Your Art Disgusts Me: Early Asco 1971-75

by Chon Noriega

California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) co-published Afterall from 2002-2009. This essay was originally published in Afterall 19, Autumn/Winter 2008. All original formatting has been preserved.

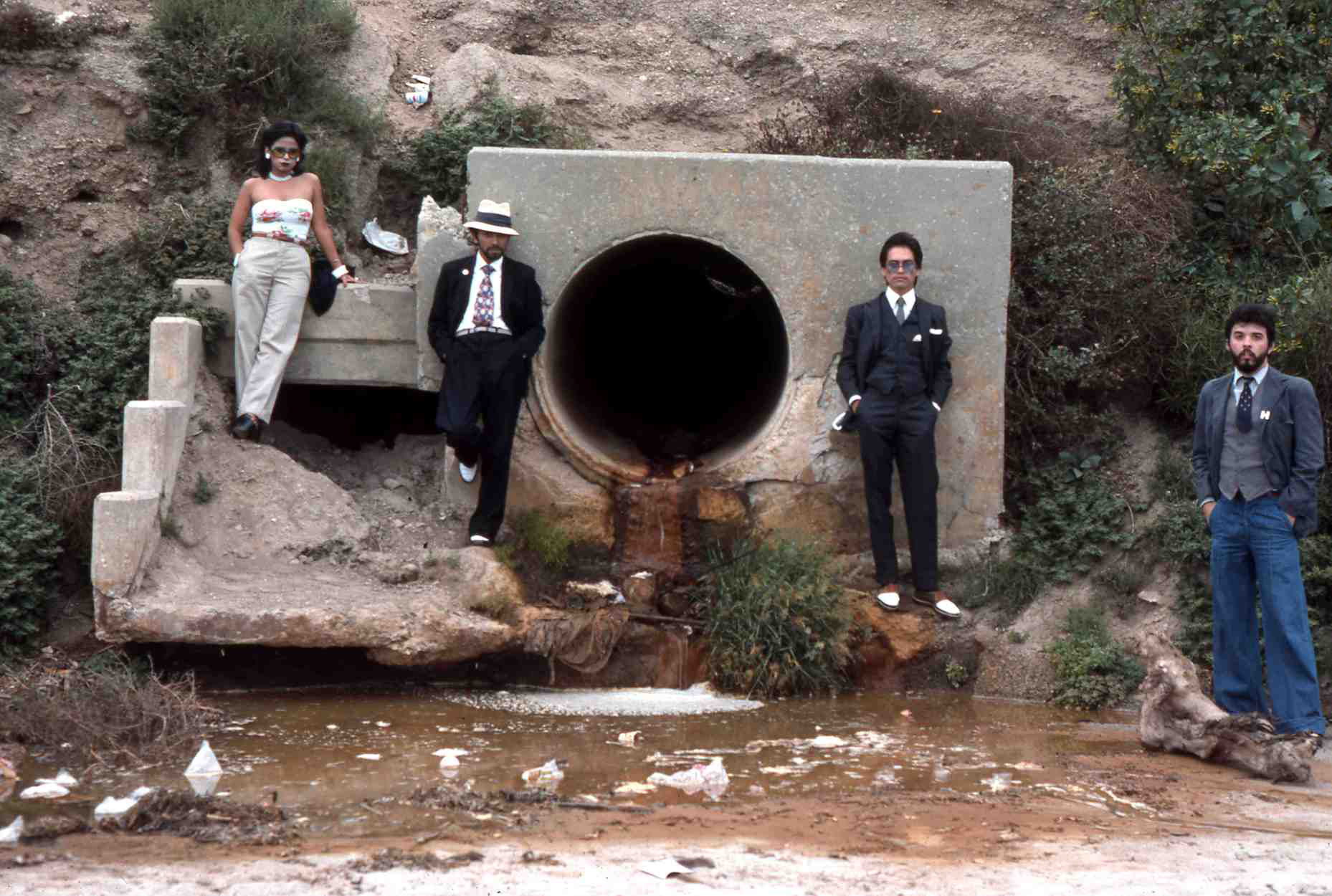

Asco, Asshole Mural, 1974. Colour photograph. Photograph: Harry Gamboa, Jr, showing Patssi Valdez, Humberto Sandoval, Willie Herrón III and Gronk.

