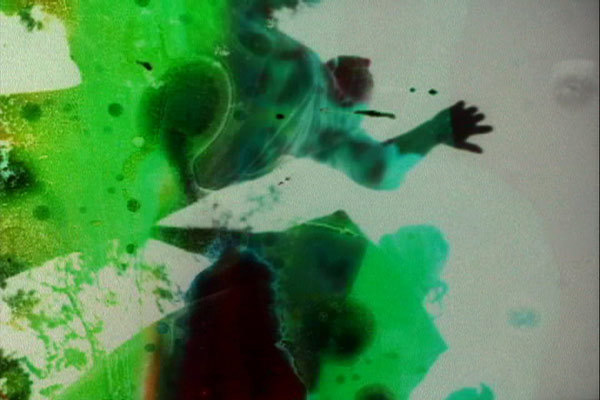

Jennifer West, Daisies Roll Up Film (16mm color and b&w film neg rolled with hard boiled eggs, oranges, lemons, avocados, pickles, green apples, milk and watermelon – a remake of a scene from Vera Chytilova’s 1966 film, Daisies – rolling off the bed performances by: Mariah Csepanyi, Finn West & Jwest, lit with black light & strobe light), 2008. 5 min, 53 sec. All images courtesy of MARC FOXX, Los Angeles.

Los Angeles-based artist Jennifer West has been making her remarkable ‘cameraless’ films–in which film stock is treated with myriad substances, from household cleansers to campfire smoke, and subjected to indelicate acts, like being licked, hammered or skateboarded on–for over a decade now. Quinn Latimer talks to West about this alchemical meddling, drugstore culture, riot grrrls, very long film titles, and an even longer list of influences ranging from Dutch masters to Len Lye to the gilded mythology of the Golden State.

Quinn Latimer: I was struck by something that the curator Valerie Cassel Oliver wrote about your films: that, rather than embracing the iconic cultural moments they explore, in “an act of sentimental or reverent nostalgia [you] extend them through reinvention.”This seems to me so true about your work, which could easily be steeped in nostalgia—with its reclamation of experimental-film traditions and its celebration and critique of past cultural moments: sixties-era happenings through nineties riot grrrl. Yet your work isn’t nostalgic in the least. Is this something you ever worry about? You’ve mentioned in the past that you usually don’t use old film projectors to project your films, because the whirring sound is too nostalgic.

Jennifer West: First off, the fact that nineties riot grrrl could be read as nostalgic is crazy but true. It still feels like we are coming out the nineties, waiting for the 00s to define themselves as an era—though it was twenty years ago now. But to get back to your question: I make sure that each work has a tension set up between the subject—the materials and actions—and the images (if there are any) in order to produce a new thought about it or to make contradictory associations. I’m always looking at how histories circulate, translate, mutate, and inform what is happening now. Some of my works look at and/or look back to popular, underground, avant-garde, even what I call “drugstore” culture—that’s everything at the local CVS drugstore, where I get many of the supplies for my work.

With each film, I have something specific to say about the moment or subculture that it depicts. Some, although certainly not all, of the subjects could be idealized, romanticized, even exoticized: road trips, riot grrrls, camping, the beach, DIY, skating. And this romanticization can be especially true outside of the US. But a lot of the work comes out of something I hit on in about 2006 when I started thinking about what materials, foods, substances, and actions are evoked in books, music, films, perfumes, specific artist’s works, or specific places; and how these materials reflect back upon the culture itself.

One example would be my film

Idyllwild Campfire Smell Film (16mm film neg lit by the campfire and treated with bug spray, white gas, gin, sweat, smoke, pitch, marshmallow, beer, wine, pit toilet, dirt, sap, tent & sleeping bag—featuring marshmallow roasting by a bunch of friends), in which these intense and varied smells are used to evoke a sense of humor and to complicate romantic ideas of the communal campfire.In

Roadtrip Between LA and Seattle Film (16mm color negative, positive and b&w negative scratched with tumbleweed, tire treads, pine needles, sprinkled with BlackJax extreme energizer pills, coffee, donuts, hot Cheetos & doused with gasoline & gatorade), the legal speed pills and junk food contemporize the “road trip,” and the black-and-white and color film highlight the transition from early road films to, say, a color film like Monte Hellman’s

Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), which, incidentally, is itself a materialist film of sorts, since the film melts in the projector at the end.

