The Art Lover: Galka Scheyer’s Higher Calling

by Darcy Tell

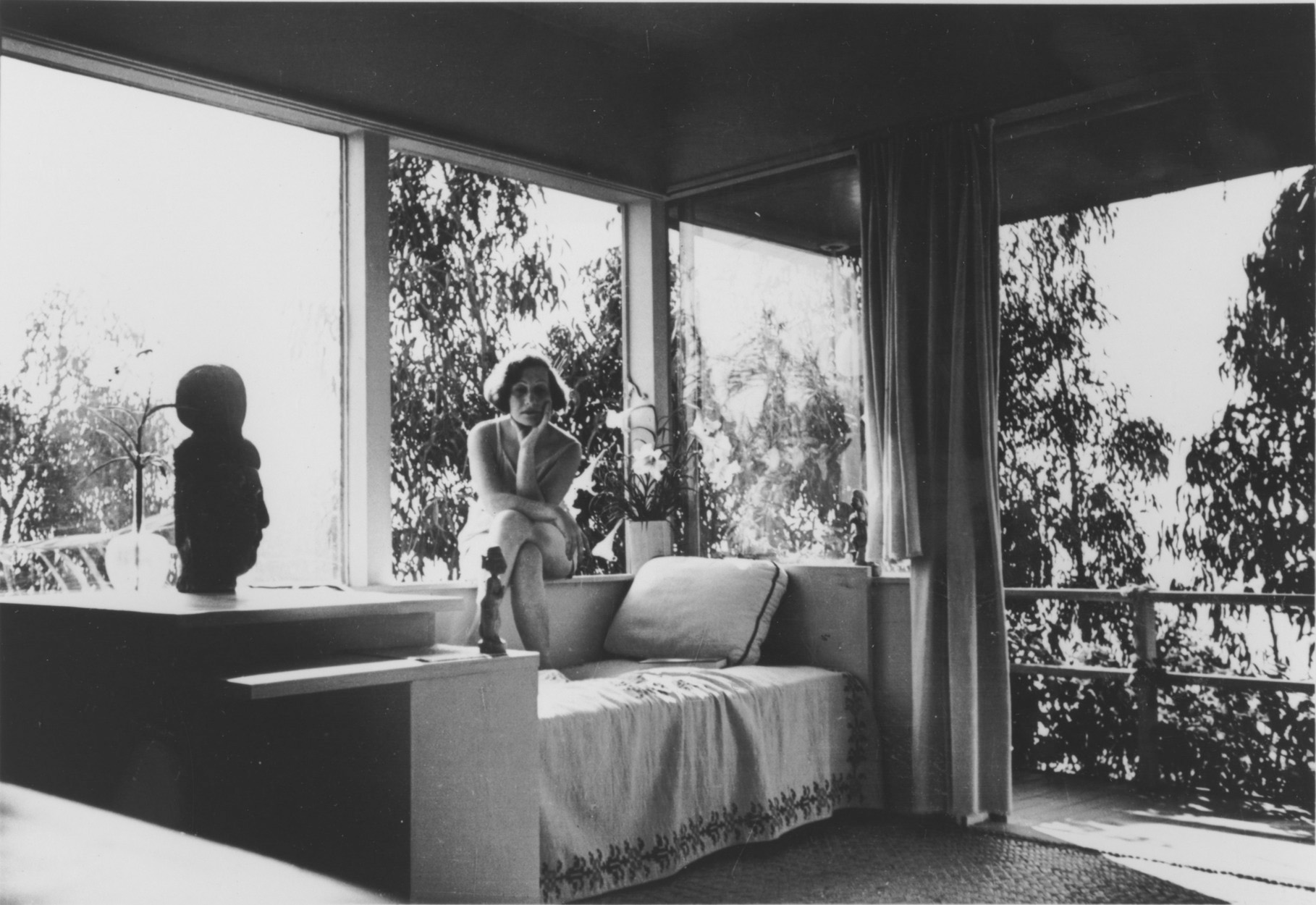

Galka Scheyer in her Hollywood Hills house designed by Richard Neutra. Lette Vaselka, Galka Scheyer in Sunsuit, Seated on Windowsill, ca. 1940-43. Photograph, 3 1/2 x 4 3/4 in. Courtesy of the Blue Four Galka Scheyer Collection Archives, Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA.

