Suzanne Lacy on the Feminist Program at Fresno State and CalArts

by Moira Roth

This is an edited transcript of an oral history interview with Suzanne Lacy, conducted by Moira Roth in Berkeley, California, March 16, 1990. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

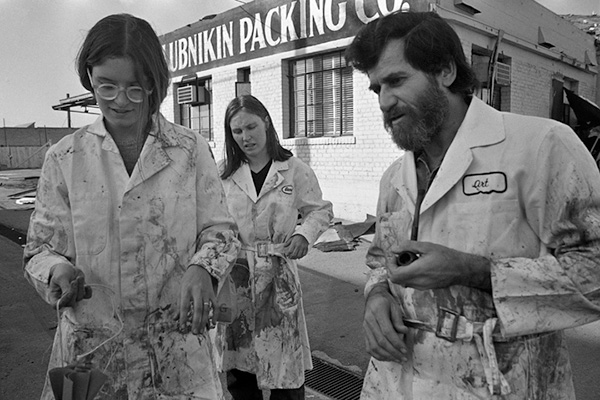

CalArts students at Klubnikin Packing Co., downtown Los Angeles, in Maps, 1973. Happening in Los Angeles, CA. Photo: Susan Mogul. Courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.

In this interview Suzanne Lacy offers a thorough discussion of the development of feminism in California and the California art world in the early 1970s. She describes her introduction to Judy Chicago and her subsequent involvement in the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State and later at CalArts. She describes the development of her own performance-based work and discusses the influence of other artists such as Faith Wilding and Allan Kaprow.

SUZANNE LACY: I discovered feminism in ’69. I then applied to graduate school at Fresno State and—

MOIRA ROTH: Why did you single out Fresno State?

MR: [Laughs]

MR: Could you describe the program at Fresno that Judy Chicago ran? Who was in it, how she conducted it, how you felt about it.

SL: Well, once I got in, I was very excited. I was a second-year grad student in psychology at the time, and I was moving so far out of academic psychology by then that I was working in sociology and race relations and things like that. I think one of the major things I got out of it was my first real encounter with female sensibility. I had always had women friends, but I had been trained academically with men, had identified with them, and had found some things about women quite provoking. Mostly, their lack of freedom and inability to experiment, go places, and do things (which I thought was what men did). But when I got involved with that program, for the first time I began to appreciate not just particular women but all women.

In terms of the structure, Judy brought about fifteen students together. We had to make a major commitment of time and money. That is, we could take anywhere between three and twelve units of school credit. For many of us, over 50 percent of our schooling was this program. The first thing she did was ask us to buy work boots. Then she taught us how to deal with realtors, as we canvassed Fresno to look for an abandoned space to make into our studio. We found this huge old theater outside of town and, with our work boots, began to transform it. Judy taught us carpentry. I was certainly familiar with tools and stuff, but I’d never learned how to Sheetrock. We made flawless walls. We completely renovated this whole place. And in order to do that, we had to pay money; I think at that time it was $25 a month, which was a rather major commitment. I was freaked out, as I’ve always been since I’ve been an artist, about money. But nevertheless, we all did it to support the rent and utilities in our studio. We had a series of courses. We had reading studies, feminist art history, and studio art. That’s when we first started discovering people like Frida Kahlo, Mary Cassatt, and other women artists who were uncovered subsequently or simultaneously—I’m not sure which—by art historians. Several women we discovered by rooting through used bookstores. I remember when Nancy Youdelman came to class one time with the book of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and the first Women’s Building. This was revolutionary to us. We poured over this and other books and found photographs in esoteric places.

Students of the Feminist art program at California State University, Fresno (1970-71).

Ti-Grace Atkinson came to Fresno, and we prepared a cheerleading reception for her. We went down to the Fresno airport prepared to do our “c-u-n-t” cheers—with the pink cheerleaders—and off came 40 or so Shriners as we were screaming, “Give us a c, give us a u.” [laughs] Right behind them came this giant leggy woman wearing sunglasses at six o’clock at night and carrying a cigarette holder. She had buckskin pants and a giant fur coat. That was Ti-Grace Atkinson, who sat there sort of bemused while we were performing madly for her. It was quite an evening. Judy and she had a real run-in. The gist of it was Ti-Grace felt that everybody, male or female, who had anything to do with patriarchy was completely screwed, and Judy’s position was to work with the men in your life.