This is also reiterated in the way I present the work as digital projections—the format of today—so that the subjects are considered in the medium of their time. Being from a generation in which I remember distinctly the day I learned to burn my first DVD, which at the time cost loads of money, the power to produce my own work was crucial.

QL: You mentioned that your films are inspired in part by “drugstore culture.” Are places like CVS simply sites where you can purchase your materials, or do the stores themselves—either as concrete spaces or as metaphors for consumerism—inspire you in some way apart from their direct utility?

JW: The stuff and people in any local drugstore in any neighborhood serve as a reflection back upon culture—both fulfilling certain cultural desires and

Jennifer West applying nail polish to film strips for Lavender Mist Film/Pollock Film 1 (70mm film leader rubbed with Jimson Weed Trumpet flowers, spraypainted, dripped and splattered with nail polish, sprayed with lavender mist air freshener), 2009. 46 sec. Photo: Finn West.

as an inventory of social and even political moments in time. “Convenience stores” operate in a similar way but are geared more toward the mobilized person. So, as you say, the drugstore’s “metaphor for consumerism” becomes an inventory of cultural effects. You might have thirty types of energy drinks but will also now have a section of “natural” or organic makeup. On the other hand, the convenience store also contains a lot of raw materials or supplies that hark back a generation or two. But, as a concrete space, it’s great how the drugstore puts everyone on the same level, in the same place, because at some point everyone ends up needing Band-Aids, aspirin, or a neti pot. And that’s how my materials operate: they personalize but also unite people on a base level.

When I was making films about particular musicians, I was thinking how Nirvana lyrics evoke all kinds of abortive substances from laxatives to antacids, bleach to pennyroyal tea (which I used in my

Nirvana Alchemy Film).In contrast, Zeppelin was mostly sweet or romantic things like custard pie, tangerines, wine, flowers, and lemon, while the riot grrrls evoke a lot of sweet things like candy bars, cinnamon buns, strawberries, and cherry tomatoes. And the further you go into the materials, the more puns and folklore come out. With the

Zeppelin Alchemy Film the cucumber comes from the urban legend that Robert Plant used to “pack” a cucumber to further his sex appeal while performing. These types of things are all embedded in the films entirely through their materials.

QL: Sometimes when I read your titles, with their litany of products—from the hardboiled eggs, lemons, avocados, pickles, milk, and apples of 2008’s

Daisies Roll Up Film to the Diet Coke, Bud Light, whiskey, Epsom salts, Arnica, and Advil of 2010’s

Shred the Gnar Full Moon Film Noir—I think of all those 16th- and 17th-century Flemish still lifes, their tables bedecked and spilling with glassy-eyed fish, grapes, skulls, writing quills. Is this a conscious reference on your part?

JW: I’ve thought about the Dutch and Flemish still lifes a lot, particularly the ones where things are decaying and everything’s knocked over. Immediately prior to making my first “cameraless” film by physically distressing the surface, I was making films shot on 16mm and video, shooting images of everyday objects and materials. I may in fact go back to an early piece, which featured 16mm images of lettuce, tubes, tape, ice, lemons, balls, baking soda, and vinegar, and “treat it” with its own pictured materials—a film version of “you are what you eat.”

QL: It’s interesting—though the titles of those early Northern European still lifes often contained the subjects of their work, as your films’ titles do, your process and product is the exact opposite of those painters’, whose various “materials” never touched their canvases, even though their image ultimately did. On your canvas—film—the materials are all over; they are actually employed as “materials,” yet their “image” has mostly been obliterated. It only exists in the viewer’s imagination, as opposed to the artist’s. Is this tension between the narrative of your titles and the abstraction of your works—between abstraction and representation in general—something you try to enhance?

Installation View of “Perspectives 171: Jennifer West,” Contemporary Art Museum, Houston, 2010. From left: Lavender Mist Film/Pollock Film 1 (70mm film leader rubbed with Jimson Weed Trumpet flowers, spraypainted, dripped and splattered with nail polish, sprayed with lavender mist air freshener), 2009. 46 sec. Shred the Gnar Full Moon Film Noir (35mm film print and negative shredded and stomped on by a bunch of Snowboarders and a few Skiers getting ginormous catching air during Aspen Big Air Competition and Fallen Friends Event– marked up with blue course dye – sprayed with Diet Coke, Bud Lite & Whiskey – taken hot tubbing with Epsom salts, rubbed with Arnica, K-Y Jelly, butter and Advil – full moon shot by Peter West) 2010. 5 min, 9 sec. Photo: Rick Gardner.