As Mysterious as the essence of creation is, so mysteriously does the essence of art arise from it. Like the tensions between that coming into being and the world, so arise the tensions between the viewer and the art work. These bridges, which lead to experience, begin to form. The viewer will become silent and the work will begin to radiate life. The rays will resonate and the work will begin to radiate life. The rays will resonate and begin to resound in the soul. This inner resonance of feeling is the experience of art. —Galka Scheyer, 1923.1

I shall never forget those inspiring days when you initiated me into the sacred world of art. I shall never forget you really did make me what I am today. —Galka Scheyer to Alexej von Jawlensky, 1936.2

The facts of Emmy “Galka” Scheyer’s activities in Los Angeles are already well known to people who follow the development of modern art in California. In 1915, a young upper-middle-class German student of painting saw a picture, Alexej Jawlensky’s The Hunchback (1911).3She was so moved that she decided she must meet the painter, and by 1916 she was modeling for him. The next summer she visited Jawlensky and his family often in Switzerland; through him she met many important avant-garde artists. By 1919 Scheyer had stopped painting to promote Jawlensky’s work.4

Soon, Scheyer had mastered art promotion and was working energetically as an impresario for Jawlensky, with whom she had a relationship that was part close friendship, part business arrangement. In 1920–21 she mounted a couple of well-received shows of Jawlensky’s work that traveled around Germany. She had by that time made many new connections in the German and European avant-garde, had written a monograph on her idol’s work, and started to buy works of art by Jawlensky and other artists for her own collection. In 1923 she decided to expand the scope of her work. She proposed to unify Jawlensky and three modern painters she had met in Jawlensky’s ambit—Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, and Wassily Kandinsky—into a “free group”; on March 31, 1924, the five signed a contract in which Scheyer became the artists’ legal representative in the United States.5

She set sail for New York in May 1924. From the beginning, her project was to “sow the seeds of a love of art,” but the contract assumed Scheyer would be selling paintings as well as arranging exhibitions and lecturing. Sales would help cultivate American collectors of German avant-garde art. After a frustrating year in New York Scheyer moved to Northern California. Living on stipends from home, she settled in. Her lively personality (about which more later), impressive artistic connections, and thorough knowledge of international modernism immediately attracted attention. Soon she was lecturing regularly (crowing that she earned more than professors) and had made friends among local modernists like Dorothea Lange, Lange’s husband, Maynard Dixon, and the painter and museum director William Clapp, who in 1926 gave her an unpaid job as European representative of the Oakland Museum.

In the Bay Area, Scheyer went to work with the same energy and brisk efficiency she had shown in her work for Jawlensky, organizing shows for her group, the Blue Four, as often as she could, sending out hundreds of letters, and meeting local artists, dealers, professors, collectors and arts administrators. Her letters to the Blue Four painters at home are more often optimistic than not (“Following my newly acquired [American] approach to life, I allowed myself neither tears nor thoughts of disappointments . . . I decided to live like an adventurer”), though Scheyer was not shy about telling them about her struggles, which do seem to have been considerable.6By 1928 she had given numerous lectures and gallery talks and organized six exhibitions. She had also made a number of modest sales to several collectors, the kind of people Scheyer and the Blue Four called “art lovers”: “People who have little or no money [but] seem to be much more able to show enthusiasm than those who are better off, ” as Kandinsky described in a letter. Her letters home reveal again and again Scheyer’s enthusiasm for life in America, often expressed in subtle appreciations and sly criticisms of the country’s people and landscape. The Blue Four marveled at her courage and energy.7

During five years in Northern California Scheyer’s work had often taken her up and down the West Coast. By summer 1929, dreaming of a rich Hollywood clientele and encouraged by an invitation to organize solo shows for the Blue Four at the Braxton Gallery in Hollywood, Scheyer moved south. She settled permanently in Los Angeles in 1930. Scheyer had met architect R. M. Schindler on her first trip to Los Angeles and moved briefly into his Kings’ Road house.8She showed consigned pictures and her own collection in her rooms, often giving talks for friends and clients in front of the works, a method she had developed in San Francisco. As usual, she had warm friends and made more: Gela and Alexander Archipenko, Schindler, Richard Neutra, Beatrice Wood, Walter and Louise Arensberg, Ruth Freeman, and the mystic philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti. Scheyer added several important clients during her first years in Los Angeles, notably the Arensbergs, the collector Ruth Maitland (who became a good friend), and, briefly, Josef von Sternberg and a variety of stars and collectors from the film industry.

