Termite Tracks: “Routine Pleasures” and the Paradoxes of Collectivity (2009)

by Michael Ned Holte

California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) co-published Afterall from 2002-2009. This essay was originally published in Afterall 22, Autumn/Winter 2009, and is reproduced with permission from the author. All original formatting has been preserved.

Manny Farber, Have a Chew on Me, 1983. Oil on board, 58 x 134 1/2 in. Collection of the Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach, CA. Courtesy of OCMA and the Estate of Manny Farber. Photo: Quint Contemporary Art.

For the rustle […] implies a community of bodies: in the sounds of the pleasure which is ‘working,’ no voice is raised, guides, or swerves, no voice is constituted; the rustle is the very sound of plural delectation — plural but never massive (the mass, quite the contrary, has a single voice, and terribly loud).

— Roland Barthes, “The Rustle of Language”1

Gathering Dust

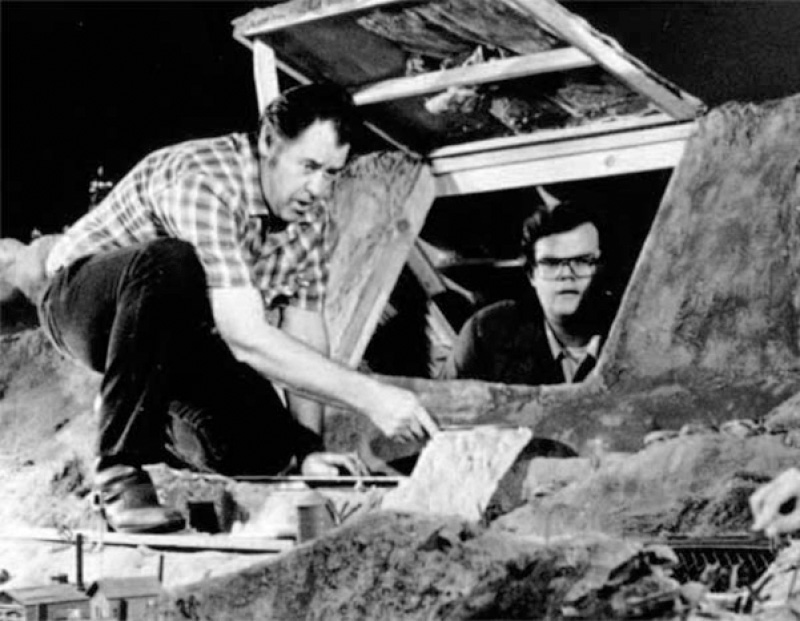

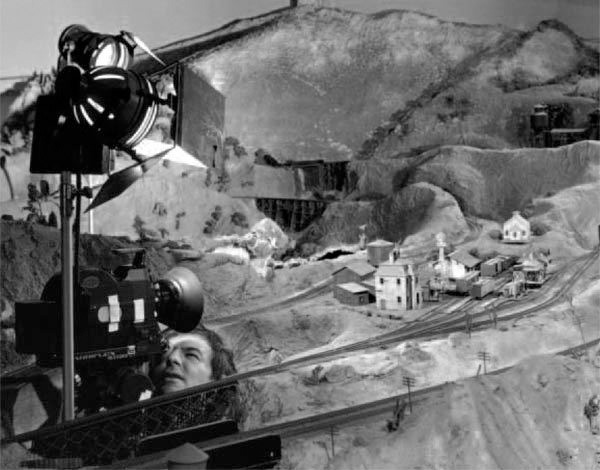

Like clockwork, from 1958 to 1993, the Model Railroaders Club would meet every Tuesday night near San Diego, in a hangar at the Del Mar Fairgrounds on Jimmy Durante Boulevard, and run model trains. The word ‘hobby’, implying the business of amateurs, is surely too moderate for the concerns of these ‘train people’, for whom work and leisure are seemingly indistinguishable. Approaching their train-playing with earnest seriousness, these men — with all-American names like Chester and Corky — appear trapped in a limbo between masculine responsibility and boyish fantasy. Signs posted near the club’s elaborate train set read, ‘When all else fails, try following directions’ and ‘It’s difficult to soar with eagles when you work with turkeys’, setting a droll tone for the intensity with which the group goes about their collective activity. Only chatting to ask a necessary question or to share a particularly noteworthy detail, their rustle may be difficult to see as anything but work, yet it surely exemplifies what Roland Barthes referred to as ‘plural delectation’ — a shared ‘language’ that develops over time while relying on histories and goals held in common, and many non-verbal forms of communication. Hidden well enough from public scrutiny as to seem hermetically sealed from the outside world, time stands still for the train people and their scaled-down version of small-town America — or, rather, time operates at a glacial pace, just at the edge of perception. A typical Tuesday night session would begin with the maintenance of the tracks. Several of the train people, apparently surprised to discover that entropy governs the train set just as it governs the outside world, dutifully note dust on the tracks and sweep it away, intent on making the trains run properly and sticking to the group’s strictly predetermined schedule.