JW: I purposely show my cameraless films with my imagistic films in groupings that do enhance this movement between “abstraction”—entirely cameraless films—and imagistic works. And you’re absolutely right that it’s a similar approach to using objects and materials together. But, of course, as you say, not everything is “pictured” as an image and the viewer accesses the “reading” of the piece in a number of very different ways. First off, there’s the reading of the very long title captions and then there is the experience of viewing the film. Even in my films with recognizable images, the viewer is shifting back and forth between an occasional glimpse of imagery and all types of markings, splatters, shred marks, drips, and holes. The images are often partially obscured, and the viewer is moving between the visual experience of the image and that of reading. The space I am interested in enhancing exists between those two experiences. Some things I put on the films don’t do anything to the film itself and aren’t evidenced with any trace at all—hence existing only in the viewer’s imagination. In the beginning, all the films were cameraless, but as I worked through ideas and experimented with the possibilities of the medium, I got interested in seeing what would happen if I mixed abstract mark making over images.

QL: How did you first land on your method of naming your works?

JW: The first film I made, in 2004 and 2005, a cameraless film called

Marinated Film—the Roll of 16mm That I Had in the Fridge for Over 10 Years, had an accompanying work shown on the wall next to the film projection.

Fourteen Recipe Cards: For the Marinated Film was a series of index cards featuring each “marinade” that I used for the film written in pencil. I even smeared them with the materials: wine, Pop Rocks, gasoline, urine, hair dye, blueberries.Later, I showed a few photos made from the

Marinated Film negative in a group show, framed the accompanying index recipe card and hung it, and I remember a friend said to me: “Lose the card.” I told him I wanted to convey this other information to the viewer or the work didn’t make sense to me. With the next round of films I made, I started to incorporate all the actions and materials taken to the film emulsion into the title of each film in parentheses as a long list. These lists got more and more elaborate as more people performed “in” (their image on film) and “on” (doing actions to the film like riding a motorcycle over it) them.

Jennifer West, Nirvana Alchemy Film, (16 mm black & white film soaked in lithium mineral hot springs, pennyroyal tea, doused in mud, sopped in bleach, cherry antacid and laxatives – jumping by Finn West & Jwest), 2007. 2 min, 51 sec.

QL: How did you first begin making films? Who were your early influences?

JW: I think I’m a classic example of someone who has experienced firsthand both analog and digital formats of photography and filmmaking. This has been a huge influence on why and how I make the work I do now: I understand the physical alchemical nature of film and I understand the power of nonlinear video-editing programs that allow for people to produce their own work.

I first made photographs at a very young age in school. I made my first 16mm films in college before I ever made a video. I was very into structural film, particularly Hollis Frampton and Michael Snow, but I was most interested in how Tony Conrad and Carolee Schneemann used film in a physical way. Conrad for his conceptual bent and sense of humor—throwing, pickling, and electrocuting film—and Schneemann’s hand-working her emulsion of sexual images in

Fuses. Rei Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçons “fragrance notes”—which include things like burnt rubber, dust on a hot lightbulb, nail polish, lettuce juice, and sand dunes—inspired several films, as well as my thinking on how to evoke a sense of place through a list of smells. I was also simultaneously intrigued with a number of other artists for their use of materials: Ed Ruscha’s use of beet juice, maple syrup, and Pepto-Bismol in his “liquid word” paintings; Liz Larner’s “culture” works are still some of my favorite artworks ever made; Allan Kaprow’s happenings, for their materials and communal experience; and Barry Le Va’s early felt, glass, and ball pieces.

From left: Tony Conrad’s jars of pickled film, 1974. Photos: Andrew Lampert. Still from Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses, 1965. 16mm film, 18 min.

QL: Can you talk about your “restaging” pieces a bit, from the Allan Kaprow happenings to Pollock’s process for the 1950 painting

Lavender Mist to the 1966 Czech New Wave film classic

Daisies?

JW: Each “restaging” work has differed in its initial impetus. I finished a new work the other week that’s not an artwork per se but a restaging of an earlier work: Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore’s “Love” dress (from

The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects), which has become an LOL dress.Hence the “extension of skin” in clothing now reads with the extension of texting or emailing which has created an entirely new language. What’s great is that many people interpret “lol” as “lots of laughs” rather than “laugh out loud”—someone else told me they thought it was “lots of love.”

