepathic pig from Mars of exceptional erudition and sensitivity. A brutish spaceship captain presumes to kill and then feast on the wub, only to be taken over by its mind and spirit, which telepathically continues a conversation about The Odyssey he was having with another character before he was eaten. Lemmy Caution, the protagonist in Godard’s film Alphaville, battles a computer, Alpha 60, who has outlawed love and other emotions on his planet. Caution triumphs partly by confusing his nemesis with poetry, something Alpha 60 can’t fathom.11But, strangely, Alpha 60 is literary enough to quote Borges, the first Latin American fiction writer to deploy pulp (pop) culture in the service of metaphysics.

Borges, Julio Cortázar, and Adolfo Bioy Casares are often named as Bolaño’s literary predecessors, just as surrealism is identified as his true tradition.12The items on the postcard that most support that argument are those about the mind-altering revelation that madness or drugs evoke. The above-cited Horselover Fat, for example, receives revelations about cosmic trauma in a pink laser light of hallucination. When Bolaño defines himself as a writer like Horselover, he presumably refers to the sensation of writing as the surprising reception of messages or ideas. Other entries also indicate this side of Bolaño’s work:

Fantasies: To see Dumbo like a ray in the sky of Gerona

Dumbo after he learned to fly. From Dumbo (1941).

In the Disney film, Dumbo has a revelation when he gets drunk and imagines the dance of the pink elephants and ends up in a tree, thereby realizing he can fly.13Jon Hassell, composer of what he termed “fourth world” music (a combination of traditional folk and electronic techniques), refers, in works like Dream Theory in Malaya (1981), to revelations from the unconscious. This album was Hassell’s response to anthropological studies about dream-telling in the Senoi culture, where, for instance, a child’s dream of falling was praised as a gift that would help him learn to learn to fly in his dreams the next night.14

What this postcard suggests is that, for Bolaño, messages from the unconscious and even chance operations profit from their fusion with aspects of the picaresque novel, or the epic-in-a-minor-key, from which he apparently drew lessons in literary structure and also a sense of collective values that is manifest in the political content of his best work. This observation correlates with the author’s insistence that the epic is still a viable form, but not in its realist manifestation.15

In Bolaño’s fiction, as in Borges’s, the writer is the hero, to a great extent because he takes up the terrible struggle that Lukács defines as that of giving accurate representation to an infinitely incoherent totality. The picaresque or parodist aspect of many of the stories Bolaño began writing in Spain involves the petty networking required of the aspiring writer with no connections: entering obscure literary contests that offer paltry prizes, attending parties with rivals one dislikes, and writing letters to impress the very few writers one admires, like Lihn. On this particular postcard, Bolaño listed off movies and books probably absorbed over several years as if he were reading them all at once—perhaps so as to quickly define his aesthetic without using up too much of the literary elder’s time and patience. These demeaning efforts, Bolaño’s fiction asserts are, like battling windmills, the heroic adventures of today’s antihero-writer, most hilariously in “Henri Simon Leprince,” his story of an unsuccessful writer who becomes an underground fighter in the French Resistance.16While risking his life to help literary celebrities to safety, when huddled, for example, in a dark tunnel, Leprince gets advice on publication and possible paths to advancement. Thus does valor meet literary ambition.

“Meeting with Enrique Lihn,” written some 15 years after the postcard, tells of a dream the narrator, “Roberto Bolaño,” has of meeting Lihn in a bar, though the dream takes place after Lihn’s death from cancer, and in the

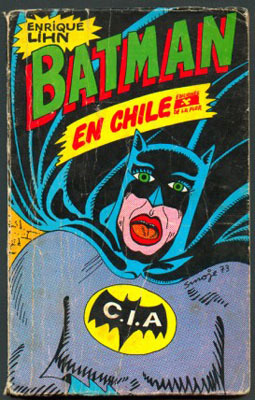

Cover illustration for Enrique Lihn’s novel, Batman En Chile (1973).

dream Bolaño endures the paradox of knowing Lihn is dead while knowing he’s meeting him. After being threatened by a hit man in the street outside the bar, and tricking this ominous double into leaving him alone, Bolaño goes with Lihn in the elevator up to Lihn’s apartment, which has a glass floor from which Bolaño can observe everything going on in the bar downstairs, and which is filled with fragile objects, including two books: “one a classic, like a smooth stone, and the other modern, timeless, like shit.” 17

Both Lihn and Bolaño succeeded in fusing classic literature with “shit” (pulp). Lihn’s novel Batman in Chile (1973) even parodied left-wing paranoia about the imperialist effects of American popular culture.18Bolaño’s story ends with Lihn’s disclosure that the “tigers are finished” and that the two of them are in the realm of the dead. At this point Bolaño may have known he wouldn’t live much longer, but he already knew that, like Lihn, he was one of the tigers of Chilean literature. He had made his way through the minefield (perhaps represented by the hit man), and would join his mentor, along with other writers on his short list, in the afterlife of literary heroes.

The postcard concludes with a reference to what would one day be the title of one of Bolaño’s poetry collections:

Like this pass the hours at the Unknown University, dear Enrique