In the late 1960s, four young Chicano artists in East Los Angeles began collaborating in various combinations, eventually forming an art collective and taking the name Asco — as in ‘me da asco’ or ‘it (your art) disgusts me’. One evening in 1972, three of its members — Harry Gamboa Jr, Gronk (aka Guglio Nicandro) and Willie Herrón III — signed their names to the entrance of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), claiming the public institution as their own private creation and thus making the world’s largest work of Chicano art in the affluent and white mid-Wilshire area of the city.1Spray Paint LACMA (1972), sometimes later referred to as Project Pie in De/Face, was conceived in response to a LACMA curator’s dismissive statement that Chicanos made graffiti not art, hence their absence from the gallery walls. In other words, ‘Chicano art’ was a categorical impossibility.

In signing the museum, Asco collapsed the space between graffiti and conceptual art, at once fulfilling the biased thinking that justified their exclusion and refiguring the entire museum as an art object itself, in accordance with the terms of institutional critique that were being developed at the time. Because the signed museum could not possibly fit within the museum gallery walls, it became the objective correlative for that categorical impossibility of Chicano art, the very condition that the institution helped to sustain. With Spray Paint LACMA, Asco made briefly visible the fact that the public mission of the institution — to be representative — was at odds with the aesthetic criteria that determined the curatorial agenda and thus what was installed on the interior walls. The artists understood that their gambit rested on the status the museum would give to their signatures, and whether they would be acknowledged as the signatures of individual artists authoring their work of art, or only as the illicit markings of an invisible social group of Chicano graffiti artists. When LACMA whitewashed Asco’s signatures, it simultaneously removed graffiti and destroyed the world’s largest work of Chicano art, obscuring the inclusive notion of the public that underwrote its existence.

LACMA, as the only major art museum in Los Angeles at the time and thus an arbiter of the emerging LA art scene, had been the object of an earlier critique in Ed Ruscha’s The Los Angeles County Museum on Fire (1965—68). The painting was started one year after LACMA opened and it was first exhibited at the Irving Blum Gallery in January 1968 with theatrical fanfare and staging. The invitation to the opening, sent as a Western Union telegram, announced: ‘Los Angeles Fire Marshall says he will attend. See the most controversial painting to be shown in Los Angeles in our time’.2The work itself was exhibited behind a protective velvet rope. Ruscha’s massive painting (it measured 136 by 339 centimetres) has been mostly read as ‘a metaphorical torching of artistic institutions and traditions’, but it did so at the precise moment that Ruscha and other artists associated with the Ferus Gallery were being welcomed into LACMA and other museums.3

Asco, Spray Paint LACMA, 1972. Colour photograph. Photograph: Harry Gamboa, Jr, showing Patssi Valdez.

This development can be traced back to the Edward Kienholz exhibition at LACMA in 1966, when Kienholz’s Back Seat Dodge ’38 (1964) became the object of considerable controversy over public funding for pornography and elicited reactions of disgust. These two Los Angeles artists helped set the aesthetic terms for the development of the city as an artistic centre, but did so through a prototypically West Coast interplay of media notoriety, commercial galleries and the art museum. If these artists challenged the museum as a cultural institution, Asco’s Spray Paint LACMA did so in terms of institutional racial exclusion.

