Options, Not Solutions

by Michael Ned Holte

California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) co-published Afterall from 2002-2009. This essay was originally published in Afterall 15, Spring/Summer 2007, and is reprinted with permission from the author. All original formatting has been preserved.

Richard Hawkins, Mostly Pink, 2000. Oil on canvas, 24 x 30 in. All images courtesy of Richard Telles Fine Art, Los Angeles.

In the November 2000 issue of Artforum, Richard Hawkins concluded his ‘Top Ten’ list — which included everything from Robert Altman’s 1977 film Three Women (number 6) to ‘Good stuff on TV this summer’ (number 2) — with a rave for ‘Any painting made without using masking tape’, immediately followed by this zinger: ‘If the masking tape factory burned down, there’d be no painting in LA for at least a season.’ If you were cruising the galleries in southern California circa Y2K, you’d know he was hitting below the belt. Ouch.

Hawkins’s jab was personal. Approaching the millennium, the Los Angeles-based artist had, almost unexpectedly, started making paintings — painterly paintings, with brushes, oil, canvas, etc. — after gaining some acclaim, and perhaps a little notoriety, in the previous decade for a body of seemingly off-hand, but genuinely unsettling work: objects of desire — presumably the artist’s — extracted from mass media and subjected to erotically-charged, frequently violent treatment that one could safely refer to, for the sake of tradition, as ‘collage’ (or perhaps ‘assemblage’). For example: Hollywood hard rockers cut from magazines and casually paper-clipped to latex ribbons of slashed Halloween masks (Poison, 1991) or to the margins of large sheets of coloured felt (Captive, Blue, 1993); inkjet prints incorporating images of a young, shirtless Matt Dillon or Dazed and Confused’s androgynous stoner-in-training Wiley Wiggins against mildly psychedelic, primitive digital backgrounds (med.pink.matt.graveyard and med. yellow.wiley.classroom, both 1995); large inkjet prints of disembodied and bloody ‘zombie’-fied (via Photoshop) heads of young, male actors floating in front of pretty pastel grounds (disembodied zombie guy peach, 1997, among others), etc.

In 2000, Hawkins exhibited a series of petite canvases at Corvi-Mora gallery in London. The paintings were tentative, even polite, but also unmistakably painterly, unabashedly colourful and ‘abstract’. (Reviewing these paintings in frieze, Alex Farquharson noted, ‘their physical presence is miles away from the New York School, although they take on a kind of Ab-Ex appearance in reproduction’, appropriate for an artist who had spent so much quality time with his nose in magazines.) As if to ease the transition into abstraction — and, in a bigger sense, from pointedly ‘artless’ to unavoidably art-like — the paintings were accompanied by framed magazine pages of male models casually decorated with ejaculate-like daubs of coloured paint. If one were carefully tracking the development of the collages — the recent splatters; the trippy inkjet grounds; the Gustave Moreau inspired, Salomé-like severed heads — one might have seen painting coming. And as coming. That is, as the (inevitable) outcome of all that desire. Masking tape, needless to say, was not welcome at the party. Adamantly handmade, these little paintings feature layered assemblies of rectangles tweaked into rhomboids in gorgeous, high-key colours, occasionally punctuated by flat, uncut black and a variety of carefully errant marks and brushstrokes. Many of the titles — mostly red & orange; orange, upside down; mostly green with yellow (all 2000) — are perfunctory and reveal little that isn’t readily apparent; others — including mostly pink (2000), which is just as red as it is pink — present subtle disinformation. Either way, the titles simply ask you to look at the paintings (again). Some of the rhombi drip like leaky containers. Indeed, some are delineated but not fully filled in, as if they are being drained, not unlike the earlier oozing disembodied heads. Amid so much death-of-painting claptrap at the time, Hawkins’s colourful, corporeal zombies were lurching onward.

By 2003 Hawkins’s paintings, while still small, had clearly evolved within a few short years. On the one hand he was making lusher, looser, brushier works — including Not Velvet (purple), Moonlight and many untitled — that adopted the darker tones of bruises, rotting fruit (or flesh), sticky liquors and dying embers; on the other hand, he was making a series of rigorously controlled, even self-consciously ‘tasteful’ (and still subtly ‘painterly’) paintings — including Bulletin, Orange Caboose, The Pencil of Nature — each featuring a handful of circles carefully arranged on a mostly monochromatic, vertical ground. In Pink Caboose these approaches were combined. One could see Hawkins, in his delirious search for aesthetic equilibrium, as a contemporary version of Duc Jean Floressas des Esseintes, the decadent anti-hero of Joris-Karl Huysmans’s 1884 novel À Rebours (Against Nature). In that perversely brilliant tale, des Esseintes hires a lapidary to cover a live tortoise’s shell with extravagant, artificial gems — in order to offset the brown colour of his rug. The tortoise, unsurprisingly, dies from the experiment. Unlike the reclusive des Esseintes, Hawkins conducts his experiments in public — for an often ferocious audience. And, unlike that character, Hawkins has yet to kill the proverbial tortoise, though on occasion he has come close.

