Pasadena’s Collapse and the Simon Takeover: Diary of a Disaster (1975)

by John Coplans

This essay was originally published in Artforum 13, no. 6 (February 1975) and is republished with permission. All original formatting has been preserved. To download a PDF of the article in its original layout, click here.

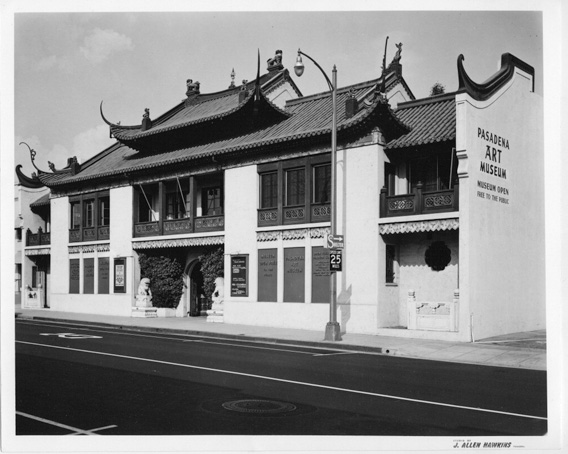

Exterior of the Pasadena Art Museum, located at 46 N. Los Robles Avenue, ca. 1960s. Courtesy of the Archives, Pasadena Museum of History.

Patron: commonly a wretch who supports with insolence, and is paid with flattery.

Samuel Johnson, Dictionary, 1755

The financial collapse of the Pasadena Art Museum, and its subsequent takeover by Norton Simon, an exceedingly rich and powerful Southern California industrialist, raises issues that extend far beyond the problem of the survival of this particular museum. It poses acute questions about the power and accountability of museum trustees, the lack in many American art museums of carefully thought-out policies within their local communities, and the general role a museum should assume within the community of art museums throughout the country.

Problems of control and direction exist for museums throughout the United States, but in museums in the East, they appear to be less severe if only because most of them had an earlier start, better funding, and a larger reservoir of available art objects in both public and private hands. The sheer concentration of resources on the Eastern seaboard – schools of art history, libraries, scholars, experienced museum directors and curators, art magazines and art writers, plentiful collectors, specialist dealers, private galleries, and finally, thousands of artists themselves – far outweighs those in the rest of the country. The pressures of the informed opinion of this art audience play a considerable role in checking excesses. True, such resources exist elsewhere, but they are thinly spread. This means the isolated regional art professional, especially in museum work, has less of these resources to use in struggling against the intense pressures of the wealthy and powerful.

Over the past two decades in Northern California, there has been a veritable fever to build new museums and increase the space of existing ones, often disregarding the fact that there are few existing collections of significance to require such housing. Despite the existence of the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, the M.H. de Young Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Art, and sundry smaller institutions, the past decade has seen the building of two more large complexes at huge cost: the Oakland Art Museum and the University Museum at Berkeley. But apart from the 40 Hans Hofmanns given by the artist to Berkeley, a few isolated post-World War II American works, and the Rodin collection at the Legion of Honor, scarcely any important modern works can be seen in the combined museum collections. Even if all the collections of modern art in the three museums were to be combined with the late 19th- and 20th-century holdings of the legion of Honor, it is doubtful whether one first-rate collection would be formed. Moreover, this skimpy body of work is displayed in an area equivalent to or greater than that of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, and the Guggenheim museums combined.

There are comparable discrepancies in Southern California. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the San Diego Gallery of Fine Art both have undistinguished collections of historical art. Although they attempt to cover 19th- and 20th-century European and post-World War II American art, neither has collections of excellence even in these areas, the major exception being the fine de Sylva Collection at the LACMA, much of which was given in 1946. The point is that the museum holdings are so spotty that they cannot give an overall view either of the achievements of European art since the middle of the 19th century, or even of American art of the past quarter-century, to say nothing of periods such as the Renaissance or Baroque. The Galka Scheyer Bequest, which the Pasadena Art Museum fortuitously obtained in the early ’50s, on the other hand, is a very special resource. Although it basically consists of art formulated in Germany, were it to be united with the LACMA’s School-of-Paris holdings, Southern California would have the beginnings of a first-rate collection of early modern European art under one roof.

As for more recent art, despite a string of exemplary shows by postwar Americans, many of whose works entered local collections, museums are very deficient in this area. One obvious explanation: available museum funds were spent on bricks and mortar.

Problems with museum architecture in California have compounded the dilemma. If the Bay Area has erected two buildings capable of functioning well as museums (Berkeley and Oakland), the same can hardly be said for their southern counterparts. The L.A. County Museum of Art, a finned fantasy with boardroom chichi interiors, designed by William Pereira, and the Pasadena Art Museum, with its ribboned antiseptic caverns, designed by Thornton Ladd and John Kelsey, are as monumentally vacuous in spirit as they are in ideas. The general inhospitality of the buildings to art acted immeasurably to depress the local art audience. So much was promised, so much was planned for the future, so much money was given in good faith, and when the dreams were finally delivered, the sheer obtuseness of the architecture strangled hope at birth.

Ed Ruscha’s painting The L.A. County Museum on Fire might be taken as a symbol of the art community’s bitterdisillusionment and frustration when faced with this fatuous building which betrayed the lack of insight and taste of the LACMA trustees who control so much of the future of art in Southern California. In 1969, the Pasadena Art Museum, with its enlightened focus on modern art, was the one hope left. But such a promise was dashed with the opening of its new building and the realization that this boondoggle was also unworkable.

At a time when one can enter at least half a dozen museums in Germany, Switzerland, and Holland and encounter extraordinary collections of recent American art, when vast sums have been spent in California on bricks and mortar, when museological standards run second to the interests of trustees in one of the wealthiest states in the union, and when an exceptional public museum and collection is handed over entirely to an entrepreneur whom one assumes is a public benefactor, one is forced to ask what happened. What are the social and cultural sources of this situation, and what are the lessons to be learned from this series of disasters?

Ever more dearly today, especially because of recent developments on the American political scene, we understand that our institutions depend upon the character and behavior of those individuals who constitute the leadership. The history of the ambitions, and the decline and fall of the Pasadena Art Museum, reveals many of the problems that have retarded the development of effective museums in California. It is a history of compromises, conflicting goals, egomania, and private greed that has acted against the common good, and has ended finally in a violation of the public trust. This chronicle of pathology reflects more diffuse, hidden, and complex workings in larger institutions. But what has happened to the Pasadena is only an extreme instance of the outcome of predicaments that afflict museums from one end of the country to the other.

The Pasadena Art Museum is 50 years old. It was founded at the height of the largest internal population shift in the history of the United States, when over two million people moved into California. A million and a quarter of these moved into Los Angeles County alone between 1920 and 1930. Still, the city of Pasadena remained an anomalous island within the county. The city was settled during the 1870s by wealthy Eastern families from Chicago, Pittsburgh, and New York as a retreat from the rigors of winter. The palatial, neoclassic, winter “cottage” built by the Wrigleys, of chewing-gum fame, still stands on Orange Grove, a wide, tree lined boulevard. Most of these huge and elegant homes that once lined the street have been torn down and replaced by expensive, banal apartment complexes.

Pasadena is connected to downtown Los Angeles by one of the first freeways built in America in 1941. The tunnels and overpasses are decorated in the ’30s style, and the narrow lanes were designed more for Ford Model Ts than today’s vehicles. In the ’20s, Pasadena had the highest percentage of widows and divorced women of any city in the United States. Seventy-five percent of the taxable wealth was controlled by women. This attracted, according to Carey McWilliams, “scores of playboys, amateur actors, amateur musicians and amateur writers,” He notes, “It is the wealth of Pasadena that has sustained such institutions as the California Institute of Technology, the Pasadena Playhouse and the Huntington Library.”

