Scanning the Landscape: An Interview with Aurora Tang

by Kate Wolf

CLUI photo from the Morgan Cowles Archive. Courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

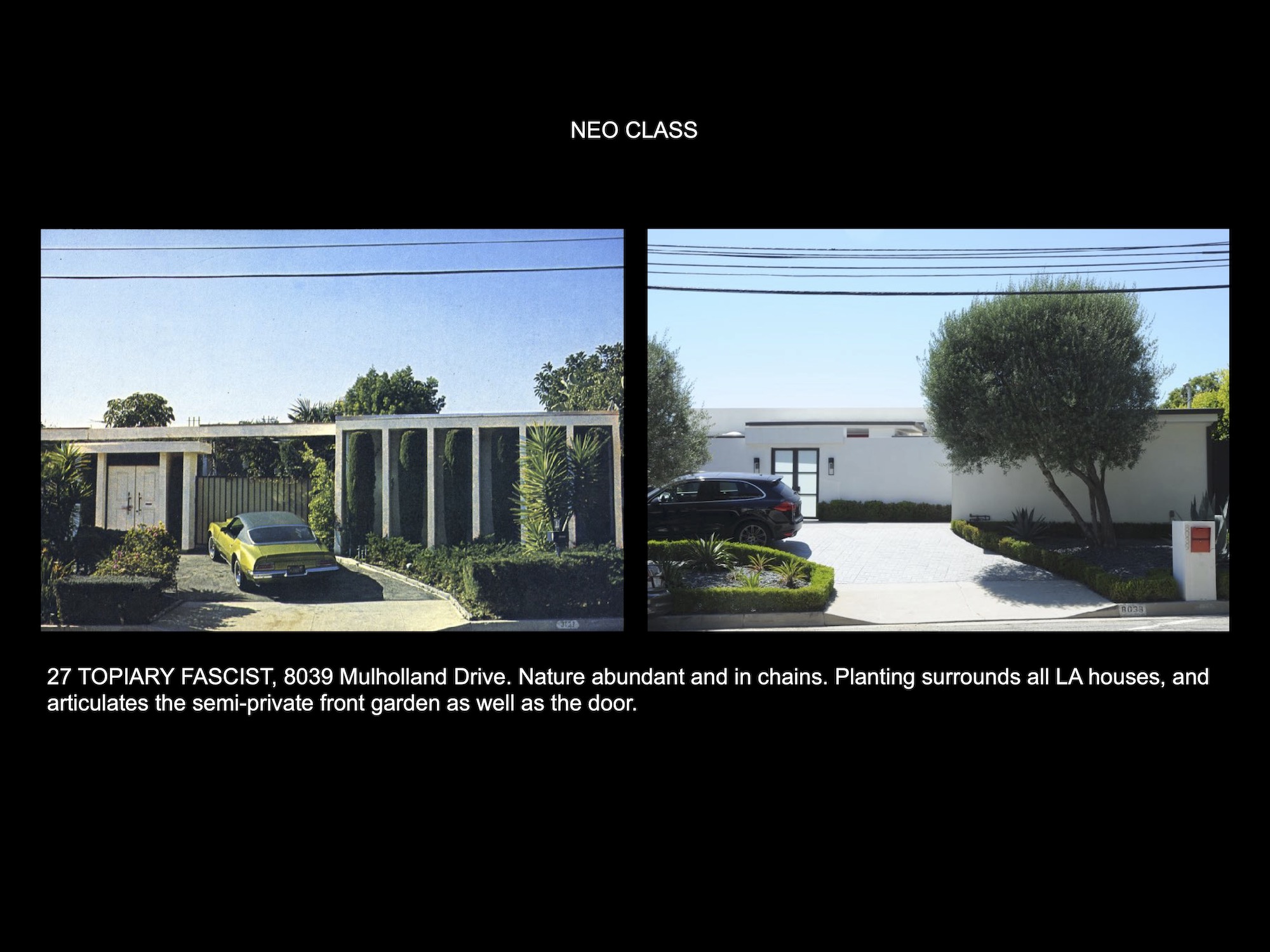

Aurora Tang is a curator and researcher working at the intersections of Land Art’s legacy and site-specific installation, architectural criticism, history, photography, and the imperative of ground-truthing. (The term, borrowed from geography, means simply knowing places through firsthand experience of them.) Since 2009, she has worked for The Center for Land Use Interpretation, an organization that exemplifies all of the above, and is nearing its third decade of operation. Currently Tang serves as CLUI’s program director and, from 2011-2015, was also a managing director for High Desert Test Sites. Over the last year she has curated exhibitions of the artist Kristin Posehn’s architectural sculpture, and contemporary plein air painting; and with CLUI, of everything from old postcards of California to pumped storage hydropower plant sites in the U.S. Though I have known about her work for a long time, I became desperate to speak to her when I saw, belatedly alas, that she had given a presentation on one of my favorite books about L.A., Daydream Houses of Los Angeles, by the British critic Charles Jencks, at the MAK Center for Art and Architecture. Tang presented her own rephotography of the many eccentric houses that Jencks shot and featured in his original volume from 1978, which he peppered with an inspired taxonomy, describing houses, for example, as “Topiary Fascist” or “Baby Blue Lobster With Corner Frosting.” We spoke about this ongoing project as well as her work with CLUI at her house in mid-city, only occasionally interrupted by the acrobatics of her two extremely vivacious cats.

Kate Wolf: When I initially approached you about this interview it was for the Artist at Work series. That was kind of a blatant misunderstanding on my part, because you clearly identify as a curator and a researcher—you’re not putting yourself out in the world as an artist. But you also seemed adamant that the Center for Land Use Interpretation doesn’t belong in an art container either, and I was curious about why. Why does that seem like the wrong category and what does it get wrong about the project? How would the meaning of your work or the Center for Land Use Interpretation’s work change if we were approaching it as art?