But I started the restaging works in a similar way to, say, the music films or even the perfume films: there was something that I wanted to highlight or comparisons I wanted to draw from something in the past. In 2008 I was thinking about what materials, smells, or actions were evoked in films or books. In Věra Chytilová’s film

Daisies, foods play a huge part as symbols, puns, metaphors. A number of phallic foods—pickles, sausages, bananas—are constantly eaten or cut up.The entire film revolves around eating and food fights; from this I chose two scenes to remake. One macabre scene that fascinates me is where the two main characters, both named Marie, cut up each other’s body parts as well as their own—laughing all the while. I wanted to see how I could translate this to film, literally cutting my own filmed images (played by myself and my assistant, Mariah Csepanyi) with a razor blade.

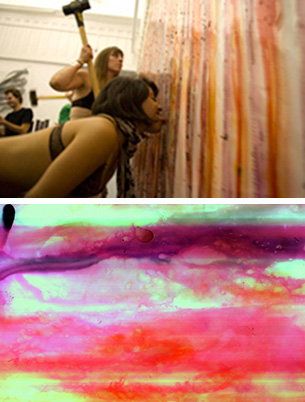

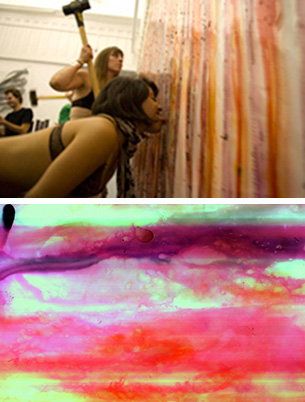

Jennifer West, production still (top) and film still from Jam Licking & Sledgehammered Film (70MM Film Leader Covered in Strawberry Jam, Grape Jelly and Orange Marmalade – licked and sledgehammered by Jim Shaw, Marnie Weber, Mariah Csepanyi, Bill Parks, Alex Johns, Karen Liebowitz, Roxana Eslamieh, Chaney Trotter & Jwest- (a filmic restaging of moments from Allan Kaprow’s ‘Household’), 2008. 3 min, 17 sec.

I remade Kaprow’s Household—intrigued by the iconic photograph of women licking tons of jam off the hood of a car.When I later saw the black-and-white film of the original staging of Household it showed a huge group of young men and women who take their shirts off in liberation, then the men covered a car entirely in jam and the women licked it off. I restaged the happening as a performance of 70mm clear film leader covered in jam, jelly, and marmalade, with shirtless men and women both licking and sledge-hammering the film. The production stills give this larger story of everyone licking the film but, in the end, the film itself looks like a licked sunset—the leader dyed with shades of orange, red, and purple—so there is tension between the very elaborate and specific way in which it was made and the trace that is left.

I made

Lavender Mist Film/Pollock Film 1 in reaction to a lot of people reading my work through action painting, painting in general, and specifically Pollock. It’s true that one of the ways I make markings on my films is by taping the filmstrips themselves to a ground cloth on the floor of my studio, and that I have many devices that I use to splatter, spray, drip, and mark onto the film surface. I wanted to combine materials that I thought would have “gender tension”—hence, I decided to use spray paint and nail polish in the colors that were used on the iconic

Lavender Mist painting. (The nail polish is homage to my mom, who made nail polish drawings in the seventies.) I rubbed the film with jimsonweed trumpet flowers, which grow in the West as a weed, as a nod to the landscape of the Southwest, where Pollock spent time, whilst suggesting a transformation to another state of mind—since the flowers are highly hallucinogenic.

QL: That “gender tension” you just mentioned in regard to your Pollock film makes me think of something else: the relationship between drawing and performance, which always seems to figure quite prominently in feminist art. Is this relationship something you think about in terms of your own process?

JW: The fact that it does figure prominently interests me, and perhaps there is a future film in that. My project did not start out with an emphasis on performance or drawing, although I had been making performative pieces prior to it, but as it progressed it led to many pieces in which performative acts are foregrounded either on camera or upon the film emulsion. The performances have also become more involved with larger groups and with people I don’t know. And, in some of the cases, I am very aware of gender signification. Sometimes this is played out in the production stills—like, how does it look for a woman artist to be squirting chocolate sauce and blowing up film.