Apart from its cultural institutions, and the annual Rose Bowl Parade which attracts people from all over Southern California, the city’s only other claim to fame lies in the work of two local architects, the Greene brothers. Influenced by Japanese and Swiss architecture, they built a number of extraordinary houses around the turn of the century. Extremely modern in spirit, with interpenetrating exterior and interior spaces, their buildings are exquisitely detailed with Art Nouveau stained glass and pegged woodwork, offset with huge bouldered fireplaces. In the midst of turn-of-the-century priggishness, the Greene brothers also managed to catch a real whiff of the primeval in their timber frame and boulder houses. One of their finest, the Gamble House of 1908 (a winter home commissioned by the Ohio family of Ivory Soap fame), is sited on the edge of a deep arroyo the Pasadena Indians used as an encampment site, and which abuts the new Pasadena Art Museum.

The museum was first named the Pasadena Art Institute and housed in a wooden building in Carmelita Park, the site of the present museum building. By tapping into the local wealth, the museum’s founders intended to build an ambitious building in the park, but their plans were aborted by the Great Depression. What with the movie, oil, and citrus industries, Southern California did pretty well during those years, but the wealthy Pasadenans from the East who relied upon their stock portfolios were hard hit. As a growing community, Pasadena was dead by 1930. From then on it has slowly decayed, eroding into a self-contained largely retirement community. In time, large numbers of blacks and chicanos moved in, and the city slowly gained a reputation for the worst de facto segregation record in the Western United States. The city administration, ever resentful of outsiders, runs a notoriously bad school system, most whites preferring to educate their children in one of the many private schools within the city.

Some of the old wealth of Pasadena still persists. Shadowy, aged figures float somewhere in the background, cloistered on private estates. Occasionally one might crop up as a major donor of funds, usually earmarked for some special purpose which the museum, with the best will in the world, couldn’t honor for lack of a trained staff or a collection.

In 1942, the museum moved from Carmelita Park to Grace Nicholson’s Chinese house and Oriental emporium. She had given this exotic building to the city upon her death in lieu of taxes unpaid during the Depression. The trustees, at the time, made a pact with the city to retain rights to the Carmelita Park site for about 20 years, providing they raised the funds to build a permanent museum there. Their anxiety to fulfill the terms of this pact eventually led to the ill-conceived and prematurely forced building program of the new museum.

The Nicholson mansion was a solidly built two-story concrete building with a gabled and ornately tiled roof. The building surrounded a beautifully planted Oriental garden. The upper part, originally the living quarters, was used for offices, and what had been storerooms and shops around the courtyard became the galleries. It proved to be an excellent building for a small museum, and for years it rendered yeoman service. Unlike the old Carmelita Park building which was on the old exclusive residential edge of the city, the Nicholson mansion was downtown on Los Robles Boulevard, right in the main shopping center. Pasadena is probably one of the last cities in Southern California where it is comfortable to walk downtown, window gaze, and shop. Small blocks, laid out long before the onset of the automobile, made it easy for people to drop into the museum while shopping, a mode of casual visiting which was impossible once the museum was rebuilt on the Carmelita site.

From the beginning, the museum was a local institution housing, for instance, annual shows of various local artists, and whatever was available in the way of small exhibitions of European art or the art of other cultures largely borrowed from or arranged by other institutions. Nothing very special. Basically staffed and funded by volunteer women’s groups such as the Art Alliance and the San Marino League, it served the community and ran without deficit. (In recent years, the city contributed $19,000 a year to maintain the building. After World War II, the museum opened an education department that pioneered a progressive approach to teaching children art in Southern California, giving many of the minority children in the Pasadena school system their first awareness of art.

In the ’50s, a number of factors changed this situation radically. In 1951, the museum was deeded (and accepted) the Galka Scheyer Blue Four Collection in trusteeship for the people of the State of California on the condition that a catalogue be published within a set number of years. Scheyer, a German child psychologist, came to New York in 1924 to pioneer the exhibition and sale of the work of the Blue Four group — Feininger, Klee, Kandinsky, and Jawlensky. She was friendly with all four artists, who were evidently pleased to let her act as their joint agent, provided, according to Klee, “‘in agreement with Kandinsky, that theirs should not be considered an official association.” Scheyer was not a dealer in the narrow sense of the word, but rather a friendly agent who followed her own profession — teaching art to children — and did the best she could to sell and exhibit her friends’ works, acquiring a large hoard of them for herself in the process.

“Prophetess of the Blue Four,” San Francisco Examiner, November 1, 1925. Pictured: Galka Scheyer, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Alexej Jawlensky.

She gave away her entire collection upon her death. The somewhat ambiguous name “Blue Four” was chosen by Scheyer herself on the basis that: “‘A group of four would be significant though not arrogant, and the color blue was added because of the association with the early group of artists in Munich that founded the ‘Blue Horseman’ … and also because blue is a spiritual color.”

Scheyer moved from New York to San Francisco in 1925, and from there to Los Angeles in 1926 where she lived until her death. The collection she gave to Pasadena consisted of 66 Klees (mixed media), 150 Jawlenskys (mostly oils), five Kandinskys (one oil and four watercolors) and a number of Feiningers. In addition, several other artists were included in the bequest who have little or nothing to do with the Blue Four, notably Picasso, who is represented by a major oil and collage work from 1913. The Klee section of the bequest is probably one of the finest collections of this artist’s work in existence. The Jawlensky collection is unique, consisting as it does of ten extraordinarily fine pre-World War I Expressionist heads, and a full spectrum of each of his Iater phases — the Murnau landscapes, the semigeometric and geometric heads influenced by the Bauhaus, and the late mystical cruciform heads. Included in the bequest to Pasadena was Scheyer’s archive, which included years of friendly correspondence with all these artists. The many Feininger letters in the archive are often illustrated with small watercolors and drawings, recording recent or intended works discussed in the letters. The Scheyer bequest, including many drawings, numbered 600 works all told, and is crucial to the history of German art.

The trustees of the museum must have had some glimmering of the importance of the bequest that had fallen into their hands. It changed the status of Pasadena within the community of museums from a small, unassuming local art center with no significance to the outside world, to one containing an internationally prized asset. Still, for years nothing much changed within the museum itself, largely because there was no professional staff. True, soon after the acquisition of the collection, museum director W. Joseph Fulton traveled selections from the bequest to other museums. But the undated calalogue-cum-checklist of the bequest, apart from biographical information on the artists and a brief note on Scheyer, merely illustrates some of the works.

Fulton was the first of a long series of inexperienced directors. A bright and promising young man with a Ph.D. in art history, he and his wife were brought out to Pasadena from the East. Despite the affability of the board, and what seemed a promising open situation, he discovered after his arrival that there was little or no money available. Fulton tried his best. In 1954 he organized a survey of Abstract Expressionism, and later a show of Man Ray (who was living in Hollywood), and of Siqueros. This exhibition caused severe problems because of the hostile climate to this artist’s politics.

But the board had no sense of what should be done with the museum, and for a professional like Fulton the sense of frustration this engendered must have been severe. A fragile personality, stunned by the adverse circumstances of his situation, Fulton had a nervous breakdown in 1957.

For six months after Fulton’s disappearance from the scene, the museum was without a director until another young historian with a Ph.D. was appointed. Prior to his appointment at Pasadena, Thomas Leavitt had been Assistant Director of the Fogg Art Museum, a university museum devoid of the complexities surrounding a community museum. Leavitt was a patient, low-keyed, and very private personality. He was the last director to remain at the museum for more than two or three years. As we go forward in time, each new director has a shorter and shorter span of tenure. As Leavitt admits, it took him two years to puzzle his way through the network of relationships surrounding the museum and assume leadership.