Aurora Tang: That’s a good question and I guess I’ll speak for myself first. My training wasn’t as an artist, so I have always been a bit reluctant to identify that way even though I recognize some of my projects are fuzzy. I’m totally fine with other people interpreting what I do as art, or something else, because art is a wonderful catchall for things that don’t fit neatly in other boxes. But I guess I became drawn to the role of researcher because it seemed more open-ended, and part of it is that I also have this curator hat. I don’t want to step on anyone’s toes, and I try to keep different hats and try to set up boundaries when I approach different projects. I use that word “projects” a lot too, for lack of a better word, but for some of these things, like this Jencks rephotography project, I was really reluctant to even name it because in naming it something inherently changes about it. I used to say I was a creative researcher, which is very similar to an artist, I think.

KW: Or a writer.

AT: Or a writer, yes. About 10 years ago I was thinking of some of the fuzzier projects I was working on that were independent as “creative research projects,” but I just got rid of the creative because it seemed redundant; “creative” is inherent in everything. I like the word “research,” though. It’s a process that’s understood across disciplines. In academia being a researcher is maybe seen as a more lowly or junior level position, but it’s one that I feel like everything can be approached as. I consider the photographs I take as more toward research rather than as photographs in and of themselves.

KW: What did you study in school? What’s your background?

AT: I studied art history and journalism at USC. I got really into 1960s and 1970s American Land Art through Thomas Crow, who was a teacher of mine—that’s how I got into the Spiral Jetty, into Smithson, so many people. But before then I had this interest in visionary art environments, what are sometimes called folk art environments, really just spaces that are not by trained artists; when I moved here from the Bay Area for school, it was so exciting for me to learn about Salvation Mountain or Noah Purifoy. I only took one art class. It was a black and white basic photography class taught by Robbert Flick, who I wasn’t familiar with except he had this show at LACMA, Trajectories. And I remember seeing it and then recognizing his name in the course catalog and being like, “Oh, wow, I can take a class from this person.” He’s actually the one who introduced me to the Center for Land Use Interpretation. I think it was my last year of undergrad and because of the photos I was taking he said, “Do you know about this organization?” I had been to the Museum of Jurassic Technology (which is next door to the Center for Land Use Interpretation) but didn’t know about the Center, so I checked it out and just couldn’t stop going.