Scheyer visited Germany in 1933, but left ahead of schedule, alarmed by the deteriorating political situation. In the preceding months, the public and state had begun to turn against avant-garde art. In September 1932, the Bauhaus in Dessau was closed down and moved briefly to Berlin. Kandinsky and Feininger went along. The following spring Paul Klee was suspended from his teaching job in Dusseldorf. By 1934, forbidden to show and without support, Kandinsky and Klee left Germany. Jawlensky, also forbidden to show, was stranded in Wiesbaden, almost completely debilitated by arthritis and nearly destitute. In the next few years, as they became more desperate for money, the painters were unable to make the kind of concessions to Scheyer they had during the early years of her enterprise. Out of necessity, the painters reached out to anyone able and willing to help them sell their pictures, and Scheyer lost her status as their exclusive representative in the United States. She nonetheless seems to have done the best she could to help her friends, sending Jawlensky money (sometimes borrowed from sympathetic American friends), working with other dealers, lowering prices (if the artists let her), and always organizing shows and more shows. Sales were few, however, and tensions in the group rose.

As the Depression progressed in the United States and the political situation in Germany degenerated, Scheyer (who had always lived hand-to-mouth) found herself in a difficult position. Eventually, when the Nazis “confiscated” her family’s business in Brunswick, Scheyer was left without the monthly allowance that had helped support her since 1925. She tenaciously continued her efforts to promote the Blue Four, but there were contretemps with the gallery owners she was increasingly forced to work with. Her hopes for success in Hollywood dimmed, but Scheyer pressed on.9

After her return from Europe, Scheyer briefly rented a tiny apartment designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Finding the walls (“concrete frou-frou,” she called them) unsuitable for showing paintings, Scheyer bought a piece of land in the Hollywood Hills, and, using a “bit of money set aside,” she asked Neutra to design a modern house for her, paying for construction as the work progressed.10Photographs show pristine modern interiors, and in her letters she described the echt-California lifestyle she looked forward to: she wanted to garden naked in the sun, sleep outdoors, and watch the fog roll in up the mountain. In the evening, “billions of lights light up; the pictures on the walls begin to come alive, the glass door is open, and everything becomes indescribably festive and beautiful.” Finally, Scheyer could live as she “always wished to. In a most beautiful natural setting close to a city. With modern rooms and freedom to move about. From a truly modern architect. Congratulations to myself!”

Scheyer had asked Neutra to design a house devoted to showing art, and she used the new space for exhibitions, lectures, and private gallery visits even before it was finished. At first she seemed to have some success. By early 1936, she wrote the Blue Four that Hollywood was having a Galka Scheyer craze; she was friendly with Marlene Dietrich and Harpo Marx, both of whom borrowed works to show off at parties, and Greta Garbo, who “ran like a child from the paintings to the flowers [but] said she understood nothing” about Scheyer’s collection. Scheyer lectured often, an exercise she assured the Four was hard work:

Twenty lectures in my house . . . hanging pictures, so splendidly, so lovingly, each related to the others [paintings] with glorious names, Rousseau, Van Gogh, Cezanne, from the dead, and modern French artists . . . in combination with all the treasures that my Blue Kings have lent me. Hanging takes an entire day. Cleaning, filling the house with flowers, a second day. The lecture, a third, and cleaning up afterward, a fourth.11

Though the stars came, they didn’t buy, and Scheyer made little from sales. She was in debt, and in April 1938 she had a serious car accident. Even so, Scheyer’s social life seems to have been active and happy. She had had a falling out with the Arensbergs in 1934 over a sale, but regularly saw a group of sympathetic, mostly female, friends: Ruth Freeman, Marjorie Eaton, Beatrice Wood, Ruth Maitland, and various refugees who arrived in Los Angeles. She organized shows (and often had to split her commissions with other dealers), taught children’s art classes, lectured for adults, and bought works for her collection. In the fall of 1944 she was diagnosed with cancer. When she died the next winter, Jawlensky, Klee, and Kandinsky were already dead; only Feininger outlived his friends.

