Subcontinental Synth: David Tudor and the First Moog in India

by Alexander Keefe

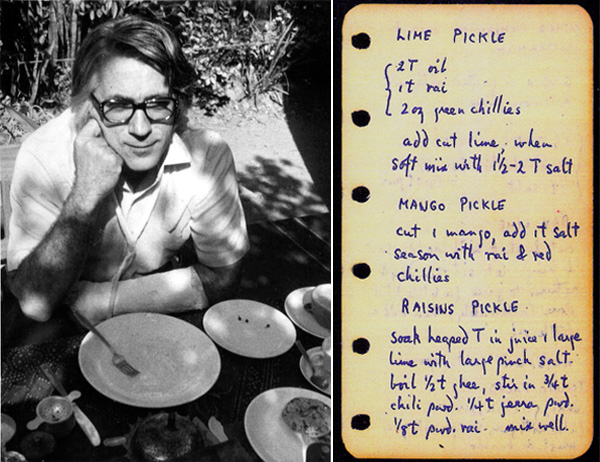

Left: David Tudor, ca. 1974. Photo: Vikas Satwalekar. Right: Handwritten recipes from Tudor’s cookbook. David Tudor Papers, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (980039). Courtesy of the David Tudor Trust on behalf of the Estate of David Tudor.

By all accounts David Tudor was a superb Indian cook. He was other things, too. Widely considered to be the finest performer of the increasingly demanding new piano music of the midcentury, Tudor, who died in 1996 at the age of 70, maintained a busy touring schedule as the accompanist for Merce Cunningham’s dance company for more than 40 years. From the early 1950s on, he was John Cage’s closest collaborator and premiered many of the composer’s most important works, including the (in)famous 4’33”. He was in constant demand in the fifties and sixties for performances of contemporary works for piano, with ardent admirers, including Morton Feldman, LaMonte Young, Earle Brown, Christian Wolff, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Pierre Boulez; and in the late sixties, to Cage’s dismay, he moved away from performing the works of others and became a pioneering composer of live electronic music in his own right—a shift signaled by his visionary Bandoneon! (a combine), a complex early cybernetic environment that “composed itself” using inputs from the eponymous accordion-like instrument, which Tudor used to activate a system of sound, light, video, and mobile sculptural loudspeakers.1 But throughout his adult life he was also a damn good Indian cook and liked nothing more than spending days on end preparing elaborate meals for his friends.

A visit to Tudor’s small and sparsely furnished century-old farmhouse at the Gate Hill cooperative in Stony Point, New York, was like a visit to an alchemist’s laboratory. Friends describe a spice rack of Byzantine complexity, jars of alcohol in various states of infusion, microphones wired to the trees outside, and electronics within. The care he took with his Indian cooking, in particular, is manifestly evident in a handwritten cookbook, now archived at the Getty Research Institute [GRI] in Los Angeles, containing hundreds of authentic South Asian recipes, copied by hand in one sitting and with ingredients given by their Hindi names.

That his connection to the subcontinent went beyond the gastronomic level is well documented in the David Tudor correspondence archived at the GRI, where there is a whole folder devoted to a family in the Indian city of Ahmedabad: the Sarabhais.

Le Corbusier, Villa de Madame Manorama Sarabhai, Ahmedabad, 1951. Photo: Nicholas Iyadurai. ©FLC/ARS, 2013.

1. An Indian Attachment

Dear David,

Why so silent! We think of you and John so often that I felt I must write to you…

Letter from Manorama Sarabhai to David Tudor, February 11, 19592

My dear David,

Your silence for so long is painful—and ununderstandable. I at least expected a letter from Delhi or from the way— But in life one finds that one never can get expectations—still I felt that I should write to you and express what I feel. I will not write more before I hear from you—because there is no point. Lack of communication so complete as this from friends does warrant an explanation.

Letter from Manorama Sarabhai to David Tudor, March 4, 1963

Dear David,

I have heard from Gira that you may be coming to the Design Institute some time this year. May I ask you to be my guest for the duration of the time that you will be in India. It would be such a wonderful thing. At least write some lines and let me know when you will be coming.