I did go to grad school, also at USC, in their curatorial studies program—it was called Public Art Studies at the time. I graduated from that program in 2010. I would say it was very much a hybrid; it was a very institutional critique-heavy program, but also with some nuts and bolts stuff about public art—how to do proposals, things I’ve come to appreciate. And it was also open enough that I got to take some geography classes as well.

I feel like I was really fortunate being in L.A., especially as an undergrad. I just always had an internship and several jobs; I almost feel like it was a process of elimination. I interned and worked at Christie’s of all places; I worked at a commercial gallery for many years part-time, and that’s where I feel like I learned about contemporary art in a lot of ways. It was almost like, okay, maybe this isn’t for me, but I was getting glimpses of different facets of what they say you can do with my education. Eventually I was working at the Getty Conservation Institute and Getty Research Institute, and I thought that was what I wanted to do. But when I started learning about these smaller spaces that L.A. seemed to have a lot of at the time, that seemed quite unique to the city—the Center for Land Use Interpretation, the Velaslavasay Panorama, the Museum of Jurassic Technology, and Machine Project, which was fairly new—they made me want to stay for grad school, really more than the program.

Installation view, Time Stamps: Revisiting California Through the Postcards of Merle Porter, Todd Madigan Gallery at Cal State University Bakersfield, March 10–May 7, 2022. Image courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

KW: What was it about those spaces that drew you to them?

AT: I think it was that I was coming from working for these really large institutions where there can be this punting culture. Large institutions are wonderful, and I feel very fortunate I still get to work with them in different capacities now. But for example, at the Getty Research Institute, where I worked in publications, my job was really specific. I was given some information, I did my thing, and then I passed it along. You don’t always know what happens to your work, especially if you are in a more entry-level position. And there was something I found really exciting in that the director and founder of a small organization would have so many roles and do so many different things. Now I really enjoy knowing exactly where the resources come from for a project, following it along, nurturing it at every stage. I feel like that has been really rewarding.

KW: Going back to the question of art, I think it’s interesting to compare CLUI to a bigger institution. Because even if it’s not structured like that, it has such a definitive style and aesthetic and tone—what the critic Michael Ned Holte has called “the Administrative Sublime.” There’s just this anonymity to it; it has a political neutrality that is in keeping with lots of institutions. I always get a kick out of reading the newsletter where things that might otherwise be hot button topics are treated with so much remove. You’ll be talking about alternative energy sources or urban renewal or surveillance, but never quite getting into the conflict surrounding them. I’m curious about that unified front, the discipline of the way the Center presents itself to the public.

AT: I think I come to the organization from a different point of view than someone else, such as Matthew Coolidge, who’s the founder and still the executive director. I’m probably the only person in the current core team who has an explicit art background. That’s not to say others there aren’t informed by contemporary art figures or that we don’t consider ourselves an arts organization, we just think that we can also be other kinds of organizations, too. And I guess it goes back to that openness because one of the things we are trying to do, maybe the thing we are trying to do, is create a contemporary portrait of land use in the U.S. today. The U.S. is not just California, it’s not just Los Angeles where we’re headquartered, it’s all 50 states and territories, so I think the only way that it’s possible for me to do my job is to adopt an institutional persona.

You probably noticed the newsletter is collectively written by the organization. There are editors named, but it’s really an institutional voice that is different from my individual voice or Matthew’s. I have personal thoughts about a lot of the topics we’re covering, but those are for me to engage with in my own work. I go back to the Center for Land Use Interpretation’s mission statement a lot—which is “dedicated to the increase and diffusion of knowledge about how the nation’s lands are apportioned, utilized, and perceived”—almost as a guiding framework. And if something doesn’t make sense under that, then I can just do it as an independent curatorial project or research project.

