Universal Steel: Mark di Suvero, Occupy Wall Street, and the Artists’ Tower of Protest

by Travis Diehl

Mark di Suvero’s Joie de Vivre in an empty Zuccotti Park, after the eviction of the Occupy Wall Street protesters, December 2011. Photo: Trevor Patt.

Let us imagine a newspaper where on facing pages the two opposing views are given on one subject—without an editorialized conclusion: Wouldn’t that cause some thinking rather than the ghost emotional basis of political belief?

—Mark di Suvero, Dreambook1

On October 2, 2011, members of Occupy Wall Street in Los Angeles were settling in for their second night on the lawn of City Hall. As Rirkrit Tiravanija and Arto Lindsay rolled toward MOCA at the head of a column of local artists—their so-called Trespass Parade—a group of Occupiers joined the floats and dancers, waving signs and leading their signature chant: “We are the 99 percent.” It was opening weekend of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time initiative—a sprawling program that thrust the history of Southern California art into the canon—with the support of dozens of local institutions and the corporate partnership of Bank of America. Included in the lineup of massive museum surveys and performance festivals was Mark di Suvero’s The Artists’ Tower of Protest, better known as the Peace Tower—a re-creation of the sculpture di Suvero made in Los Angeles in 1966 to protest the Vietnam War, dusted off again after its installation by Tiravanija at the 2006 Whitney Biennial. Zuccotti Park would be power-washed clean and City Hall’s lawn emptied and fenced off weeks before this third Peace Tower would be built and quietly hung with paintings in January 2012.

Riot squads moved to clear the Occupy Wall Street camp at Zuccotti Park in the predawn of November 15. It was by the book. Officers edged in; resisters were arrested. As unremarkable as this deliberate drama was its setting: a good example of the ubiquitous privately owned public plaza, complete with a monumental yet innocuous sculpture.2In the shaky lo-fi video that streamed from laptops and smartphones, three cherry-red I-beams slashed down toward the floodlit granite, gray-green trees, growing mound of tents, and NYPD blue: the girders of Mark di Suvero’s 1997 Joie de Vivre.3 It’s more than a coincidence that this modernist giant and all those motley demonstrators wound up staking out the same bleak corporate plaza. Indeed, when Occupiers overtook the park in front of the Bank of America tower in Los Angeles, the ensuing LAPD action played out under and around the sweeping orange-red steel of Alexander Calder’s Four Arches (1975).4

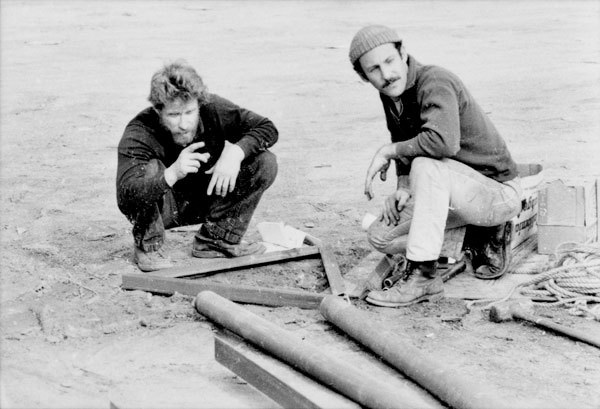

Mark di Suvero (left) and Lloyd Hamrol working on the Artists’ Tower of Protest (Peace Tower), Los Angeles, 1966. Charles Brittin Archive, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (2005.M.11). Photo: Charles Brittin. © J. Paul Getty Trust.

It would be easy enough to dismiss Di Suvero as complicit with banks and multinationals or at least irrelevant to the Occupy movement. Yet as art-savvy Occupiers have noted, the interlocked tripods of what the Occupied Wall Street Journal once called the “weird red thing” echo, albeit in a mature modernist idiom, the tubular scaffolding of the sculptor’s Tower of Protest.5 “I had been painting stick figures: war victims,” Di Suvero said of his one year in the philosophy program at UC Santa Barbara—abstract figurations presaging the ecstatic, limblike hourglass of Joie.6 Di Suvero transferred to Berkeley in 1955 and finished his degree, but he was already a dedicated sculptor; in 1957, he moved to New York. In 1965, Irving Petlin and the Los Angeles–based Artists’ Protest Committee approached Di Suvero with a proposal to mount a demonstration against the war in Vietnam.

