Remembering John Baldessari

by Thomas Lawson

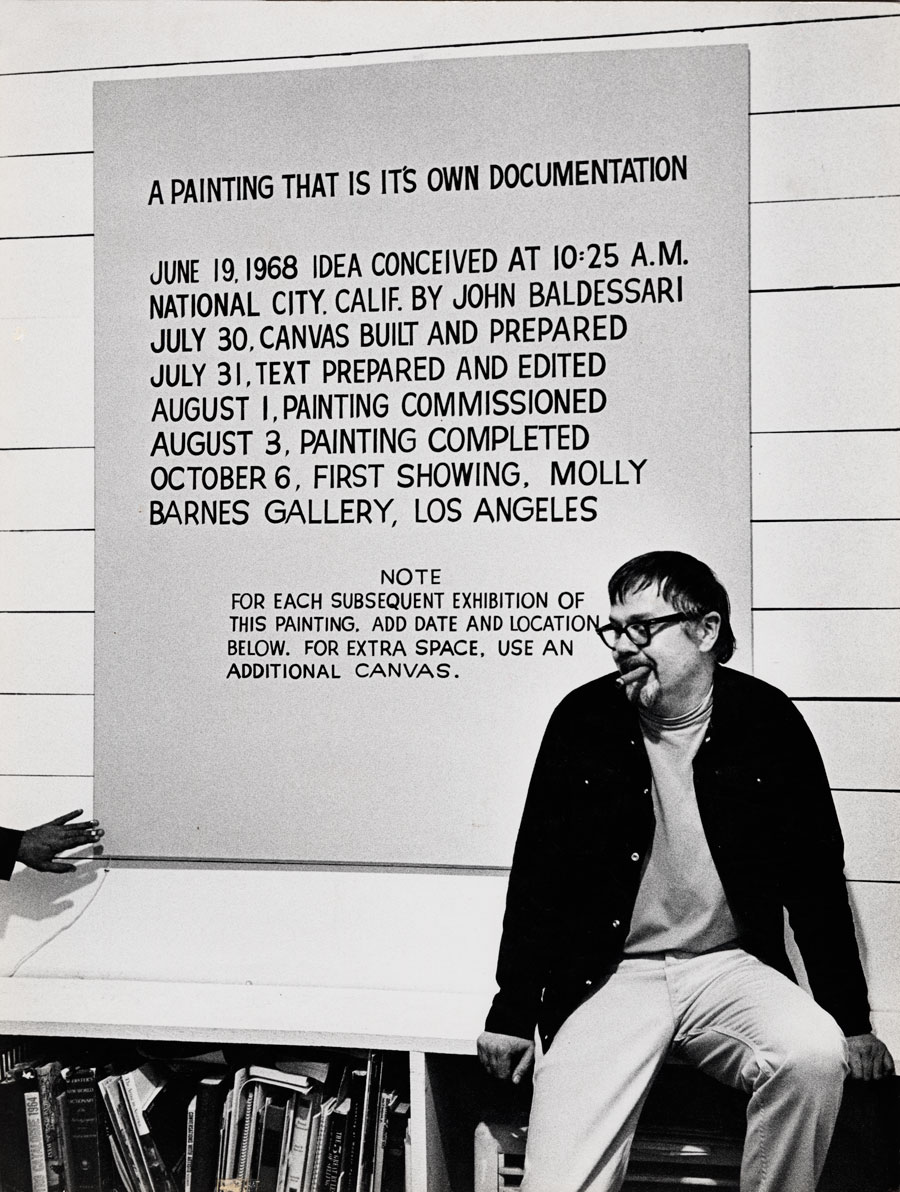

John Baldessari at the opening of his exhibition at Molly Barnes Gallery in Los Angeles, 1968. Photo by Phillip T. Jones and courtesy of Baldessari Estate.

