The Rise, Fall, and Reinvention of The San Francisco Art Institute

by Margaret Crane

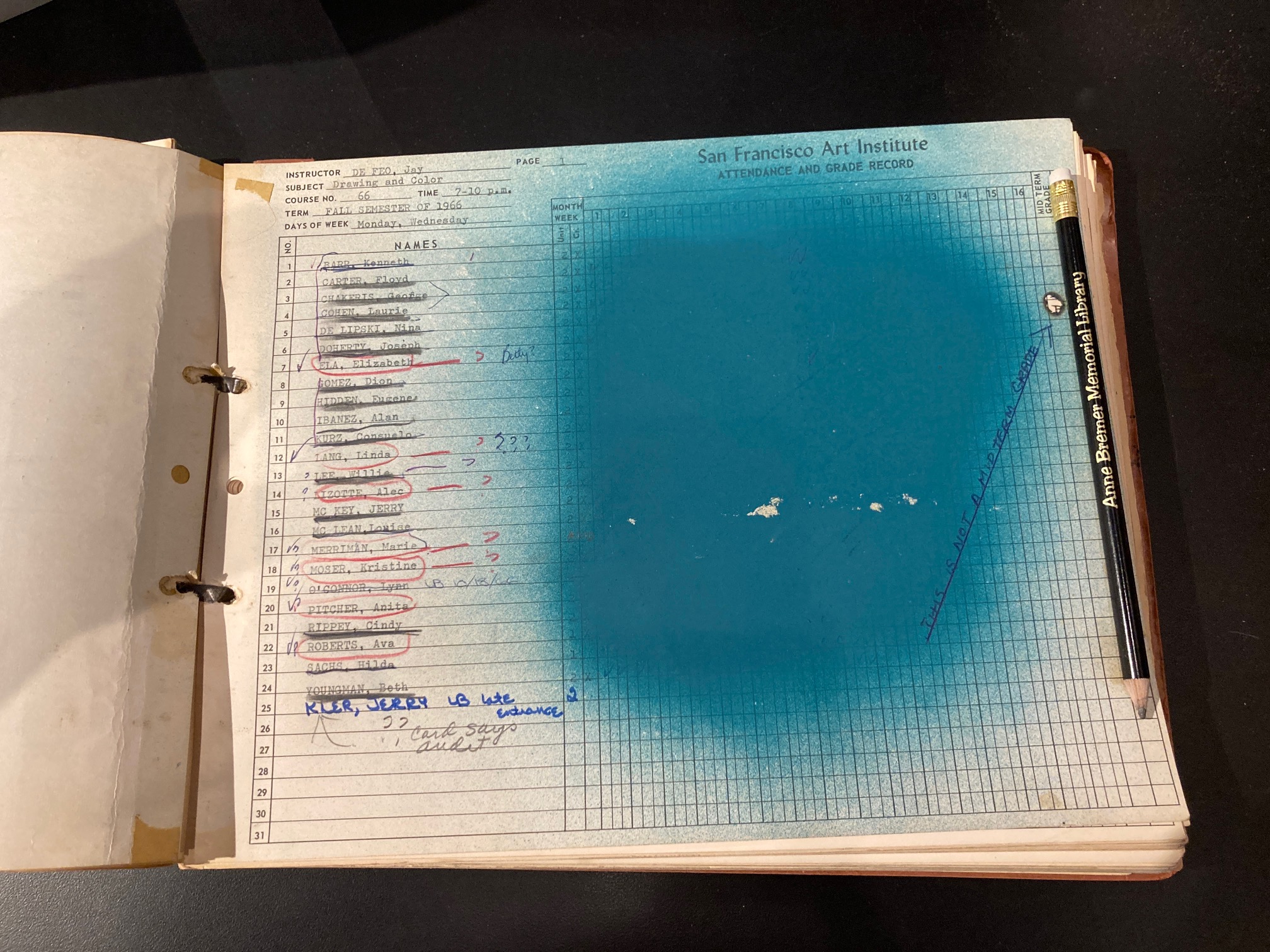

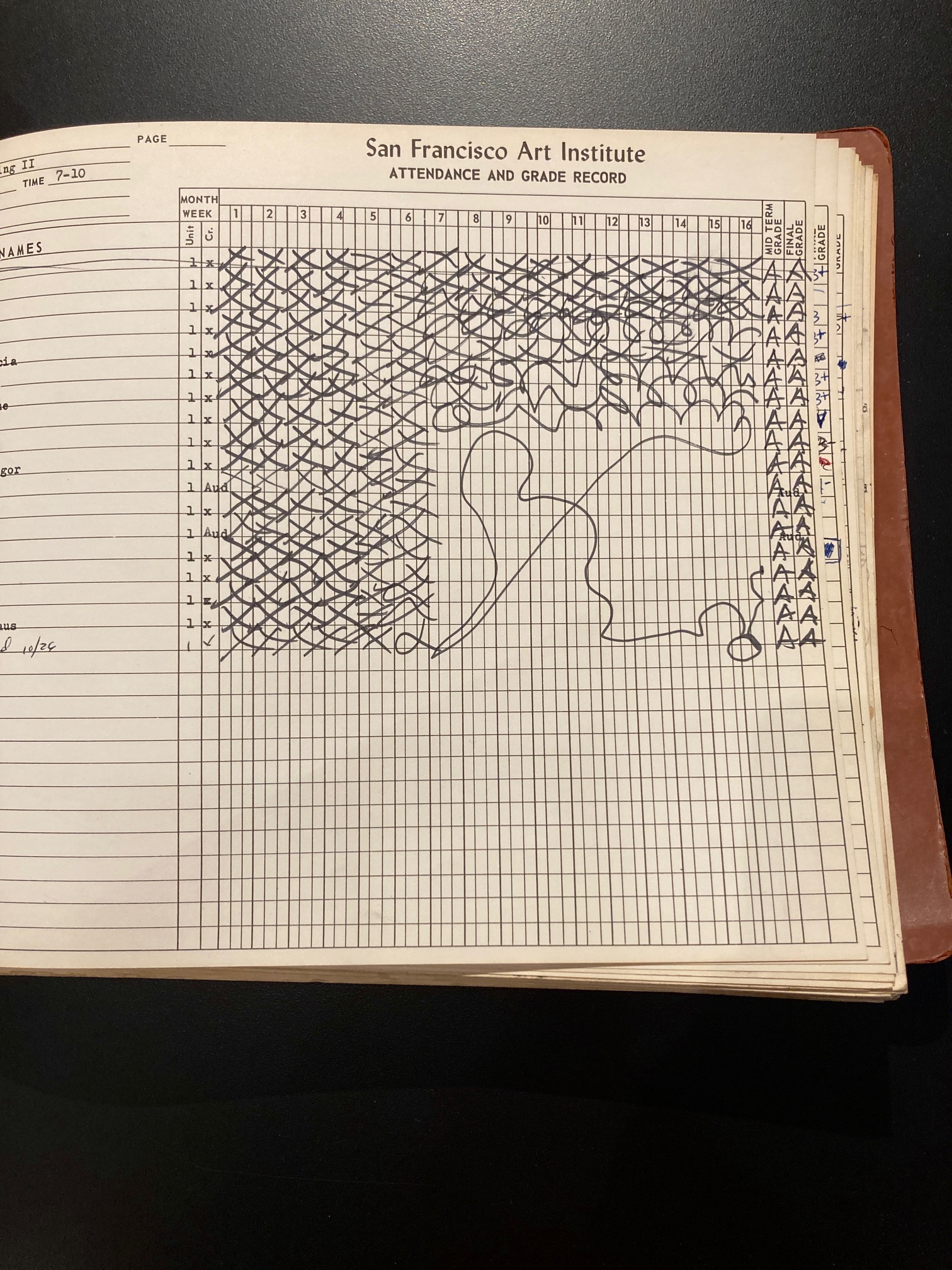

Obliterated attendance records for Jay De Feo’s 1966 Drawing and Color class. Courtesy of San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