Here it is useful to distinguish between the sense of preservation of the ‘public good’ that mobilised the censorship of Kienholz’s Back Seat Dodge ’38 on the one hand, and Asco’s demand to be recognised as artists from a constituent part of the museum’s public on the other. In the former, we see a power struggle over who gets to determine what is allowed for public exhibition: is it the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, who threatened to deny the museum’s funding unless the Kienholz work was removed since they deemed it to be pornography, not art; or is it the museum professionals, whose aesthetic judgment determined that Back Seat Dodge ’38 was art, not pornography (but also determined that Chicanos made graffiti, not art)? In this regard, censorship is not so much an assault on a transcendent ideal (‘art’) as it is an arena within which competing sectors of the professional/managerial class seek or maintain institutional control. The curators claimed expertise, while the supervisors held the purse strings. In the end a compromise was reached that not only maintained both claims, but also secured a public ‘space and voice’ for the LA white male artists associated with the Ferus Gallery: the sculpture would remain on display, but its car door would be closed, thereby obscuring the sex scene depicted inside. The door would, however, be opened upon the request of an adult viewer (only if there were no minors in the gallery). In the case of Asco, in which curatorial judgment is conceptually aligned with rather than juxtaposed to censorious notions of the ‘public good’, we see a détournement of this entire system. It is a détournement that exposes the underlying racial and class dynamics that exclude Chicano artists and that align curatorial judgment with graffiti abatement. Their focus is not on individual racism or the complicity between curators and supervisors, but on the larger system of organised practices that produce racialised subjects, part of what Michel Foucault calls governmentality or the ‘art of government’.

With the exception of Spray Paint LACMA, Asco turned its attention from the museum to the streets, from the art world to a community engaged in social protest. Its origins were activist rather than academic, and for good reason. In the 1960s, East Los Angeles high schools had the highest dropout rates in the nation, while Chicanos counted for a disproportionately high number of the casualties in Vietnam. In March 1968, some ten thousand students walked out of six East Los Angeles high schools, protesting racially biased policies and inadequate public education. For his role as an organiser of the walkouts, Gamboa — who ‘graduated’ from Garfield High School with a 1.1 grade point average — was identified as subversive in US Senate subcommittee hearings on the basis of the Internal Security Act. Speaking later about his time at Garfield High School, he recalls that ‘the environment there was so violent that it was almost like absurdist theatre…. I had seen instances where the police came on campus and beat the shit out of kids’.4

But if Garfield High School served as a necessary training ground for social protest, it also brought together a number of students who would later become prominent in music, visual art and performance. These students included the members of Asco as well as members of the musical groups Thee Midniters and Los Lobos, and notable performers Cyclona, Mundo Meza, and Humberto Sandoval. While in school, these future artists often took part in various ad hoc collectives and collaborations. In 1969, Gronk wrote Caca-Roaches Have No Friends, a play starring Cyclona, Mundo Meza and Patssi Valdez that was performed in Belvedere Park, where Cyclona’s violently homoerotic ‘cock scene’ stunned and enraged their Eastside Chicano family audience.5The mixture of impoverished educational environment, emerging student movement (with a strong arts and expressive culture component), police violence and biased media coverage gave a distinct ‘performative’ character to these self-identified teenage artists — their sense of art was defined not by genre per se, but by its ability to intervene productively within a contested social space.

The members of Asco first came together formally through the invitation of Gamboa, who asked them to work with him on the second volume of Regeneración, a political and literary journal published by veteran activist Francisca Flores and modelled on the radical journal of the same name published in the early 1900s by Mexican revolutionary Ricardo Flores Magón. Flores recruited Gamboa amidst the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War on 29 August 1970, when a police riot left several people dead, including Los Angeles Times reporter Ruben Salazar. As art historian Mario Ontiveros notes, ‘Regeneración provided the group an opportunity to examine publicly and critically “certain dogmatisms” at work in the political and art movement, as well as the dominant culture’.6In this regard, the future Asco members helped shift the editorial direction toward what Ontiveros calls ‘an intra-movement, self-reflexive analysis’ while they learned to work together in this critical mode through image and text aimed at multiple audiences.7The four artists quickly developed a unique visual style and conceptual approach that contrasted, and even ridiculed, the Mexican-inspired political iconography of the Chicano civil-rights movement (1965—75), while at the same time they were deeply engaged in that movement.