When I learned about the Center for Land Use Interpretation in school, it was contextualized as institutional critique and an art collective. Which is a little different than my experience with it now that I’m part of it. I understand it being contextualized that way, but I feel like the Center is almost celebrating institutions and drawing and pulling from institutions with the capital I, the aspects of them that we feel are effective and work, and then maybe leaving behind the parts that are less useful, or even possible given our smaller size and capacity. It’s really showing what institutions can be rather than critiquing them, but I suppose they could be also seen as one and the same.

CalEnergy geothermal power plant, Calipatria, California, CLUI photo from Venting the Earth: Looking at Geothermal Energy, Center for Land Use Interpretation, Los Angeles, April 22–November 20, 2022. Courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

KW: What’s interesting to me is that the critique is never so explicit, but it does seem like it’s there, especially in terms of where attention is being drawn. CLUI maintains a facility in Wendover, Utah that was the home of the training program for the first atomic bombing mission that was later carried out in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There’s also a research center in Hinckley, California, which is most well-known for its contaminated water, and these tours of mining pits you offer. It seems like where you take people and what you invite them to look at are not exactly scenic sites and therein lies a form of critique.

AT: I think it’s also about asking folks, what are you paying attention to and what are you not paying attention to? What we do is just point to things with the intention of letting people know where they might look, often things are seemingly hidden in plain sight. But we don’t necessarily want to tell them what to think about these things.

It’s about guiding our audience’s attention in a way. More and more—and I think this has changed since the mid ‘90s when the organization was founded—discourse tends to be very hyperbolic. There’s a lot of shouting going on in social media and the news—everywhere. Not shouting is a strange thing to encounter, and it is a position as well. I like to think that people can come to their own conclusions about things, so I really appreciate having the Center as a framework to work within and to explore a lot of these really pressing topics.

CLUI photo from the Morgan Cowles Archive. Courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

KW: Are you ever torn about holding back a more pointed framing, though? Is that openness and porousness of, “Okay, here, we’re showing you this, but you interpret what it is or what it means to you,” ever difficult for you? Because sometimes people aren’t that smart.

AT: Well, in the first few years it really was, but over time I have been better at coming to terms with the fact that the impact of our work might be very, very slow and may not resonate with everyone at first. The Center’s approach is very hands off and not aggressive at all. We do very little PR or marketing, but I’ve come to really appreciate that. I worked at MOCA in the communications and PR department in the past and coming to the Center it was like, “Wow, you don’t send press releases out?” We didn’t even have a Facebook page when I started. I think I’ve also come to feel quite grateful that the Center operates in its own way; at a bigger institution you probably wouldn’t be able to not send out a press release.

KW: It makes me think of an article I read recently about the postwar German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, about how people get them wrong, that they weren’t just cataloging industrial structures and it wasn’t like they didn’t have a point of view.

AT: With the Center especially, our goal more than anything is to let the places speak for themselves as much as possible. Of course we’re very aware of the frame and the mediation that has to happen when putting together exhibits or publications or public programs, but I like to think of our approach of taking photographs almost like the Google Street View car just scanning the landscape, this eye that is a uniform point of view or perspective. In a way, we want it to be about the places so much that maybe it comes off like we’re trying to be anonymous, but that isn’t the case.

We also have an appreciation for found or readymade objects as well; it’s almost what we approach the landscape as. We have a couple collections at the Center of paper materials that were meant to communicate something and then be discarded after they had been used, all these pieces of paper that are literally picked up out of the trash. And then just by reframing them, we can find new meaning.

There’s one, this set of Rolodexes with business cards in them from Los Alamos National Lab [where the atomic bomb was developed]. We were on a trip in New Mexico and visited this surplus store that was operated by a fellow named Ed Grothus who worked for the lab during the Cold War. He would buy these lab castoffs from auctions; by then he was an ex-lab engineer who no longer believed in what he was doing, so he amassed this gigantic collection in an old supermarket in town. He called it the Black Hole because of the idea that all this information came in, and nothing came out.

Anyhow, his daughter was trying to get rid of everything, so she invited us to come by and we picked up some stuff for future projects. But I was also just so interested in the stationary and binders, just things I needed for the office. I remember seeing the set of Rolodexes. It wasn’t until we got back to the office and were unpacking things that I realized they were full of hundreds of different business cards from different people involved in the lab and weapon development at the time of the Cold War.