The Artists’ Tower of Protest, informally known as the Peace Tower, was the result: an abstracted peace sign rendered in jointed steel pipes, erected on an empty lot below a Hollywood hillside. The 50-foot structure was designed to support hundreds of 2-foot-by-2-foot anti-war paintings donated by the likes of Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Frank Stella. In the charged political climate of mid-sixties Los Angeles, where even Abstract Expressionists were radicals, the tower was a lightning rod. Rallies at the Peace Tower drew everyone from Susan Sontag to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters to then-editor of Artforum Philip Leider.7 Nightly harassment by pro-war demonstrators and angry Marines from a nearby base interfered with construction and left one artist badly beaten. Although no artworks were damaged (Petlin famously defended the Stella with a broken lightbulb), the 418 panels could not be hung as planned and instead braced a fence around the sculpture. Three months into the protest, the owner of the lot refused to extend the lease; the tower was dismantled, and the paintings were auctioned off to finance the committee’s next engagement.

Mark di Suvero, Artists’ Tower of Protest (Peace Tower), 1966. Steel and mixed media, 55 ft. Installed Los Angeles. Charles Brittin Archive, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (2005.M.11). Photo: Charles Brittin. © J. Paul Getty Trust.

Di Suvero was arrested and jailed two times during anti-war demonstrations before he left the U.S. in 1971 for five years of self-imposed exile, and again in 2004 while protesting outside the Republican National Convention in New York, where he called George W. Bush a liar—perhaps why Di Suvero is the rare modernist sculptor still noted for his progressive, pro-union, leftist political leanings.8 It’s not unusual for an article on a recent retrospective to cite the Peace Tower as evidence that he has always been “an outspoken activist” or “a lifelong activist for peace and social justice.”9 New York art writer Jason Farago, noting the irony of Joie’s presence in Zuccotti Park, calls Di Suvero one of the “great artists of the American left” and describes the sculpture’s paint job as “a bright proletarian red.”10 Di Suvero is also a key member of the group of artists that turned a Long Island City dump into the Socrates Sculpture Park, which is both an official city park and a collectively organized, outdoor public art museum.11

Yet if Di Suvero’s personal convictions have weathered well, The Artists’ Tower of Protest remains his only public artwork made in explicit support of a political cause. His subsequent Flower Power (1967) and Mother Peace (1969–70), despite their tie-dyed titles, exhibit the signature red I-beams that have defined his sculpture ever since. Sibling works to Joie, produced from 1996 to 1997, have ebullient, humanist names like E=MC2, Galileo, and Pour le Poéte Inconnu.12 The anti-war stance that found expression at the Peace Tower has been reconstituted as a quaint, hippyish aura—associated less with protest, more with the hard-edged safety of the well-surveilled corporate park. Di Suvero and his generation of artist-activists now represent not the petty squabbles of topical politics, rash cycles of revolt and crackdown, but a cosmic spirituality; an overarching, human, modernist concern; and the inert pacifism of steel that, for what it’s worth, became a sculpture and not a battleship.

Mark di Suvero, Mother Peace, 1969-70. Painted steel, 42 ft. Installation view at Crissy Field, San Francisco, 2014. Photo: Matty Gilreath.

In September of 2001, wreckage from the nearby World Trade Center covered what was then known as Liberty Plaza. Brookfield Office Properties renovated the site in 2006, installed Joie, and on June 1 rechristened the park after company chairman John Zuccotti. Di Suvero was present at the opening ceremony, but, according to the artist, was barred from speaking due to his recent criticism of the Iraq War.13 Meanwhile, uptown at the Whitney Museum of Art, another Di Suvero had just been dismantled: Rirkrit Tiravanija’s redux of Di Suvero’s Peace Tower. This second version had its genesis in the anti-war protests of early 2003. The project found little traction at the time (plans to build a tower in Central Park during the 2004 Republican National Convention were scrapped), but in 2006, Tiravanija, with Di Suvero and Petlin’s help, produced a new tower for the Whitney Biennial. The updated scaffold, bearing paintings by a handful of original Peace Tower artists as well as dozens who had contributed to the 2003 Utopia Station (curated by Tiravanija along with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Molly Nesbit), rose from the museum’s sunken sculpture court up to street level beside the entrance—an emblem of the renewed yet nostalgic political zeal that characterized the exhibition as a whole.