The museum was entirely dominated by volunteer women’s groups, particularly the Art Alliance, which maintained (and continued to do so for many years thereafter) their own bank account, and would release funds to pay for an exhibition only when it met with their approval. They had direct lines of communication (especially social) to influential members of the board, and continually bypassed the director. In short, the Art Alliance, rather than the board of trustees, was really running the museum. Their power was abetted by the curious circumstance that few, if any, of the 32 trustees ever reached into their own pockets to support the museum.

As he saw it, Leavitt’s first task was to professionalize the museum. It kept poor records (even of what it owned) and lacked even a registrar, let alone a curator or curatorial staff. A difficult and tough situation for an inexperienced director was compounded by the determination of the board to build a new museum on the Carmelita Park site before the option on the land expired, this despite the fact that no real endowment existed to run the small museum as it was. Finances were left to fortuitous largesse, and any annual deficit had to be cleared by begging from the trustees. This situation was an invidious and imperfect way to run a museum, and made hiring a staff, planning expansion of activities, and steering a course free of hazard impossible.

When Leavitt became director, the president of the board of trustees was Eudoria Moore, a local woman of immense energy. Although herself without private wealth, the handsome and formidable Moore and various volunteers were in effective control of the museum; and in the period between Fulton’s departure and Leavitt’s arrival — some six months — Moore had been calling the shots in the day-to-day running of the museum. In addition, she was the principal force behind the projected new building in Carmelita Park.

Plans for this project were well underway by the time Leavitt arrived, and during the course of Moore’s tenure as president, this project, rather than the professionalization of the museum, seems to have been her consuming passion. Leavitt didn’t get any professional help until the sixth year, when he was about to leave. It was in 1962 that Walter Hopps, who had free-lanced a few shows for the museum, was hired as a full-time curator. But still there was no registrar, and Hopps himself was completely self-trained.

Moore conceived of the new museum as “a contemporary expression of all the arts.” She wanted to see it house under one roof various established local organizations: the Pasadena Playhouse, the Pasadena Symphony, and the Coleman Chamber Music Association. This collage of activities, Moore said, would represent “the creative expression of modern man.” Apart from these diverse activities, Moore’s plan included a single administrative office to coordinate publicity, ticket sales, fund-raising, and more.

Although her zeal and rhetorical stance indicated a wide range of interests, Moore was entirely parochial in outlook. She was a dynamic and well-intentioned amateur. Her knowledge of museology scarcely covered Southern California, let alone the rest of the country, and any European models were beyond her ken. She masked rather than supported the chauvinist insularity of Pasadena, but in the end it came to the same thing. Pasadena was a deeply inbred WASP community. Although no board member ever gave any indication of being anti-Semitic, the leadership was completely hostile to members of the mostly Jewish Beverly Hills community, who, with their wealth, sophistication, and emerging collections, could have played an important role early on in the plans to extend the museum. Under Moore’s presidency, Beverly Hills people were denied access to the board, and consequently they gravitated toward the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. When the new LACMA building was built nearer to Beverly Hills, this community, aware of Pasadena’s “neutrality” toward it, naturally fell into its orbit. Only after Moore’s tenure as president of the board did the first Jewish Beverly Hills collector, Donald Factor, join the board, largely at the encouragement of Walter Hopps. Years later, some of the younger Beverly Hills collectors associated themselves with Pasadena. Still apart from Frederick Weisman, who became a board member after becoming disgruntled with LACMA policies, few of these younger people were allowed to participate in the real decision-making. They remained outsiders, juniors who had walked into a weird and complex situation in which they were reluctant to assert themselves. In short, it was their money and not their ideas that was welcomed, and the control of the museum at trustee level was to remain almost exclusively in Pasadenan hands.

As her ally in advancing the new building project, Moore enlisted another trustee, Harold Jurgensen, a self-made millionaire with strong roots among the city bosses, and owner of a chain of fine wine and gourmet stores modeled after Fortnum and Mason in London. Jurgensen, anxious for the social cachet of public service, became head of the museum’s building committee. He had the power, drive, experience, and connections to make the project a reality.

Together, Moore and Jurgensen elicited the interest of another trustee, Wesley Dumm, a remote, mysterious, but extremely wealthy figure who lived like a hermit in the Altadena Hills. Dumm never attended board meetings, and the only evidence of his involvement in the museum was a gigantic star sapphire mounted on velvet and displayed in the hallway near the bookstore. Dumm knew a man connected with Stuart’s Pharmaceutical Company in Pasadena who had hired architect Edward D. Stone in 1957 to design the company’s new pill factory up on Foothill Boulevard. At Dumm’s urging, Stone was hired to design the new museum complex, and the board hoped for a large donation from the pill factory owner to swell the building fund. Wesley Dumm himself paid for feasibility studies and other preliminary costs, and promised to make a half-million-dollar donation to the building fund. Angered later at the direction the museum took, Dumm never honored his pledge.

A preliminary design from Stone included a theater, concert hall, and various other performance areas, as well as exhibition galleries. Conceived in an Egyptian revival style, Stone’s building was huge, and far beyond the resources of Pasadena either to build or maintain. The initial proposal was eventually revised and cut down in size. By the time Leavitt left the museum, funds had been raised from different donors amounting to somewhere between $1.5 and $2 million. The lack of an endowment fund to maintain the museum was constantly and conveniently fudged over. Monies were held in so many different funds that what was endowment for maintenance and what was purely for the proposed building became a matter for conjecture – a question of who juggled what to get the answer that was required at any given moment. For example, a Mrs. Crosset gave $750,000 to the endowment fund, which was subsequently used with her consent as a guarantee on the building loan. The board called the Crosset endowment “unattached securities,” which clearly they were not. In addition, at the very height of the stock market boom Mrs. Crosset’s $750,000 was so poorly invested that within a year or two its value tumbled to around $300,000.

After six years without a professional staff, with a substantial collection on his hands and the most inadequate of records, a tiny operational budget, and no fixed endowment, Leavitt was worried at the way things were going. He felt that the museum was on a “doomed course.” He hadn’t the basic concurrence from the board that a dollar for the building should be matched by a dollar for the endowment before the project could go ahead. Instead, he had Mrs. Moore’s incredible enthusiasm. Leavitt felt that the level of community support had yet to be correctly assessed, and that reasoned planning had become wishful thinking. He approached individual board members to sound them out on his anxieties, but got the brush-off. Leavitt couldn’t see that the means were available to jump from a small museum with an annual budget well under $100,000 to a major institution which would require several hundred thousand to keep its doors open. He began to negotiate quietly for another job, which he found — director of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, a general museum in a small and very wealthy community a couple of hundred miles north. The last important show Leavitt organized at Pasadena was a Robert Motherwell retrospective, and, to a surprised annual general meeting held in May of 1962, Leavitt announced his resignation.

It was at the 1962 annual general meeting that Mrs. Moore, too, stepped down as president of the board, and Harold Jurgensen was elected. Although she resigned as president, Moore retained her position as a trustee. At the same time, she extended the range of her activities in the museum by opening a design department to which she appointed herself curator. In doing so, Moore founded a separate corporation within the museum called California Design.

She campaigned vigorously and most successfully for state and private funds, mostly from industry, over which she retained full control. Perhaps if the same amount of energy had been directed into raising funds for the museum itself, a quite different picture would have emerged. The straightforward purpose of California Design — to promote knowledge of design in the state — allowed Moore to give full reign to her populist instincts. She began organizing what became an annual exhibition. This included a large and expensive colorplate catalogue and a specially designed installation which took up the whole of the Nicholson building (and later, the new museum) for several weeks. In essence, the show is a juried annual of handicrafts — pots, weaving, art furniture, bits of industrial design, and commercial and household knicknacks. The exhibition was tasteless, immensely popular, and brought considerable gate receipts. It also successfully alienated every designer and architect of note in California.