In the days following John Baldessari’s death in early January this year, I dug into my archives looking for something to re-post on East of Borneo in his memory. I was pretty sure that I had written a catalogue essay for him, but it was from a time before digital files were effortlessly saved. So nothing showed up on any hard drive. Eventually I tracked down the catalogue, for an early survey show called “Ni Por Esas” at IVAM, the contemporary art museum in Valencia, Spain. The curator was a young man called Vincento Todali, who had just finished at the Whitney Program in New York, and who, I now remember, smoked continuously, as did nearly all of Craig Owens’ devotees from that time. I must have spent a week in Valencia, to discuss ideas about the show and we mostly met outside, on the plaza, so that he could smoke and I could breathe. The catalogue is nicely designed, but modest. My essay is printed only in Spanish.

Another week of digging around in dusty folders, and finally I unearthed a slightly worn print out of the manuscript. It was long, well over 5,000 words, with a post-script threatening more to come. Oy. I sat down to read it and discovered that the first half was a very 80s polemic, clearly aimed at rebutting arguments that Craig had been making against the kind of post-modern attitudes towards representation that John championed. The second part was the more straightforward description of some of John’s earlier work that follows here.

There is something about this story that speaks to the randomness of remembrance and the trials of translation. I think John would have enjoyed hearing it, and I’m sorry I couldn’t tell it to him.1

***

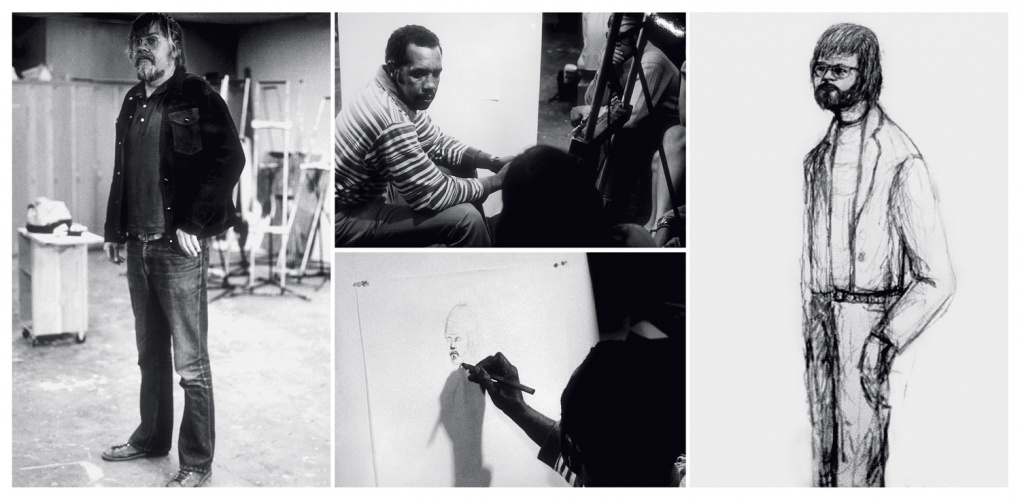

Sometime in 1971 John Baldessari visited a drawing class being taught by a friend in Los Angeles. His friend was not in the room, and Baldessari hung around for about ten minutes, pretending to wait, and then left. Shortly afterwards the teacher returned to the class accompanied by a police artist skilled in making portrait sketches of suspects from the usually inadequate descriptions of witnesses. The teacher asked the students to describe the stranger who had just left, and the police artists made a drawing. Baldessari then returned and had a photograph of himself taken in a pose approximating that of the drawing. The final piece then provides us with differently misleading representations of the artists. On one level this provokes a question of veracity — which image is more believable, which representational technique more reliable? — on another it asks a broader question about the image of any artist — who is this interlocutor? — criminal? innocent bystander? trickster? teacher?