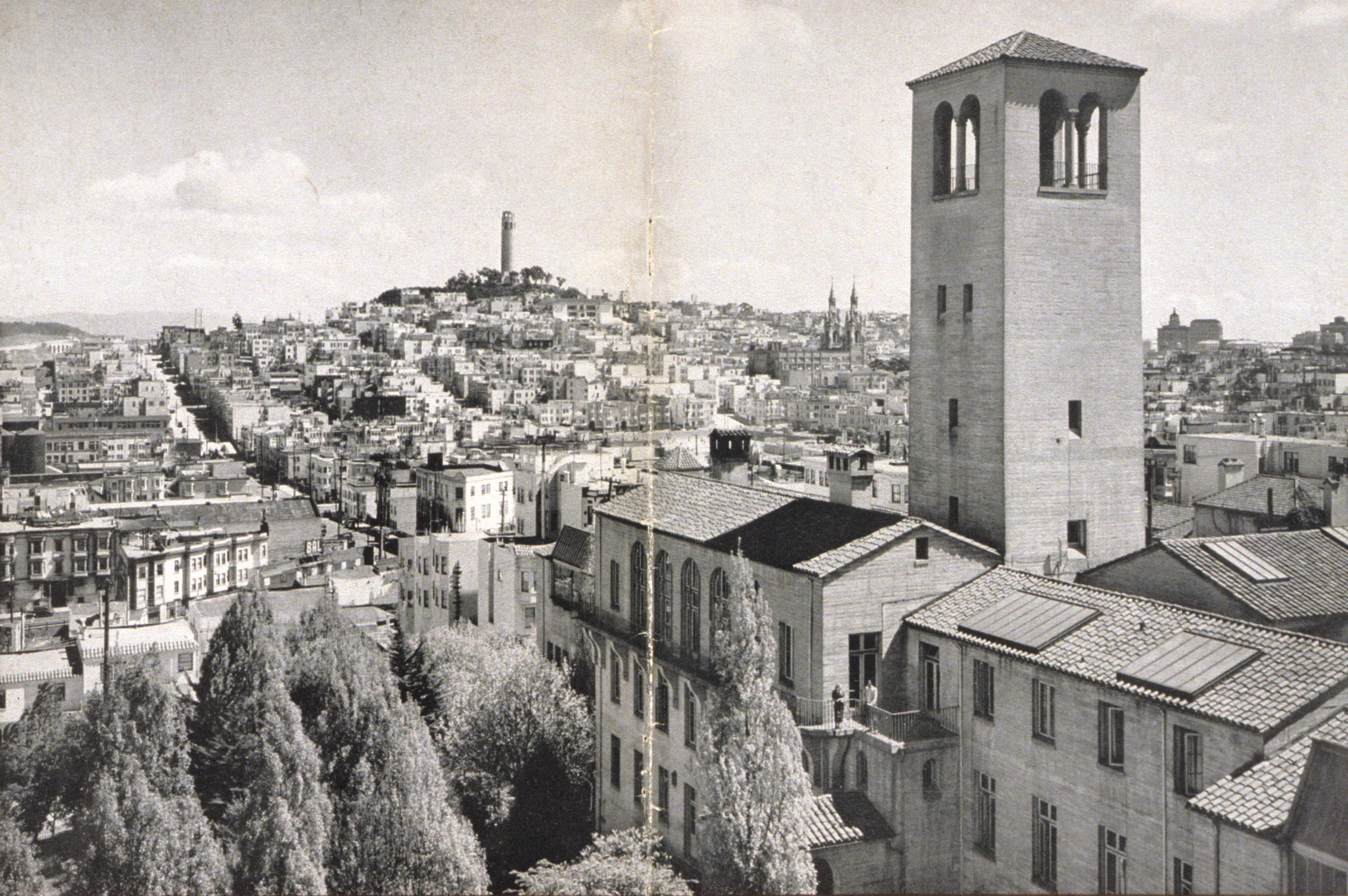

The real estate brochure describes a 94,000-square-foot “specialty building” on San Francisco’s Russian Hill. Potential buyers are invited to consider “one of the largest tracts of private property in San Francisco improved with a pair of structures designated San Francisco Landmark #85.”1 The improvements: a 1925 Spanish Colonial Revival building, complete with bell tower and courtyard, designed by Bakewell and Brown, and Paffard Keatinge-Clay’s 1963 brutalist-style addition. Inside is a 22-by-30-foot fresco painted by Diego Rivera in 1931. The brochure reassures buyers that the monumental work is unlike the Mexican artist’s “other paintings in which he mostly showed his hatred for the rich.”2

Located on the high slope of Chestnut Street since 1926, the former home of the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) looks out over the roofs and steeples of North Beach and across the bay to Alcatraz. Henri Matisse visited the campus in 1931. He commented, “that he had never seen such magnificent lighting and working conditions in Europe.”3Photographer Linda Connor taught at SFAI from 1969 until the school closed in 2022. She recalled the campus, “It was such a privilege to be on that hill, and once you got within the walls, to have those views and that sense of a location in the city.”

“The minute I walked through the archway on Chestnut Street,” said alumna Felicita Norris, “I saw all this amazing art in the courtyard. A chill came over my body and I knew that this was the place where I needed to be.”4

In July 2022, after 152 years, SFAI, the oldest school of fine arts in the Western United States, announced that it would terminate all programs and close its doors. “It just stopped and I, quite frankly, went into mourning,” said Connor. In April 2023, the Institute filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. The building was listed for sale in June of that year.

What remains inside: an empty theater, painting studios, film equipment, and abandoned artworks. The oldest fine art library on the West Coast is still full of books. With sweeping views of the Bay, it is paneled in Craftsman-style woodwork and contains murals by Victor Arnautoff. Scattered throughout the building are the “lost murals”—Depression-era frescos, painted over and obscured for many decades, rediscovered in 2013, and now restored.

Maria Theresa Barbist, President of SFAI’s San Francisco Artists Alumni (SFAA), entered the shuttered building to retrieve student transcripts that had been left behind in the rush to shut down the school. “It was so sad to see trash lying around and it being so empty,” she said. “But the building, the walls, the mural, they hold so much time, so many ghosts and spirits.”