Most disturbing of all was the introduction of a former president of the board and a trustee into the museum’s structure as a working professional. Though Moore headed California Design, she nevertheless saw herself as the curator of design, and she demanded that she supervise anything related to design and architecture. Beyond this, she cast a jaundiced eye upon the everyday activities of those professionals who were within the museum. What was at variance with her own firmly held opinions was immediately carried either to the director, the other trustees, or straight into the boardroom. After all, she could demonstrate that her program made money and had a huge attendance, two ingredients that every board member understood. This impossible situation was aggravated by Moore’s incapacity to distinguish the meaningful in art from the insignificant; since everything was equally significant, everything deserved a place in the museum.

When Leavitt left the museum, Walter Hopps was appointed acting director. Hopps, a third-generation Californian, is one of those people who fits into the contemporary art world with such natural ease that it would appear to have been created especially to use his talents rather than the other way around. As a schoolboy he had hung around the Arensbergs, and he knew their remarkable collection intimately before it had left for Philadelphia. At Stanford and UCLA he studied biochemistry, but chucked it to immerse himself in the California art scene and later married an art historian. His earliest activities centered as much around San Francisco as Los Angeles. Between 1953-56 he began to organize exhibitions in Los Angeles wherever he could find the space. In 1957-58 he started The Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles with Edward Kienholz, which, in fact, was more an artists’ cooperative than a commercial gallery. When Irving Blum became a partner in the gallery in 1959, Hopps began to work more at Pasadena as a free-lance curator, and by 1962 he had become a full-time curator there.

Hopps knew artists’ studios in both Northern and Southern California, and he understood the interrelationships between the two scenes. The museums at the time were doing little to support the work of younger artists. The San Francisco museum had atrophied under the dead hand of George Culler. The Los Angeles County Museum of Art didn’t yet exist — art was still mixed up with natural history at the old county museum. In 1962, Artforum started up in San Francisco, and by 1965, when the magazine moved to Los Angeles, it had already proved to be a natural vehicle for giving the West Coast (as it came to be called, instead of Northern and Southern California) some confidence about its own affairs. The time was ripe for a knowledgeable and energetic museum man who could steer a small contemporary museum in the right direction, and, with Leavitt’s exit, Pasadena seemed to offer Hopps the chance.

Immediately after the May, 1962, annual meeting at Pasadena, newly ejected board president Harold Jurgensen took Hopps aside to define their relationship: “You don’t know anything about business, and I do, so don’t you ever argue with me on that score. I don’t know anything about art — I don’t know the difference between a Ming bowl and a Bangkok whorehouse — so I’m not going to argue with you about art. Understood?” Busy as he was, Jurgensen was in and out of the museum, going over every aspect of its operations as if it were one of his stores, even down to checking to see that the toilets were clean and stocked with soap and paper towels, Jurgensen didn’t bother with the social rituals Pasadena so loves; his meetings with Hopps were sharp and to the point.

Leavitt had briefed Hopps on the problems with Stone’s proposed building.When Hopps raised the matter with Jurgensen, he found that the board president couldn’t care less whether or not the architecture was good or not. Only one thing interested him — its cost. Though the building had never been put out to bid, he figured the cost on a square-foot basis, and decided that it would be outrageous. Without consulting the full board, Jurgensen ordered Hopps to dismiss Stone. The decision was good for action, but bad as policy; the other trustees didn’t know what was going on, and many were severely alienated — most particularly, Dumm.

Hopps proposed to the board that the Nicholson mansion that housed the museum be extended north into the parking lot. The plan provided for access to a loading dock, and left parking for the public. Hopps also suggested that the museum should acquire the two run down brick hotels that abutted the museum on the west. These could be converted into spacious gallery and storage space. Plans, in fact, were drawn up for this project, and there was money aplenty in the kitty to finance this extension and leave a substantial endowment.

Yet Mrs. Moore, among others, couldn’t bear the idea that the museum should lose its option to build in Carmelita Park. Trustee Robert Rowan led a faction that declared Hopps’s proposal was too tacky, and that it would not attract monied people from Beverly Hills. Rowan was one of those trustees who felt these people needed to be brought into the orbit of the museum as collectors and supporters, despite his personal dislike for the brash nouveaux riches of the movie industry.

Hopps counterproposed that if indeed a new museum must be built on the site in Carmelita Park, then the architect should be a Southern Californian, someone with whom the museum could work closely. He suggested that a competition be held for the design of the museum, and Jurgensen directed him to draw up a list of names for the board. Hopps nominated Richard Neutra, John Lautner (a protege of Frank Lloyd Wright), Craig Ellwood, Thornton Ladd, and Charles Eames. Hopps felt that a lightweight industrial structure (such as Eames was skilled in designing) might save the landscape naturalist John Muir had designed for Carmelita Park, and some money for the endowment.

During the next few months, Jurgensen evaded his director. When Hopps asked him what was happening with the competition, the board president put him off. Finally Hopps demanded an explanation. According to Hopps, Jurgensen said, “Your list of names was good. The committee has considered everyone, and Thornton Ladd has won the competition.”

“How?” Hopps asked. What competition? he thought.

“Ladd’s mother is a very wealthy woman,” Jurgensen replied. “She lives here in Pasadena, and I’ve talked to her. We have a little understanding, She will give the museum a personal donation of at least double Ladd’s fee. We can’t turn that down. I assume that all five men on your list are equally good, so we’re not going to turn down the one that we can get for free…From time to time I’m gonna tell you that something is just the way it is. And this is one of them. Ladd will be the architect.”

At first Hopps felt betrayed. But, since Jurgensen had backed him to such an extent in his attempts to put together a professional staff, and in his proposed exhibitions program, Hopps began to feel that the building the museum would get from Ladd and his partner John Kelsey could be negotiated. Hopps had hired Gretchen Taylor, a research librarian and art-history student at UCLA as registrar, and a preparator, Hal Glicksman. In 1965 Hopps hired Jim Demetrion as curator (Demetrion had already guest-curated the museum’s Jawlensky exhibition). Now, Hopps thought, things were beginning to make some sense. He had planned a series of scholarly exhibitions around the Blue Four collection, as well as a series of shows of particular interest to him: a Duchamp retrospective, exhibitions of Schwitters, Johns, Cornell, and some Californians, John McLaughlin, Hassel Smith, and Frank Lobdell, among others.

The national economy was booming, and there seemed to be plenty of money around. Collections could be built. Hopps himself was closely advising collectors such as Gifford Phillips, Betty Asher, Ed Janss, Frederick Weisman, Monte Factor, Donald Factor, and Betty Freeman. Perhaps California might at last have a first-rate modern museum. Hopps’s last exhibition as Pasadena’s curator, ” The New Painting of Common Objects,” the first American museum show of Pop art, had attracted national attention, partly through extensive coverage in Artforum. (I had written on the exhibition myself after I arrived in Los Angeles from San Francisco in 1963. lt was then that I first closely followed the Pasadena Art Museum’s programs and problems.) The exhibition set a major goal in Hopps’s programming, a goal which paralleled the ambitions of the young magazine, that is, to advance the West Coast as an originator of artistic culture vying with that being made in New York. Issuing from that year, also, was the major coup scored by the museum in the international art world, Hopps’s retrospective of Marcel Duchamp.

In setting up Ladd and Kelsey as the “appointed architects” for the new museum, Jurgensen promised Hopps that the design would fulfill all of his requirements. Jurgensen was so convincing, said Hopps, “Everyone figured, ‘Oh, to hell with it, we’re all going to have a hand in it, so it can’t be that bad. It’s a beautiful park anyway. Maybe it will work out for the best after all.'” Meanwhile, galleries in the old building were ripped apart and refurbished, and the planned exhibitions program began to absorb the staff’s energies. Hopps made contact with Ladd and Kelsey, to sound out their thoughts, discern their general theoretical approach, and to find out if there were immediate problems to be discussed. But neither architect wanted to discuss theories. “We had lunch, we gossiped and chattered, but no talk on the new museum. Ladd talked about a glider he flew. It was weird; they were completely evasive.” Hopps saw them frequently over the next year or two, but without learning any concrete proposals about the form the museum might take. Finally, pressed by Hopps, Ladd promised, “I’ll show you our design first, and then we’ll really talk about it. You see, we’re working in three dimensions, so we can’t even show you a sketch.”