Letter from Manorama Sarabhai to David Tudor, March 1, 1969

The very first document that came to my hand, a Christmas card from the early seventies sent by Anand Sarabhai and his then-partner Hildegard Lamfrom, evokes Tudor’s passion for Indian cooking and is printed with “sample recipes from Gujarat state to be improved upon by David Tudor.” On the bottom it says, “Come visit us in Ahmedabad for other delicacies.”3

Tudor had been visiting the western Indian city of Ahmedabad since the early sixties and had a standing invitation at the Villa de Madame Manorama Sarabhai, designed by Le Corbusier in 1951 and named for its owner, Anand’s mother.4 Manorama, whose first letter to Tudor is postmarked London, 1959—they may well have met there—was the widowed daughter-in-law of Ambalal Sarabhai, the patriarch of an industrialist family in western India comparable in stature with the Rockefellers.5 The Sarabhai family was known for its wealth, its long association with Indian independence leaders, and its patronage of the arts. Manorama, who was herself from an important mill-owning family in Ahmedabad—her brother Chinubhai Chimanlal was the mayor of the city and largely responsible for Le Corbusier’s projects there—used her considerable wealth to commission works and frequently long visits from international artists, including Isamu Noguchi, Le Corbusier, and Alexander Calder, beginning in the mid-1950s.6

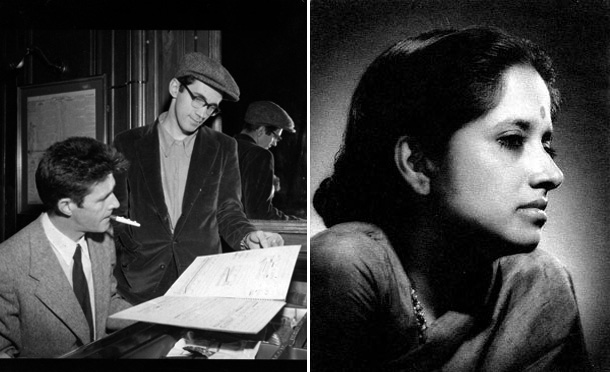

Left: John Cage and David Tudor, 1954. Courtesy of the New York Public Library. Right: Geeta Sarabhai Mayor, Baroda, 1951.

But it was Manorama’s sister-in-law Geeta Sarabhai (later Geeta Sarabhai Mayor) who was initially responsible for bringing New York to Ahmedabad. She met the impecunious and still largely unknown John Cage in 1946 in New York, at a peculiarly low ebb in the composer’s personal and professional lives.7 Geeta had come to the US as a music student, concerned about the effect of Western musical modernity on Indian classical traditions. Introduced by their mutual friend, Noguchi, she and Cage agreed upon an educational exchange: He would teach her the rudiments of Western musical theory, including 12-tone serialism; she, in turn, would introduce him to Indian classical music and philosophy. The proximate result of their almost daily interaction over the next six months—often in the company of young composer Lou Harrison, shortly before his groundbreaking introduction of Javanese gamelan percussion instruments into contemporary music—was Cage’s pre-Zen immersion in South Asian philosophy and aesthetics.8 His partner and muse, Merce Cunningham, followed suit in his own choreography and, by the time she left town later that year, Cage and Cunningham had found in ‘Geetaben’ and the Sarabhai family a singular set of patrons in a faraway and unlikely place. Invitations to perform in India soon followed, but it wasn’t until 1964 that Tudor accompanied Cage, Rauschenberg, and the Cunningham Dance Company on an international tour with four stops in India: Bombay, Chandigarh (because the Sarabhais thought the Americans would like to see the Corbusier-designed city), New Delhi, and Ahmedabad.9

A city known in India for its long history of mercantilism and industry, as well as its connection with Mohandas Gandhi—whose ashram on the banks of the Sabarmati River, built there in 1917 with funding and encouragement from the Sarabhais, is a critical landmark in the story of India’s independence—Ahmedabad soon became a kind of outpost of the New York downtown scene. As a result, this distinctive and in many ways idiosyncratic industrial city in western India played an outsize role in presenting and representing the rather more nebulous notion of “India” to artists and musicians whose influence on the American and international scenes can hardly be overstated.10

Over the next decade, the ties between the Sarabhai family and these luminaries of the American postwar avant-garde grew closer, and members of the family, particularly the widowed Manorama, played host to many of them.11

2. Designing India

Ahmedabad, a city of around five and a half million people some 300 miles north of Mumbai, is dusty, polluted, and has a disturbing recent history of communal violence, rioting, even genocide.12 But entering the leafy compound of its elite National Institute of Design (NID) feels like entering another world. It sits in something like a modernist walled garden, located on the banks of the Sabarmati River across—and at a safe remove—from the labyrinthine old city.