This is the scene film-maker Jean-Pierre Gorin and his small film crew uncover and begin to gently infiltrate in the early 1980s.2With a stuttering series of false starts, the story of the train people eventually emerges as the remarkable feature-length film-essay Routine Pleasures (1986). But the film is not only the story of these train people: Gorin, who also plays the film’s charming narrator, slowly, incrementally reveals details of his own background to the viewer, constructing an accumulative story of displacement, difference and assimilation. As a visible presence in the picture, Gorin stands — literally and metaphorically — on the outside of the train set looking in. This is true, at least, in the beginning of the film, which takes place sometime around what the film-maker calls his ‘fifth Fourth of July’ — an anniversary that implies the presence of a threshold that is not only geographical but also ideological.

Originally from France, Gorin arrived in the US — to stay — in 1975, when he accepted a teaching position in the art department at the University of California, San Diego. Prior to moving to California, he was an active participant in the student and worker uprisings of May ’68 in France, and shortly thereafter the film-making partner of Jean-Luc Godard, who had gradually shifted his concerns from the nouvelle vague he had helped define toward the struggles of Mao, Marx and revolution. By most accounts Godard took his younger partner as an equal, even if some critics, given the elder film-maker’s outsized reputation, failed to recognise their efforts as truly collaborative.3

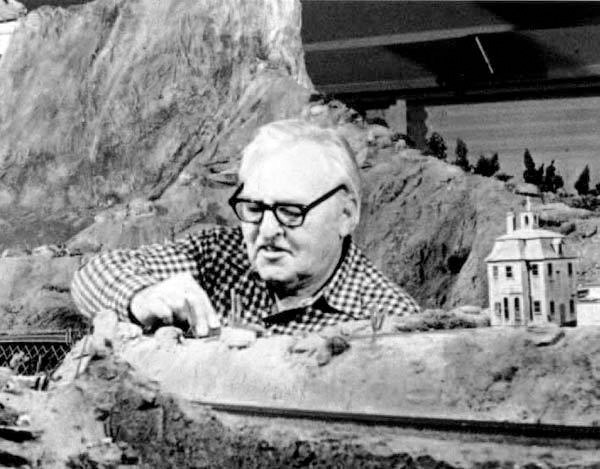

Still from Jean-Pierre Gorin, Routine Pleasures, 1986. Black-and-white and color 16mm film, 81 min. Copyright Babette Mangolte, all rights of reproduction reserved.

As a young student-activist, Gorin participated in the seminars of Louis Althusser, Jacques Lacan and Michel Foucault, and joined the editorial staff of Le Monde in 1965, where he worked as a literary critic until 1968. Godard and Gorin met for the first time in 1966, and, following the May ’68 demonstrations, began working together as the Dziga Vertov Group, named after the pioneering Soviet film-maker. The Dziga Vertov Group were active for a brief period of three years — during which they made, as a group, Vent d’est (Wind from the East, 1969), Luttes en Italie (Struggles in Italy, also called Lotte in Italia, 1970) and Vladimir et Rosa (1970); and Gorin and Godard together made, among others, Tout va bien (1972) and Letter to Jane: An Investigation About a Still (1972) — within a brief period of three years, before disbanding in 1973 due to differences of opinion concerning film-making strategy.4When asked about the split by journalist Penelope Gilliatt a few years later, Godard replied: ‘It was like a marriage. Perhaps no marriage should last too long.’ And then: ‘I may be wrong.’5Godard would continue collaborating with film-maker Anne-Marie Miéville (whom he eventually married); Gorin would begin making a films on his own.

