Second Life: Criss Cross Double Cross

by Gabriel Cifarelli

Criss Cross Double Cross, Issue 1 (Fall 1976). To download a PDF excerpt, click here.

Since the early 1970s, artist Paul McCarthy has initiated a number of curatorial projects that, while not belonging to his art practice proper, evoke some of the same over-the-counter immediacy and supermarket sublimity found in his celebrated videos, performances and installations. From a short-lived cable access television program that presented early video art to a little-known magazine called Criss Cross Double Cross, these early projects were motivated by, as McCarthy puts it, “a ‘60s attitude that artists be part of how art is shown as opposed to it being in the hands of non-artists.”1

Conceived of as a space to publish original works by artists, McCarthy published and distributed only one issue of Criss Cross Double Cross on tabloid sized newsprint in the Fall of 1976. Avalanche in New York and Vision out of San Francisco, to name but two of the many artists magazines that McCarthy was familiar with, were already exploring the medium’s potential as a venue for the presentation of art itself; but McCarthy had no interest in forming a rival publication. “It was more related to wanting to figure out a way to present all the artists who were living in Los Angeles at the time,” he explained.2It was also meant as a public forum for a community of artists who were centered on performative and conceptual practices, like McCarthy himself.

He offered a two-page spread to 38 artists who at the time were all living in Los Angeles. Each artist was free, within the confines of the page and expressive capacity of black ink and newsprint, to produce whatever he or she wanted. He was careful not to impose his editorial sensibility on others, explaining that projects of this kind are about “artists taking, in some degree, control of their own work.” Consequently, there was no editorial intervention of any kind, no interviews, no introductions, no reviews, no contextualizing, and no advertisements––just the artworks themselves.

Most of the artists used the space for works that were a continuation of their art practice in general, but a few played with the specificity of site by referencing the conventions of the magazine format: Billy Adler chose to print a massive Copyright “©” so large that that there could be no confusion that his work is, indeed, Copyrighted; Barbara T. Smith provided a deliberately amateurish Vogue-style layout while serving up ambiguous and self-serving fashion advice; and Susan Mogul claimed the back cover with a hilarious pseudo-advertisement for “top designer video art.”3

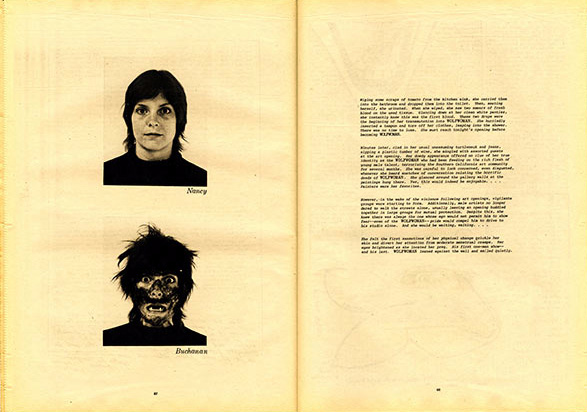

Perhaps the dominating sensibility of the magazine is one of performance artists translating their practice onto the page, typically through documentary photographs and descriptive text. Suzanne Lacy, Allan Kaprow, Ulrike Rosenbach, and Nancy Buchanan’s “becoming WOLFWOMAN” piece among others share this sensibility; in Buchanan’s work, a conventional self-portrait appears alongside one of her as a jagged-teethed, hairy faced, mouth-agape WOLFWOMAN, with a text describing her reign of terror on LA’s male artists. Likewise, some of the works that appeared in Criss Cross Double Cross would move from page to practice, appearing later in other forms and iterations. Martha Rosler, for example, interviewed a couple who lost their daughter to an eating disorder and published the transcript in Criss Cross Double Cross, making it into a video piece the following year.

Almost all of the artists used text, and many—Bruce Nauman, Chris Burden, Cynthia Maughan, Newton and Helen Mayer Harrison, Guy de Cointet—used only text. Nauman contributed a pair of poems that were variations of poems he had used as part of a performance piece several years prior. In the magazine, they lose their performative aspect but gain a Mallarmean sensibility in the way they account for the newsprint page itself, referring even to “small smudges on the tips of my fingers.” David Askevold, a true outsider, was the only artist to render images primarily by hand.

Nancy Buchanan, Wolfwoman, 1976. Image courtesy of Cardwell Jimmerson Contemporary Art.

Criss Cross Double Cross: even the name is like a mini-Language poem that doubles back on itself. Unlike monosyllabic titles like Time and Fortune, the cover gives no clue to the magazine’s content and the fancy cursive curlicues that embelish the title-phrase only add to its ungainliness. And then there is the size: at 11 by 16 inches, it is just a little too large, a magazine designed to protrude from the shelf or coffee table. Criss Cross Double Cross indeed makes its presence felt, not as a magazine to recline with and flip through, but as an object to confront.

For whatever its successes as an art object, Criss Cross Double Cross was a financial misadventure. “It was crazy to do it,” McCarthy admitted. 1500 copies of the first issue were printed, but he could only pay half of the printing bill and wound up with about 700 copies to distribute; the printing company presumably pulped the remainder. Of the copies he did obtain, McCarthy says, “I had no way of knowing how to distribute them, and ended up giving them away.” Since an important goal of the magazine was to find new audiences, this limited distribution was a significant problem. He was personally out of pocket for all the expenses, with only a vague plan to recoup his investment and fund future issues through income from sales. It did not work out that way. Soon after the inaugural issue of Criss Cross Double Cross was released, he abandoned plans for future issues.

Some thirty-five years later, however, its successes as an art project, alternative magazine and curatorial experiment seem undeniable. The DIY ethos of the self-published magazine is also, perhaps, overlooked within the narrative of McCarthy’s own tremendous success with monumental sculpture and elaborate film productions. In our interview, McCarthy explained that, “in some ways I make a clear distinction between that kind of work [such as Criss Cross Double Cross] and my practice; but in other ways they seem to merge together into my activity as an artist.” “How I understand art,” he says, is “that art is a kind of network of artists. I feel strongly about artists creating venues to show work.”

To download a PDF excerpt of Criss Cross Double Cross, click here.