It was established in 1961 with the financial backing of the Ford Foundation and the political backing of the government of India, with Manorama’s brother-in-law Gautam Sarabhai as its first chairman. In early 1962, they got to work putting it together, with just one faculty member—Dashrath Patel—and a temporary headquarters in the Sanskar Kendra, an almost-finished museum building designed by Le Corbusier in 1951, located just across the road from NID’s current campus and now gone very much to seed.

Sanskar Kendra Museum, Ahmedabad, India. Designed by Le Corbusier in 1951. Photographer unknown.

The pedagogical program for NID was supposed to fall somewhere between Montessori and the Bauhaus. Preliminary reports commissioned by the Ford Foundation had emphasized the importance of workshop-based education and a student-teacher ratio of one to one.15 Gautam and Gira Sarabhai drew from their experiences abroad, as well as their own Montessori training, to flesh out the initial project idea, replacing exams with continuous feedback and periodic evaluations, recasting the role of teacher from stern authority to guide and facilitator, and eschewing rote, passive learning for project-based “learning by doing.” Even now, the idea seems progressive; in an India still enduring the long hangover from the British colonial education system, it was downright revolutionary, if not utopian. Perhaps this is why, from the start, they felt the need for a heavy infusion of foreign expertise: Invite the best for short stays, the thinking went, rather than the mediocre for long.

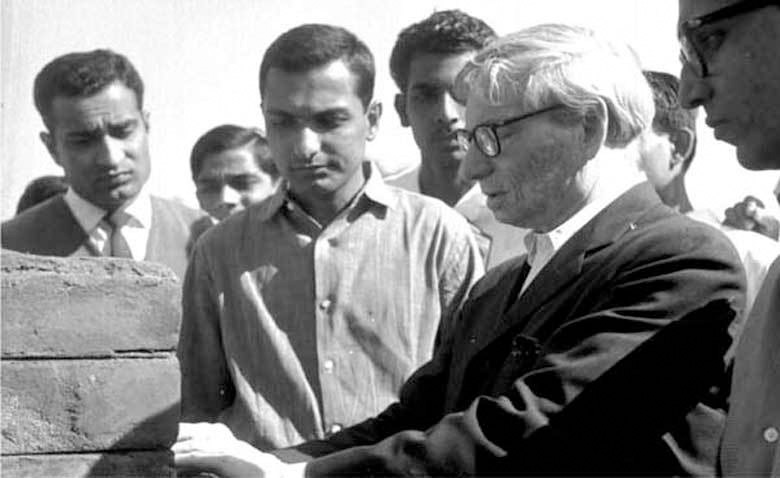

Louis Kahn seen with NID architects including Sen Kapadia and BV Doshi, ca. 1960s. National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad.

With that dictum in mind, the NID hosted a stream of distinguished visitors between 1962 and 1971, all funded by the Ford Foundation. Foreign exchange in India at that time was scarce and typically accompanied by mountains of red tape, but the Ford Foundation’s dollars enabled the NID to bring in speakers, faculty, and equipment from abroad.16 The institute’s Indian and foreign faculty were joined for short stints by Louis Kahn, Claude Stoller, Charles and Ray Eames, Frei Otto and Henri Cartier-Bresson, among many others; special lectures included talks by Rauschenberg, Cage, Buckminster Fuller, Maxwell Fry, Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton, Stella Kramrisch and Experiments in Art and Technology [E.A.T.] impresario Billy Klüver, the Monaco-born Swede and one-time Bell Labs engineer who was then busily guiding the group’s prodigious efforts to design and erect the Pepsi Pavilion for Osaka’s world expo in 1970.

In late 1969, Klüver proposed that the NID and E.A.T. join forces in a far-ranging collaboration between the organizations that would bring artists and engineers to Ahmedabad for extended stays. NID’s director demurred on the grand plan but settled for something smaller: E.A.T. would help in procuring and assessing foreign technical equipment, and the institute would host visiting engineers and artists from E.A.T.’s pavilion team in Japan.17 It was through this arrangement that the nation’s first Moog modular synthesizer arrived on Indian shores in 1969, in bulky wooden boxes shipped from Trumansburg, New York, and was installed at the National Institute of Design by David Tudor.