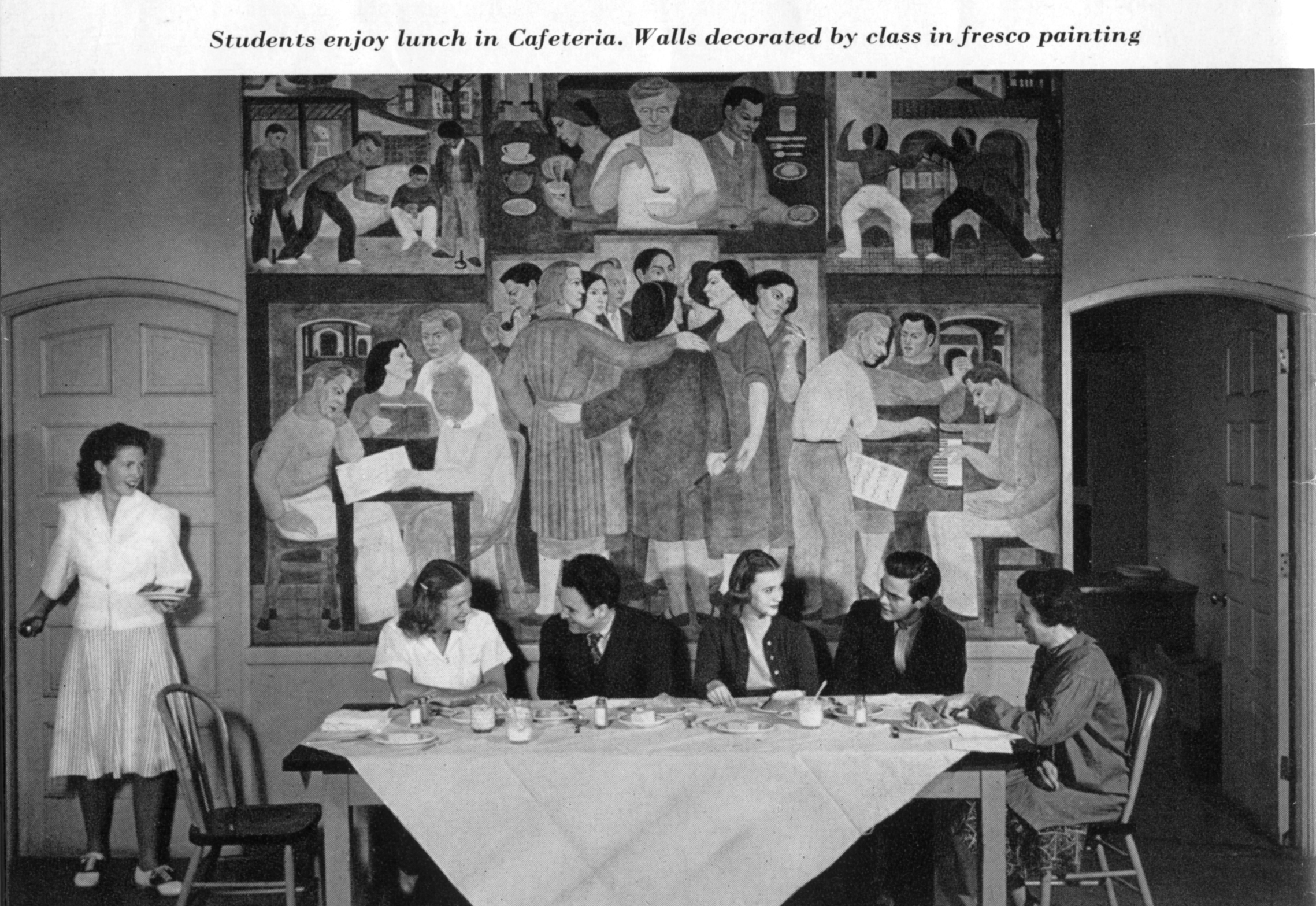

Cafeteria mural by Grace Morton; photo by Ansel Adams c. 1939, from SFAI college catalog. Courtesy of San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

A Storied History

The San Francisco Art Institute was launched as the California School of Design in 1871. The school became known as the California School of Fine Arts in 1916, moved to the Chestnut Street location in 1926, and was renamed the San Francisco Art Institute in 1961.

Throughout its history, SFAI was at the forefront of new ideas and cultural movements. In 1880, the school hosted the first public showing of Eadweard Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope, a precursor of the movie projector. In 1945, Ansel Adams founded the country’s first department of fine art photography. His faculty was a photographic dream team featuring Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, Lisette Model, and Edward Weston, among others. Filipino-American artist Carlos Villa was a pioneer of cross-cultural arts and education. Beginning in the 1970s, his groundbreaking series of exhibitions, symposia, and classes, Worlds in Collision, helped create the movement for inclusion and diversity in the arts.

“It galvanized my consciousness,” said another Filipino-American artist Paul Pfeiffer. Recalling one of Villa’s symposia, the SFAI alumnus noted, “I remember struggling to stay awake in art history classes… but remember feeling riveted at Worlds in Collision. These were people who could be my uncles and aunts talking about art history!”5This sense of generational echoes reverberates in his retrospective, Paul Pfeiffer: Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom, on view at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art from November 2023 through June 2024.

Ansel Adams, San Francisco Art Institute Campus, c. 1939. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

In the years following World War II, SFAI was the West Coast hub for Abstract Expressionism. The Beat Generation coalesced in SFAI’s North Beach neighborhood. In 1955, Allen Ginsberg gave the first public reading of Howl at the Six Gallery, founded by SFAI alumni. During the 1960s, the school was a major source for the Bay Area Figuration and California Funk movements. Faculty and student work reflected the region’s radical politics and counterculture. In the 1970s, SFAI was influential in the emergence of experimental performance and video, and pivotal in the rise of West Coast Conceptualism. LGBTQ students organized the “SFAI Gay and Lesbian Group” in 1988. That year, for the first World AIDS Day, they created a “happening” in San Francisco’s Union Square, complete with beds for lounging and discussion of safe sex practices. In the 1990s and 2000s, artists associated with SFAI—inspired by hobo and folk art, comics, graffiti, and the street culture of San Francisco’s Mission District—were dubbed the Mission School.

“Being a keen observer of culture, of society and unafraid to critique it was definitely part of the ethos,” said Jennifer Rissler, SFAI’s Vice President and Dean of Academic Affairs. “The school called you out and made you rethink your work in relationship to ideas. The questioning of established frames was everywhere.”