Richard Hawkins, Stumps, 2004. Acrylic and oil on canvas, 30 x 40 in.

Take Plane of Immanence (purple) (2003), an ungainly attempt to paint readily identifiable subject matter — in this case a table, crudely described with a thinly painted line. The tabletop is a trapezoid that fills much of the frame; the top of two table legs are shown at the bottom corners of the picture. Everything is mottled on the surface, with low-contrast tones of pink and violet: the table emerges precariously, a little ghostlike, from the field. Reminiscent of the Caboose series, six impastoed circles in deep reds and plum browns are situated on the tabletop — or are they simply floating dumbly on the surface of the picture itself? Given the awkward perspective, no easy answer is forthcoming. That unresolved tension is seemingly the point: the weird sense of space refers at once to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s ‘plane of immanence’ — a conceptual ‘event horizon’ that precludes the finality of transcendence in favour of perpetual ‘becoming’— as well as Clement Greenberg’s ‘flatness’; Philip Guston’s ham-fisted, blushing pink brushstrokes; the chromatic sameness of Giorgio Morandi’s still lifes; and Leo Steinberg’s characterisation of Robert Rauschenberg’s combine paintings as ‘flatbed’ pictures, among other distinct possibilities.

In short, the perspective mediates the horizontality of the ground (mimicked by the tabletop) and the verticality of the canvas ‘ground’ — and all of the art-historical maneuvering that 90-degree twist implies. Despite its lack of elegance Plane of Immanence (purple) seems to suggest a ‘eureka’ moment for Hawkins, who followed with a series of still lifes — including Cargo Cult, Telstar, The Promise of Industry (all 2003) — mostly similar, largely pink, with the impasto circles of Plane… transformed into cartoonish, cylindrical tin-can volumes. Still, as implied by the optimistic title The Battery (Limitlessness and Replenishability) (2003), the plane of the table was not exactly new for Hawkins: six years earlier the artist made two sculptural assemblages, each incorporating a cheap folding card table, found images of young male models and food packaging — artifacts of the recent past; ephemeral ‘trash’ that casually reminds one of the historical proximity of the still life to death. In (doomed city) (1997) the table supports a slapdash assemblage of cut-out boys atop a cereal box and a yogurt container. The table is a stage for a provisional tableau that might come undone at any moment should Hawkins return to move the parts around — or perhaps if one were to accidentally bump into the table. city underground (1997) inverts (doomed city) by situating its beautiful vacant boys, disposable cups from 7-Eleven and Taco Bell, a box of Cap’n Crunch and a container of instant noodles as a stalactite-like mass under the table’s surface, literally cloaked in shadow.

In 2003 Hawkins unexpectedly discovered the existence of Creek Indian blood in his lineage, and the ‘identity crisis’ resulted in a series of unsettling paintings that folded the artist’s historical research, along with Native American mythology and stereotypes, into devastated, apocalyptic-looking, allegorical landscapes. If one could see traces of Guston in Hawkins’s tin-can still-life paintings from the previous year, here the ex-Ab-Ex, born-again painter of social narratives now seemed like an explicit model — though one can also detect the influence of Pierre Bonnard’s palette, regional American folk art, and some overtly racist drunken Injun cartoons. Wrath of the Underworld (2004) features a spindly, skeletal figure with a clownish red nose and rosy cheeks, dressed (only) in a patchwork vest and saucepan hat, who is doubled-over and holding a flower while traversing a desolate, pink landscape. Like Plane of Immanence, the perspective is awkward. An outhouse is in the distance and the foreground is sliced away like an archaeological diagram to reveal buried secrets below (sacred?) ground: a massive green bottle, a possum, skulls adorned with feathers, spears, piles of gold coins. Seven years after the table sculptures, the horizontal plane would be reiterated as a crucial threshold between public (‘official’ history, mythology, stereotypes) and private (personal history, identity crisis) in Hawkins’s paintings. For the first time it was clear that the artist himself was occupying that threshold, negotiating the exoticism and alienness of his personal history — not just as a Creek, but as a decadent, ‘slacker’-era collage artist born-again as a painter of abstraction, still life, history and allegory.