I use so many types of mark making on my films, everything from drips, puncturing, writing; lots of bodily stuff like licking, kissing, jumping, rolling, and biting; as well as the skating, driving on, et cetera. There are certain films that aesthetically resemble drawings but, in one, the drawing is made with a hole puncher, in another it’s film rotted by urine, in another, film is decomposed in energy drinks, or it’s film outlined with cinnamon—so in these cases I think the tension is there. Or even in the skating or snowboarding films, in which the markings are made with skateboard wheels and snowboards, all the while making sure there are girls performing in both.

Jennifer West pouring soy milk onto filmstrips, 2010. Photo: Finn West.

QL: How important to you is the publication of your production stills—which reveal your process in all its comic glory and weird beauty: film being fried with some eggs in a pan, soaking in hot springs with some naked bodies?

JW: The production stills are the place where my sense of humor is the most obvious, although I hope this also comes through at times in the titles. It was great when I played a slideshow of production stills during my talk at the Tate, and there was a kid there from Belgium who spoke only French and was laughing hysterically.In addition to the humor, the production stills create a third place of consideration for the viewer: after seeing the film and its traces, and reading the title, you have the still, which foregrounds the over-the-top processes with which the film has been treated. I think a lot about how I know art through photographs, through videos and films of performances, or perhaps in person, through reading and documentation of the artist—so the stills play off all of those things. Lastly, they are often made into ’zines that I give away at my solo shows or larger exhibitions, and this is a very conscious choice to embody the original spirit of self-production that the ’zine has, a generosity toward the viewer—and to embody the spirit of the Pacific Northwest.

QL: It’s interesting that unlike many West Coast and California-based artists, you were actually born here. As the place of your birth, how do you think California generally—and Topanga Canyon’s romantic countercultural mythology specifically—influenced your work?

JW: I lived in Topanga until I was 12; then in Denver, Colorado; and finally on Capitol Hill in Seattle. I’m a hodgepodge of cultures and cities; and the Pacific Northwest, and my time in Seattle and Olympia, Washington, had even more of an impact on who I am, since I came of age there. But I think moving away from Topanga to experience these very different small cities made me much more aware of what was different about Topanga, but also what it was missing: the grit, grime, and underbelly of a city, of the collision of cultures. So it was enlightening to move away. And it’s this comparison that often propels me back to nude beaches, communal living, activism as well as attitudes toward nudity, natural foods, cussing, drugs, communal experience, sexuality, breaking rules, and a general disregard—irreverence—for proper social conventions. The landscape, cultural lifestyle and subcultures of not only Topanga but all of California and the entire West Coast often come into play in my work: road tripping, fires, beach, desert.

I think Topanga also made me hyperaware of things like gated housing communities, suburbia, and mass-produced culture, and these themes come up in my work. For example, I made a film that was sprayed with both Axe Body Spray and patchouli—two smells that say something about who you are when you wear them.