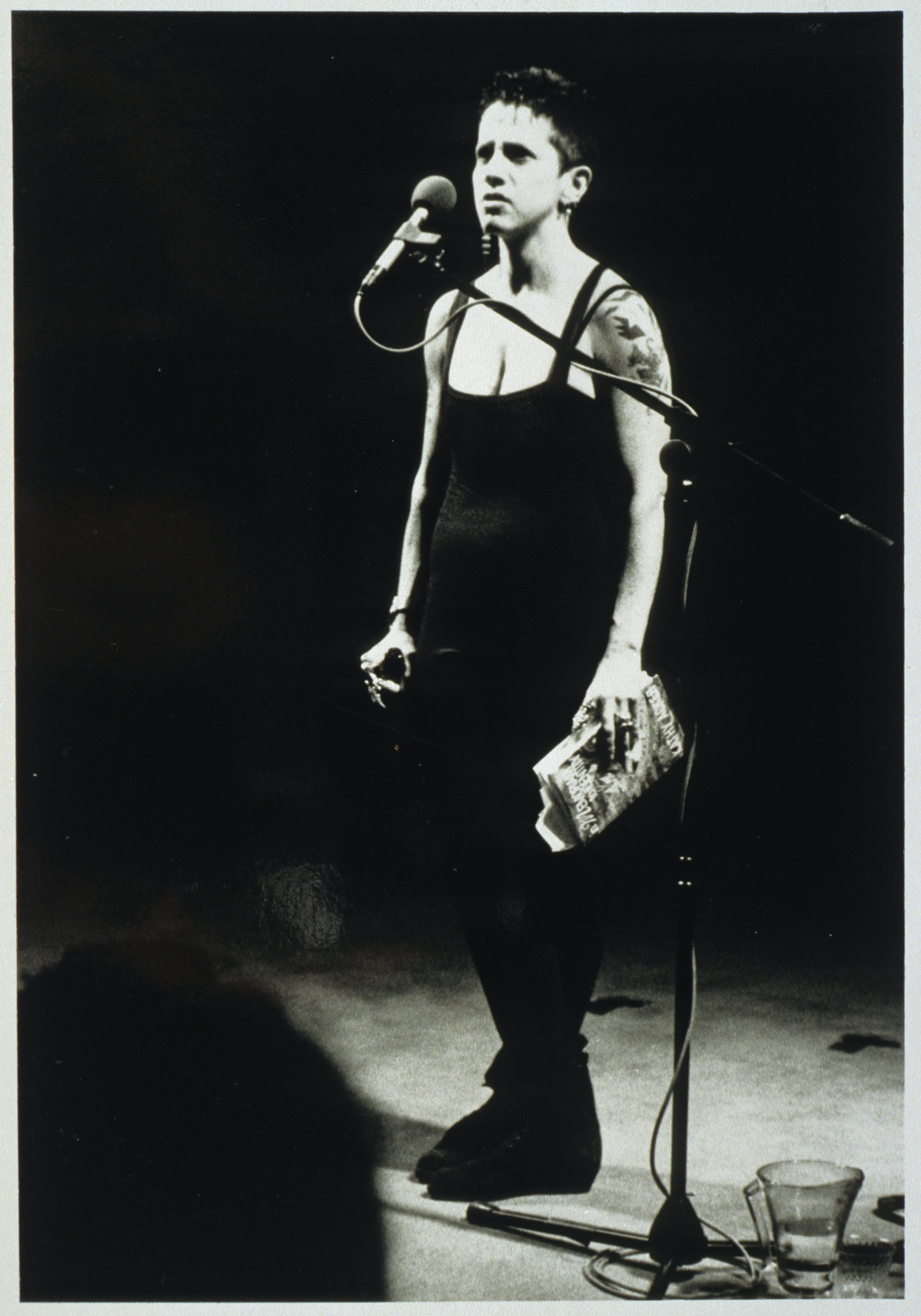

Across disciplines and decades, SFAI’s alumni pursued strikingly individual careers. Some notable examples include Mount Rushmore sculptor Gutzon Borglum; photographers Catherine Opie and Annie Leibowitz; performance provocateur Karen Finley; tattoo innovator Don Ed Hardy; Oscar-winning director Kathryn Bigelow; the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia; and Kehinde Wiley, who painted the official portrait of former President Barack Obama.

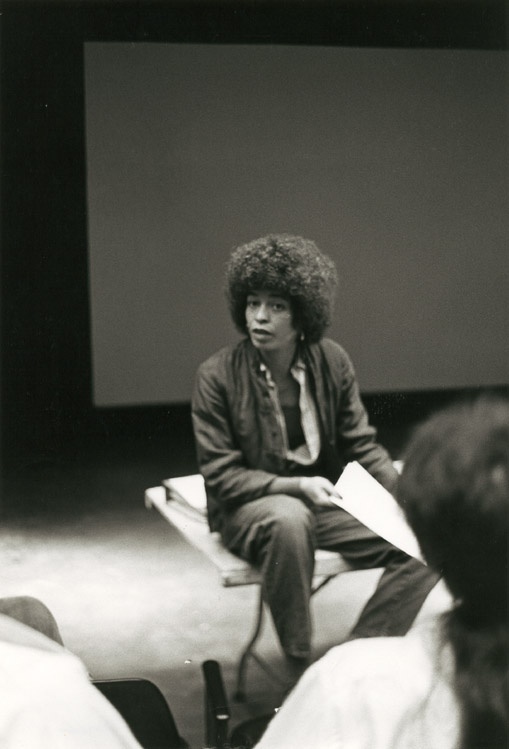

SFAI faculty Angela Davis, c. 1978. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

SFAI faculty Kathy Acker, 1990. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

The faculty were remarkable: painters Richard Diebenkorn and Joan Brown (both also alumni), Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, activist and author Angela Davis, writer Kathy Acker, cultural anthropologist Gregory Bateson, poet Kenneth Rexroth, and underground cinema legends George and Mike Kuchar, to name only a few.6Writer and critic Hilton Als was a visiting faculty member in the last days of the school.