Against the backdrop of two wars, natural disaster, and genocide, a sense of history in process united the “radical heterogeneity” of practices collected for the biennial. The Whitney’s director, Adam D. Weinberg, summed up the national moment as one of psychic paradox, while the central catalog essay by Toni Burlap [a fictional third curator invented by Biennial co-curators Chrissie Iles and Philippe Vergne] described contemporary art as “a working through of the endgame of the tired models of modernism.”14Indeed, in addition to the Peace Tower, the show included the late output of canonical modernist Richard Serra, who exhibited a painting based on an iconic photo of tortured prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Tiravanija and company, while calling attention to history, performed an even more emphatic inscription of their current moment into that same history. The idea of the Tower became swept up in the Whitney’s rhetoric to the point where Burlap wrote “it may not be an exaggeration” to say that the 2006 Tower is the most audacious public display by a museum of a “large-scale political artwork, made spontaneously in reaction to war” since 1939, when MoMA saved Guernica from the fascists.15 Yet 2006 was not 1966. There was no vandalism at the Whitney site, no pro-war demonstrators, and no Vietnam—only a full-blown military-industrial cancer to contend with, a radically heterogeneous globalized range of causes. Rather than a lighting rod, Peace Tower became a historical anchor; plucked from its original moment, Di Suvero’s sculpture was oddly gutted, lending the biennial a vague, even decorative idealism.16

Rikrit Tiravanija and Mark di Suvero, Peace Tower, 2006. Steel and mixed media. Installed at the Whitney Biennial. Photo: Sarah Glidden.

A negligible bump on the urban continuum, the 2006 Peace Tower nonetheless straddled the confluence of two trends: the privatization of public space and the privatization of the arts. Zoning and tax incentives first introduced in New York in the early 1960s, including popular percent-for-art laws, allowed developers to build higher—provided the building’s lot included a public park and so long as a portion of their project’s cost (usually 1 percent) went toward public art. Corporate plazas proliferated, and municipal governments subtly reallocated responsibility for new public space into private hands. As this trend accelerated in the 1980s, the Reagan administration mounted its assault on public arts funding, which hemorrhaged and dried up—especially for works deemed ugly, elitist, or otherwise anti-human. Artists and institutions came to rely on capricious and conditional private money. The enormous sculptures picked by corporations to fulfill their civic obligations have come to symbolize the lowest common denominator of safe taste. Meanwhile, the amorphous range of plutocrats, petrodictators, and multinationals that galvanized Occupy also fueled the economic boom behind parks like Zuccotti. The presence of Joie de Vivre on the Occupiers’ chosen ground illustrates the success of neoliberalism, even as the protesters embodied its failures.

The uproar leading to the destruction of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc (1981) is a key episode in the cowing of large-scale public sculpture. Serra’s piece had been commissioned by the General Services Administration (GSA) with public money and installed in the barren courtyard in front of the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in Foley Square, the civic center of New York City. In 1989, an “independent commission” led by William Diamond (regional administrator for the GSA) on behalf of the building’s employees demanded the sculpture’s removal, claiming, among other things, that the sweeping Cor-Ten steel form with its patina of rust gave cover to muggers, encouraged public urination, and would amplify a bomb blast. Arc’s proponents argued that the site-specific sculpture’s relocation would be a clear breach of Serra’s contract and a dangerous precedent for the suppression of free speech in favor of populist taste. In the show trial that followed, even defenders of the sculpture acknowledged it was a difficult (though important) artwork—such as critic Roberta Smith, who called it a “confrontational, aggressive piece in a confrontational, aggressive town […] Serra wanted a piece you could not ignore like a statue on a pedestal,” she testified. “It is not wide entertainment, and it is not an escape from reality, but it does ask you to examine its own reality.”17

Richard Serra, Tilted Arc, 1981. Steel, 12 ft. x 120 ft. x 2 1/2 in. Installed in New York City (destroyed 1989). Photo: David Aschkenas.