This piece, entitled Police Drawing, is typical of Baldessari; a skeptical, waggish demonstration of the limits of art performed in such a way as to question, but ultimately affirm, the place of art within our culture. Baldessari’s humorous pedagogy replaces the discourse of contemporary art, at first removing it from its privileged sphere apart from daily life, only to return it after a loopy, not quite focused examination. Repeatedly Baldessari questions the common assumptions about art, foregrounding their arbitrariness, their ridiculousness. His method of repositioning is a variety of montage, its purpose to produce what Roland Barthes has identified as a new intellectual art characterized by the simultaneous existence of “theory, critical combat, and pleasure,” in which the objects in play are not subjected to a search for truth, but to a consideration of effects. 2 This method of working, in both art and criticism, shuns the simple finality of the masterwork in favor of a discursive model that remains incomplete and full of digressions. Such a model, shunning the certainty of conclusions, calls for the juxtaposition of fragments, half-told tales, random details and gratuitous close-ups, drawn from every level of contemporary experience. This method is discursive, but its progress is marked by constant interruption. Discontinuity and unbalance are found to be more productive, somehow more accurate, than the smooth flowing voice of modernist authenticity.

Police Drawing, 1971. Conte Crayon on paper, three black and white photographs, and video. Drawing: 39 X 23 1/4 in. Photos: 7 1/4 x 10 1/2 in. Courtesy of Baldessari Estate.

Police Drawing comes roughly halfway through a ten year investigation of the methods and assumptions of art making, a period in which Baldessari can be seen to educate himself by unlearning the unthought postulates that still remain the common currency of too much thinking about art. Prescriptions are systematically violated, hoary advice routinely put to ridicule. The first essays in this deconstruction of art dogma were modest in scope, a selection of texts and photographic images reproduced on plain white canvases. The texts offer a range of prescriptions and high-minded phrases culled from a variety of art books, the photographs ineptly flaunt the rules of composition these same books promote. Neither text nor image is actually placed on the canvas by the artists, only by his instruction. In a later series the images, again based on some rather inept photographs, are painted by amateur artists. Despite their radical intent, these works, by insisting on their identity as paintings, remain less adventurous than the language games played by the likes of Mel Bochner and Lawrence Weiner at the same time in New York. But when Baldessari moved from San Diego to Los Angeles in 1970 to join the faculty of the newly constituted CalArts, he found the ideal context in which to expand his pedagogical conception of art making.

Freed of a perceived need to work within the framework of the art gallery, Baldessari began a far-reaching exploration of the semiotics of art production and perception. The works of the early 70s operate as a series of demonstrations, like so many home experiments, in which the gamut of aesthetic propositions are put to test — the specific test often quite preposterous. By way of example one need only look at the titles of some of Baldessari’s wars from the period — Throwing Four Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (Best of 36 Attempts), Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get an Equilateral Triangle, Teaching a Plant the Alphabet, How Various People Spit Out Beans — to get a sense of this particular branch of paraphysics. In the videotape I am Making Art (1971)3, the artist moves different parts of his body while intoning the piece’s title, building a minimal choreography very much in tune with then current art practice which nevertheless makes fun of an endemic solemnity. Or in the Choosing series of the same year he asked friends and students to pick out three green beans, carrots, onions, stalks of rhubarb, radishes from small piles. He would then take a photograph of his finger pointing out the ‘best’ of the chosen items. In another videotape, this from 1972, he sings a series of numbered, highly complex definitions of conceptual art written by Sol Lewitt to the tunes of such hackneyed numbers as “Camptown Races” or “Some Enchanted Evening.”