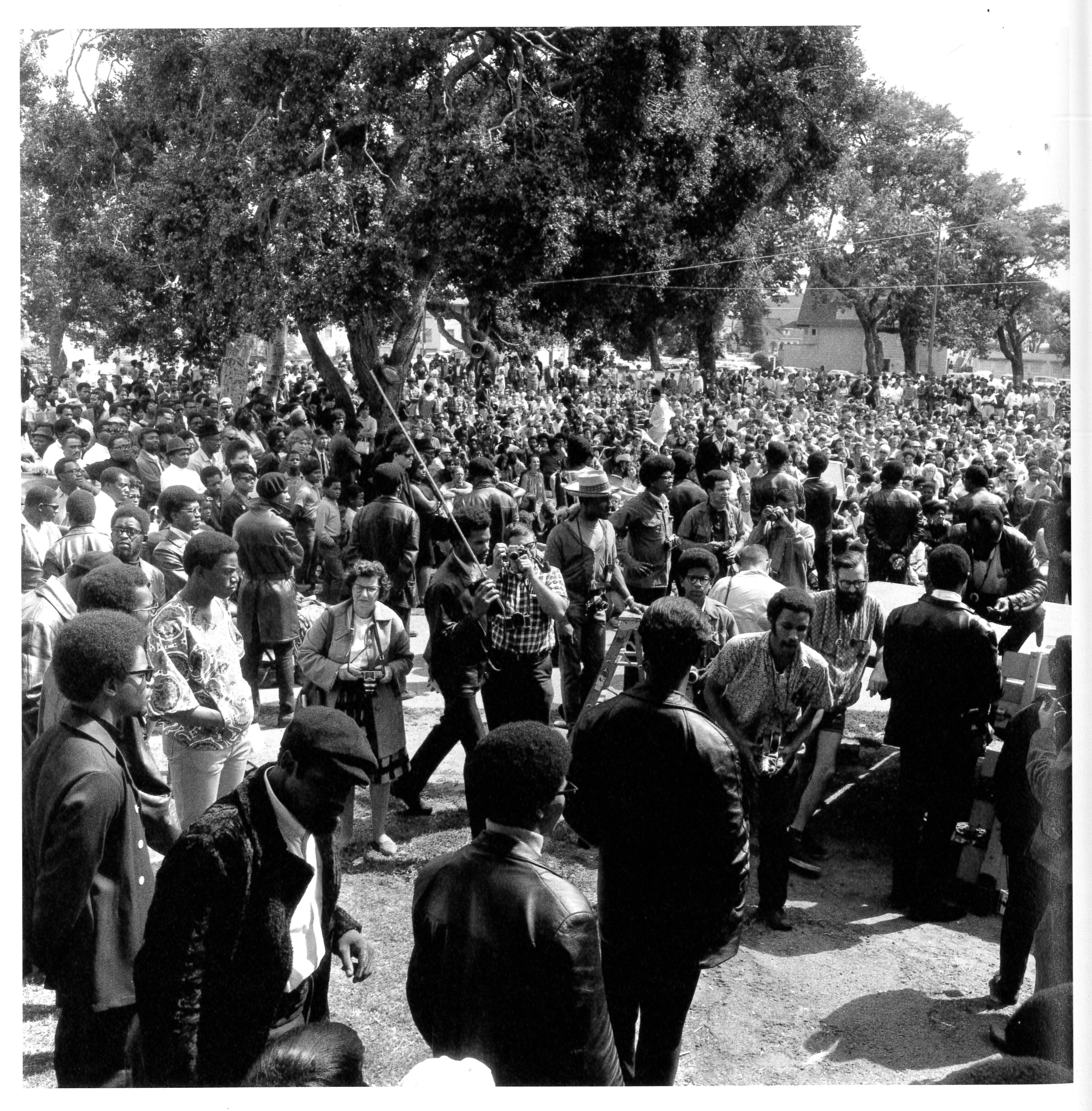

“There’s a lineage from teacher to student, with students going on to become prominent artists and teachers, moving concepts and ideas forward throughout the history of the school,” said Rissler. In the 1940s, Pirkle Jones and Ruth-Marion Baruch were among the first students in Ansel Adams’ photography department. Among their notable projects, Jones documented Sausalito houseboat dwellers, and Baruch the hippies of Haight Ashbury. Together, they created a photographic study of the Black Panther Party at the height of its activism.

Video, performance, and “second generation” conceptual artist Tony Labat studied at SFAI with Bay Area Conceptualists Paul Kos, Howard Fried, and others. He taught in SFAI’s Performance Video/New Genres department for 37 years. “The Art Institute wasn’t a bubble,” he said. “It was the city. All the changes, the constant revolutions that happened there—the gay community, the Chicano community, you name it—the school was part of that. It was the place to talk about what was going on.”

In 2020, the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) and SFAI’s archive collaborated on the online exhibition Orbits of Known and Unknown Objects: SFAI Histories. Celebrating SFAI’s 150th anniversary, the exhibition highlights connections between these significant objects and the people, places, and movements of the Bay Area art scene.7

Pirkle Jones, Ruth Marion Baruch at Black Panther rally, 1968. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

The Downfall

Given the school’s extraordinary history, what led to its demise? Some cite the ineffectual leadership of SFAI’s presidents over the last 20 years. Others blame the Board of Trustees. Most agree that constructing a costly new studio complex at San Francisco’s Fort Mason was, in retrospect, a bad idea. Enrollment fell off. Communication deteriorated. The Bay Area is expensive. Covid didn’t help.

Deborah Obalil, President and Executive Director of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design (AICAD), put it this way, “The San Francisco Art Institute was a unique option for students who wanted a small, focused, community-driven type of educational environment that is increasingly difficult to find. Unfortunately, the current financial realities of higher education have started to squeeze out small and specialized institutions.”

“We were true to being a fine art conceptual school,” said Rissler. “You went to SFAI because you wanted to be an artist. It wasn’t applied art. That was a risk that we took.”

SFAI students at NASA Zero Gravity Tests KC-135 turbojet in Houston, 2001. Students also visited NASA in 1999 and 2004. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

The future appeared bright in 2017 when SFAI opened the new $14 million campus expansion on a pier at Fort Mason, but almost immediately, enrollment declined. Within two years, a fundraising campaign for the new campus foundered, leaving the school $19 million in debt and precipitating a slow-rolling financial crisis. The Russian Hill property, and all other assets of the school, became collateral for a loan to secure the debt. According to the terms of the loan, Boston Private Bank was entitled to foreclose if the school’s endowment fell below $2 million.

“We realized that we had to raise $5 million right away,” said board member Jeremy Stone. “There was no money for paying the faculty, no money for the staff. We started dialing for dollars every day and raised $6 million. We got the school to stay open a few months longer.”

In March 2020, Covid lockdown began. SFAI suspended in-person classes and degree programs and laid off adjunct faculty. In July, Boston Private moved to foreclose on the loan.

In the first days of 2021, “a group of board members convinced the University of California Board of Regents to buy the note from Boston Private,” said Board Vice President John Marx. “They literally closed on the deal the day before the bank sent the sheriff over to seal the campus.”

Later that year, SFAI launched its 150th anniversary celebrations with an exhibition: The Spirit of Disruption. The board joined forces with high-profile alumni artists to stage the successful Looking Forward benefit auction in November. The proceeds, along with donations and budget cuts, allowed the school to resume fall classes, but by then, many students had scattered.

“We were seeing this beautiful thing dying right in front of us,” said alumnus Lexygius Sanchez Calip.

In May 2022, SFAI held its last commencement. In July, on-again off-again negotiations to merge with the University of San Francisco, a private Jesuit university, were terminated by the university. With that lifeline severed, the Board of Trustees issued a letter announcing, “SFAI is no longer financially viable and has ceased its degree programs.”

“There was a level of vision that could have moved the school into the future. This was achievable, but without any kind of financial infrastructure, we were absorbed in managing the USF merger and keeping creditors at bay,” said Lonnie Graham, the last President of SFAI’s board.

In April 2023, the San Francisco Art Institute declared Chapter 7 bankruptcy, which required the liquidation of the school’s assets to satisfy creditors.