MR: And you named your dog Ti-Grace.

SL: Yes. I had a dog named Ti-Grace, a dog named Simone—after Simone de Beauvoir—and a cat named Red Emma [after Emma Goldman]. They were fixtures of the early feminist movement. You’ll find their photographs in a variety of places, documenting the building of the Woman’s Building. The dogs, I mean, not de Beauvoir and Atkinson. So we built ourselves an art studio, and we spent a lot of time working on our art. Judy would give us assignments having to do with topics, for example, like rage. You know, like, “How do you feel when you’re walking down the street with men leering at you?” There was indeed a lot of anger that got expressed in those early performances. People turned to performance almost intuitively. It wasn’t as “sophisticated” as some of the Conceptual performance works at the time. For the most part, we didn’t know anything about that work, and I don’t think Judy knew a lot about it either. We were doing what I’d call skits. She intentionally steered us away from anything that was Conceptual, that was removed from a direct engagement with our feelings. We made art of our experience. I remember I put up huge pieces of paper on the wall, 8 feet by 6 feet, and I’d throw balloons full of paint at it, and slosh paint around. We were very physically engaged. As well, we had crits and we had consciousness-raising sessions.

SL: There were aesthetic judgments, but it was based on the ability of the work to authentically reveal the self and one’s feeling states. It was probably not divorced, in some respects, from Abstract Expressionism, although the work was not abstract. Judy gave assignments having to do with emotional states or feelings about mothers or about other women. Of course, one could also just do art art. There was no prescription against that. But we were very caught up in a burgeoning awareness of what it meant to be a woman.

Those first consciousness-raising groups were incredibly intense. It was like uncovering, in a funny way, an entire new world within your self. I remember seeing the movie The Bell Jar, from the book by Sylvia Plath, and watching the scene where she’s almost raped by her date, and thinking, My God. While I have never been raped, I had certainly had rather forceful experiences with dates. The kind of pressure that you wouldn’t ever describe as attempted rape in the fifties and sixties. So our work together was like a continuing revelation. I did paintings, not much performance at that point. I did a lot of conceptual work, wrote, and I made sculptures. I guess one sculpture that stands out in mind is a life-size bride, which ended up looking like a cadaver, that was made with resin.

It looked like a macabre Kienholz, with birth control pills for her bridal bouquet and a gag over her mouth, and she was lying in a position like she was about to be raped. It was a papier-mâché figure with about an inch of resin meticulously layered, and then this cloth wedding gown that was also layered in resin. The whole thing had this rigid fifties look. And her eyes were popping out of their sockets. For a cunt she had a plunger with a pink lightbulb in it. I didn’t realize it at the time, but it was an aggressive and frightening image of marriage as a trap. Lord knows where that came from. Needless to say, however, I’ve never gotten married. [laughs]

MR: How did you and Judy relate to one another?

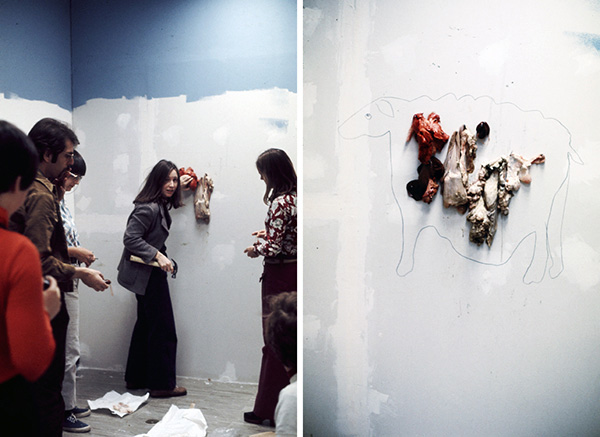

Suzanne Lacy, Maps, 1973. Happening at CalArts, Valencia, CA. Pictured, Left: Bia Lowe, Stanley Fried, Susan Mogul, Vanalyne Green and an unidentified student; Right, Detail of Maps. Photos: Suzanne Lacy. Courtesy of the artist.