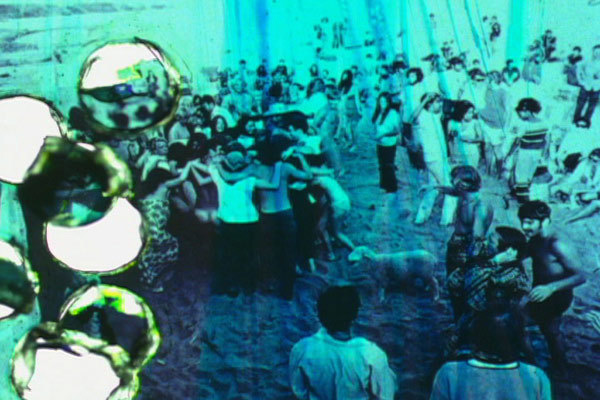

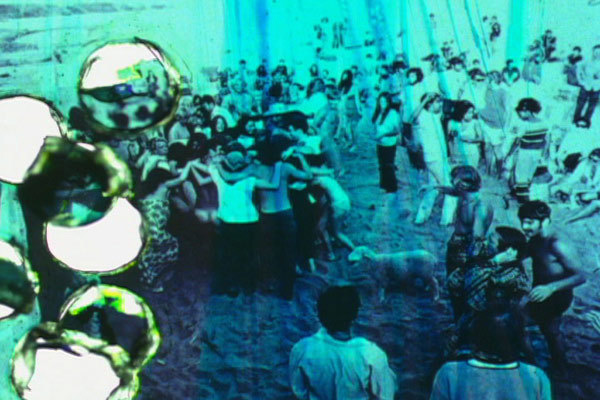

Jennifer West, Topanga Beach Houses Imminent Domain Rewind Film (16mm film print rubbed with aloe vera gel, smeared with Sex Wax surfboard wax, butter, grass, hole punched – still photos of the Topanga Beach community in the 1960’s and 70’s before the houses were bulldozed and burned with the Imminent Domain Law – movie stills from “Muscle Beach” and “Cosmic Children” – found photographs from the Int’l Surfing Magazine (Jim Fitzpatrick), Malibu Times (Gary Graham), Marlies Armand, Jeff Ort, Woody Stuart and John Clemmens), 2010. 2 min, 47 sec.

QL: It’s striking to me that so much of the art—writing, film, visual art, pop music—made about Southern California has been made by people who are not originally from here. Often our understanding of it comes from recent recruits. How do you think being from California—as opposed to making the storied pilgrimage and starting a life here—has influenced your understanding of its Edenic myths and more concrete realities?

JW: All that I know is from when I was a kid, so I come back to it perhaps to expose or examine certain things that I thought or imagined but never knew as an adult. Since I’m fourth-generation Californian, I do, however, know a lot of specific details of its history, and that’s what sometimes gets me involved in a project. For example, my dad told me about how Disneyland used to have a dress code and didn’t allow anyone to visit who had sideburns in the 1970s, and that’s how I became interested in researching the history of protests and rebellion at Disneyland.Also, both sets of my great-grandparents lived in Santa Barbara at the turn of the century and in Los Angeles in the fifties. I have war-ration books from World War II that my grandmother saved and a lot of stories from the

Los Angeles Times, where my grandfather worked, like about the Manson family girls with their shaved heads and X’s marked into their foreheads. I heard things from my mom about when she attended her first happening at UCLA or the first meeting of what became Womanhouse. And stories about my parents drag racing in the 1950s in the LA River.

QL: What do you see as the relationship of your work to LA’s film industry, or how has the industry influenced your thoughts about film? It’s notable that the tradition of experimental film that you are continuing was more based on the East Coast than in California, where popular narrative has long ruled.

Jennifer West, filmstrip from Regressive Squirty Sauce Film (16mm film leader squirted and dripped with chocolate sauce, ketchup, mayonnaise & apple juice), 2007. 3 min, 36 sec.

JW: I don’t think I would be making the work I make if I lived anywhere else. Or I should say I don’t think my work would have developed in certain directions were there not an interaction with certain aspects of the picture industry here. I use a lot of cast-off materials from the industry—short ends from Hollywood film shoots, free recycled editing materials from labs—and then reinsert the films physically back through their machines in the telecine process. On the one hand, I am a prankster: putting film that has been covered in vodka, butter, aspirin, weed, Viagra, you name it, through the telecine machines. But many of the technicians and vendors take great pleasure in working with me; both film-nerd types who revel in how I expose the material layers in film emulsion, to the colorist telecine operators who find relief in doing something so drastically different from, say, Top Model or Gossip Girl.

It’s the personal relationships that I have forged in the industry that allow me to do what I do. I have a telecine colorist who sneaks in all my gunk-covered 16mm and 35mm film—letting me put it through the machines and not only laughing amused (“what did you do to the film this time?) but being highly interested in the aesthetics of the films.

I also have a special relationship with a 70mm lab in town: They have given me all the film stock and leader that I use to make my work, and they think that I am the “only one in the world doing this.” They somehow have no idea about Len Lye, Stan Brakhage, et cetera.

Regarding East Coast experimental film: It’s true that the history I am building from comes mostly from the East Coast in the sixties, though it connects to an older history of Lye, Man Ray, Norman McClaren, and Dieter Roth. However, the “structural filmmakers” Ernie Gehr and Morgan Fisher are based in California and, of course, the West Coast has a rich tradition of experimental filmmakers in general, with Canyon Cinema and Bruce Conner, Chick Strand, Jordan Belson. Oskar Fischinger made films in LA in the thirties and Maya Deren made Meshes of the Afternoon here in the forties. My “trespassing” in Hollywood suits what my work is, and it’s important that it is folded back into Hollywood. Even my work as a teacher at USC serves a similar purpose. The commercial-film students come to take my class so they can “experiment,” and it’s another way that I bring awareness to a whole other way of working—not necessarily what I do but myriad ways of working with the moving image.