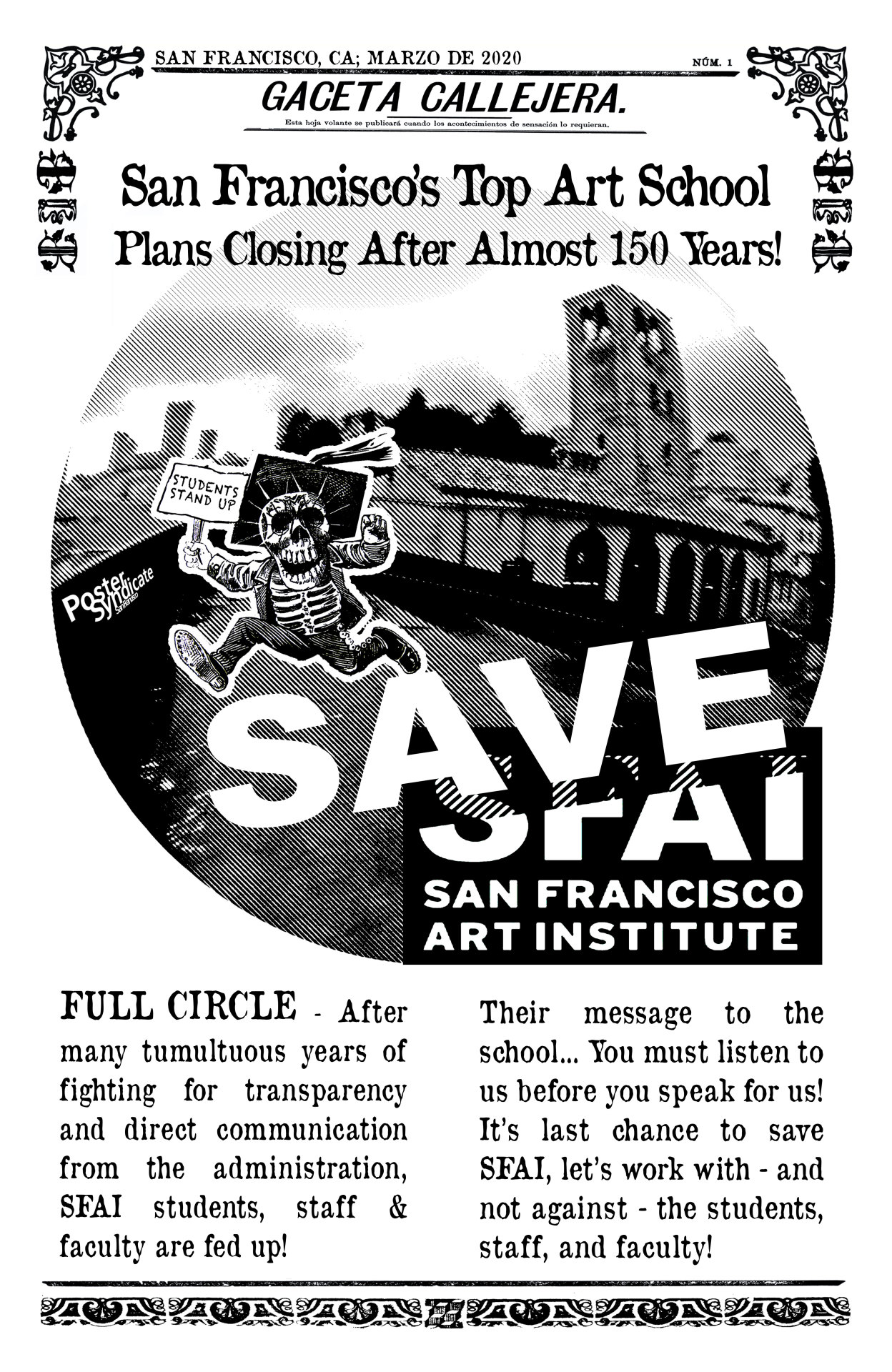

Michelle Williams, Save SFAI, San Francisco Poster Syndicate, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Diego Rivera, Making of a Fresco, Showing the Building of a City, 1931, Diego Rivera Gallery, San Francisco Art Institute. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

The Rivera Mural

Diego Rivera’s monumental painting, The Making of a Fresco, Showing the Building of a City, could be viewed by all who came to the Chestnut Street campus. Rumors of its possible sale ignited a firestorm within the SFAI community and the greater art world. The mural was widely reported to be valued at $50 million. Its cultural value is incalculable.

Divided by a grid of trompe-l’œil wooden scaffolding, the Mexican artist’s fresco is a painting-within-a-painting, simultaneously depicting the construction of a modern metropolis and the creation of the mural itself. It is populated by a cast of characters—assistants, engineers, industrial workers, and art patrons—many of whom are portraits of people involved in the project. Rivera himself appears sitting on the scaffold, his back to the viewer, holding a paintbrush and palette.

In December 2020, a letter to staff and faculty disclosed that “the Board voted, as part of their fiduciary duty… to explore pathways and offers for endowing or selling” the mural.8Controversy erupted over whether the ultimate goal was to sell the mural outright and have it removed by the purchaser (a risky, if not impossible, endeavor) or have it endowed in place, with its gallery as a dedicated exhibition space.

Board members contend that they were obligated to investigate all options for stabilizing the school’s finances. In conversations, several cited confidential negotiations with possible benefactors and asserted that their ultimate intent was to endow the mural in place. Other SFAI stakeholders believe otherwise.

In January 2021, a tipster contacted The New York Times about a possible sale to film director George Lucas, who was in the process of developing his Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles.9Board member Jeremy Stone asserts that the idea was to establish a “George Lucas Museum on campus” and noted, “Lucas engaged in negotiations under the agreement of complete privacy and secrecy, and backed out the minute the press came out.”

Emotions ran high as the news of plans to monetize the mural emerged. Artist and former faculty member Mildred Howard circulated a petition, signed by artists and art leaders across the country, supporting the mural’s sale, if necessary to save the school. In an open letter, alumni photographer Catherine Opie referred to a sale as “an unconscionable decision” and withdrew her work from the upcoming benefit auction.10SFAI’s Adjunct Faculty Union (SEIU Local 1021) also issued a letter: “Rather than assume fiscal responsibility for (their) failures, the board attempts to conceal them from the public by translating the school’s most important cultural artifact into a monetary instrument.”11

“Should we sell it? Should we not sell it? It was splitting the community in half,” recalled the alumni association’s Maria Theresa Barbist.

Aaron Peskin, the San Francisco Supervisor representing North Beach, declared that a possible sale was “a crime against art.”12His resolution to designate the mural as a city landmark was unanimously approved on January 12, 2021. The building itself already had landmark status.

“The unintended consequence,” said SFAI Board Vice President John Marx, “was that we were unable to borrow against the mural. We needed to buy a couple more years, and $20 million would have done that. But we couldn’t borrow against the mural because it was landmarked, and the landmarking thing just spooked the banks.”13

Solutions in the Wake of Chaos

Currently, the red double doors leading from Chestnut Street to SFAI’s courtyard are padlocked, but a vibrant community lives beyond its walls.

“The school’s archive is the historical legacy, and its alumni association is the living legacy,” said Barbist. Formed in its waning days, the SFAI Legacy Foundation and Archive, and San Francisco Artists Alumni now play pivotal roles in the continuing culture of the school.

The school’s alumni association was formed in 2020 to support students and alumni during the isolation of the Covid pandemic and the school’s financial turmoil. Alumni association Vice President Annie Reiniger-Holleb noted, “People were stressed. We had online town halls to facilitate communication with the community, the Board, and the administration. The people who were in power weren’t transparent. We gave everybody a voice.”

The association is now a vital connector for alumni around the world. It organizes monthly Zoom critiques, and online and gallery-based exhibitions. Its comprehensive website hosts a lecture series, podcast, features, and more.14

San Francisco Art Institute Library Reading Room, murals by Victor Arnautoff. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

The archive of the San Francisco Art Institute’s 152-year history chronicles its impact on 19th, 20th, and 21st-century art and culture. Jeff Gunderson and Becky Alexander were the schools’ librarian/archivists. When the school closed in 2020, they packed up 1,000 boxes of material that comprised the collection and moved them to a new location in San Francisco’s South of Market district. Teams of Bay Area librarians pitched in to help. The alumni association’s Reiniger-Holleb compares the archive to “Noah’s Ark.”

In March of that year, the alumni association and veteran San Francisco gallerist and filmmaker Diana Fuller hosted an art auction, The Spirit is Alive, to support the archive. The proceeds helped pay the rent on the new space.

Gunderson and Alexander continue to oversee the archive at its new site. “There was so much support from the community and the alumni,” said Alexander. “As the school was failing, they saw the need to preserve its history and legacy and keep something alive after it closed.”

