That night, there was a Jack Smith performance at Artists Space and Jack and I were both there. The performance was slow to get started. A seemingly intoxicated Jack Smith, after arriving an hour late, unpacked an ironing board, a roll of film and a bunch of slide mounts, and announced that he just had to mount all the slides and then the performance would begin. While we were waiting, Jack and I talked about some of the performances I’d been seeing and about art. Jack was impatient and critical of Jack Smith and his ambling, messy, persona-intensive art. He dismissed the work of Joseph Beuys in the same breath.

Jack invited me to see some films he’d recently completed. We walked the few blocks to his place where he threaded film into a turquoise-coloured 16mm projector. Most artists’ films at that time were Super-8mm or video, so the use of 16mm in itself seemed like a novel choice. The film crackled, the numbered leader flickered by and the screen filled with brilliant colour. The Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lion, caged within the logo’s familiar armature, turned his head, roared, blinked, turned his head and roared, and blinked again.

As the short sequence repeated, the once familiar logo became stranger and stranger. You began to notice nuances in the facial expression of the lion. A moment of what seems like doubt or hesitation crosses the lion’s face, but is it before or after he roars? And what does that mean if it is before or after? Then, the sound seemed to detach from the image. The majestic lion roars, an icon heralding a fine cultural product which I’d seen countless times before was now made irretreivably suspect. I thought I knew exactly what it meant, but because of its brevity had always come in under the radar, continually unexamined. What was accepted as conventional suddenly seemed utterly bizarre – what is that lion doing inside of that oddly constructed space and what does it mean? To look at it over and over was like a portal into another dimension of time/space. I felt like Alice Through the Looking Glass, in a world that was very familiar but somehow turned inside out. I was completely blown away.

Jack Goldstein, still from A Ballet Shoe, 1975. 16mm film, 19 sec.

The next film began: a close-up of ballet dancer’s foot standing on point. It is static for some time, then two hands enter from the sides of the frame, untie the ribbon on the slipper, the ribbons fall and the foot collapses down. The collapse of an iconic image again. The next one: a sharp stainless-steel knife horizontally bisects the frame. It is glimmering and shiny. Jack joked about it being his version of Roman Polanski’s film

Knife in the Water. A colour appears reflected in the metal handle of the knife. Moving horizontally, the colour gradually pours into the blade of the knife, and then quickly disappears. Another colour appears and then penetrates the entire knife, then another and another.

The films were the length of television commercials. And they were spectacular. The production values were very high, in marked contrast to many artists’ films, videos and performances of the period, which tended toward poor quality as if to challenge one’s patience and endurance. It was almost as if there was a kind of aversion to acknowledging or referencing the level of perceptual sophistication we had all come to expect from watching television commercials and feature films. Jack’s work opened a door into what had seemed like a solid wall. And it had the potential of being deeply subversive. It could go into the belly of the beast (advertising) and use its vocabulary, strategies and seductions to examine the gaps between memory, perception, intention and expectation.

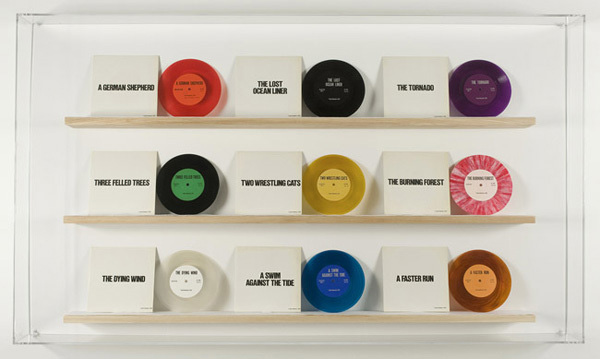

After the films, Jack got out a small black box containing a set of 45rpm records. Each 45, pressed in a different colour of plastic, had a professionally printed label. First he put on

A Barking Dog. I believe the record was red. You hear a dog barking. It’s quite a distance away, perhaps a few doors down or in a neighbour’s yard. It’s a lonesome sound. It conjures an image. It is a sound that exists in everyone’s memory. The distance has meaning, is almost palpable. Jack always used to say ‘distance equals control’, which I understood to mean that as an artist it was a matter of finding the right distance from which to examine things. That distance had something to do with the proximity of beauty and terror – of the sublime.

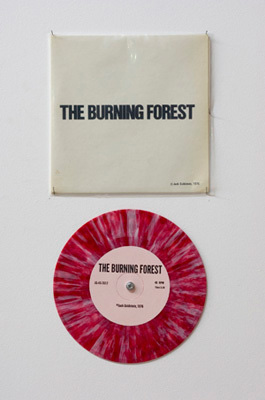

Jack Goldstein, A Suite of Nine 7-Inch Records with Sound Effects, 1976 (detail).

Next he put on

Three Felled Trees, a green record. You hear some chopping, then a tree falling. Then some more chopping, then another tree falls. Chop, chop. Chop, chop, then the record ends. In order to hear the final tree fall, you have to turn the record over. The interrelatedness of expectation, imaginative space and physical space was extraordinary, a kind of spectacle unfolding within my own mind.

And then there was

A Lost Ocean Liner: the mournful sound of an ocean liner going round and round and round, calling out from the black grooves of the record. The word ‘lost’ in the title connotes an undetermined path; yet as I watch the record turning, the ocean liner seems not so much lost as caught in a predetermined circular pattern. I think I know where it is; it just doesn’t know where it is.

That night changed my life. There was sense of immense possibility. Art could be powerful, beautiful and important. I was inspired to begin making art. In the twenty some years since that night, I have been inspired by many works of art, but nothing comes close to the experience of that night.

Much to my surprise and elation, he gave me a box of the 45 records. I was so delirious and carried away with ideas that I left them in the taxi. I spent hours on the phone with the taxi commission and at the police precinct on 5th Street filing a report for missing property. The police officer looked at me quizzically: a box of coloured records? Of what? Dogs barking? I’ve often wondered about where those records wound up, what they might have meant to the person who found them. Like the lost ocean liner, the lost box of records is out there somewhere in the world, sending a message into deep space.