CLUI photo from the Morgan Cowles Archive. Courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

KW: Wow.

AT: Yeah that’s just one example. Another is the Coast Realty Archive, that’s our newest collection: thousands of real estate listings from the late fifties to seventies, all on the westside of Los Angeles. Each one is an eight and a half by eleven piece of paper, and there’s a photograph, or several photographs, of the property for sale at the time, taken from the street by, again, an anonymous real estate photographer, and then information about the property.

We began to think of that collection as a street by street portrait of the westside of L.A. at that time. It comes from the Coast Realty Office, which is actually right next to our neighbor the Museum of Jurassic Technology on Venice Boulevard. The sign is still up there, but it had been vacant for years. I had never seen anyone there. One day my colleague, Sarah Simons, was walking by and noticed the door was open and they were clearing it out and so we just asked if we could have them.

KW: In that project, what are you seeing beyond just this archive of a street or an overview of a place that has now probably changed a lot. Is there anything else you’re noticing that makes it feel particularly significant?

AT: Well, I think it’s interesting that the images you see often appear as if they were just shot out the window—these are pre-Google Street View images and sometimes they aren’t particularly good—but they’re capturing these properties at a time of change. They’re literally changing hands and sometimes they’re demolished right after the photograph was taken. The CLUI has started to present the Coast Realty Archive in exhibitions and programs, but we think of the Coast Realty Archive photographs as raw material—all of our research we approach as raw material for others or for us to then use and make into projects.

And so, for that one, we did a rephotography project as well, which was quite straightforward, because you have a precise address actually, so it’s easy to go to the exact site and try to frame it the same, to match up the horizon lines, the angles. And it became really an interesting exercise similar to the Jencks, although because it was on Venice Boulevard, a lot of it was commercial real estate. But you notice changes in landscaping certainly, in other trends, and the desire for privacy.

I think what’s consistent with that project and other Center for Land Use Interpretation projects is it’s just about getting people excited about their environment, whatever that may be. And Venice Boulevard is an important street, but in a lot of ways it’s unremarkable as well. I think just by pointing to these structures, these stucco boxes, and giving them attention, you really start to realize how special a lot of them are, and in a rapidly changing city.

Still from Time Stamps: Revisiting California Through the Postcards of Merle Porter presentation, April 26, 2022 (left: Merle Porter postcard; right: CLUI photo). Courtesy Center for Land Use Interpretation.

Still from Time Stamps: Revisiting California Through the Postcards of Merle Porter presentation, April 26, 2022 (left: Merle Porter postcard; right: CLUI photo). Courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation.

KW: On the theme of change, maybe we could turn to this Charles Jencks project that you did. I’m interested in what drew you to the book Daydream Houses of Los Angeles1 in the first place and why you wanted to rephotograph it?

AT: I stumbled upon the book, like many of my favorite books now, just by browsing the bookshelves at the library at the Center. And I was really drawn to its curious format. Charles Jencks put out a couple of these paperback books with an almost square format; another one is called Bizarre Architecture. I really appreciated how informal they seem—a lot of the photographs seem like he took them from his car—and I really appreciated his enthusiast point of view. And I love his descriptions, just how colorful they are.

I love houses. One of things I really enjoy about Los Angeles is the wide range of residential architecture. In my free time when I would go on walks in different neighborhoods, I was fascinated noticing these different trends and patterns, especially the castle-style, which you see everywhere in L.A. and in Burbank in particular, and in a lot of these studios or donut shops or tire shops. I was thinking maybe there’s something there: maybe it’s the proximity to Hollywood, or maybe it says something about the American dream and in particular the American dream in Los Angeles. And Jencks was getting at this, just this excitement I felt driving or walking around the city.