Near the end of their collaborative endeavour, Godard and Gorin toured college campuses in the United States with Tout va bien, hoping to connect to a radicalised university audience while also raising some much-needed funds for making their films. Visiting UC–San Diego, the pair encountered Manny Farber, a professor in the art department and also a painter, but best known for his tough, idiosyncratic film criticism published in The Nation, Artforum, Time and elsewhere — his CV already included significant writing on Godard’s films.6Yet the relationship that quickly developed was between Farber and Gorin, and when a teaching position became available at San Diego a few years later, Gorin traded Paris for the American West.

Farber himself doesn’t actually appear in Routine Pleasures, but two of his paintings do, as well as some photographs of him as a teenager on the football field and, years later, in his studio — not to mention several incisive excerpts of Farber’s writing that, as Gorin explains in the film, gnaw away at the film-maker. This is where the tracks begin to intersect.

Termite Tracks

Routine Pleasures is an essay film in which Manny’s work plays an essential role and my closer-than-close relationship to him is abundantly evoked. It is not a documentary on Manny (he never appears in it). It is a meditation on method and work, the American landscape, the male imaginary, the high and low of American culture, the materialist nature of artistic imagination, friendship, the endless obsessive pursuit of details… In short, if asked what it is about, I find myself forced to say simply that it is a film about about.

— Jean-Pierre Gorin7

Routine Pleasures is structured as a numbered sequence of false starts in which the number ‘1’ appears as the title screen halfway through the film, some time after the numbers ‘2’, ‘3’ and ‘4’. Film is a medium governed by the possibilities of editing — many auteurs, from Eisenstein to Hitchcock to Godard, have reminded us that film is, in essence, montage. Rather than covering his tracks in the editing room, Gorin frames them in the foreground and builds the film around them, recalling tactics — including an arsenal of inter-titles — similar to those used to great effect by Godard.

Production still from Routine Pleasures, featuring Farber’s painting in the background. Copyright Babette Mangolte, all rights of reproduction reserved.

To the extent that one can be located, the subject of Routine Pleasures — and the side-winding, stuttering, spiraling approach Gorin employs in assembling it — is emblematic of what Farber defined, and valorised, in his bare-knuckled essay ‘White Elephant Art vs Termite Art’ (1962), as the ‘termite art tendency’, in which an artist approaches a subject by eating away at it over time and from the margins.

‘A peculiar fact about the termite-tapeworm-fungus-moss art,’ writes Farber, ‘is that it goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.’8He takes as his examples the apparently aimless ‘squandering-beaverish endeavours’ of Laurel and Hardy in Hog Wild (1930) and the ‘hoboish spirit’ of John Wayne’s performance in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) to demonstrate how the chewed product of termite art leaves behind significant gaps, holes and voids — limbos the viewer fills in order to complete the work. ‘White elephant art’, on the other hand, or ‘masterpiece art’, is all too obvious in its totalising strategies, always overcompensating and overplaying its hand.9

Gorin’s disordered approach to editing, and his willingness to occasionally steer off the tracks, exemplifies the termite approach. ‘The important trait of termite-fungus-centipede art,’ Farber wrote in 1971, ‘is an ambulatory creation which is an act both of observing and being in the world, a journeying in which the artist seems to be ingesting both the material of his art and the outside works through a horizontal coverage.’10Farber’s notion of termite art is often at play in his film criticism (perhaps especially in his later collaborations with his wife Patricia Patterson), but is most readily apparent in his own still life paintings, which typically position a tabletop carefully littered with objects — flowers, fruits, stencils, handwritten notes, Lotería cards, tools, toy train tracks — as the picture plane of the canvas.11Farber’s tabletop landscapes are without beginning or end, and the sheer amount of visual information that the viewer is required to scan exacerbates this accumulative, ad infinitum condition. Switching from black and white to colour — like Dorothy leaving the grey plains of Kansas and arriving in vibrant, hallucinatory Oz — Routine Pleasures pores over the surfaces of two Farber paintings: Birthplace: Douglas, Ariz. (1979) and the still-in-progress Have a Chew on Me (1983).