From 1971 to 1975, Asco’s guerilla-style street performances, often involving Humberto Sandoval as an erstwhile fifth member, intervened in a situation overdetermined by police violence, political surveillance, military recruitment and biased news media that structured and regulated social space in the Chicano community.8At the same time they challenged the Chicano movement’s nationalist political rhetoric, arguing that it promoted an orthodoxy and corresponding identity that failed to take into account the profound contradictions that actually shaped the lived experience of Chicanos — a group marked by cultural but not structural assimilation and, as a consequence, a group that was quite ‘American’ and yet excluded from or discriminated against by social institutions. Asco staged performances that both commented on and contributed to the mural movement (Walking Mural, 1972; Instant Mural, 1974; Asshole Mural, 1975) and the reclamation of Mexican-based cultural traditions (Día de los Muertos, 1974). During this time, Gronk and Herrón also painted murals that marked innovations in the use of expressive styles and conceptual frameworks, including their Black and White Mural (1973), which depicts the death of Ruben Salazar in relationship to Marcel Carné’s film Les Enfants du paradis (Children of Paradise, 1945) made during the Nazi occupation, as well as to Gronk’s performance persona Pontius Pilate (aka Popcorn), modelled in part after the film’s central character, a mime.9What one notices most about this body of work (including subsequent staged performances and conceptual video) is the unrelenting expression of violence outside melodramatic and moral discourses — as a cultural logic, an administrative tactic, a familial ritual and a fact of everyday life.

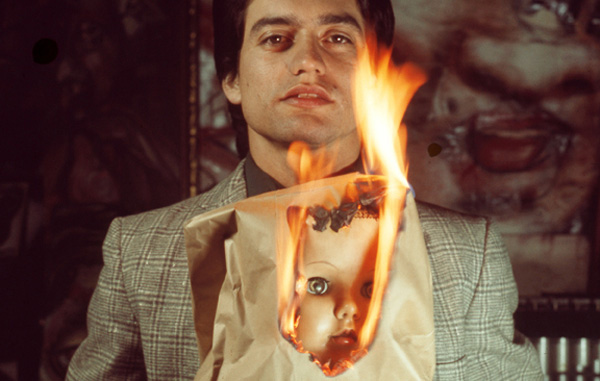

Harry Gamboa, Jr, Cruel, 1975. Super-8 film. Showing Willie Herrón III.

While Asco’s work engaged art-critical discourses and historical references, and increasingly sought to disrupt the mass media (in part by turning to the international press), in the first instance their work began as ‘an intra-movement, self reflexive analysis’ located within East Los Angeles. Indeed, Asco’s self-naming in Spanish, together with the predominant use of the English language in their artistic production, situates the group within both a linguistic community (the bilingual social space of East Los Angeles) and an interpretive community (a rights-based and nationalist ‘Chicano movement’ then at its height in the United States). If the phrase ‘me da asco’ marks unacceptable behaviour within a linguistic community of Mexican descent, the artists do not sidestep the admonishment by responding in English or by making countervailing aesthetic claims (‘But it’s art!’). Instead, they turn the admonishment into the start of a call and-response interaction that then produces a proper name. ‘Me da asco’ (literally, ‘to me it gives disgust’) produces a response that gives what has been called for: Asco. By naming themselves Asco, the artists refuse the notion that their work falls outside the norms or boundaries for the Mexicandescent community in East Los Angeles. Instead, they reinsert their art within the cultural logic of the community itself, defining their art in formal terms as those practices that self-consciously and critically engage the community’s use of language as a mechanism for self-regulation. If Asco upset traditional social norms for the Mexicandescent community, their work also challenged the more radical political agenda of the Chicano movement, where art played a central but largely illustrative role aimed at community mobilisation. And just as the use of a Spanish-language name located their project within that community, the use of ‘Asco’ as a proper name itself mirrored the self-designation ‘Chicano’, which had previously been a derogatory term within that same community. In both cases, Asco figured its challenge as endogenous, located not within a sense of an authentic or autochthonous culture, but as a troubling presence within the very linguistic and discursive strategies that culture (or social movement) used to define itself as such. In that sense, Asco’s approach — more in terms of style than method — was ‘deconstructive’ in the years before the term itself was introduced into English.