Some three years after their appointment and (unbeknownst to him) very near the end of Hopps’s tenure at Pasadena, Ladd phoned to say he’d got a surprise, and invited Hopps over to the firm’s offices. In a loft above the offices Ladd and Kelsey had built a large model of the new museum from bent kraft paper. The museum was designed in the shape of an H with circular galleries at the end of each arm. Combined with the auditorium, the museum complex resembled a flayed skin spread over the ground. This design apparently evolved from the interpenetrating rhythms of the bent paper, and the ground plan was superimposed — function followed form. Jurgensen and board president Robert Rowan were beaming over the model when Hopps arrived. “They were so excited that they were practically toasting each

other and the architects in champagne. The building was grotesque,” says Hopps, “and I was unable to get a word in edgewise to stem the tide of praise.”

The site had been flattened and destroyed. And, since the architects had noted that sculpture in a rectilinear gallery often had to be viewed against the angles formed by the corners, Ladd and Kelsey had rounded every corner in the galleries and halls. All the

walls, except in the extensive corridors linking the pavilionlike galleries, were curved. Lenslike domes were to flood the floors — not the walls — with pools of light which would shift with the sun. The lighting system, concealed within finned recesses of busy ceiling detail, harshly illuminated the walls. The galleries couldn’t be shut 0ff for installations, and for the most part, the focal point from one axis to another revealed not walls, but windows opening onto Pasadena. Several of the galleries ended in small U-shaped chambers like apses, completely unsuited to the display of works of art. What was left of Carmelita Park — that is, the grounds for the display of sculpture — was taken up by a long reflecting pool, and a huge asphalt parking lot behind and at the side of the museum. The design segregated the museum from its grounds to such an extent that (unlike a courtyard situation) it was impossible to achieve a continuity between large works displayed outside, and more fragile works inside the museum.

It was clear from the plans that security at the museum would become an immense problem. Instead of the two or three guards used at various times in the Nicholson building, a veritable platoon would be required for the new museum. Since access to the grounds was unrestricted, it would be impossible to guard sculpture outdoors. The auditorium could only be entered by walking the entire length of the museum, which meant that the galleries had to remain open whenever events took place in the auditorium at night. The fire code required that the four exits nearest the public toilets in the auditorium be left open for emergency use. This meant that a guard had always to be stationed at the entrance to the auditorium whether it was in use or not. A door in the lower level graphics gallery opened onto the offices and the main storage area of the museum. Since there was but one staircase down to that gallery, this door abutting the main vault had to be left open as a fire exit, and yet another guard had to be permanently stationed there.

(On one of my own inspection tours of the building during its construction, I noticed that an overhang above the main loading dock was built so low that a semi-trailer or other tall truck could not back up to unload. The architects refused to alter the design lines of the building to accommodate a truck. Consequently, whenever it rained, no works of art could be brought in or out of the museum!)

It was a disastrous, crackpot design. Instead of a flexible building suitable for displaying a wide variety of art, the architects had designed a sleek decorator’s dream, full of awkward restrictions. When Hopps saw the plan, he felt “totally fucked and betrayed. In my fantasies, the only thing I could have done to express my true feelings would have been to make noises like a character from an Ionesco play, and thrown myself bodily into the middle of the model, crushing and wrecking it. And just as I was about to spout out my shock, and say ‘No, it won’t work, it’s all wrong,’ Thornton Ladd had me by the arm in a comforting way, saying, ‘Don’t

worry. We can change anything. Don’t worry. This is merely a presentation. lt’s a beginning, a temporary.’ And I’d say, ‘Well, look. What about those corridors?’ to which he replied, ‘We don’t have to have those corridors.'”

Ladd and Kelsey, Hopps said, “had a polished verbal technique where they would present some terribly accomplished fact, and then smooth things away by saying, ‘Things don’t have to be that way…Don’t worry, everything will be all right. That doesn’t have to be that way.’”

“But you’ve destroyed the site,” Hopps complained.”

Oh, no,” Kelsey or Ladd would reply, “We can do anything with the site.”

“But the model shows you’ve leveled the site,” Hopps said.

“Oh, well, that’s just for the presentation,” they replied in unison.

The wasteful design of the new building finally was to prove a mortal blow to the independent survival of the museum. The cost of extra personnel to guard the rambling space, as well as the power to heat and air condition the building was to add a huge sum per annum in excess of what a more tautly designed building would have cost for these same items. Moreover, Ladd and Kelsey had purposely designed it so that it would be impossible to build the museum in stages, adding wings or galleries as funds allowed. II was an all or nothing job which, once built, would be extremely difficult to add to or change.

Some minor amendments were made in the design at Hopps’s insistence. He told the architects point-blank that he would seal off the light domes above the galleries once the building was completed. So Ladd and Kelsey, instead of revising the design, kept the domes as external decorative features, sealing them and planning an internal lighting system with metal fins to conceal the fixtures. Also, the planned entrance on Colorado Boulevard was shifted nearer to the car park, and more toward the middle of the museum. A section of the grounds was fenced for sculpture. But apart from several minor details, Ladd and Kelsey were unyielding in their determination to force their design concept through regardless of consequences. And, with Jurgensen’s special fee arrangement, and Rowan’s uninformed but evident pleasure at the design, there were no forces on the board strong enough to say them nay.

Even those who saw the folly of the design could not bring themselves to urge a cancellation. One architect had already been fired at great expense. Ladd and Kelsey had worked so long without consultation that getting rid of them would involve another huge fee. Moreover these board members felt that such a move would damage the morale of the small community of support, and hurt the museum financially.

The destruction of Carmelita Park was a tragedy. Scottish emigré John Muir, naturalist, friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Theodore Roosevelt, and founder of the conservationist Sierra Club, had planned the park. Muir was instrumental in the preservation of wilderness areas throughout the American West (Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Petrified Forest). Yet Carmelita Park was the only public park he himself laid out and planted.

Although they were fully aware of the significance of the site, the architects planned a building that completely obliterated it. It was yet another manifestation of that pathological frontier mentality that lives on in the Southern California psyche. To such a mind, everything is expendable. Whatever remains from the past can be torn down to make a new start, so that finally everything is disposable as waste. While the Dodge House by Irving Gill and the Richfield Building are bulldozed, the ersatz dream of Disneyland is built not far away. Muir’s park is savaged by a die-stamp design which Ladd and Kelsey repeated not long after for a department store. Unlike the Eastern United States, there is no desire to forge thoughtful links between past and present in important public projects in California; things only seem to last by reason of inertia — because no one can as yet make a profit by destroying them.

Muir rendered homage to the gentler spirit of man by laying out his park on an old campsite of the Pasadena Indians, a tribe brutalized out of existence by the missionaries and early settlers. Ladd and Kelsey had a few of the trees dug up and boxed for replanting, but they died.

In 1963, Jurgensen stepped down as chairman of the board to devote more time to his business. But he resumed the chairmanship of the building committee, and at the same time managed the museum’s funds. The board also appointed a full-time business manager. This wise move might have saved the building program. The appointment, however, went not to a sharp young man or woman who would have welcomed the job as a step in an ongoing career, but to one of the boys, Donald McMillan, a retired Pasadena city manager on full pension. McMillan, who was in his late sixties, was also chairman of the Southern California Rapid Transit District board at $30,000 per annum. He appeared in his office at the museum a few mornings a week to sign checks. He was not responsible to the director, but through Jurgensen to the board. He was salaried at a higher rate than the museum’s director, so that over several years, around $100,000 was paid to an aging and ineffective man already earning a substantial salary from two other sources.