3. David Tudor vs. the Moog

Resonance is the condition whereby a tiny input autonomously cascades into a much larger output. It occurs when a small vibration interacts with the internal structure of a material and greatly increases in intensity, threatening to destroy the object if pushed beyond a certain limit. Chaos is the point at which order breaks down, when elements in an organized system start acting randomly and autonomously, creating a situation where it is impossible to predict exactly what will happen next or in what order. Both involve limits and thresholds that have been crossed, organization that breaks down, actions that go out of control, systems that collapse—creating something new and unexpected in the process.

Bill Viola, “David Tudor: The Delicate Art of Falling,” 200418

And now that I am brimming with

The silence of the Lord,

I have ceased to be sword-maker

And have learned to be the sword.

Harindranath Chattopadhyay, The Divine Vagabond, 195019

At the heart of the story of India’s first electronic music studio—and its primordial Moog—is a set of fractures and contradictions. For one, Tudor himself despised the Moog system and all that it represented, an antipathy that several people I interviewed told me extended to its inventor, Robert Moog himself.20 In 1969, Tudor was focused on preparations for E.A.T.’s Osaka pavilion, which involved collecting and assembling a library of thousands of recordings of natural sounds: birdsong, street noises, insects, whales, animals. Beneath the pavilion’s 90-foot mirror dome was a sound system of astonishing, custom-built complexity designed by Tudor and Gordon Mumma.21 With eight separate but identical processors and a “spatialization matrix” of 37 speakers, the system allowed visitors to wander to different areas of the floor and experience unique, fluxing sonic signatures. The pavilion work was essentially exploratory, open, and extroverted—something that Tudor saw in stark contrast to the control fetish that characterized the Moog synthesizer. His focus was on the intersection of structure and indeterminacy, on unpredictable transformations of unpredictable sounds; these were sounds left, as he put it, “free to be themselves.”22

For Tudor, who was a committed albeit reticent follower of Rudolf Steiner and anthroposophy, this orientation was as much spiritual as it was compositional.23 He was the master, Mumma once said, of “resonance” and “chaos.” The Moog and other commercial synthesizers, as he saw it, were tools that led in precisely the opposite direction, toward ever greater degrees of anechoic determinism, control, and introversion.

But he agreed to bring one anyway, persuaded, perhaps, by the Sarabhais’ patronage and E.A.T.’s role in helping the NID to acquire the equipment.

During this 1969 visit to Ahmedabad, Tudor stayed at the villa with Manorama, conducted workshops on live electronic music, and set up NID’s sound studio with the Moog equipment—among them a Bode Frequency Shifter Model 6552 (#1003) and a Dual Ring Modulator Model 6402 (#1113)—two Ampex AG-350-2 2-channel tape machines (made in Britain for the UK and European markets), a Quad stereo preamplifier and two separate Quad power amplifiers, Tannoy monitor loudspeakers, a Moog mixer with line and microphone inputs, and at least three Sennheiser MD 421 dynamic microphones.

He also prepared a sound installation consisting of what he later called “incidental music” for an “exhibition and fair” at NID, at the behest of Cage’s old friend Geeta Sarabhai.24

And after that the Moog, with very few exceptions, just sat there.

That this was so should have been evident to me when I first heard about it, from long-time NID faculty member M.P. Ranjan, who was a grad student in furniture design at the time of Tudor’s 1969 visit. Ranjan mentioned in passing that a friend of his at NID had rescued the first Moog from the trash heap—so to speak—a number of years ago. The Ford Foundation money had bought some nice equipment, but a lot of it never saw much use. Ranjan once showed me a locked shed on campus that was piled with the stuff. Replacement parts for something like a Moog, or early videotape recorders and cameras, even film projectors, were prohibitively expensive and their use by students was carefully limited and controlled. The music studio had been one expensive idea—one among many—that never really went anywhere.

But it was also symptomatic of a larger malaise setting in around the institute at the close of the 1960s: The heady dawn of NID’s pedagogical program, its foreign visitors and emphasis on collaborative learning, had created an institution that was largely illegible to Indian government types, generating suspicion and criticism of the Sarabhai family’s administration. At about the same time that David Tudor brought the Moog and set up the experimental music studio, NID was fast approaching a major crisis, losing foreign funding and coming under the wary scrutiny of important officials in the Indian government. The Ford Foundation wasn’t happy and neither, at least according to Billy Klüver, was Porter McCray, who was the force behind the John D. Rockefeller III Fund’s Asian Cultural Program at the time.25

In October of 1970, hoping to improve the school’s all-important relations with New Delhi and its bureaucratic purse strings, Gautam and Gira Sarabhai appointed a retired admiral named Soman to the newly created post of executive director.