Later, when the group was getting ready to leave for CalArts, a similar rapid transformation happened. Judy and Miriam Schapiro were going to do a feminist art program at CalArts, and everybody was preparing to go there and trying to get in, and I wasn’t because I was a second-year grad student in psychology, on my way to getting a master’s. One day, Faith Wilding said to me, “Have you thought about coming to CalArts?” and I said, “Well, no. Not really.” That night I just stayed awake for hours in a fever, tossing and turning, and the next morning I got up and immediately went to the phone. I called CalArts to apply for a scholarship—because I didn’t have any money at all. At that precise moment, Judy broke into the line. This was before call-waiting. Judy’s method of getting through to you was through emergency interrupt. At that moment, just when I was talking to CalArts, I get this emergency interrupt from Judy, who says, “Suzanne-y, I’ve been thinking. Maybe you should apply to go to CalArts. Have you thought about that?” And so I went to CalArts.

MR: Hmm!

SL: We were really gutsy. I mean, we were really presenting a very tough female image—to the world through our art and our panels. Because of Judy’s connections, we were able to make presentations in Los Angeles, the art world, and at schools. There was one weekend when Larry Bell came, and Miriam Schapiro and Sheila de Bretteville—Vickie Hall did a performance there. She was a terrific performance artist who moved to Fresno to study with Judy. A lot of people from CalArts came down, and we would have these big powwows, art showings, slumber parties. They were very exciting and intense times. That’s when I met Sheila, who decided, prompted by Miriam and Judy, to do a feminist design program at CalArts.

MR: Did you also witness the beginning of Miriam and Judy talking with one another?

MR: [Laughs]

SL: I said, “What is that, Arlene?” Judy went into a fit about it, because in her mind Conceptual artists were people like John Baldessari—distanced, aloof, abstract. In fact, that is part of conceptualism, but nobody had at that time managed to integrate a feminist emotive consciousness into that form of art, which they subsequently did.

MR: And then, when you did finally decide to go to CalArts, how were you integrated within the programs?

SL: Personally, or how were the feminist programs integrated into CalArts?

MR: Well, both, I guess, because you were also working for Sheila de Bretteville.

SL: The feminist programs at CalArts were several. Miriam and Judy did the Feminist Art Program. Sheila did the Feminist Design Program. Deena Metzger did Women in Literature and Women’s Writing. In the social sciences program—I think it’s called humanities at CalArts—there was also a group of women working on women in sociology. At this point in time (1970, I think), there was a massive amount of feminist consciousness and activity there.

MR: And CalArts had begun of couple of what? A year or so before? It was a hot spot.

SL: CalArts had begun a year before at a temporary campus in Glendale, where such things as nudity in the swimming pool took place, and Alison Knowles’s flying helicopters distributed paper for an event and Ravi Shankar played in the halls.

MR: Yeah.

SL: Gene Youngblood was there, and Allan Kaprow—there was an amazing amassing of talent that happened in the early days at CalArts. And while that was Disney’s vision, it was Paul Brach’s doing, at least in the visual arts. He was head of the art department. But the Disney family was not Walt Disney, and it took them a while to figure out what they had done. Much more conservative, they tried to whip the school into shape. They moved to the new campus at Valencia. I had already made a liaison with Sheila, who liked my rationality—

MR: [Laughs]

Allan Kaprow (right), Bia Lowe and an unidentified student, in Maps, 1973. Photo: Susan Mogul. Courtesy of Suzanne Lacy.

The second year at CalArts is when I began to establish my interest in performance, and I worked with Allan Kaprow. I think Allan and Sheila and Judy formed three kinds of very important influences, with Arlene Raven and Deena Metzger being other influences. But the three of them, theoretically, the way they thought, was so different, and yet I managed to merge some of their forms of thinking and take what I needed from each of them. They gave me a very strong base for exiting from CalArts.