In both public art and public space, privatization has favored an innocuous but aloof product, accountable not to the citizen but to the consumer. By now, a project like the Peace Tower is less likely to be realized by an artist collective than by an institution like the Whitney or the Getty—which, for all their good works, are technically little different from any other quasi-public, privately held company with a sculpture in front of its headquarters. Even Socrates Sculpture Park—“the only site in the New York Metropolitan area specifically dedicated to providing artists with opportunities to create and exhibit large-scale sculpture […] that encourages strong interaction between artists, artworks and the public”—must supplement its backing from the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of its “generous and dedicated Board of Directors,” which Di Suvero chairs.18

By late 2011, the U.S. had ceased combat operations in Iraq, Osama bin Laden was dead, the financial “downturn” had dampened enthusiasm across the country, and Occupy Wall Street was on the march. Yet while his Joie de Vivre was a landmark on the Occupiers’ home turf, the often outspoken Di Suvero kept silent on the subject. Critics insinuated, none too subtly, that Di Suvero had deferred to his wife, Kate Levin, then–New York mayor Michael Bloomberg’s commissioner of cultural affairs—and indeed, pressure from his patrons in the establishment had prevented him from speaking at Zuccotti’s rededication. Meanwhile, Occupiers used Joie de Vivre to post signs or to bash corporate art.19One protester climbed the sculpture and demanded NYPD deliver cigarettes by cherry picker.20 Following this incident, the sculpture was fenced off, prompting the Occupy arts and culture working group to write Di Suvero an open letter:

Your sculpture, “Joie De Vivre,” at Liberty Plaza (“Zuccotti Park”) has served as a visual backdrop for the movement in New York. The area underneath and around the sculpture has hosted meetings, rendezvous points, teach-ins and concerts. We are conscious of your role in the creation of the Peace Tower (1966 and 2006), and your public opposition to the wars in Vietnam and Iraq. Your work is an integral part of our collective history, and the tradition of artists who exercise their responsibility as public citizens.21

The working group invited Di Suvero to the camp—to speak out against the barricading of his “gift to the city” and to share his views. By this point, a few art writers had also made the connection, pointing out Occupy and Di Suvero’s common sympathies. Greg Allen of Greg.org, for one, told Occupiers to team up with the Di Suvero of Peace Tower fame and deck Joie de Vivre in protest paintings.22 Yet the sculptor did not respond. After all, Joie was Di Suvero’s “gift” in an abstract sense only: It was MoMA president Agnes Gund who had given the sculpture to the City of New York, where it spent several years on the Holland Tunnel rotary before being moved to Zuccotti and becoming property of the Brookfield Charitable Foundation. Further, when it came to Occupy, Di Suvero’s absence was in keeping with his long view of history—an engagement with politics in many ways as large-scale and abstract as his art.

Occupy Wall Street protester perched in Joie de Vivre, October 2011. Photo: Kevin Hagen.

Di Suvero’s Dreambook, published in 2008, is a catalog pairing photos of his sculptures with short texts and poems—a mixture of quotes and the sculptor’s own writing meant to “reanimate” the “flattened” steel. Di Suvero offers his views on religion, science, math, philosophy, and politics (though his views on art remain expounded only in relief—that is, by express omission). Several passages resonate with Occupy, such as the one facing 1982’s Shoshone: “The representative form of democracy is not true democracy but a reflection of the aristocracy’s distrust of the masses. When much power is given to a few, only fools say the few will not profit from it.”23 Then again, this aphoristic wisdom is general enough (ahistorical enough, even) to apply to almost any uprising. Indeed, in his essay “Mark di Suvero, or The Era of Builders,” Francois Barré glosses Di Suvero’s stance toward both artistic and political movements, preempting the sculptor’s silence regarding Occupy. “Di Suvero has a progressive view of history,” he writes, “refusing to be a part of any movement or trend, preferring to locate himself within the dense power of the city and its workspaces.” Barré goes on to note that Di Suvero’s studios are “situated on industrial sites […] among buildings on the fringes of the city.”24If his sculptures are often at the heart of the action, in public, in parks like Zuccotti, the artist aligns himself not with the daily life or sectarian politics of the city but with the forces behind its construction.