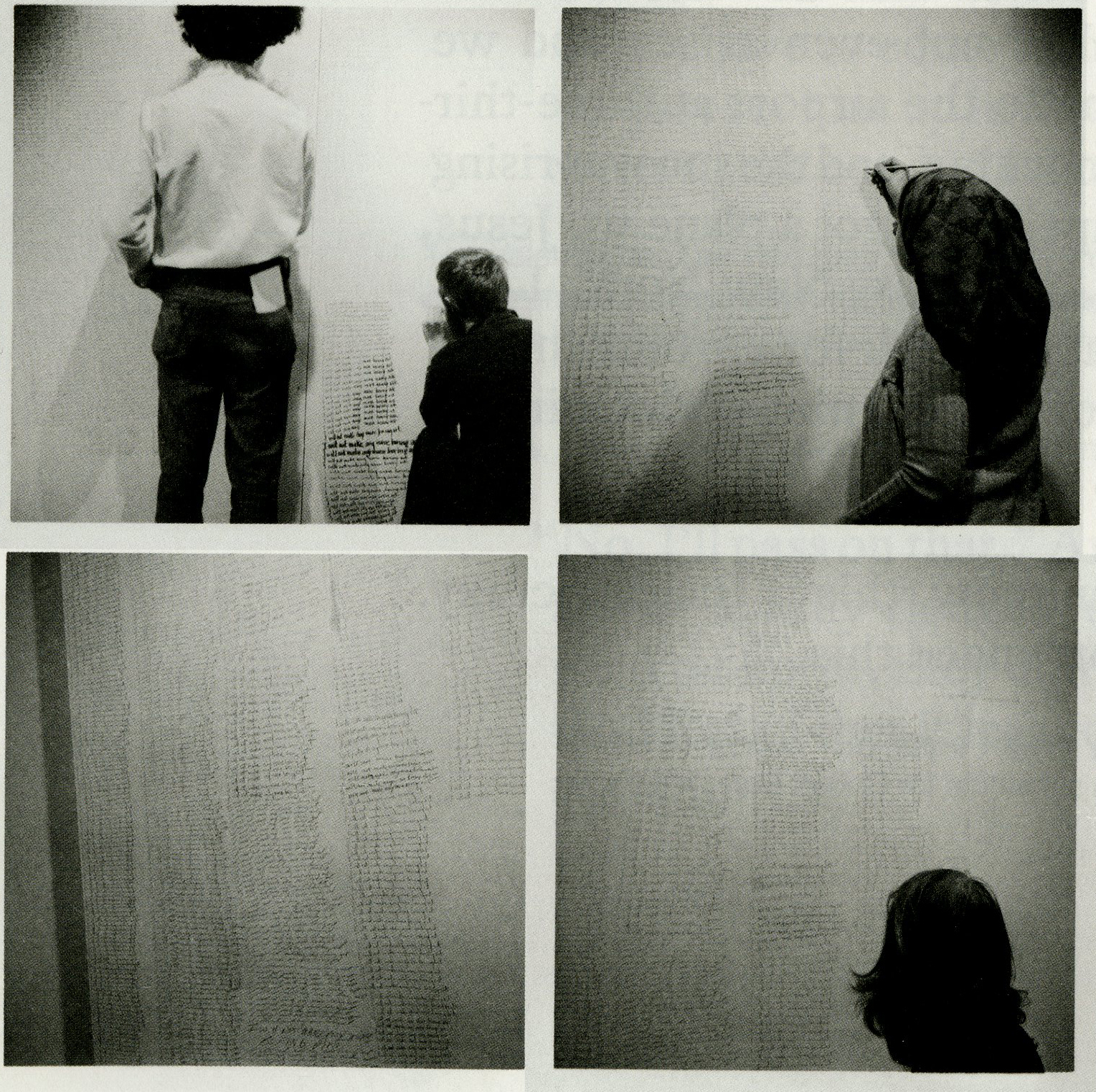

Asked to participate in an exhibition in Nova Scotia by an art college unable to pay airfare, Baldessari sent instructions that the students be asked to write “I will not make any more boring art” on the walls as many times as possible. Punishing the students for the shortcomings of the college administration, he also confronted them with a paradox; the execution of the work was undoubtedly boring, but the idea and its reception both very quick and funny, presenting a series of conundrums surrounding the identity of the artist and his presence in the work. This ironic removal of the creative hand of the artist (a gesture further complicated by the subsequent completion of a videotape and lithograph incorporating Baldessari’s handwriting) postulates an engagement with Roland Barthes’s deconstruction of the ideology of a privileged author and suggests the range of Baldessari’s ambitions even in these relatively early works.