From the beginning there were tensions between the Sarabhais—hitherto unquestioned in their authority—and Vice Admiral Soman, a man with a passion for calisthenics and little taste for art and design. When they fired him in 1972, Soman went public with his grievances and sensationalized accounts began to appear in India’s newspapers, with hints of financial impropriety directed at the Sarabhai siblings. Criticism was leveled at the experimental nature of the school’s pedagogy and its apparent disconnect from the outside world. An especially sore point was the accusation that, despite NID’s status as a national institution, it was essentially being run as a private enterprise by and for the Sarabhais.

Things gathered enough steam that not one but two committees were appointed by the government to look into the matter, with mixed findings: The Sarabhais were absolved of personal culpability, but the institution was found to be “lacking of purpose.” In 1973, Gautam resigned, and Gira followed. In September of that year, the river rose some 26 feet and flooded the ground floor of the NID buildings to 8 feet. The early days of NID were officially over, and with them, the collaborations with E.A.T., the invitations to the likes of David Tudor and John Cage, and in some ways the experiment itself. The NID gradually transformed itself into a more professional and conventional design school, an incubator for generations of legendary Indian ad men, visual artists, and product designers.

4. The music of changes

When I came to the Cage I had to work on the moment-to-moment differences. Music of Changes was a great discipline, because you can’t do it unless you’re ready for anything at each instant. You can’t carry over any emotional impediments, though at the same time you have to be ready to accept them each instant, as they arise. Being an instrumentalist carries with it the job of making certain physical preparations for the next instant, so I had to learn to put myself in the right frame of mind. I had to learn how to be able to cancel my consciousness of any previous moment, in order to be able to produce the next one. What this did for me was to bring about freedom…

David Tudor, from an interview with Victor Schonfeld in August 1972

Birthday comes every year, but to have you here with me is rare. My heart is full of images yours—what can I say in words! Or give! In a sense I have mentally given you all I have. I wonder what there is next! Many people, including me, must have told you “they love you.” I was thinking about it. If I feel the oneness with you as I do and do not feel the duality it would be like saying “I love myself.” So I hesitate to use the conventional words. Can oneness be expressed in words.

Letter from Manorama Sarabhai to David Tudor on his 48th birthday, January 20, 1974

Julie Martin, who was Billy Klüver’s assistant at E.A.T. and later his wife, remembers a story about Tudor’s last trip to India, in 1974. When he was at the airport on his way out of the country, the immigration official asked him, “When will you be returning to India?” As Tudor recounted it to friends, his response was, “Not in this lifetime!” Indeed, the correspondence from Manorama, who died in 1993, slowed to a trickle following her most confessional letters in the mid-1970s after this final visit.

It is hard enough to reconstruct the feelings and inner worlds of the most public, demonstrative people; for one as reserved as Tudor, it is damn near impossible. He was an eccentric, intensely private, even secretive man; close friends report that he never, or very rarely, discussed anything outside of his work: not his lifelong relationship with ceramist and writer M.C. Richards, which began when they met at Black Mountain College in the summer of 1951; not his deep interest in the spiritual and esoteric, especially the occult ideas of Rudolf Steiner; not the vicissitudes of his sometimes tempestuous relationships with Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen; not his family. His letters, if any were written in response to Manorama, are lost, or perhaps hidden in a desk somewhere in her villa. But what remains are two odd sticking points, flotsam cast off and left afloat in the wake of a peripatetic life: a set of ant-infested, first-generation Moog modular synth equipment gathering dust in Ahmedabad and a handwritten book of Indian recipes in his papers in Los Angeles.

Tudor’s Moog, photographed in Ahmedabad ca. 2012. Courtesy of Dhun Kakaria.

He traveled at times incessantly and ate in restaurants and homes from Osaka to Oslo, but when he got back to Stony Point it was Indian food that he craved. Tudor, in his way, was an Indophile, but he loved India more in theory than in practice: Like so many of his peers, including Cage and Cunningham, and even committed neo-sadhus like Terry Riley and LaMonte Young, he preferred his garam masala to be mixed and served at home. His private Indian cookbook is at once a disciplined homage to India, a love letter to Indian cuisine, and an ingenious way to avoid ever having to return there. But if Tudor’s affection for India was distanced, India―Ahmedabad, really―loved him back unreservedly: “You are one of us,” Manorama wrote him after his last visit in 1974, “and everyone loves you.”