In the twenty years she had spent in California, Scheyer had never stopped buying for her own collection, swapping and using money as she could to acquire new works. At the time of her death in 1945 the collection included more than four hundred works of the highest quality by the Blue Four and others, not including works that she still had on consignment at the time of her death. When she fell sick in 1944, Walter Arensberg suggested that they work together to see that Scheyer’s and the Arensbergs’ collections stayed in California, which in 1945 had no modern art museum. The three signed an agreement with UCLA to donate both collections as long as the university built a museum to exhibit the art by October 1950. When UCLA reneged on its agreement, the Arensbergs left their art to the Philadelphia Museum; Scheyer’s trustees and brothers transferred the Galka Scheyer Collection to the Pasadena Art Institute (which became the Pasadena Art Museum and is now the Norton Simon Museum) in early 1953. Since then, Scheyer’s choice taste has been celebrated. Her collection, the first important collection of German modernism in Southern California, is known around the world for its high quality and beauty.

“Prophetess of the Blue Four,” San Francisco Examiner, November 1, 1925. Pictured: Galka Scheyer, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Alexej Jawlensky.

I did not pay enough attention to Galka[;] if I had I would be worth $250,000 today. She had vision and understood the importance of modern art. . . . I learned so much from her. . . . [W]hen she died I cried, because I realized how much she had done for all of us. —Earl Stendahl, 1961.12

Galka repelled me at the start of our acquaintance but now I find myself wishing she would drop in once more before leaving. She is a dynamo of energy . . . [with] insight of unusual clarity, and an ability to express herself in words, brilliantly, forcefully, to hit the nail cleanly. . . . She is an ideal “go-between” for an artist and his public. —Edward Weston, 1930.13

When I first met Galka Scheyer I wanted to run. She was short, red-haired, plump, loud voiced—then I took myself to task . . . The second time we met, I let go of esthetics and listened. I discovered an intelligent, caring woman and we became good friends. —Beatrice Wood, n.d.14

Through repetition, the facts of Galka Scheyer’s story have taken on an air of inevitability: she has come down to us as a kind of Weimar Auntie Mame engaged in a fool’s errand to promote modern German art in philistine America. That she left the first collection of first-rate modern art in California seems almost accidental. As with any oft-repeated stories (for example, the story of Albert Barnes), though, it’s never a bad idea to take another look. In the case of Scheyer, a second look shows quite a bit of strangeness in the narrative, and more importantly makes us wonder if something is missing, some context, perhaps, or stray fact that never got in?

The first thing that strikes me is how summarily many accounts of Scheyer written in English have treated the one thing that sent her to America: her almost messianic belief in the ideal, spiritual power of the modern art she adored. German modernism of this time, which Scheyer fervently took up (for life, it turned out) around 1916, was shot through with diverse cultural influences and took a number of forms; many forward-looking artists in German-speaking countries—for example, Dadaists, Bauhauslers, Lebensreformers, members of the Wiener Werkstätte or other arts-and-crafts-influenced movements—shared a desire to reform, renew, shake up, or remake life and culture. (Scheyer’s earliest contact with some of these movements came during the time she spent in Jawlensky’s household in Ascona, Switzerland, a center of Lebensreform.)

The work of the Blue Four, cultivated in this cultural milieu (and unified only in the sense that Scheyer convinced them to band together for her project to promote their work in America), sprang from the same kind of impulses to transform. Singly, each painter sought something they called the “spiritual” through their art, often set in opposition to the “material.”15“Spiritual” seems to have been an elastic term. In letters among the Four and Scheyer, the painters repeatedly described how they wanted to portray interior states or meaning with feeling and resonance that moved viewers. They sought to go beyond exterior motifs to set down transcendent expression using new artistic languages. They rejected mere formal, retinal-perceptual experimentation and used modern pictorial innovation as a means to profound idealistic ends. Letters between Scheyer and the Blue Four refer often to their common belief in the power of art to move people to see life more profoundly; a 1940 letter to Jawlensky was typical: “When people […] look into their souls, your work [will] be prophetic for them . . . since life works from the inner to the outer and not the other way around.”

These very deeply felt ideas have been given scant attention in most versions of Scheyer’s years in California. Scheyer’s vocation for modern art—and I mean vocation in the religious sense—is something foreign and perplexing to us now, as it certainly was to most Americans in her day. Steeped as we are in postmodern irony, high-flown discussions of artistic idealism now understandably appear to us naïve or embarrassingly earnest. We often prefer to examine the descriptive, technical or promotional sides of art and the art world, and pay even closer attention to the social prestige of art collecting, reading about collectors, photographed in massive penthouses or Park Avenue co-ops. Rarely do we consider the substance of the art we see there.