MR: What did you draw from Allan Kaprow?

SL: Well, first an incredible legacy of events, happenings, Conceptual work. He had collected an array of books at the CalArts library. Michael Kirby and Richard Schechner and fluxus history. Allan’s formalism was supportive to my own inclinations in that direction. I know it’s hard to see the formalism, because people aren’t used to assessing the formal aspects of time-based work. I’m concerned with the structures and shapes of things. I like very controlled works. Because he was working so closely with many of us feminists, Allan’s work gave us a foundation for the move into “life” that we were looking for in a political sense. He gave us a rationale for it. I thought of them, humorously, as Judy the passionate mother and Allan the affectionate, distant father.

Because Judy was all content. Obviously Judy is herself a strong visual formalist, but her teaching was for expression, expression, expression, whereas Allan’s teaching methodology was cool, discursive, anything was possible, everything was interesting to discuss. And Allan also was at a very interesting point in his career. I learned from that—quite a bit. We knew him as the founder of Happenings, the Abstract Expressionist of the time-based media, a very major figure who had suddenly dropped into obscurity. I think he was struggling with how to handle not only the move to the West Coast but the move from the grand, expressive gesture to a different kind of concern. He was just beginning to have a shape for those concerns then. So I watched him work with his body, work with his pulse. He’d spit on his hand and note how fast it dried. He’d put us through all these paces, too—just like we put him through paces in our pieces. I remember having a revelation one day. We were sitting in a group when Allan casually mentioned how when he was a child, he was so intensely allergic that even to this day, if he eats a nut, his whole body literally blows up. And I sat there thinking, My God, that’s what’s going on. This man has this relationship to his body that’s at once kind of quizzical and distanced and yet threatening, tragic. I could empathize with these incessant experimentations trying to uncover the range of unconsciousness that happens within the seemingly simple gesture—the sociology of the unspoken. It took him a while to find a form for that.

MR: Did you also have contact with people outside CalArts, such as Barbara Smith, Rachel Rosenthal, Nancy Buchanan—

SL: No, none of those people.

MR: —Eleanor Antin—

SL: Well, Ellie did a lecture for Baldessari. CalArts had a very active visiting-artists program, so I got to know who was who in the Conceptual world. But, no, Barbara Smith was probably just getting out of Irvine about that time, and Nancy as well, and so their activity was neither considered feminist—by them—nor reaching other than a regional audience south of Los Angeles. But we did in fact have contact with national feminist artists, because we had the East-West Bag conference at CalArts. A woman was raped on campus, and so that became a focus point; we had a panel discussion with the feminist Z Budapest. Judy kept us connected with the Los Angeles, even national, feminist art scene. Womanhouse was the production of the art program. I was in design program, so I did not participate directly in Womanhouse. Judy did a performance workshop, and I took that, along with other classes she taught.

MR: What kind of assignments did she give?

Suzanne Lacy, Cinderella in a Dragster, 1976, on the cover of High Performance, Vol. 1, Issue 1, (1978). Courtesy of Linda Frye Burnham, Suzanne Lacy and Susan Mogul.

SL: One that I remember with fondness was “Route 126.” We had to drive along this two-hour stretch of road between CalArts and the coast and at some point stop the caravan of cars and get out and do a performance that had to somehow be identifiable as done by a woman. That was the only guideline. So we stopped at a telephone pole, and Judy and Shawnee Wollenman tacked Kotex on the pole. We have pictures of them being chased away by the highway patrol, who made us take them down. Nancy Youdelman did this lovely piece at the beach where she draped herself in flowing scarves like Isadora Duncan and walked into the water until she disappeared. This old, abandoned jalopy in a wash had fascinated me, and I stopped the caravan there for my piece. I gave everybody pink paint, red velvet, and a big stuffed heart, and we transformed this old jalopy into a woman-renovated car, and then we left it. After years there, it was subsequently hauled away within a week.