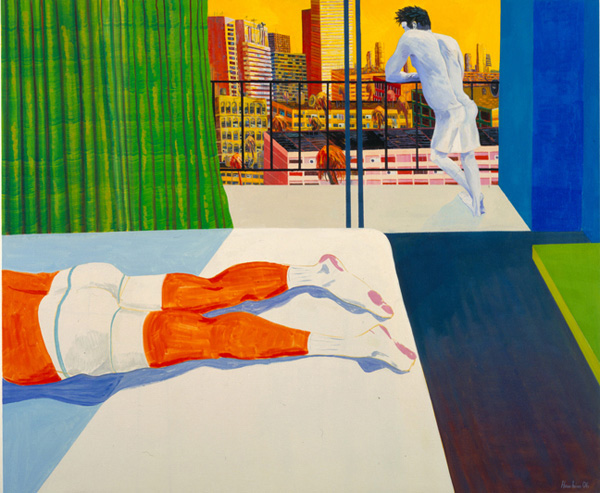

Richard Hawkins, Sunburn (spitting off the balcony), 2006. Oil on linen, 60 x 72 in.

The Indian paintings were followed, rather quickly, by a series of larger genre paintings set in another exotic underground: the Boyquarium, a sex club in Thailand populated by young, sexually ambiguous performers and their older, rather lecherous audience. Here Hawkins collapsed the two sides of his plane of immanence — the stage and the underworld — into one complex, disorienting space where the viewer stands in for the unseen artist as observer of both the observers and observed. Options, not solutions (2004), included in his 2004 show at Richard Telles Fine Art in Los Angeles, is a fitting title for a painting in which three oddball figures — a bulbous, grotesque male tourist in the extreme foreground along the right edge of the canvas; a buff, nude hunk in the distance; and a gawky, chubby boy with a pubescent moustache, manboobs and a bikini-top tan line sitting on the stage at middle left — compete with raucous stripes and checkerboard patterns. Near the orange hunk in the background, a small painting hangs on a wall decorated with garish diagonal lines of olive, mustard, pink and white. Is the painting-within-a-painting a shorthand landscape, or perhaps just an accumulation of horizontal green brushstrokes — not unlike Hawkins’s own ‘abstract’ paintings? Following from the artist’s 1990s collages, these Orientalist paintings are less composed than cropped: Hawkins imposes space on each figure, either crushing them in the frame or dismembering them, so the viewer can lavish attention on constituent parts (Frankenstein monsterish fingers and toes, pot bellies, knobby knees) and their awkward relationship to the whole body. Tan lines demarcate overcooked pink flesh from chalky white skin dressed up with blue and green shadows. Is contestant number 31 in Passing Pageant (2004) shirtless and sunburned, or is s/he wearing a snug wifebeater with nipples painted on the outside? Gender ambiguity becomes the same thing as painterly ambiguity and any remaining divide between abstraction and representation vanishes. Oh, and in case you missed his transformation into the gay Gauguin, Hawkins signed several of these paintings in the bottom corner with rather large, carefully authorial script.

It’s late Spring 2006, and I’m at Greene Naftali gallery in New York. Hawkins has continued with — returned to? — the Thai sex underworld, though it’s clear the paintings have become refined, confident, almost subdued. I’m looking at a large, horizontal canvas titled Sunburn (spitting off the balcony) (2006): a hotel room with another orange hunk — or is it the same orange hunk as before? — lying on the bed, ass up, decapitated by the canvas edge, while a pasty male figure stands on the balcony while spitting on the yellow, sun-drenched urban scene below. I’m seduced by the composed blocks of color: the orange figure, the white bed, the brown floor, the yellow exterior framed by a lime-green curtain on the left and aqua-and-blue hotel wall on the right. A second later I’m also struck by the correctness of the perspective, the unexpected crispness of Hawkins’s lines, including the Newmanesque ‘zips’ of the sliding glass balcony doors, and suddenly I’m suspicious — okay, disappointed — that the artist has used masking tape to make this and several other paintings in the show.

Privately feeling betrayed by the tape, or at least its use by this supposed anti-tape vigilante, I could barely look at the paintings in front of me. I try to get over it, and eventually find my way to the back gallery where I spot a framed untitled collage comprised of two loose ink drawings and a repetitive diagonal composition of … masking tape ‘stained’ by green, red, blue and pink paint. It was a very belated punchline to the joke Hawkins had setup six years earlier in Artforum. And it hit me below the belt. Ouch.