Vision Magazine: Idea-Oriented Art in Print (1975–1981)

by Tom Marioni

Artist Tom Marioni is best known for early Conceptual works such as The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends Is the Highest Form of Art (1970), and as the founder of the Museum of Conceptual Art (MOCA), one of the first alternative art spaces in the United States, which he opened in 1970 and directed until its closure in 1984. He published the first issue of Vision, an extraordinary publication which lasted for only six issues, in 1975. Both MOCA and Vision helped to define new forms of art making and connect artists experimenting in a site-specific or performative vein. Here, Marioni recounts the story of Vision 36 years later.

Vision’s purpose, I wrote in 1975, was to present “works and material only from artists” and “to make available information about idea-oriented art.” I was the editor-designer and the publisher was Kathan Brown, owner of Crown Point Press, the etching workshop in San Francisco. Over the next six years we produced five issues, the first three of which functioned somewhat like exhibition catalogs with an introduction by me followed by individual artist-designed pages, and a page of original art (not a reproduction). Although the Swiss magazine Der Lowe and the Conceptual art magazine Avalanche inspired me, I had a different approach: I wanted to make Vision an extension of MOCA, my Museum of Conceptual Art that I had founded in San Francisco in 1970. Originally my idea was to focus each issue on a different region of the world, and I thought of the magazine as a kind of exhibition in a publication.

The first three issues, “California,” “Eastern Europe,” and “New York,” follow that form. For these issues, the publication in its proportions was close to a golden rectangle, so two facing pages created almost a square. I was a contemporary of most of the artists in the California and New York issues, and I was also a curator, so I knew all the artists. For the “California” issue I wrote a letter explaining the assignment, and everyone was willing to give me material. I visited the New York artists and explained what I was looking for, and they sent the material on later.

In the introduction to the first issue of Vision I wrote, “New York is still a center, but for the first time since the Renaissance there are many centers. Artists around the country and around the world are finding their identities where they are.” I’ll say more later about the first issue, “California,” which was about the place where I was living (and still live). But first, a few words about the other issues.

Office of the Museum of Conceptual Art, 1975. Photo: Tom Marioni. Published in Vision, issue 1, 1975.

Vision no. 2, “Eastern Europe,” published in January 1976, was the first publication in the West on underground avant-garde artists (such as Tadeusz Kantor and Marina Abramovic) of the Soviet-ruled countries of Yugoslavia, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. The original art for this issue was a print from a hand-applied rubber stamp saying “Free Art Work” by Radomir Damjan. I traveled to Eastern Europe to meet the artists, most of whom I knew about from information they had sent in the mail to MOCA. I wrote that I would be coming, and they made arrangements for me, often putting me up in their homes. The ones I contacted introduced me to other artists.

Vision no. 3, “New York City,” came out in November 1976. Thirteen artists, including Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre, and Hans Haacke, created art about New York, and Walter De Maria produced an original work for the issue: eight pages of buff-colored paper with his name on the seventh page.

The last two issues of Vision were on themes rather than places, and were more like multiples than magazines. Vision no. 4, “Word of Mouth,” 1980, is a set of three LP records with talks by twelve artists: three from California including Chris Burden, two from Europe including Daniel Buren, and seven from New York including John Cage and Brice Marden. We recorded the talks at a meeting on the Micronesian island of Pohnpei in the Pacific Ocean. Kathan Brown and I conceived the conference as a way to produce an issue of Vision in neutral territory that encouraged social interaction and having fun. Crown Point Press paid for the artists’ travel, and I received a grant from the NEA to produce the records.

Vision no. 5, “Artists’ Photographs,” 1981, is a box containing loose-leaf pages of photographs by 76 painters and sculptors from sixteen countries. These are photographs as art, not pictures of art: conceptual photography instead of pictorial art. When Christo sent a photo of his Running Fence I asked him to exchange it for a photo as a work of art not of a work of art. He sent back a picture of himself with a bullhorn giving directions to workers.

The first issue of Vision, “California,” was the only one in the series with articles in addition to my introduction.1The cover photos were from an illustrated article by Kathan Brown on the Underground Gardens of Baldassare Forestiere, a folk-art masterpiece of one hundred underground rooms and landscaped patios, created in the 1920s in Fresno, California. I asked two New Yorkers, Claes Oldenburg and Vito Acconci, to write about California. Oldenburg had just completed a series of etchings at Crown Point Press, and Acconci had recently had his first show in California at MOCA.