And so I got curious. Do some of these houses he photographed still exist? I started looking for them and would take a snapshot, at first with just my cell phone, if I found one. And when I got home, looking at my photo next to Jencks’ picture of the same site, I realized what I was doing was almost like rephotography. I decided at some point maybe I should just plot all of the Jencks houses out on a Google map. And then if I’m in the neighborhood, I can go visit them or see what their status is. But the project really started just because I love going on walks, and it also became a reason to go to a new neighborhood.

Revisiting Charles Jencks’ Daydream Houses of Los Angeles illustrated presentation, organized by MAK Center for Art & Architecture and The Southland Institute, June 25, 2019. Image courtesy of The Southland Institute.

I didn’t even really think of it as a project at first, and was not too concerned about what format it might take, though a book could be nice. I was just curious about the original houses and having fun with it–enjoying what you’re doing is so important. I wasn’t really doing it very diligently either and it wasn’t until I got an invitation to do something at the MAK Center, at the Schindler House, through the Southland Institute, that I thought I’d do a presentation about Daydream Houses because what could be a better place or context to do it in? A lot of the Jencks houses are in that West Hollywood neighborhood. That was when I really started to fill in the blanks and I was like, okay, I should try to rephotograph all of Jencks’ daydream houses. I didn’t get to all of them in time for the presentation, but that was okay. I really like the format of a slideshow or a presentation as a way to test new ideas. The Southland Institute likes to provide transcripts of their programs on the website, which I think is very thoughtful, but there was an error and they accidentally didn’t record it.

KW: That’s too bad.

AT: In the presentation I went through Jencks’ book start to finish, with my image and Jencks’ side by side, and with Jencks’ original descriptions. And if I didn’t have a contemporary photograph, I just put a big question mark.

And one thing that was so wonderful is there was audience participation at the talk. There was somebody in the audience who had lived in one of the houses—“Mushroom Overtones” it’s called—or his ex-wife had lived there, or wife, or something. There were a lot of people in the audience who had their own stories and relationships to some of the houses. “Japanese Witch With Plastic Snow Shingle” was one that I hadn’t actually found and someone in the audience knew where it was. And so I’ve since updated my project. But it was just really fun and that’s all I wanted it to be in a lot of ways. I think there is a lot of value to these projects that are just the result of something you really enjoy.

Still from Revisiting Charles Jencks’ Daydream Houses of Los Angeles, 2019 (left: image from Charles Jencks, Daydream Houses of Los Angeles. New York: Rizzoli, 1978; right: Aurora Tang photo). Courtesy of Aurora Tang.

Still from Revisiting Charles Jencks’ Daydream Houses of Los Angeles, 2019 (left: image from Charles Jencks, Daydream Houses of Los Angeles. New York: Rizzoli, 1978; right: Aurora Tang photo). Courtesy of Aurora Tang.

KW: Something that I find very hard in this city is dealing with all the change. A lot of these colorful, strange buildings and smaller houses seem to disappear. I wonder if cataloging is also a way to have agency in that huge, completely powerless state of living in a place where there’s not much that you can control about the built environment except to notice it.

AT: Yeah, definitely. It is one way to make sense of your environment, but you start noticing things—these patterns—and then it’s very hard to stop noticing them. It’s overwhelming, but then obsessively documenting the landscape can create its own overwhelming collection that you have to deal with. Sometimes there is this sense of urgency to capture or photograph something when you see it and I’ve noticed one thing that’s been interesting over the years is also how the castles, for example, they change—they’re leased out to different businesses and sometimes the castle facade goes away, and sometimes it sticks around. I do get sad when they go away completely, but it’s still always the site, and it’s just really interesting to see it all change.

I think a lot about other projects and attempts to catalog the city—Environmental Communications, Jencks, Ed Ruscha—and just how valuable those images end up being in that they’re capturing these everyday aspects of the built environment that are otherwise hard to find. Nowadays, I don’t know what will happen because there are so many images everywhere, of everything. I think the key will then be in how you catalog those or make sense of them and sort them. That’s something on our minds at the Center for Land Use Interpretation, and for me personally, too. But I will say I do have many hard drives, just full of photos, as many people do now.

CLUI photo from the Morgan Cowles Archive. Courtesy of the Center for Land Use Interpretation.