In the fall of 2022, the archive was officially transferred to the SFAI Legacy Foundation and Archive as an independent non-profit.15

Linda Connor, Protector, knocker on the main entrance of the former San Francisco Art Institute, 2023. Courtesy of the artist. Knocker was probably made in Nepal or India c. 1920s.

What Remains

When you step into the space housing SFAI’s archive, the first thing you see is a wall displaying a selection of artifacts and photos. Among them are a massive wooden sign for the California School of Fine Arts; a photograph of the school’s first location in the Mark Hopkins Mansion on Nob Hill; a large-scale photo of a life drawing class taught by Richard Diebenkorn in 1948; a Spanish tile from the courtyard fountain; and scrawled on a tattered placard, “Give SFAI To The Students.” Another wall is lined with boxes containing material relating to every exhibition from 1871 to 2022. On display are examples from a trove of SFAI-created psychedelic posters, predating the Summer of Love. Passing through the room, you see two iridescent coyotes, part of a pack created for SFAI’s roof by student Germán Benincore in the final days of the school.

The archivists describe the collection as “550 linear feet of archival records, including archival manuscripts, account books, minutes of meetings, photographs, blueprints, broadsides, clipping files, and ephemera, as well as audio and video recordings of public programs, classroom lectures, and other events.” A description of objects from the archive in the Orbits exhibition hints at the presence of “enigmatic objects—known, little known, and unknown—that further intrigue and amuse researchers.”16A Hells Angels style black leather vest proclaiming “Sculpture, Art Institute, Frisco,” on the back;17 and the bronzed Birkenstocks memorializing late dean and longtime teacher Fred Martin are among such wonders.18

The archive sheds light on under-recognized artists such as Japanese American alumni Hisako and Matsusaburo Hibi, who continued painting while confined to internment camps during World War II, and students from the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, who attended SFAI in the 1960s and 1970s, some of whom were active in the Native American occupation of Alcatraz.19

The oldest object in the archive is a record of the first meeting, in 1871, of the San Francisco Art Association (progenitor of both the SFAI and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art). “There’s nothing like primary source stuff,” said archivist Gunderson. “And this is very rich. It’s important to art historians, curators, and people doing exhibitions on artists whose histories relate to Northern California.”

Recently, the archive has hosted scholars from Stanford University, Exeter College, and researchers from the Bay Area and beyond. Alumna and former faculty member J.D. Beltran is working with the archive to explore SFAI’s history and lore for Pay Attention, her novel in progress.

A grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities allows the archivists to rehouse the collection, digitize at-risk audio-visual recordings, and create research guides to make the archive available to a global audience online.20

“There’s a lot I can’t control,” said the archive’s Alexander. “I have to be at peace with that. The worst has already happened. The school closed. We’re doing what we can to preserve this history and get it into great shape for the future. That’s really all we can do.”

Future plans: an archive-based exhibition on Beat Generation epicenter the Six Gallery; film screenings from the archive’s 16mm film collection; and “a series of San Francisco-based walking tours that explore hidden histories of art and culture embedded in the architecture and collective memory of the city.”21

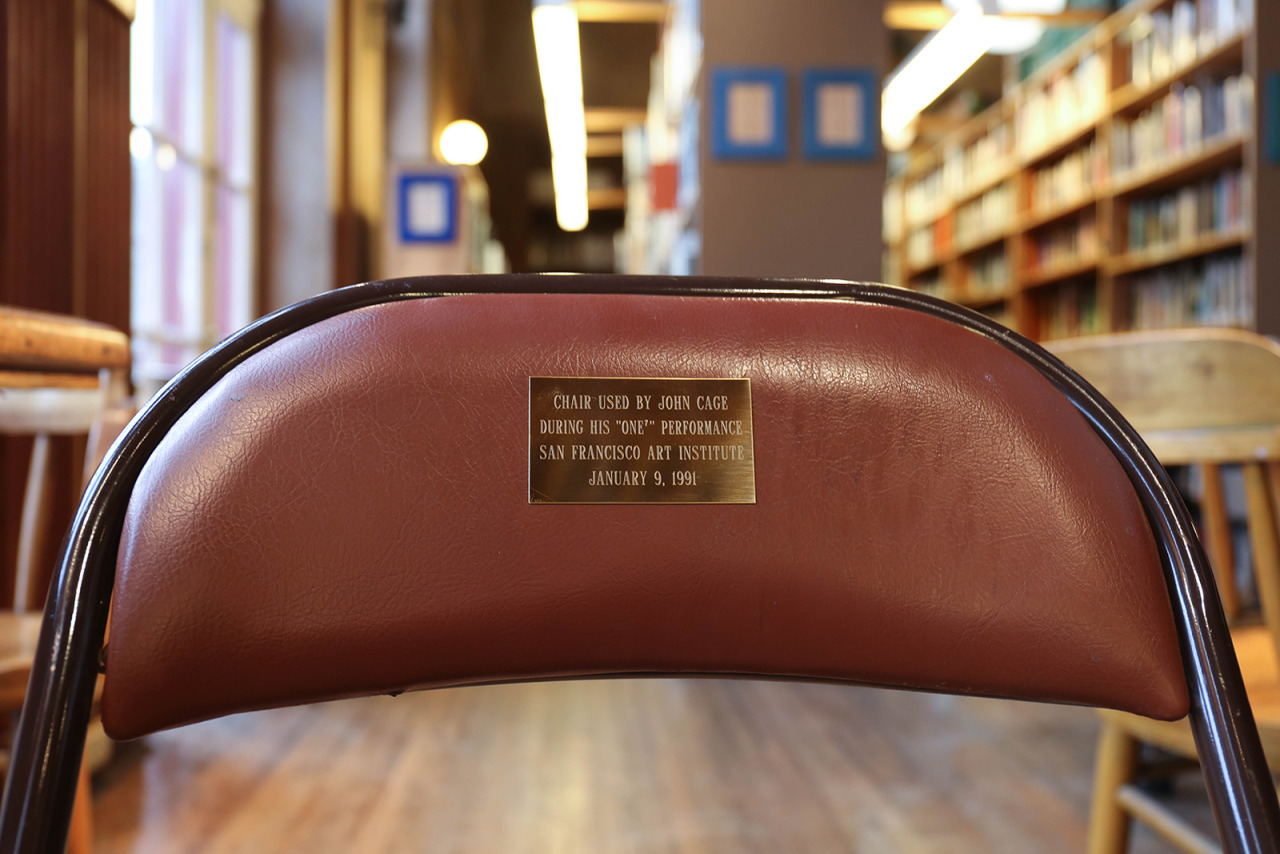

John Cage Chair, 1991, San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

Into the Future

On September 7, 2023, the San Francisco Business Times broke the news. A nonprofit consortium was planning to purchase SFAI’s campus, with the intention to “create a new art school.”22Led by philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs (widow of Apple founder Steve Jobs), the consortium includes Brenda Way, founder and artistic director of San Francisco’s Oberlin Dance Collective, and San Francisco Conservatory of Music President David Stull. Jobs would provide the preliminary endowment to buy the property and fund the new organization.

The same article reported that Supervisor Peskin “quietly introduced an ordinance that would create a special use district” that would allow an unaccredited educational institution to operate on the site of SFAI.