Our contemporary formation and sensibilities, then, dispose us to downplay something that has never been adequately defined (and perhaps can’t be adequately defined): What did Scheyer find so moving in the paintings she collected and promoted, what was so important and meaningful to her that she devoted twenty years of hard work to it, much of it thankless and underpaid?

The hybrid nature of her enterprise—she was a proselytizer, collector, dealer, teacher, immigrant, and acolyte—complicates matters further. We find it easy to understand a completely commercial avocation or a totally aesthetic one, but together they seem contradictory. We know from letters back and forth between Scheyer and the painters that the original ideas behind a Blue Four association included the aim of escaping the conventional art dealer–artist relationship. In 1924, for instance, she wrote Feininger that “if it weren’t for the thought that I can sometimes spare an artist’s soul” the unpleasantness of working with dealers, she wouldn’t have subjected herself to such a “psychologically unpleasant profession.”16In 1936, when the Blue Four criticized her for few sales, she wrote defensively that there were few sales because Americans had “not yet mature[d] enough to live with . . . spiritual works,” and reminded the painters that “the Blue Four was founded . . . to share the spirit embodied in these works and to get away from art dealers.”

Nonetheless, Scheyer embraced commercial activity straightforwardly, without apology, as a means to this end. It is clear though that the ambivalence and incomprehension that dogged her work in California, not helped by her unusual situation as a foreign, unmarried, professional woman, had a greater effect on Scheyer’s failure to market the Blue Four during her lifetime than has been acknowledged.17By the time she arrived in California, where the cultural infrastructure was rudimentary at best, Scheyer was a seasoned pro. More importantly, she was a representative of modern German culture at a time when it was considered extremely advanced. We conclude from the newspaper coverage she got that Scheyer was something of a curiosity to the larger public, and we know that she did manage to forge strong connections among some Americans interested in the modern movement. But on the ground, especially in Southern California (in the north her opponents seem to have been straight-up artistic and social conservatives), her forceful presence often worked against her.18

Scheyer’s inability to hide her powerful sense of cultural superiority must have put off new acquaintances and business associates, some of whom found her difficult, capricious, and too perfectionistic to work with.19It also seems likely that American collectors and dealers, accustomed perhaps to maintaining a hypergentility to counteract the ingrained American distrust of anything longhaired or artistic, would find fault with Scheyer’s demeanor. Scheyer, on the other hand, never dissembled: she was a loud, enthusiastic, overbearing, businessman-like, didactic, heart-on-her-sleeve woman, driven by a need to spread the gospel of modern art. The condescension and misogyny (and likely anti-Semitism) she met, which she must have recognized, are startling even today.

In contrast to the comments by Americans at the beginning of this section, the letters between Scheyer and the painters show them to have been peers; even through periods of doubt and misunderstanding, their friendship and admiration came through. The painters talked business, gossiped about the art world, and discussed their work. They often called her “pretty girl,” though whether in good old-fashioned courtliness or in memory of Scheyer’s younger self (from the photographs, a shapely, petite soubrette) is not clear.20Scheyer’s letters to her friends often praised the freedom and mobility of American life—she became a citizen in 1931—but the primitive state of cultural evolution in America (as she and the painters often put it) irritated or amused her by turns.

To reframe accounts of Scheyer’s life and work in California, the various phases of her life must be knit together more critically, putting two things at the center: her didactic advocacy of the Blue Four and her own drive to collect. Again and again, through the correspondence that has been translated, we see that her metaphysical side was a guiding force. In English, though, most often discussions of the practical—shows, press, and collectors—overshadow the spiritual. It’s important to understand too how Scheyer’s educational activities, collecting, dealing, cultivation of collectors, and organization of shows, served her higher aims—or failed to do so. Last, further scholarship is needed that examines the connection between Scheyer’s private life and her personal devotion to the art of her time, perhaps looking at her initial exposure through Jawlensky to bohemian culture in Ascona, her ties to Krishnamurti and his circle, and even her pedagogical work in Los Angeles.

If we turned our focus to the woman herself, not just her relation to the artists she promoted and her monetary success or lack thereof, perhaps the meaning and purpose that drove her would become clearer—and we might understand this tough and single-minded woman better on her own terms, inside to outside and not the other way around.