The film, which begins as an intimate study of a group of Pacific Beach model train enthusiasts, frequently jumps tracks to become Gorin’s autobiography since his arrival in the US, as well as a compelling portrait of Farber and his ideas and paintings. Gorin, writing alongside Patrick Amos in an essay on Farber, observes that:

At stake in these paintings is the mapping of [Farber’s] mental processes; and the works’ originality holds to his anti-dialectical approach, the pluralist strategies that tend to produce contradictions within the picture, and within each of its gestures, without offering any resolution. In their refusal to coalesce into a single image, their reliance on a cumulative ‘and… and… and’ advance, these paintings operate as rhizomatic arrangements, boards that can be entered and exited at any point, where each object in the field operates as a switching device, where ideas of closure and origin seem irrelevant.12

That notion of the run-on sentence — ‘and… and… and’ — recalls Gorin’s own characterisation of Routine Pleasures as ‘a film about about’. And, of course, it also characterises the ‘termite tendency’.

Still from Routine Pleasures, 1986. Copyright Babette Mangolte, all rights of reproduction reserved.

Farber provides a foil to the train people, but also to Gorin. Farber, as we learn in Routine Pleasures, refers to Gorin as his ‘twin brain’. Gorin’s affection for — and desire to please — his elder ‘sibling’ is obvious, but the phrase hangs in the air and spirals outward through a seemingly endless chain of pairings and partnerships that transports the film increasingly further away from a central subject: Gorin and Farber; Farber and the train people; Farber and Patterson; Gorin and Godard; Poto and Cabengo, the twin girls who share an invented language in Gorin’s 1978 film Poto and Cabengo; and even Chuck Jones and Gustave Flaubert — the unlikely duo to whom Routine Pleasures is dedicated without further explication.

Routine Pleasures, like Poto and Cabengo before it, lays tracks around the notion of collectivity, and finds in Farber’s termite tendency the perfect method with which to interrogate it.13Several times in the film Gorin admits to unspecified bouts of nostalgia — perhaps nostalgia for a US discovered from afar, through its cinema. Or is it his nostalgia for his own history of collective endeavour? Routine Pleasures could be seen as Gorin’s attempt to reflect, if not reconcile, the aspirations and disappointments of the past amidst the ‘humdrum’ termite activity of the present.

A Model Collective

Just because you’re an ex-Marxist, don’t feel obliged to start a film with the opening of a toolbox.

— Manny Farber, quoted in Routine Pleasures

At the time of Gorin’s arrival in the US, San Diego was as culturally and ideologically different from Paris as Kansas was from Oz. As the narrator of Routine Pleasures, Gorin describes the film as ‘a small-scale epic: America, under budget and in a shoe box’. Centred on the collective but hermetic and nostalgic activities of the train people, Routine Pleasures reveals how far the filmmaker had moved away from the didactic political demonstrations he had made with Godard.

Formed in the volatile wake of the events of May ’68, it is difficult to evaluate the relative success or failure of Godard and Gorin’s collaboration. ‘The problem,’ Godard once stated, ‘is not to make political films, but to make films politically.’14The films of the Dziga Vertov Group were frankly experimental, and the agenda of ‘making films politically’ was anything but singular or static, instead representing an attempt to hold a mirror to a constantly shifting present.

Referring to Pravda in 1970, Godard stated: ‘We made a movie, then criticised it. It was a disaster, and we tried to find out why it was a disaster. I find now that 10 per cent of each film is good and 90 per cent is bad. We are always learning. The important thing is to look at film from a political point of view rather than an individual point of view.’15

Further, what seems clear is that the films did not connect with as large an audience as they hoped. Even Tout va bien, which featured stars Jane Fonda and Yves Montand in leading roles, failed commercially by all accounts. Godard’s biographer Colin MacCabe, whose own relationship to political ideology may be nearly as contentious as his subject’s, recently argued:

The great problem confronting the collaboration, a problem that Gorin characterises in terms of ‘anguish’, was that of the audience. The enormous weakness of the Dziga Vertov position was that it assumed that a revolutionary politics would provide another audience […] a militant audience for whom the screen would be a blackboard and the soundtrack merely the beginning of a conversation. In fact, when Godard and Gorin made a film which genuinely tried to address student militants, not only did the commissioning broadcaster refuse to show it — on the by now predictable grounds that it was not political enough — it also failed to find any political audience whatsoever.16