In 1975 Asco’s work appeared in several exhibitions, including ‘Chicanismo en el arte’, a juried selection of young artists at LACMA, organised in cooperation with East Los Angeles College. Asco also had a solo exhibition, ‘Ascozilla’, at California State University in Los Angeles and a joint exhibition, ‘Asco/Los Four’, at the Point Gallery in Santa Monica. That year is often cited as marking the end of the Chicano movement as a social protest movement. ‘By the end of 1975,’ according to Gamboa, ‘Asco had stopped functioning as a mutually supportive core group of four or five artists.’10Over the next decade, the four original artists developed individual careers and engaged in project-specific collaborations, while also contributing to the Eastside punk scene (Herrón not only fronted the band Los Illegals, but also ran the influential Club Vex) and to the development of alternative art spaces (Asco members were among the co-founders of Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, or LACE, in 1978) and the emerging arts and performance scene at gay bars (including Teddy Sandoval’s Butch Gardens School of Fine Art). Asco also served as a platform for staged live performance, conceptual video on cable-access television and art exhibitions that involved a new generation of artists, including Barbara Carrasco, Sean Carrillo, Diane Gamboa, Juan Garza, Daniel J. Martinez and Marisela Norte. During this later period, from 1976 to 1987, the expanded Asco became more explicitly engaged with the art world, often through interviews, mail art and performance pieces that staged ludic yet incisive debates with the arts establishment. Through Gamboa’s extensive photo documentation, Asco began to circulate its own history-cum-mythology, while using the trappings of celebrity culture in order to insinuate itself into the mass media. Their signature genre became known as the ‘No Movie’, and consisted of film stills for nonexistent movies, image-text pieces, mail art and media hoaxes. As Gamboa explains, ‘They were designed to create an impression of factuality, giving the viewer information without any of the footnotes’.11Or, as Gronk notes, ‘It is projecting the real by rejecting the reel’.12Central to this attempt to project the ‘real’ was a political investment in form itself. In this way, the No Movies share affinities with media historian Sheldon Renan’s notion of ‘expanded cinema’, wherein ‘the effect of film may be produced without the use of film at all’.13But in contrast to expanded cinema, Asco was not after the mere ‘effect’ of cinema, but rather putting forth a conceptual critique of minorities’ limited access to the capital, technology and social networks required to participate in the mass media. As Gamboa explains, ‘It was sort of like a political protest based on the economics of financing films, and also based on the reality that maybe I only did have five dollars’.14

In an article on Los Angeles avant-garde film, David E. James argues that ‘the No Movies both precede and exceed Cindy Sherman’s Film Stills’, drawing a sharp contrast between what he sees as Asco’s ‘critical distance’ and ‘communal opposition’ and Sherman’s ‘sentimental nostalgia’ and ‘individual narcissis[m]’.15While James offers a useful contrast, one that puts new artworks into play with older concerns about art and its relation to ‘the political system that comes into focus as “Hollywood”’, I question his emphasis on the ‘communal’ versus the ‘individual’ — especially insofar as Asco was always skeptical about notions of identity and community. I would argue instead that Asco and Sherman engage very different modes of oppositionality, particularly in terms of their exhibition and dissemination, and that those differences correspond with the critical reception, canonical status and market value of their respective works. At the same time, however, both Asco and Sherman proceed from marked categories, working within and against the restrictive representation of both women and minorities in Hollywood. The distinction to be drawn here between the No Movies and the Untitled Film Stills (1977—80) has to do with the discursive contexts for their oppositionality. As art historian C. Ondine Chavoya argues in ‘Pseudographic Cinema: Asco’s No Movies’: ‘Insofar as Sherman’s Film Stills are a simulation of overdetermined signifiers, the No Movie is a simulacrum for which there is no original.’16In other words, the Film Stills are staged against the backdrop of a long history of representation, and the No Movies against a history of invisibility.