Dreambook portrays a Di Suvero invested in a gradual, transhistorical improvement of the human condition. At first glance, Occupy presented a similarly broad view—one informed by the essentially progressive concerns of the antiglobalization movement. But on the ground, Occupy attacked the particulars of globalized power from a wide array of political perspectives, further entangling these indictments in a fantastic display of daily survival. If “anti-war” was a cause so plainly (yet so abstractly) addressed to evil as to earn Di Suvero’s vocal support, here the abstract, globalized mechanisms underlying “war” became implicated in an overwhelming number of specific cases: foreclosures, bank fraud, job discrimination, surveillance, drone strikes, torture. Occupy’s aesthetic dimension was no more resolved and just as specialized. A wide gulf separated the reactionary style of Adbusters, the Canadian magazine whose Twitter feed kicked off the occupation, from the rational activism of Judith Butler, one of its most eloquent advocates. The arts and culture working group initially separated its daily agenda into “arts” and “culture.”25 Di Suvero’s towering Joie served as a rallying point, while the relentless OWS drum circle became a public symbol of the movement.26 Yet this confusion nonetheless mapped the contours of a confusing political moment—or, as Slavoj Žižek put it, gave us “red ink” to write with—naming the limits of our liberties, such as the very real restrictions on our civic parks and sculpture.27 In the same way, Di Suvero’s brush with Occupy gave us “red steel”—a symbol of one movement’s transmutation into an alien, anarchic time.

The Los Angeles and New York Occupy camps were both uprooted in November 2011, several weeks before the third Peace Tower was erected on a vacant Hollywood lot in January 2012.28 This time, drowned out by the self-promotional static of Pacific Standard Time, there was no fanfare for the Tower, no Tiravanija, no Artforum cover, and very little press. Enough people responded to an open call for contributions that dozens of small square artworks overflowed onto the fences surrounding the property—yet this same fence kept visitors at a safe distance from the scaffold and made the slogans and pictures hard to read. Despite fresh and topical images (one painting featured a bleeding Bank of America logo), the tower was more of a relic than ever—indeed, in the context of PST, explicitly so. Compared with the clamor surrounding the 2006 incarnation and the 1966 original, the third tower’s inertia seemed to reflect the weariness of artists and institutions toward this aging model of activist art—even a post-Occupy exhaustion.29

Four women looking at art work at the The Artists’ Tower of Protest, 1966. Charles Brittin Archive, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (2005.M.11). Photo: Charles Brittin. © J. Paul Getty Trust.

“High capital has already absorbed one generation of protesters into its logic,” wrote Jason Farago in the early days of Occupy, “and this one probably won’t fare much better.”30 Yet it’s too easy to retreat into cynicism about Di Suvero and his humanistic steel gestures, or to fault one generation of protesters’ failure to learn the lessons of the last. Nor should we expect the Di Suvero Peace Tower to carry more than a nostalgic message in an America almost five decades older, just as the Di Suvero of 2012 is an anachronistic model for an artist-activist. Di Suvero told Artforum in 2006, caught in the fervor of the biennial, that he believed “the ability to think abstractly naturally led one to refuse the reactionary attitudes that were so prevalent” in the 1960s.31 But abstraction isn’t the radical gesture it was at mid-century. Far from it: Globalized capital is nothing if not abstract; the overarching, despecified, cosmic flow of capital is certainly someone’s idea of progress. Thus, Di Suvero’s sculpture has moved into the commodified future.32 Occupy, with its jumble of nostalgia, Web 2.0 tactics, and frenetic specificity, is regrouping in the margins of history, while the police, and the plutocrats who called 911 on the protestors, revise their tactics with military regularity and with a tenacity best described as creative.

“I try to make people feel their own capacity to move these masses,” said Di Suvero in a 1985 interview—speaking of his kinetic sculptures but echoing his politics. “Of course, I want it to be safe and controlled. I’m not in favor of limits, but they do exist.”33