Whatever might be said in criticism of him, Jurgensen was a man of his word, warm, human, approachable, and if at times far from correct in his decisions, at least decisive. He never interfered in esthetic decisions made by the museum staff. Robert Rowan, a trustee collector, who replaced Jurgensen as president of the board, was, on the other hand, one of the most equivocating people it has been my misfortune to come across. He was, I would guess, in his middle fifties when he became president. Well-educated (Eton and Cambridge), and married to a charming younger woman far wealthier than he, Rowan is affable, courtly, and a good host, albeit somewhat distant in the English manner. His father’s aggressive speculation in Southern California land provided the family fortune. But neither Rowan’s birth nor his stylish English education had provided him with business skills, and in his hands the family business that he and his brothers had inherited declined. His father’s primary investment was in downtown Los Angeles, which, like many other urban centers, went through a period of extreme decline. During the years after his father’s death, Taylor Caldwell Company moved in to replace R.A. Rowan and Company as the major real estate firm in the downtown area.

Like many of his generation who had inherited their wealth, Rowan was haunted by the specter of the Depression, of being poor. His whole attitude toward money is defensive; he cannot bear the strain of parting with it. As he began to shoulder the financial burden of the museum’s deficit, small as it was in the early years, he became less affable. Always nervous, he became more irritable and erratic. A constant worrier, he was uncomfortable at meetings of the museum’s executive committee and the board. He preferred to meet more informally, usually at the Annandale Golf Club, or at his own house. There were lengthy strange meetings, usually over lunch or around social affairs, at which nothing was really decided. Hating arguments, fearing any bad publicity, he either put off decisions or made them privately.

Tragically, the trustees and the interested local community believed that the future success of the museum depended entirely on Rowan, that his wealth and participation were crucial to its success. The other board members were by and large local people of no particular cultural sophistication who looked to Rowan for guidance. He had social cachet, and he collected. In most communities, it is the people of Rowan’s class who make so many cultural decisions because they have the backgrounds that provide the contacts that attract the money so that everything can fall into place. Despite their reservations about his leadership capacities, the Pasadena trustees came to feel that Rowan was necessary to link everything up.

For Rowan, because he was directly financing the deficit, the museum became a private preserve akin to his own household where he could order things according to the standards of his own taste. His only problem was the staff. Although a nuisance, they could always be replaced. During the period of Rowan’s tenure as board chairman, 1964-70, there were four directors and such a rapid turnover of staff that the only person capable of grasping what had happened and why was the president of the board. Behind all of Rowan’s decisions lurked the assumption that an endless reservoir of better people existed who would gladly come to Pasadena.

Rowan rarely disagreed outright with any member of the staff, especially in a meeting. Rather he would wait until the next meeting or chance occasion brought him face to face with the person with whom he had taken issue. According to the directors of the ’60s, he would announce that he had checked on the matter with other more senior and experienced professionals at other museums, that their advice was contrary to that of the staff, and that he would be inclined to follow it. He developed this indirect decision-making formula to the point that directors and board members never quite knew who was making the decisions, Rowan, some other museum official in absentia, or themselves. Since Rowan had an endless number of “consultants” up his sleeve, any matter which was at one moment agreed upon might later be called up for question.

Rowan, like many of his trustee colleagues in other museums, persistently restricted the decision-making processes to as small a group as possible and one dominated by himself. In this, he was abetted by the usual truancy of most board members when meetings were held. Consequently most of them hadn’t the faintest idea as to what was going on. Since they had only a vague notion of what a trustee’s duties at a museum consisted of in the first place, from the point of view of both museology and public accountability, the trustees at Pasadena basically served to rubber-stamp Rowan’s decisions, at least between the years 1964 and 1970. The president, therefore, was able to promote an image of himself as a decisive leader. He could assert that the growing importance of the museum was the result of his leadership, not the efforts of the staff, an indulgence he would never have allowed himself in the world of business affairs.

And the museum was indeed becoming important. The greater Los Angeles area, unlike other regional cities, is an important art center with a vast network of varied educational institutions and a large population of artists. Pasadena was their principle resource for the firsthand viewing of modern and contemporary art which they would not otherwise see except through slides, and magazine and book illustrations. It was this audience, not simply the small community of Pasadena, that the museum was addressing.

Few trustees understand that museum directors and curators, since they function in the open, are directly accountable in a way that trustees are not. Exhibitions will be examined in the press, both local and national, lay and professional. Directors and curators are subject, too, to the judgments of their peers in a jealous and begrudging profession, and their efforts are scrutinized as well by art historians, artists, dealers, and the others who make up an informed art community.

Should a curator pioneer or cater — or do a Iittle of both? To what extent should a regional museum devote its program to local artists, to nationally known ones, or to historical or didactic exhibitions of its root culture? What is the importance of each exhibition within the program as a whole? Considering a museum’s overall resources — budget, space, staff — what exhibitions should be purchased, and which originated?

Once the trustees have laid out the general concerns of the museum, to what extent and in what direction should the collection be extended? And with which specific works? To what extent should the staff advise trustees what to collect? Is the collecting activity speculative, or might it eventually bring works into the museum? Is it ethical that trustees’ works be shown in the museum’s exhibitions, and illustrated in its catalogues — since this will doubtless enhance the works’ market value?

There is, then, a nexus of questions that museum trustees are not obliged to deal with but which directly concern the staff. The constant tug-of-war between Rowan and the senior staff, a process of proposal, counterproposal and compromise, ill served the dynamics of the Pasadena’s situation. Typical was Hopps’s experience in 1965. Before he was to leave for Brazil to organize the American section at the São Paulo Bienal, Hopps had booked a traveling exhibition of Larry Rivers paintings, organized by Sam Hunter, to fill the museum during the summer. Hopps and his curator Jim Demetrion were installing the paintings when Rowan strolled into the museum to watch them at work. Said Hopps, “Rowan was looking around, enjoying the paintings and laughing. Suddenly he was looking at Rivers’full length portrait of Napoleon, and his mood changed, his attitude became chilly. Something was wrong. He took me aside and said, ‘Walter, that painting has to leave the show.’

“I said, ‘You mean Napoleon?’

“‘Napoleon, Napoleon,’ he replied. ‘That painting!’

“‘Why?’ I asked.

“He took me over to the painting and said quietly, ‘It’s called The World’s Second Greatest Homosexual.’ I though he was joking, and I laughed. But he was serious. ‘We can’t have homosexual paintings in this museum. There must be others!’ He looked around in fear and worry, and repeated, ‘Everything with this homosexuality has to come out of the show.’ He went over to a full length painting of Frank O’Hara standing naked in a pair of big shoes and said, ‘This one too.’ I knew I was leaving soon, and that Demetrion would have to be in on this matter, so I called him over and told him what Rowan had said. Demetrion thought Rowan was kidding, but then, sensing the anxiety in the air, he realized Rowan was serious, and he came on tough.”

“He said, ‘Bob, you can’t order the removal of these paintings. We’d be a laughing stock.’

“Rowan replied, ‘You boys had better think this over. I’ll be back this afternoon for your reply.”’ At which point he left.

Hopps and Demetrion stuck to their guns about the paintings, but they had to compromise. The paintings were exhibited without titles, and identified only by catalogue numbers.

Rowan was also easily influenced by other board members in matters of decorum. Barnett Newman, pleased by the way Hopps and the museum had handled his presentation with a group of younger artists’ work at São Paulo, offered to travel his upcoming exhibition at the New York Guggenheim Museum to Pasadena. Rowan suggested that the 14 abstract paintings linked thematically by the title Stations of the Cross might offend the local clergy. Other board members agreed, and the exhibition was canceled.