Writing ten years ago, I raised the issue of the necessity and difficulty of locating Asco within historiographical frameworks of the Chicano movement and the post-1968 avant-garde, especially insofar as these were seen as antithetical projects (which Asco defiantly straddled). I posed two questions with the same answer:

What does the avant-garde look and sound like when it blooms outside the hothouse of the bourgeoisie? What does social protest against racism look and sound like when articulated outside a realist code? For a Chicano workingclass avant-garde group raised in the barrio, assimilated to American mass culture and making discourse the object of its social protest, the answer is simple: it looks like both and neither; and it sounds the same, but different.17

For its part, Asco theorised its own position vis-à-vis the mainstream and the art world, identifying itself with such terms as ‘the orphans of modernism’, ‘urban exiles’ and ‘celebrities of a phantom culture’. From the start, they were self-made fashionistas, a triumph of style over subsistence, staging countless celebrity shots for which, unlike Andy Warhol’s Superstars or Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, there were neither referents in the culture industry nor a marketplace in the art world.

In 2008, LACMA and its curators developed the museum’s first ‘homegrown’ exhibition of Chicano art, ‘Phantom Sightings: Art after the Chicano Movement’.18While the exhibition featured a younger generation of artists from around the United States working in a conceptual vein, and focused in particular on interventions within urban spaces, the first artwork that one encountered upon entering the exhibition was Spray Paint LACMA. Other photographic and Super-8 works in the exhibition documented Asco’s street performances, media interventions, conceptual cinema (No Movies) and performance murals, while also gesturing toward a broader milieu of self-created celebrity, costume design, performance and music in East Los Angeles in the 1970s. These early works by Asco acknowledge the group’s influence on Chicano conceptual artists who came of age in the 1990s, while also providing a historical framework for Chicano art vis-à-vis the history of the North American avant-garde.

Asco, Walking Mural, 1972. Colour photograph. Photograph: Harry Gamboa, Jr, showing Patssi Valdez, Willie Herrón III and Gronk.

Asco has influenced or provided a point of reference for a new generation of artists and artist groups whose work explores similar issues within public space, including the groups Slanguage (Mario Ybarra, Jr and Juan Capistran) and The Pocho Research Society of Erased and Invisible History (Sandra de la Loza), as well as individual artists such as Arturo Ernesto Romo and Ruben Ochoa.19However, while recent work by these younger artists has a genealogical relationship to Asco (and the Chicano movement), its sociohistorical context is radically different. Since the 1990s, the social reform programs that responded to the broader protests of the 1960s and early 1970s have been largely dismantled. Meanwhile, the Latino population has grown from a small minority to, now, a plurality or even a majority in many urban centres, albeit as an increasingly diversified and stratified group. Finally, the cultural landscape is now one defined by global mass media and ‘new technologies’ (a phrase that already sounds quaint), often at the expense of public support for both elite and community-based arts. In short, this new generation operates outside of both a social movement and a viable notion of the public (both of which provided necessary frameworks for Asco’s Spray Paint LACMA) and it does so within the intensified ‘white noise’ of global media and a multiracial, multilinguistic urban street culture. To be sure, much has changed, but then again much has not, which explains Asco’s continuing relevance nearly four decades later. Indeed, Chicano art is still absent from mainstream museums in the United States, and in East Los Angeles the high schools continue to have the same extraordinarily high drop-out rates as they did in the 1960s, for which one is inclined to say ‘me da asco’.