What we have then in the body of work so far is a concatenation of ideas surrounding an investigation of the end of individualism as such, and the ramifications of that end for art and artists. Again and again the pretensions of the great modernisms, with their necessary certainty of the uniqueness of the individual’s experience, is put to a rather mundane test. The very randomness of contemporary life, the arbitrary repetitions and eclipses of the post-industrial landscape, are shown inexorably reducing art to mere play, and often not even very sophisticated play.

The clarity of Baldessari’s position, its usefulness, can perhaps better be understood in noting the difference between his practice and that of another artist/teacher, Joseph Beuys. Baldessari’s textuality is a liberating procedure, one that invites active participation both in the construction of the work and in its reception. The ideology of meaning — its structure, its authority — is put into question, repeatedly. A series of games and ploys are devised to unbalance certainty, to rephrase the obvious. Beuys, on the other hand, uses the ideology of liberation simply to set up a parallel academy using the authority of his mythic self-image as a survivor/savior as the legitimating force. The Beuys action is not as open ended as it appears, but merely a grouping of mystifying pronouncements from a self-appointed leader confident in his own truth. The problematic of individual experience in a mass-based consumer culture is finessed, but not addressed. Both artists are part of a larger movement interested in transcending the constraints of the marketplace on art, and both are interested in replacement of art within a de-structured academy. But whereas Beuys simply proposed to insert himself in the place of the older, to-be-dethroned masters, Baldessari sought to empower his audience, to include them in construction of meaning.

Installation of I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art at Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax, 1971. Courtesy of Baldessari Estate.

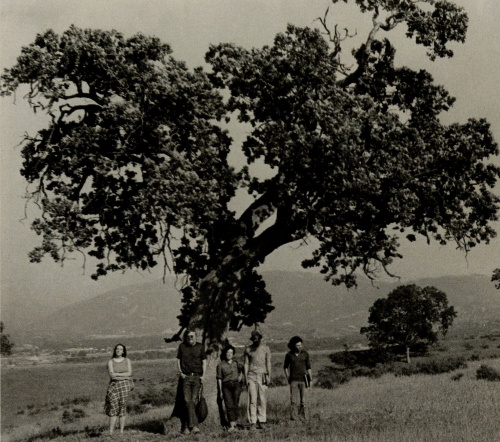

John Baldessari and CalArts students Dede Bazyk, Suzanne Kuffler, Matt Mullican and David Trout during a project called Rolling: Tire in 1972. Photo by James Welling. Courtesy of Baldessari Estate.

By the mid-70s this work of deconstruction had reached an endpoint, all that could be further expected was an increasingly refined reiteration of well understood discoveries. The hidden ideological structures which kept artists trapped maneuvering between stylistic change and stasis were now plainly revealed to all who looked. The task was now to do something with that revelation. But what? The step was readily available. The work already accomplished had gouged the stinking corpse of subjectivity from its lair in the heart of art, revealed the processes by which it hypnotized the seekers of transcendent truth into believing that its trivial presence meant something. What yet had to be done was to transfer that insight into the wider world of public representation, to develop an art that would talk not merely of the inadequacies of art, but the insidious seepage of the ideological into the psyche from all aspects of the media spectacle.