I had been nailing beef kidneys into the wall every chance I got. Almost got thrown out of CalArts for doing it one time, actually. I conned Paul Brach into giving me a space in the graduate studios and— Did I ever tell you this?

MR: Hm-mm.

SL: It was about half as big as this room, somebody’s studio. I layered plastic and beef kidneys and then strung cord through the whole thing. So if you went in, there was an experience of being inside a body cavity. I was to leave it up for three days, and I came back the second day, and there was Stephan von Huene, the big, tall sculptor, who taught there. He and this host of graduate students lined up behind him, had an aerosol spray that they were spraying in the air. [laughs] They were out to get Paul to throw me out of school. I wasn’t even a painting student. I think it had to come down early. All my beef kidneys were constantly getting cut down. I did one show at Womanspace. I thought it was quite elegant. It was four beef kidneys hanging with a string net, fence, in front of them. It looked Gestapo-esque. I would change the kidneys every couple days so they would stay fresh. I came in one night, and there had been a feminist meeting, and somebody had cut them down. Their four little strings were limply hanging there. [laughs]

MR: Could you talk about Ablutions? Because that was where you appeared fully formed as a performance artist.

SL: That was in ’72, so I believe it was in the same semester I was graduating. Judy never let us rest in terms of reaching audiences. In fact, we didn’t show at CalArts itself. We showed in classes to prepare the work, and then we were out there some place in LA, some school or a gallery. She wanted us to put it out. For some reason, I was always very conscious of violence—I believe it has to do with my relationship to being in a body and with understanding sexual violence as an invasion of the body as a sacred space. At Fresno I said to Judy, “Wouldn’t it be interesting if we tape-recorded stories of women talking about having been raped?” I imagined the audience would sit in a dark room, and we would play the stories for them. That’s not particularly interesting now, but you have to remember that in 1970 you could not find stories of women who were raped. They wouldn’t tell you. So Judy said, “That’s a very interesting idea. Why don’t we start collecting stories.” So Judy and I spent the next year tape-recording. We’d hear rumors about a woman who was raped, and we’d find her friend, and we’d— You know, it was literally having to go down dark streets and end up in strange places in the middle of the night, tape-recording these stories. Some women had never told anyone. We used seven women’s stories. Out of the performance workshop came many beautiful images. Sandra Orgel came in one day and showed us pictures of taking a bath in eggs. The slides showed the parts of her body—her breasts and her vagina—covered with these eggs with menstrual blood kind of running through them. It was a very beautiful image.

So we took these images and the tape recordings, and we put them together in a piece that was a linear narrative. The soundtrack was exclusively the women talking; really straightforward like, “I was walking down the street. I was pushing my child in a stroller.…” Just telling in great detail the whole story of the rape. We had three galvanized metal tubs and piles of kidneys and piles of rope, and Jan Lester and I in white T-shirts and Levi’s and white gloves came out and methodically pounded these beef kidneys in a row, starting from one side of the room to the other. In the meantime, a nude woman came out and took a bath, first in eggs, then in blood, then in clay. She got out, was wrapped in white, laid down on the ground, and then another woman did it. I think two women went through the ablutions. Two other women did some imagery where they were twinning. They were adorning each other’s hair with chains. This was very methodical and throughout women were talking about being raped on a sound system. At the end, Jan and I, like giant spiders, tied everything to everything: the beef kidneys to the people, to the trays, to the—and then we left the scene.

MR: This is when the two women who’d been nude were bound.

SL: Yeah. They were wrapped in white and bound. They weren’t bound really; they were wrapped in white and laid down, and then they were tied to everything. We went over the set, tying it together. And the last words on the soundtrack were, “I felt so helpless. All I could do was just lie there. All I could do was just lie there,” and the tape stuck on that ending. The audience was stunned. They were really stunned. It was in Laddie Dill’s studio, and so there was a fairly heavy-duty Venice art audience there. Apparently, several people just sort of gagged and ran for the door at the end of it. They had never been exposed—not only with that information at that level of detail, but to women’s perspective on it. And the rage and the intensity of victimization that was in the piece. In fact, a couple of the women who were in the piece, one of them had an emotional reaction to allowing herself to participate from the vantage point of the victim. She was one who took the baths. We did it just before we graduated from CalArts.