Like many other regional collectors, Rowan bought according to the signals of Clement Greenberg. He bought Louis and Hofmann in depth, and Olitski by the square yard. Rowan owns the largest collection of Olitski’s work in private hands, as well as many other Greenberg-certified artists. At the same time, Rowan obtained remarkable examples of early work by Lichtenstein, Warhol, and Rosenquist from Leo Castelli, practically all of which he later sold for a handsome profit. By “handsome” I mean roughly ten times what he had paid.

At first Rowan gave $15,000 or so a year to help make up the annual budget deficit of the museum, and later this tax deductible amount grew to around $50,000 annually. But in his profit from the sale of Roy Lichtenstein’s Temple of Apollo, for example, a painting he bought for $6,000 in 1964, and sold this year for $250,000, Rowan more than recouped the money he gave to the museum. He sold many other paintings in this manner, starting in the mid-’60s when he sold an early Frank Stella he had purchased for $1,500 to the San Francisco Museum of Art for $15,000. At the time, Pasadena owned nothing by Stella. But there is more to this incident. One day visiting the museum, I chanced to meet Rowan chatting to Demetrion in the courtyard. He asked Demetrion and me to look at two Stellas of the same size, date, and series. He said he had decided to sell one, and asked us to judge which was the better one he should keep. Since a promise was implied in his request that the better of the two paintings was being kept for Pasadena, we were eager to comply. Demetrion and I made a judgment that coincided, and Rowan concurred.

Only then did it become clear to me that the rejected painting was being sold to the San Francisco Museum of Art. And, though it was transported there directly, I overheard Rowan instructing his secretary to make sure that the Andre Emmerich Gallery in New York invoice the museum for the Stella, and use the $15,000 paid by the museum to buy a Louis painting. Rowan, then, bought the two nearly identical Stella paintings for speculative purposes. The sale of one recouped the cost of both, and gave him a handsome profit. The Stella he retained would now bring around $60,000. The Louis he bought for $15,000 in 1966 is worth around $125,000. So, for an original Stella investment of $3,000, he gained $137,000 in a period of ten years. It was invoiced through Emmerich as if it were simply an exchange of one painting (the Stella) for another (the Louis).

In spring of 1966, the plan and model for the new building was to be presented by the director and the president of the board of trustees at the museum’s annual general meeting. Hopps, exhausted, in the midst of a split with his wife, felt unable to face the membership and explain why the plan was a disaster. He had flown from New York for the meeting, but when he arrived at the L.A. International Airport, he wandered aimlessly, suitcase in hand. He felt himself about to have a nervous breakdown from the accumulated pressures and the difficulty of his relationship with Rowan. Phoning a psychiatrist friend, he had himself admitted to a hospital, and rested up for a couple of weeks. The new building was enthusiastically received at the meeting. Not long afterwards, Rowan told Hopps he doubted his capacity to handle the directorship, and fired the man who had virtually single-handedly lifted the little museum into international prominence.

Upon Hopps’s departure in 1967, Demetrion, whose total museum experience amounted to the two and a half years he had been curator, became acting director. Demetrion, however, is a straightforward man who correctly assessed that the problems at Pasadena were beyond his competence. He rapidly discovered that Rowan and Jurgensen, and not the board of trustees, were running the museum. He didn’t know until later that the director had no fiscal responsibility for the museum, but that the business manager reported via the treasurer to the board. In any event, Demetrion accepted the directorship on four conditions: 1) that his salary be a dollar a year more than that of the business manager; 2) that an outside expert be brought in to go over the plans for the new museum, and his recommendations accepted by the board; 3) that a sum of not less than $25,000 per annum should be made available for acquisitions; and 4) that the director should have the right to appoint his own staff. These terms were agreed to.

But, while he was in Chicago borrowing some Joseph Cornells for the exhibition of this artist’s work that Hopps had planned, the cab Demetrion was riding in overshot the turnoff, backed up, and was rammed by a following car. Although himself injured, Demetrion rescued the Cornells before the cab caught fire. During the time he was in the hospital, the plans to retain an outside consultant were delayed. After much stalling, David Vance, who worked as associate registrar at MOMA, was brought in as consultant. In his report, Vance castigated the museum because “security was a sieve.” He made many other recommendations of which only a few were incorporated. Nothing relating to the esthetics of the building could be altered, of course, but Demetrion pushed hard for the widening of the corridors. It was only after Leo Castelli saw the plans and told Rowan that “they were ridiculous” that Rowan finally convinced the architects to make some alterations. Still, though both Demetrion and Vance knew that the lighting system was inadequate and unsuitable, nothing said would convince the architects or Rowan.

Since the museum already had serious problems meeting its annual deficit, the trustees met Demetrion’s demand for a $25,000 acquisitions fund by forming the Fellows of Pasadena Art Museum. This group of younger people donated an annual sum in return for which they became involved in the affairs of the museum and attended evening classes on the history of modern art. With these funds, Demetrion was able to buy over the next two years a Cornell box, a Kelly painting, an Oldenburg sculpture, and works by several West Coast artists, including Robert Irwin and Larry Bell. These were the first works of any significance to enter the museum’s collection since the acquisition of the Blue Four collection.

Demetrion insisted on appointing his own staff since Rowan wanted to name Alan Solomon, former director of the Jewish Museum, as curator in absentia. It is interesting that Solomon was among the growing number of directorial emigrés from trustee intrusions. Rowan’s idea was that Solomon would continue to live in New York and curate exhibitions for the Pasadena from there. Demetrion refused. I was then director of the art gallery at the University of California at Irvine, and had just guest-curated a Lichtenstein retrospective for the Pasadena in 1967. Demetrion invited me to become the new curator (although he didn’t tell me of Rowan’s attempt to hire Solomon), and I accepted. My first work as curator al the museum was an exhibition of Cezanne watercolors.

Demetrion tried hard to bring order to the affairs of the museum. He met regularly with the seven volunteer groups, trying to get them together in one meeting at a time, which proved impractical. He kept pushing for the resolution of the problems with the Oriental wing in the new museum. Ground had been broken, and the building was proceeding apace, yet no Oriental curator had been appointed, nor could Demetrion obtain the funds to pay one. Still, Rowan and Jurgensen constantly promised Mrs. Steele, a major donor, that an Oriental wing would be included. Finally Demetrion realized that the problems of funding and staffing the new building would be so insurmountable that in early 1969 he decided to quit. He looked for another directorship and soon found one at the Des Moines Art Center. After having held the directorship for barely two years, Demetrion announced that his resignation would take effect prior to the opening of the new building.

The following history takes the Pasadena Museum on to further stages of inevitable deterioration and imminent defeat. As a director’s appointee, without mandate from the board, I offered an undated resignation to Rowan. Circumstances would have inspired anyone in my position with an extreme reluctance to lobby for the thankless directorship. But it was agreed that I would be a caretaker officer, seeing the museum through the critical period of its new opening and programs.

The immediate interim should be characterized, mildly, as a panic. Lacking visible access to the executive committee, and faced by the departure of the professional staff with that of the outgoing director, I devoted myself to making the new plant a working museum, with a guaranteed schedule of events. A strike at the building site jeopardized all construction deadlines at about the moment that I discovered the lighting system, once we were finally able to test it, bore no relation to the needs of lighting works of art. At the same time as I had to redesign the lighting system, it was also necessary to campaign for new gifts for the museum, so that the 80,000 square feet at Carmelita Park would not ludicrously dwarf our present slim holdings. (There was an under-the-wire urgency about this campaign because we were in the last year that artists could give works of art to a museum and deduct them from their taxes.) As for upcoming shows, we booked an exhibition of Oriental art from the Brundage Collection, to be followed by the Bauhaus exhibition from Germany. The “grand” opening was to be celebrated by a survey of postwar American art, East Coast and West, guest curated by Alan Solomon, now settled at the University of California, Irvine. Such, then, were projects that came variously undone through the predictable confusion of mismatched interests, grudging and negligent patronage.