From the mid-70s Baldessari began to return his work from the experimental realm of the classroom to the more public (relatively speaking) arena of the gallery. A working procedure had been worked out, it was now time to develop its consequences. There was also an interior logic driving the work back to a situation in which issues of display had to be met. Increasingly Baldessari had been making an issue of the presumed rawness of his material, using press photographs and movie stills to underscore the inescapably cultural quality of the work. The loosely structured demonstrations became formalized and took on more nearly the calculated look of art. No matter the form, the pieces themselves remained about seeing through the veil of culture. They purpose to tell us something, a story, a joke, a riddle, but actually tell us something else. The jokes and stories never quite cohere, they lack a defining moment. But of course they are not about telling stories, exactly. Rather they are about the difficulty of getting art to mean anything useful. In a piece like A Different Kind of Order (The Art Teacher’s Story), the viewer is offered a number of newspaper photographs of disasters ‘artistically’ arranged along with a short statement about keeping art students off balance by having t paint while standing on one leg. The abrupt assertiveness of the photographs rocks the relative gentility of the schoolroom trick. Neither element quite adds up, but together they present a play of sorts, a game about the self-engrossed pointlessness of the game itself. The piece works as an allegory of meaninglessness.

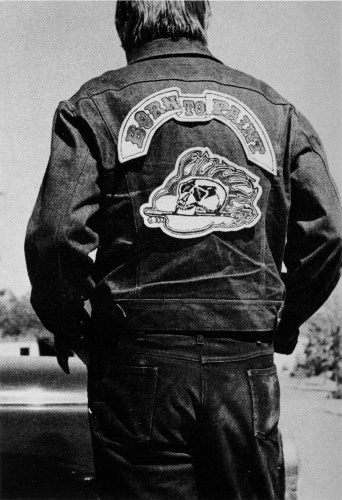

John Baldessari wearing Born to Paint jacket, late 1960s. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Baldessari Estate.

Having long been consigned to the ash heaps of history, allegory has recently enjoyed a comeback. It has become hip, the only suitable trope for a time like ours. Allegory insinuates itself into intellectual life when nostalgia becomes respectable, and nostalgia has steadily become the guiding principle of fashion, entertainment, politics. Allegory involves a certain reclamation of a past considered beyond recovery, a neutral technique that allows the reuse of one thing to suggest another. Material is in a sense confiscated, with the premise that it will be brought to life anew, given new meaning. But that promise is repeatedly deferred, for allegory springs from a melancholic dissatisfaction with the inadequacies of interpretation. The allegorist mourns the lack of meaning apparent in cultural life. But the allegorist’s pleasure is not to fill that loss, but to postpone the moment of its fulfillment. The allegorist seeks the pleasure of returning again and again to the delicious contemplation of desire. Satisfaction would be ruin.

For Baldessari that meant a recuperation of the surrealist cut, a return to Bunuel’s viciously erotic gaze. But whereas Bunuel was still preoccupied with the dreams of a privileged self, Baldessari began to investigate the mass produced dream whose record is kept in the archive of Hollywood, and the intersection of that dream with the idealistic fantasies of modernist formalisms. In the Violent Space series, possibly the first body of work to fully articulate this heartless allegorical technique, Baldessari uses the vignette as a device of focus, exaggerating the violence of the cut made by the photographic frame. Detail is revealed forensically, laid bare on the operating table of high art formalism, where it is revealed to provide only the most inadequate of clues to its significance. What new can be learned from looking at three faces with closed eyes, or five with clenched teeth? Detail feeds ambiguity, the image remains resistant to anything like an accurate interpretation. The renewal of context, its replacement with the artifice of display, highlights the same problems of visual understanding raised in the earlier work, but in a more elliptical, more slippery way. By focusing on detail, zooming in on the close-up, an apparent clarity is interrupted. The lugubrious teasing of meaning evident in the earlier work, the desire to get at something, is abruptly shown up as duplicitous. The desire is not for that kind of closure, but for a continuation of the game. The jokey semiotics ultimately refuse the ‘authority of the crypt;’ they are just a tease. As is the more fully developed deconstruction of the panoply of found imagery; the libidinal center of the work is not the discovery of truth, but the joy of looking. It is concerned with, and participates in, the erotics of the gaze.