Ablutions was a kind of exit performance for us. It was moving from CalArts to Los Angeles. It was moving from graduate school into the professional community, so that our relationships then would be closer to Womanspace, as opposed to the school. The year before I graduated I had an important encounter with Judy. She had done Womanhouse, we had the performance program, and it was the last day of school, just before summer vacation. I had shown some sculptures in the crit class. I had taken some mannequins and put wax all over their faces, and then melted it, so that they looked like women whose faces were falling off. During the class, Judy said, “Suzanne, this has got real potential, this body of work. If you don’t stop splitting yourself between design and literature and this and that and the other and make a commitment to art, I’m not going to work with you anymore.” When I left class I ran around shaking and grabbed my friend Jill Soderholm and mumbled incoherently and ran off and grabbed somebody else. And then I just made this switch inside. I went out and caught Judy in the parking lot, and said, “Okay. I’ll be an artist.” I didn’t actually feel pressured; I didn’t feel like she was going to abandon me or anything. It had nothing to do with that. I knew that she was challenging me, which she had tried to do earlier, to acknowledge that I was an artist, not six million other things. And Judy knows about commitment, and I think that’s what the issue is, and she knows how to push you up against the wall, those of us who are more nervous about making commitments.

Judy Chicago, Suzanne Lacy, Sandra Orgel and Aviva Rahmani, Ablutions, 1972. Performance at Guy Dill’s studio, Venice, CA, Valencia, CA. Photo: Lloyd Hamrol. Courtesy of the artists and the Getty Research Institute.

MR: Is this the point at which you exited CalArts?

MR: And then the Woman’s Building was created in 1973?

MR: How much did you get paid?

SL: The first year it was something like $90 a month, and then it slowly went up. The max we ever got, I believe, was maybe six thousand one year, working full-time. So, needless to say, none of us ever supported ourselves completely on that, although we were trying. I either did carpentry, or at one point, around ’75 or so, I began working in a medical clinic as an emergency medical tech. They were able to train me because of my background. So I would work long shifts and basically do 48 hours of work from Friday night to Sunday night. It sure cut down on my social life.

MR: [Laughs]

SL: But it allowed me to function as an artist-teacher the rest of the week, which I did.

MR: What was the structure of the Woman’s Building?

SL: The Woman’s Building was a grand experiment. It was located in the old Chouinard art school, which we took over. The Feminist Studio Workshop was the core, the heart of the place, and it had 30 or 40 students a year. There were also various galleries, plus Womanspace Gallery. Marge Goldwater was one of the early curators of Womanspace. We had, for a while, a printing press and sisterhood bookstore. Once again, we did a whole lot of carpentry, renovating the place. My skills increased.

MR: There’s a great photograph in Faith Wilding’s book By Our Own Hands that shows you as a carpenter.

SL: With Ti-Grace the dog. I led carpentry workshops for the students. I belonged to a cooperative gallery called Grandview Galleries, named after the street we were on. It would provide us with a one-woman show once every year or two. When mine came up, I did One Woman Shows, which was an expression of the women’s community. The Woman’s Building was becoming a community, a mixture of feminists, feminist artists, and artists who were not feminists. In its early days, the openings were crammed. Everybody in town would come to them, including all the male artists. Everybody would come and get roaringly drunk and dance; it was quite an event for a period of time. That slowly dissipated, and it became known as a woman’s place. Then the openings were largely women and I remember a lot of complaints that some of the lesbians did not want men around. There was a constant struggle about what role men would play. Something happened in the West Coast feminist art movement that I don’t think was the case in the East Coast movement. We had such a strong community sensibility and focused so intensely on our relationships with each other that, except for some slightly aggressive attitudes toward men by women who had been fairly seriously damaged by them, for the most part men were not central to our theorizing. Men were not central to our emotional lives with other women, even though most of us were living with and loving men.

MR: Were you?