SFAI Board President Graham commented, “This was the hope—that the school wouldn’t turn into condominiums, that it wouldn’t be acquired by some commercial concern or knocked down, that an educational institution would be installed and, in some form or another, carry on the legacy. Right now, we don’t really know what they intend to do.”

Californian School of Fine Arts fresco class, undated, San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

In December, the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in San Francisco ruled that the sale of SFAI’s assets to the consortium was allowed to move forward.23The purchase price of $30 million included the buildings, land, library, the undeveloped meadow adjoining the school, the archive, and the Diego Rivera mural. The mural, previously appraised at $50 million, was cited as “the mural and related property” which were valued at $7.5 million.24

Laurene Powell Jobs and the consortium were the only entity to make a serious offer for the

property. In a document filed with the court, the bankruptcy trustee noted that he failed in his attempts to find other buyers for the school or the mural. He believes that the multiple landmark designations discouraged them.25

To date, the consortium has not released any further information about its plans for the school or the SFAI campus.

“The question, which is unanswerable,” said Marx, “is what if Laurene Powell Jobs and the group had come to us before the closure and offered to buy the school?”

Although there has been no formal confirmation as to whether the archive can retain its independent status, the archivists take a positive view. After the September announcement, representatives of the consortium visited the archive at its present site. Archivist Gunderson described them as “enthused, supportive, and interested in SFAI’s history.”

Renovations to SFAI’s building, estimated at $50 million, will be a lengthy process. The archivists imagine remaining at their current location for the time being and returning to the Chestnut Street site when it is completed.

“Regardless of what happens down the line with this new entity, the consortium expressed interest in the archive eventually moving back to the building, which is right from my perspective,” said Alexander. Gunderson added, “The material belongs there, and we could remain independent at that site. The archives are key to the legacy of the place, and the focus of everybody’s attachment to it. Alumni and others will be able to walk into that building and see the remnants of the San Francisco Art Institute.”

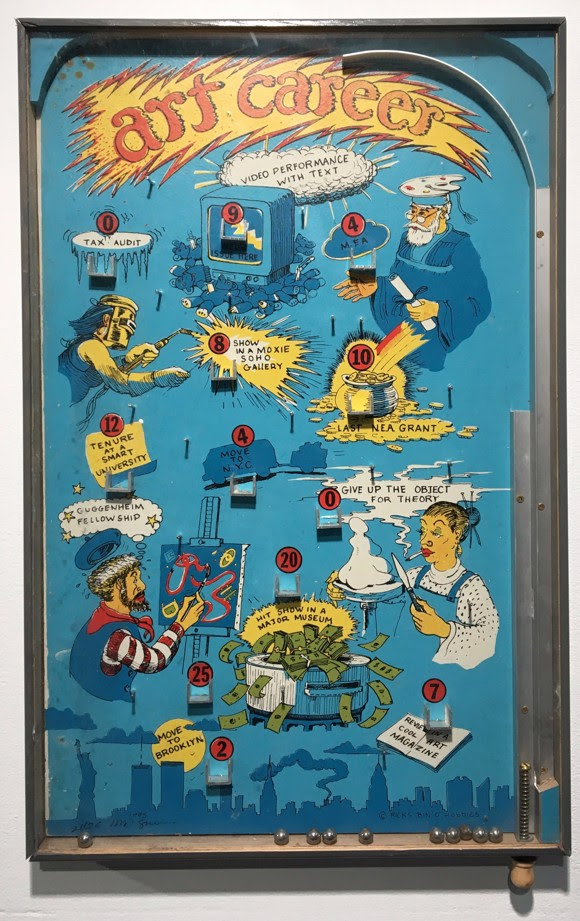

Richard Shaw, SFAI faculty, Art Careers Pinball, mixed media, 1995. Courtesy of the artist.

At the Inflection Point

The last few years have been devastating to independent fine art colleges. On January 12 of this year, the oldest art school in the United States, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, announced that it will end its degree programs after the 2024-2025 school year. It joins a growing number of fine arts colleges that have closed or merged with larger institutions.

“In a world that is seeing increased attacks on higher education, liberal thinking, critical thinking, I think we were so special,” says Rissler. “What has been lost? It’s the ethos of experimentation, a safe haven for dialogue, debate, and critique; the championing of the conceptual mindset particular to artists and seeing how it can create the unimaginable.”

As Executive Director of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design, Deborah Obalil has overseen the recent demise of member institutions. “Fine arts education is at an inflection point,” she said. “Historically, it wasn’t always part of academia, and some would question whether it should be. At this point, given the costs, it may be a mismatch for fine arts education to function within institutional academia.”

Fred Olmsted Jr., Marble Workers, fresco, circa 1935, restored by Molly Lambert with a “Save America’s Treasures” grant from the National Park Service and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.

Beginning Again

SFAI’s dispersed community has entered a new phase as a culture in exile with the archive and the alumni association often acting as springboards for creative projects. “The brick-and-mortar campus is gone,” said Rissler, “but the legacy of SFAI’s type of teaching and artistic practice will be continued by those who were there, through teaching, mentoring, or any line of work they might find themselves in.”

“We’re existing in a different way now,” said alumnus Lexygius Sanchez Calip. “SFAI is still here. It didn’t go anywhere. It just transformed, like the fog–our school mascot.”

In 2023, 12710 in Berkeley presented “Dude, Where’s My School?”26The exhibition featured a group of faculty and students who attended SFAI in its final years. Curator and SFAI alumnus Josh Hash refers to the artists in the exhibition as “No School.” He likens them to cohorts like the Young British Artists in the late 1980s, or Los Angeles’ Cool School artists of the 1960s. “It is a pivotal moment,” he says “when No School artists are tasked with governing their own networks, infrastructure, and legacy.”

“When there’s no roadmap, how do we carry on?” said Eve Werner who was among the last cohort of students to receive MFA degrees from SFAI. She was the lead coordinator on the current exhibition IN-FLUX: recalibrating the unknown, curated by former SFAI painting instructor Jeremy P. H. Morgan. Featuring the work of artists associated with the school, the exhibition uses the fall of SFAI as a catalyst to explore “possibilities within the current dynamic fusion of social, environmental, economic, and epidemiological challenges.” Presented by SFAI’s alumni association and featuring more than 170 artists, IN-FLUX opened on March 21 at The Museum of Northern California Art in Chico.

“It’s not just the loss of the school,” said Barbist discussing the exhibition. “Our alumni have dealt with many of the extraordinary situations that we’ve all experienced over the last few years. “We have an alum who’s making work based on the fires in Northern California. Alumni in Greece have confronted wildfires there.”

“Everywhere you look, change is happening,” said Werner. “We’re exploring how to deal with that.”

The sale of SFAI to the nonprofit led by Laurene Powell Job closed on February 29. In the meantime, SFAI’s artists and scholars are creating a new decentralized paradigm for arts education and community. What will transpire in the coming months and years—the fate of SFAI’s independent archive, and the projects of the school’s free-floating yet interconnected culture—will offer models for evolving beyond the chaos of shattered institutions to meet the aspirations of our current moment.

Attendance as recorded by Bruce Conner for his Fall 1967 “Life Drawing II” class. Courtesy of the San Francisco Art Institute Legacy Foundation + Archive.