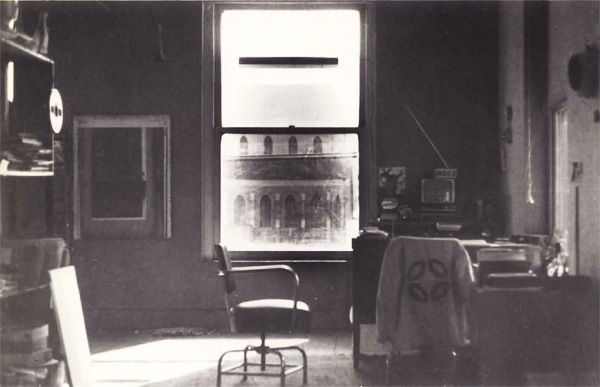

Bruce Conner, Sound of Two Hand Angel, 1974. Published in Vision, issue 1, 1975.

Oldenburg lived in San Francisco for a year in the fifties, and in LA in the sixties for about a year, and off-and-on later. He wrote of traveling “as if the whole country is a studio,” of going someplace to work with “a dealer, a print shop, a fabricator. You know that you will be welcomed, something will come out of it.” Oldenburg talked about the light in San Francisco, “the silvers in the evening from the mist and the changes in space that result from the atmosphere.” He saw Los Angeles as having “the glow that times past seem to have. The prevalence of art deco contributes to that, and the actual time difference of three hours, which furthers the isolation from the East. And then there’s the realization that you are actually in the place that is always shown on TV.”

“I have to widen my territory…,” Acconci wrote. “Pick up a show here … pick up a show there … keep myself busy … have to find a place for myself, that’s all … what to do, where to go.” At the end of his article, he had “seen the future, and its name is … its name is let me see now, its name is … Los Angeles!” He characterized Los Angeles as the Doors, and San Francisco as Jefferson Airplane.

Vision no. 1, “California,” featured artist-designed pages by 12 artists from San Francisco and 11 from Los Angeles. Not all the work in this issue was Conceptual. Wayne Thiebaud, a painter and a link between California and New York ideas, produced four figure drawings and a photo of himself talking to a female model in the studio.2In the majority of works from San Francisco artists, the figure is present in one form or another. The Bay Area figurative tradition from the fifties was carried into the seventies with Conceptual and performance art.

Bruce Conner reproduced his now famous life-size photograms of his body. Paul Kos showed photographs of his hands with rocks used to shape ice into a lens that the sun is shining through to create fire.3Jim Melchert made pencil rubbings of the backsides of photos, and in handwriting below them he described the figures in the photos. Linda Montano is shown in a photograph standing between her parents on the day she took the veil and joined a convent.4Other San Francisco artists included were Fred Martin, William T. Wiley, Terry Fox, Paul Cotton, Howard Fried, Bonnie Sherk, and myself.

In Los Angeles the art was unlike that of San Francisco because of the sunshine, the movie industry, and a glass and resin aesthetic. Several Los Angeles artists of the time were making temples of light. There was a bigger psychological distance between the two cities than most people thought. I still like to tell people from the East that California is four hundred miles south of San Francisco.

In 1975 in Los Angeles, Larry Bell was making large freestanding coated-glass “iceberg” sculptures with shadows. For his spread in Vision no. 1 he asked his wife, Janet Webb, to make illustrations of the two of them interacting with the sculptures.5Three artists used only text on their pages: Robert Irwin (“Twenty Questions”), Bruce Nauman (“False Silences”), and Ed Ruscha (“Bless You” printed three times). Michael Asher asked that his two pages be glued together, creating the original work in this issue. One can detect his participation either by looking in the table of contents or by noticing that page 42 is stiffer and thicker than the other pages. This was invisible conceptual art.

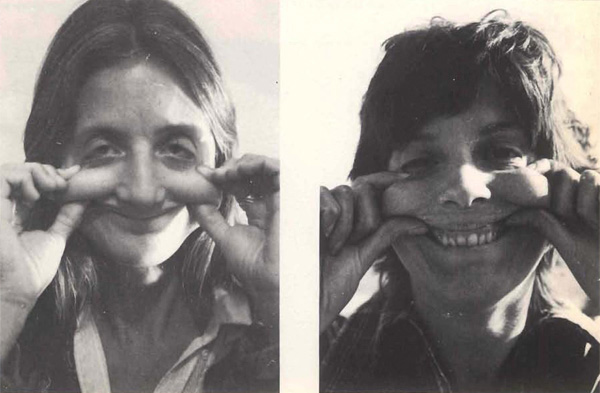

Detail from photo collage by Barbara T. Smith, published in Vision, issue 1, 1975.

Barbara T. Smith asked friends to make forced smiles using their fingers to create 15 Buddha faces demonstrating “varying degrees of proficiency and enlightenment.” Allen Ruppersberg’s two pages have two identical photos of a grove of trees. The one on the left reads “No sculpture here,” and the one on the right reads “here, or there.”

Other Los Angeles artists included were Robert Irwin, Doug Wheeler, Chris Burden, Eleanor Antin, and Charles Hill. For some reason I didn’t get work from James Turrell and I regret not asking John Baldessari.