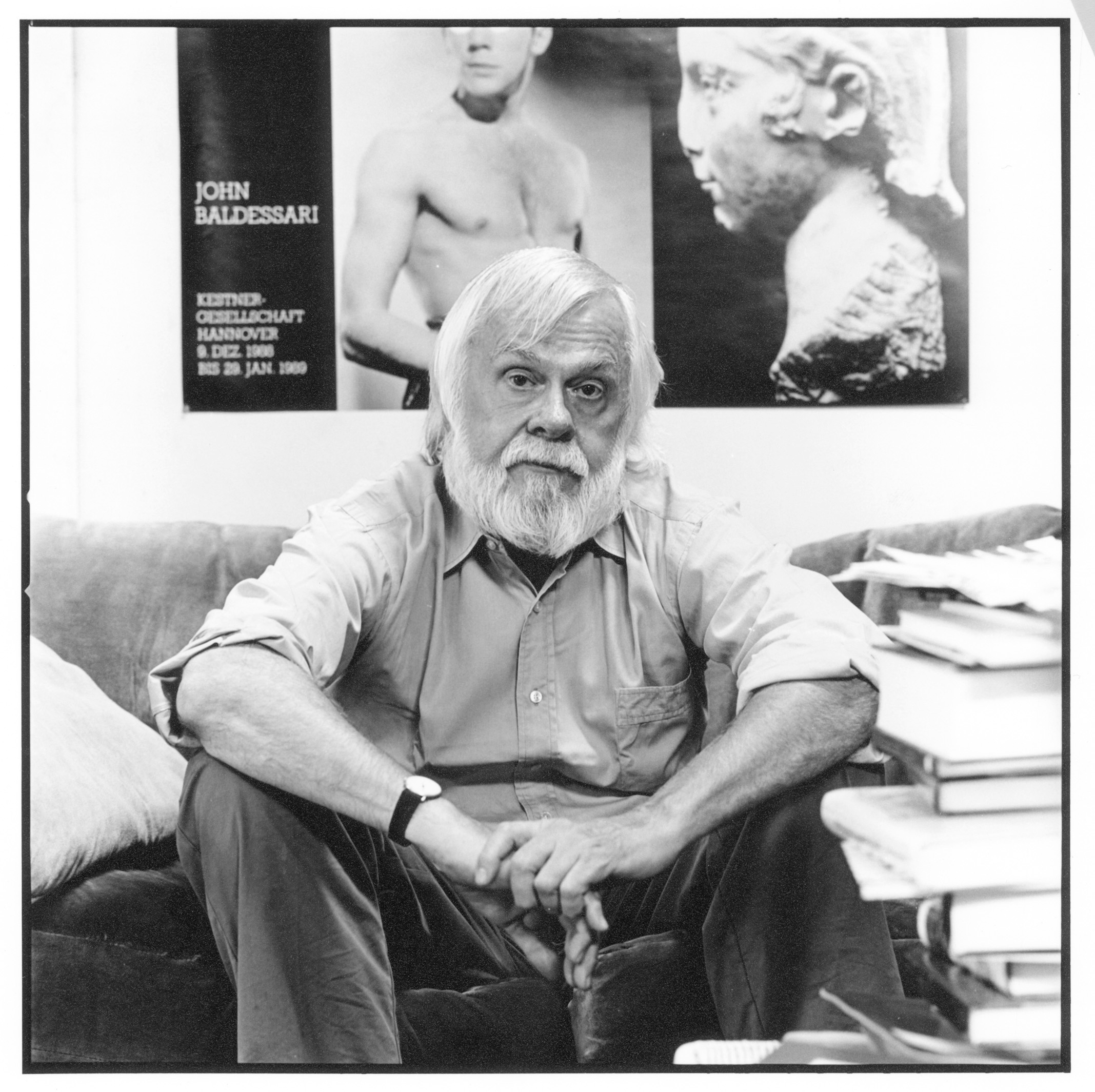

John Baldessari, 1982. Courtesy of Baldessari Estate.