In order to earn money for purchase of works of art, I proposed that the museum review and deaccession a number of middling 19th-century paintings in the basement, of market value, though of no museum quality. But the funds realized were used for general expenses, and never for this purpose. Then, too, nothing could have better sabotaged gifts from the trustees than the rumor that Rowan was about to bestow his collection upon the museum in time for the opening. But if collectors shied away from the thought of competing with his vast assets, the Noland and the Schlemmer contributed by his family would have allayed their fears. Nevertheless, on a trip to New York in that year, 1969, I secured fine gifts from or of Kelly, Lichtenstein, Albers, Andre, Rauschenberg, Judd, Serra, Nevelson, Warhol, and Morris. In Los Angeles, Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, Ron Davis and several colleagues also gave generously. With a Frankenthaler and Flavin donated by trustees, and a dealers benefaction of an Agnes Martin, the museum suddenly had enough works to rotate around the American wing, and the beginnings of a good contemporary collection for the first time in its history.

At this time, shortly before Demetrion was to leave, two events occurred. The first was that Tom Terbell, a young banker and vice-chairman of the board, took a leave of absence from his job in order to serve as acting director. The second, far less amiable, surfaced when the museum learned that Solomon interpreted his assignment surveying postwar American art to exclude all but “Painting In New York, 1944 1969.” In view of our West Coast identity, record of and commitment to local support, his was discriminatory conception. We were to inaugurate our new building with a show that would not acknowledge the enterprise of West Coast artists, for over 40 years proudly featured by the museum (Kienholz, Turrell, Irwin, Chicago, Wheeler, Thiebaud, etc.). Neither Solomon nor Rowan, 10 of whose paintings were in the exhibition, would allow it to be modified. Only upon my rude protest to the executive committee, was $5,000 allotted to mount a lame grouping of the artists that had made the West Coast significant in contemporary culture.

It is perhaps tedious to chronicle all the physical headaches entailed by the museum’s move to its new quarters. From the lighting, to correcting paint choices, to boarding windows for wall utilization, to fending off eager cocktail parties while plaster was still being troweled, the countdown atmosphere grew more and more nerve-wracking. With its bizarre space and curved walls, Ladd and Kelsey’s design resisted sane installations. I should mention, also, the sudden harassing of city officials and fire inspectors, who lent an unconstructive hand to the proceedings. (These cavils were spurred on by the architects, who felt that their building was sullied by those who required it to perform its function.) Twenty miles to the west, meanwhile, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art was about to experience its own debacle at corporate hands, in the “Art and Technology” exhibition, while earlier, across the continent, Alan Solomon had had a heart attack and died. Somehow, Pasadena got everything together, and opened to congratulating hordes. Only the Los Angeles artists, in a foul mood, quite rightly bad-mouthed the way they had been treated as second-class citizens. All this disorder and wretchedness, which had produced a sterile and forbidding building, elicited from the trustees a cavalier benevolence. Their good spirits, of course, had all along been relieved of practical responsibility, and were in any event innocent of the taste to inform it.

From my point of view, the aftermath of this gala was in dreary and squalid character with all that had preceded it. Upon my return from New York and preparation for a Judd exhibition, Rowan informed me that he was substituting an expensive Warhol show in its place. The president of the museum had blithely bypassed the art committee to arrange a project with a private dealer. Since the Warhol would be bracketed by an earlier Stella and a later Judd exhibition, Pasadena was to look very much like the Western headquarters of Leo Castelli. In true form, Rowan sold two Warhols for about a 1500 percent markup, and with each rise in that artist’s auction sales, owners would frantically contact us with escalating insurance estimates to accompany their loans. It was very much like the Dow Jones breaking new records.

By the beginning of 1970, it was clear that the museum’s financial affairs were in a shattered state. Pledges weren’t coming in fast enough to pay the interest on the building debt, which alone amounted to some $10,000 a month. Expenses were enormous: the air-conditioning plant cost $12,000 a month to run, and the platoon of 17 guards, at an annual salary of $100,000, was sucking the museum dry. These expenses had to be met before salaries were paid to the office, curatorial, and educational staff. Then there was the exhibition budget, insurance and other general costs to be paid. True, the $2.00 entrance fee produced a good income at first. But once the novelty of the new museum wore off, it fast became obvious that the audience would not much exceed the 300 to 400 weekly that had visited the old museum. Though the museum’s attendance was always small and was to remain so once the excitement of the new building wore off, it was nevertheless a unique focal point for the Southern California art community, especially the museum’s openings. Los Angeles is a highly urbanized but nonetheless diffused area. Unlike New York, common meeting grounds are virtually nonexistent. Consequently firsthand contacts across generations and professions are extremely rare. The museum’s openings were more than social events. They brought together a large array of people from all over Southern California who normally had little contact with one another, but a strong common interest. The openings engendered a rare intimacy, which broke down, if only for a single night, the sense of isolation that the L.A. art community felt.

Although Terbell was worried and harassed as acting director, he felt optimistic about the museum. I did not share this view, since the financial problems were accelerating so rapidly, and there was little evidence of rational decision-making by the board. Terbell had more than once told me that, given his background as vice-president of a well-known bank, and his close relationship with Rowan and others on the board, he could see no real objections to himself becoming permanent director. There was no money to bring in a professional director from outside, one who would be prepared to cope with the impossible financial situation, and since Terbell was personally prepared to put money of his own into the museum, I agreed that his appointment might be the answer. Perhaps better communication with Rowan might help, since Rowan seemed uninterested in hiring a professional director. It might force him to relinquish some of his control.

The day before the board was to vote on Terbell’s appointment as director, he took me aside and with some anxiety told me that the word had come down to him that unless I resigned, he couldn’t become director. Would I please resign? I told him I would think it over and give him my reply that afternoon. When I returned, Terbell told me he had changed his mind, that he didn’t mean what he had said that morning. I told him it was too late. The long exhausting hours, the constant killing pressures, Rowan’s persistent and arbitrary interference made Terbell’s offer too attractive, however he might want to renege. The next day, he was appointed director by the board.

In February of 1970, I sent my letter of resignation to all 32 trustees,setting forth the problems of the museum. The new museum was operating with less than half the professional staff of the old, while often working as much as 112 hours a week; salaries were pitiful; it was impossible to operate the Oriental wing without a staff and a budget; trustees had accepted gifts on behalf of the museum without consulting the staff; several of these works had in the past (mainly 19th-century American) turned out to be of dubious authenticity, or outright fakes; and monies from deaccessions had not been spent on buying other works of art, but on operations. The majority of the trustees, I maintained, didn’t understand the matters on which they were voting. I suggested a complete restructuring of the board ‘s operating procedure to obtain better communication with the staff, and a more rational decision-making process.

Terbell, at a loss to mount approved exhibitions, approached me once again to guest curate them on a contract which I accepted. This arrangement was honored only until a replacement could be found for me. Terbell caught William Agee, a curator at MOMA, the very day he was resigning there, and suggested that he come to Pasadena. The job title was changed to Director of Exhibitions and Collections, and Agee took over. Rowan had reached the statutory limit as set forth in the museum’s articles of incorporation, and so stepped down as president of the board at the 1970 annual general meeting. Rowan was given the honorary title of chairman of the board, and Alfred Esberg, a tough local businessman, was elected president. About six months later, I left for New York to assume the editorship of Artforum.

In late 1970, Esberg and Agee united to fight off the inevitable — it was to be the last struggle for the life of the doomed institution. With Rowan now in the background, Esberg could make unsentimental reflective decisions in an effort to save the museum. Although Esberg was not a cultivated man who understood the deeper issues at stake, Agee was. But Agee was not prepared to lead what looked like a losing battle. When he pulled out to take the directorship of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, the last faint hope of saving the Pasadena Museum went with him.