One of the noteworthy achievements of the May ’68 strikes was the common ground located between striking students and workers. Yet it is not clear that the films of the Dziga Vertov Group were fully embraced by either coalition. Unlike some contemporaneous collective film-making efforts, such as SLON or the Medvedkin Groups, the notion of ‘making films politically’ was not necessarily predicated on getting the means of production in the hands of workers — or even getting a camera in the factory. As MacCabe notes,

The title Lotte in Italia might summon up images of students and workers clashing with police, but for the Dziga Vertov Group, the struggle is always the struggle between sound and image. More than thirty years later, it still amuses Gorin that the film was shot almost entirely in Paris, because the whole thrust of its analysis is that is impossible to ‘see’ a social situation.17

Production still from Routine Pleasures. Copyright Babette Mangolte, all rights of reproduction reserved.

In Routine Pleasures, Gorin burrows into the middle of the tight-knit club, developing genuine friendships with the train people — exemplifying what Farber describes as the ‘act both of observing and being in the world’. The initiation period is complete when Corky, the group’s de facto leader, adds an exacting small-scale replica of Gorin’s dented Citroën to the Pacific Beach train set. One might even conclude from the humorous, diplomatic gesture that Gorin has thoroughly enacted Godard’s ongoing obsession with America by actually becoming an American: the termite negotiates its terrain from inside rather than at a remove.

One could view Routine Pleasures as a return to a familiar, anthropological brand of documentary film-making — and therefore a conservative rejoinder to Gorin’s earlier, more radical attempts ‘to make films politically’ with Godard. At the same time, recalling Godard’s stated ambitions for the Dziga Vertov Group, Gorin is also holding a mirror up to his present and imbricating himself within it, suggesting a more personal intent to the film. Such parallels are complicated, however, by the notion that the present of the model railroaders in Routine Pleasures, much like Ronald Reagan’s contemporaneous vision of ‘morning in America’, is also a nostalgic mirror image of the past.18

Ironically, Gorin seems to position the train people as a — pardon the pun — model collective. The survival of the group seemingly results from the intimacy and stasis of their collective endeavour, in their resistance to an outside world that only enters their inner sanctum on the Del Mar Fairgrounds as a small-scale representation. In pointed contrast to the Dziga Vertov Group, there was never an aspiration to find an audience, let alone participate in changing the world.19Instead, the train people swerve sharply inward, striving collectively only for the maintenance of the train set, or what one of the train people refers to as a ‘temporal landscape’.

Gorin never fully joins the club — his interest is not in the trains, but in the people who collectively obsess over them — and the tension between his role as an individual and his role as part of a team (with the train people, with Farber, with Godard) is the engine that drives the film. One of the most poignant moments in Routine Pleasures occurs when Corky reveals that he is a film-maker too, and fell in love with his wife Barbara while chasing trains with his Super-8 camera in tow. For Gorin, access to the world of the Model Railroaders Club is predicated on the trade of his leftover footage — an economy of means that surely would have resonated with the ‘ex-Marxist’.

‘I realised it wasn’t going to be easy to live up to Corky’s film-making standards,’ says Gorin, as he and the train people gather for a private screening. A title screen, borrowed from an 1896 actualité, reads ‘Friendly Party in the Garden of Lumière’ — did Gorin screen this early cinema artefact for the train people? — and is followed by Corky’s hand-held footage of the Royal Hudson line thundering out of Fresno toward Bakersfield. ‘What happened, Corky,’ one of the men teases, ‘did you lose your tripod?’ And Gorin, in his voiceover, wonders aloud, ‘Could I ever hope to have such a hold on an audience?’20

Narrating this sequence with a generous disposition, it seems likely that Gorin’s bemusement is not at the expense of the train people but at his own predicament of joining the plural delectation of the film screening while caught in a limbo between present and past, between individuality and collective interests, between Kansas and Oz. As an autobiographical reflection of Gorin’s collective ambitions, Routine Pleasures leaves more questions than answers and more beginnings than endings. Its run-on, ‘and… and… and’ structure suggests the termite’s work is ongoing and never fixed in place.